- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What image does the word orphanage conjure up in your mind? A sunny scene of carefree children at play in the grounds of a large ivy-clad house? Or a forbidding grey edifice whose cowering inmates were ruled over with a rod of iron by a stern, starched matron? In Children's Homes, Peter Higginbotham explores the history of the institutions in Britain that were used as a substitute for childrens natural homes. From the Tudor times to the present day, this fascinating book answers questions such as: Who founded and ran all these institutions? Who paid for them? Where have they all gone? And what was life like for their inmates? Illustrated throughout, Children's Homes provides an essential, previously overlooked, account of the history of these British institutions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Early Children’s Homes

Christ’s Hospital

A strong claim to being England’s first institutional home for poor or orphan children can be made by Christ’s Hospital, which was situated on London’s Newgate Street, a couple of hundred yards to the north of St Paul’s Cathedral. The building, formerly the Greyfriars monastery, was a victim of Henry VIII’s dissolution of England’s religious houses. Henry subsequently made little use of the property and in December 1546 handed it over to the City of London to be used for relief of the poor. Having acquired Greyfriars, however, the City appears to have lost interest in its further development, perhaps lacking the necessary funds.

Four years later, after hearing an impassioned sermon by the Bishop of London, Nicholas Ridley, about the plight of London’s poor, the young Edward VI confirmed his father’s gift and, more importantly, provided the institution with an endowment of £600 a year. He commissioned the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Richard Dodd, to take the matter forward and a committee was formed to oversee the project and raise further funds. By November 1552, the buildings had been refurbished and 340 poor, fatherless children were admitted into what then became known as Christ’s Hospital. The term ‘hospital’ at that time signified a place of refuge rather than a medical facility.

The uniform that came to be adopted for the inmates of the Hospital comprised a black cap, a long blue gown with a red belt, and yellow stockings. The colours were chosen for very practical reasons: blue was the colour obtained from a cheap dye and worn by servants and apprentices, while yellow was believed to discourage lice.1 The institution soon gained the alternative name of the Blue Coat School, and its outfit was subsequently copied by other institutions that modelled themselves on Christ’s, such as Queen Elizabeth’s Hospital in Bristol (founded 1586), the Blue Coat School in Canterbury (1574), Lincoln Christ’s Hospital School (1614), the Blue School in Wells (1641), the Reading Blue Coat School (1646) and Chetham’s Hospital in Manchester (1652).

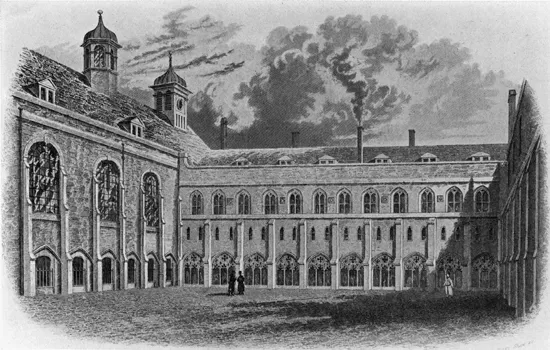

Part of Christ’s Hospital in about 1700. After being severely damaged in the Great Fire of London, its rebuilding was completed in 1705 from designs by Sir Christopher Wren, a governor of the Hospital.

By the eighteenth century, the original London establishment was no longer housing the poorest children, but was boarding and educating ‘the orphans of the lower clergy, officers and indigent gentlemen as could secure nomination by a member of the governing body.’2 In 1902, the school moved to new premises near Horsham, Sussex, where it continues to the present day.

Bridewell

Bishop Ridley also persuaded Edward to give the City another royal property, a little-used former residence of Henry VIII on the banks of the River Fleet, known as Bridewell Palace. Bridewell took on a new lease of life at the end of 1556, with a role somewhere between that of a prison, a workhouse and a reformatory. Its inmates were primarily adults – vagrants, idlers and prostitutes – who, for a period ranging from a few weeks to several years, could be placed under its regime of daily labour and strict discipline. Bridewell’s intake also included the young, however. The orphaned sons of City freemen were received there, parish officials sent destitute children, and the establishment’s own beadles directed others from the streets to its doors.3 As well as receiving a basic education, many of these children became apprentices in one of the numerous trades for which training was provided at the institution, including pin-making, silk and ribbon weaving, hemp dressing, glove-making and carpentry. In 1631, there were sixteen craftsmen teaching their trades to 106 apprentices.4 A number of other towns such as Oxford, Salisbury, Gloucester and Ipswich also set up institutions modelled on Bridewell.

