- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A historian of the English Civil Wars shares a fascinating study of the seventeenth century New Model Army, examining its formation, tactics, and significance.

The New Model Army was one of the best-known and most effective armies ever raised in England. Oliver Cromwell was both its greatest battlefield commander and the political leader whose position depended on its support. In this meticulously researched and accessible new study, Keith Roberts describes how Cromwell's army was recruited, inspired, organized, trained, and equipped. He also sets its strategic and tactical operation in the context of the theory and practice of warfare in seventeenth-century Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cromwell's War Machine by Keith Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Background to Civil War, 1637-1642

Introduction

Charles I succeeded to the thrones of England (England and Wales), Scotland and Ireland in 1625. These were three separate kingdoms, not a unified state, and he ruled through different political structures in each kingdom. There were underlying political problems in all three but this was by no means unusual for the time, and other European states faced similar problems during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In Europe this was a period of international and religious war, as well as internal unrest. Although there was no single cause for this general instability, there were three common themes which affected European states.

Firstly, religious disputes between Protestant and Catholic had become increasingly interlinked with local provincial rebellion and international warfare in the Low Countries, France and the various states of the German Empire. The same pressures could be seen in Charles’s three kingdoms where religious divisions between Protestant and Catholic were one of the key factors which determined allegiance to one side or the other. Religion was not an absolute factor and alliances were formed between factions in civil war, or between states in international war, which were based on expediency or realpolitik rather than religion. However, once invoked, religious differences could escalate beyond any political control causing any dispute to become polarized, and its adherents to become ever more bitterly and brutally opposed to one another.

Secondly, there was a desire by central governments throughout Europe to rationalize their administration over the various components – kingdoms, provinces, duchies, free cities – over which they ruled. For a centralizing government, local custom and historic forms of local government were seen, then as now, as an inconvenience. But this perspective was not shared by the people whose lives were affected, and most felt allegiance to their locality, their nationality or their religion rather than some distant central government. For the Spanish Empire, whose administration was centred on the kingdom of Castile, this can be seen in several provincial rebellions – the Dutch Revolt in the Low Countries (1567-1648) and, closer to home, uprisings in Aragon in 1591 and Catalonia and Portugal in 1640. The rebellions in Catalonia and Portugal were not connected directly, but the Catalan rebellion certainly demonstrated to the Portuguese that military opposition to the Castilian government was possible. In the event the Catalan rebellion was unsuccessful but Portugal recovered its independence.

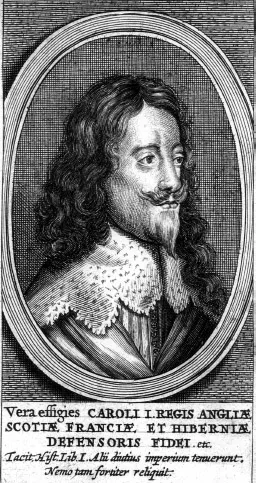

Charles I (1600-1649). King of England, Scotland and Ireland. By the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Scotland had already rebelled successfully and there was an uprising in Ireland.

Thirdly, this period saw rapid inflation, with the actual value of traditional sources of revenue declining while the expenses of government and the display of royal power were increasing. Above all the costs of waging war, or simply stockpiling the military equipment necessary to prepare for it, were escalating as modern war required ever larger numbers of soldiers. The cost of war was the key element as governments could usually manage the day-to-day costs of administration, and while low-level increases in taxation, as with the imposition of ‘ship money’ in England, caused some unrest, this proved to be manageable. But warfare had a huge and, above all, an immediate cost and this was often the catalyst which brought festering discontent to a head. No one likes to pay taxes.

The same three themes can be seen in England, Scotland and Ireland. In England, there was rising discontent during Charles I’s reign over the unpleasant personal experience, as well as the cost, of billeting unpaid soldiers together with the imposition of forced loans to pay for a series of expensive military failures. The English were generally in sympathy with wars against the Spanish and intervention in France in support of French Protestants; it was the failure of these campaigns which made their cost and the government which mismanaged them so unpopular. Charles’s decision to follow a series of shortlived parliaments with a period of personal rule between 1629 and 1640 did little to restore confidence in his government. Nor did his marriage to a Catholic French princess, Henrietta Maria, do much in terms of endearing him to an English popular opinion which had distrusted Catholics since the failed invasion attempt of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and the ‘Gunpowder Plot’ to blow up King and Parliament in 1605. The reforms of Archbishop William Laud, which many English Puritans saw as becoming far too close to Catholic practice, also made the government unpopular during the 1630s. However, although these factors made Charles unpopular and created an underlying sense that the country was not being ruled in the best interests of its people, there was no easy channel through which opposition could be directed and co-ordinated. Although his policies gave rise to discontent, in the absence of regular parliaments there was no effective national opposition to his rule.

The First Bishops’ War (1639)

The catalyst which created conditions whereby unrest could be turned into outright rebellion came in Scotland rather than England. In 1637 Charles I and his adviser Archbishop William Laud sought to impose a new version of the English prayer book on the Protestant Presbyterian church. Political dissatisfaction and violent popular unrest combined to break royal power in Scotland, and opposition was formalized by the drawing up of a National Covenant binding its signatories to support one another and their Presbyterian faith. The Scottish opposition probably expected this stance to form the basis of negotiation, but instead Charles I sought a solution to his Scottish problem by military means, using troops from his other two kingdoms, England and Ireland. In doing so he began the first of the wars which ultimately involved all three of his kingdoms. This was known as the First Bishops’ War as it was seen as an attempt to impose bishops on the Scottish Presbyterian system.

England was the most powerful of the three kingdoms in terms of its potential to provide greater numbers of men, money and military supplies than the other two. The main problems facing Charles I were that he lacked experienced soldiers to form the core of a newly raised army, as well as the money to pay for them and their supplies, and that the war itself was not popular with his English subjects. In the absence of a standing army, King Charles sought to form an army by enforcing the feudal obligations of his nobility and gentry to provide cavalry, by calling out contingents of the Trained Bands (Militia) and by levying conscripts to provide his infantry. In theory the Trained Band soldiers would provide a nucleus of infantry drilled to handle their weapons and deploy in the tactical formations of the day. But in practice many Trained Band soldiers made use of the clause in the King’s orders which allowed them to supply substitutes to go in their place. The general atmosphere of despondency in the English camp after this was expressed by Edmund Verney when he wrote:

our army is very weake, and our supplyes comes slowly to uss, neyther are thos men we have well orderd. The small pox is much in our army; there is a hundred sick of it in one regiment. If the Scotts petition as they ought to doe, I believe they will easily bee heard, but I doubt