London Corporation of the Poor

In around 1650, almost a century after Bridewell opened its doors, London’s first workhouses proper were set up by the city’s Corporation of the Poor, which was given two confiscated royal properties – Heydon House in the Minories, and the Wardrobe building in Vintry. The Corporation’s provision for the children in its care included the teaching of singing. A verse of one of the children’s songs paints a very rosy picture of their treatment:

In filthy rags we clothed were

In good warm Raiment now appear

From Dunghill to King’s Palace transferred,

Where Education, wholesome Food,

Meat, drink and Lodging, all that’s good

For Soul and Body, are so well prepared.5

In good warm Raiment now appear

From Dunghill to King’s Palace transferred,

Where Education, wholesome Food,

Meat, drink and Lodging, all that’s good

For Soul and Body, are so well prepared.5

Following the Restoration in 1660, when Charles II reclaimed his estates, the Corporation ceased its activities. It was revived in 1698, however, and established a new workhouse on Bishopsgate Street where all the City’s ‘poor children, beggars, vagrants, and other idle and disorderly persons’ were to be accommodated and employed. The ‘poor children’ included those whose family or friends could not support themselves, the children of soldiers and sailors who had died or become incapacitated in the service of the Crown, and petty criminals who might otherwise have ended up facing the gallows. The children, up to 400 in number, were taught to read and write and to cast accounts. They were also employed in tasks such as spinning wool and flax, winding silk, sewing, knitting, and making their own clothes or shoes. Their uniform, made of russet cloth, had a badge on its breast representing a poor boy and a sheep and the motto ‘God’s Providence is our Inheritance’.6

The Bishopsgate workhouse was a substantial edifice, some 400 feet long, and divided into two sections, the Steward’s side, where the children were accommodated, and the Keeper’s side, where the ‘idle and disorderly’ adults were confined. The cost of maintaining the children was mostly covered by payments from their home parish, with funds for the running of the establishment also coming from money raised by the Corporation, from private charities, and from income produced by the children’s own labour.

Charity Schools

Following the example set by Christ’s Hospital, a modest number of other Blue Coat institutions gradually appeared. In the early 1700s, however, a major expansion began to take place in the provision of schools for poor or orphan children, mostly funded by public subscription or private benefaction.

The growth of the charity school movement owed much to its promotion by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), founded in 1698 to ‘spread practical Christianity among the godless poor’.7 The provision of a Christian-based education for the poorest children was seen as a useful way to assist in this endeavour. The Society offered encouragement and advice for those wishing to set up schools, providing sample rules for their operation, and acting as a central co-ordinating body. The curriculum taught in the schools typically comprised reading and writing, plus casting accounts for the boys and sewing for the girls. It also aimed to remind the children of their lowly position in life and the duty and respect that they owed to their betters.

Supporting charity schools became a fashionable activity for the well-to-do and a large number were eventually opened, some notable examples being the Greenwich Blue Coat Girls’ School (1700), the Nottingham Blue Coat School (1706), and the Liverpool Blue Coat School (1708). Others were founded in towns and villages all across the country; in 1792 it was reckoned that a total of 1,631 charity schools had been established since the Reformation.8

Although the majority of charity schools were day schools, some were residential, effectively operating as children’s homes. Typical of these were York’s two subscription charity Schools – the Blue Coat School for boys and Grey Coat School for girls – both founded by York Corporation in 1705 in association with the SPCK. The schools catered for orphans or children from poor, large families, and provided accommodation for forty boys and twenty girls between the ages of 7 and 12. They were taught reading, writing, basic arithmetic and were instructed in the catechism. The boys became apprenticed to tradesmen in the city, while the girls were prepared for domestic service.9 Conditions in the schools sometimes left much to be desired. In 1795, it was reported that the girls at the York Grey Coat School were consistently underfed and ill-treated, their appearance sickly and dejected, and their ignorance extreme. At the same date, children at the London Grey Coat Hospital were said to be utterly wretched from constant flogging and semi-starvation.10

The Foundling Hospital

A significant development in children’s residential care came in 1739 when Captain Thomas Coram founded a new institution for the ‘education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children’. The Foundling Hospital, England’s first charity devoted exclusively to children, opened its doors on 25 March 1741 in temporary premises in Hatton Garden.

Infants up to the age of two months could be deposited at the Hospital, with no information needing to be given about the mother’s identity. Those handing over a baby were asked to leave a ‘mark or token’, such as a ribbon or scrap of material, by which they could identify the child at a future date if required. Infants accepted into the Hospital were baptized and named, then placed with a wet nurse in the country until the age of three. After returning to the Hospital, they were taught to read and ‘brought up to labour to fit their age and sex’.11 At the age of 14, boys were apprenticed into a trade or went to sea. At 16, the girls were placed in domestic service, with some entering into employment at the Hospital.

In September 1742, the foundation stone was laid for the Hospital’s new premises in Bloomsbury Fields to the west of Gray’s Inn Lane. The 56-acre, green-field site, part of the Earl of Salisbury’s estate, cost £6,500, the Earl giving the Hospital a £500 discount on the land’s market value. The new building was intended to accommodate up to 400 children.

Demand for places at the Hospital rapidly exceeded the number available. In October 1742, following unruly scenes when the doors had been opened to admit a new batch of applicants, a system of balloting was introduced using a bag of red, white and black balls. If a mother drew a white ball, her child would be admitted if healthy; a red ball placed them on a waiting list, and black ball meant outright rejection.

The Foundling Hospital became the capital’s most popular charity and was supported by the greatest artists of the time such as Reynolds and Gainsborough who donated paintings. One of its most notable patrons was William Hogarth, himself a foundling, who had no children of his own. He designed the charity’s coat of arms and uniforms for the Hospital’s inmates. He was also appointed as an ‘Inspector for Wet Nurses’, and he and his wife Jane fostered a number of foundling children. Another supporter was the composer George Frideric Handel, who gave benefit performances of his work in the Hospital chapel and also provided it with an organ. The music in the chapel on Sundays became a special attraction and the choir, composed of the children themselves, was assisted at various times by many of the most distinguished singers of the day. After morning service on Sundays, visitors were able to observe the children at dinner.

In 1756, as a condition for receiving a substantial parliamentary grant, the Hospital was required to adopt an open-ended admissions policy, taking any child presented who was under the age of two months (later increased to twelve months). A basket was then placed on the Hospital’s gate where a child could be left and a bell rung to announce its presence to the staff. Perhaps, not surprisingly, the Hospital was inundated with infants from far and wide, many being offloaded from parish workhouses. A trade soon grew up among vagrants who offered, for a fee, to convey an infant to the Hospital. Many such children did not survive their journey or died soon after arrival. Others were just dumped by their courier, who in some cases even removed and sold the child’s clothing. The overall mortality rate in this trade was reckoned to be in the order of 70 per cent.12

Children at play in front of London’s Foundling Hospital in about 1900. Boys and girls had their own separate areas.

The era of indiscriminate admission ended in 1760 when it was calculated that the cost of the exercise had now risen to around £500,000. Parliamentary support for the scheme was withdrawn and the Hospital was forced to rely on its own funds, charitable support, and payments by parishes for the maintenance of children that they placed. From 1756 to 1801, a procedure also operated where a child could be accepted on payment of £100.

Early London Orphanages

From the second half of the eighteenth century, a growing number of other homes or ‘asylums’ for orphan children were founded in and around London. These included the Orphan Working School, Hampstead (1758), the Female Orphan Asylum, Lambeth (1758), the St Pancras Female Orphanage (1776), the Home for Female Orphans, St John’s Wood (1786) and the London Orphan Asylum, Clapton (1813).

The St Anne’s Society (later known as the Royal Asylum of St Anne’s Society) might also be included in this group. The Society was founded in 1702 by Thomas Bray, Robert Nelson, and other gentlemen in the parish of St Anne and St Agnes, Aldersgate. The Society’s initial object was to clothe and educate twelve sons, orphaned or otherwise, of parents who had been reduced to a necessitous condition. It was only in the 1790s that the Society began to provide residential accommodation on a modest scale, moving in 1829 to large, purpose-built premises in Streatham Hill in South London.

Rather more typical of these early institutions was the Female Orphan Asylum in Lambeth. Its founding, in 175...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Early Children’s Homes

- 2. Reformatories, Ragged and Industrial Schools

- 3. Approved Schools

- 4. Training Ships

- 5. The Shaftesbury Homes and ‘Arethusa’

- 6. Müller’s Orphan Houses

- 7. Barnardo’s Homes

- 8. The National Children’s Home

- 9. The Waifs and Strays Society

- 10. Occupational Homes

- 11. Other Voluntary Homes

- 12. Religious Homes

- 13. Children with Disabilities

- 14. Fund Raising

- 15. Poor Law Homes

- 16. Emigration Homes

- 17. Boarding Out/Fostering

- 18. Aftercare and Preventive Work

- 19. Magdalen Homes

- 20. Local Authority Children’s Homes

- 21. Life in Children’s Homes

- 22. Abuse in Children’s Homes

- 23. A Future for Children’s Homes?

- 24. Children’s Home Records

- 25. Useful Resources

- References and Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Children's Homes by Peter Higginbotham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.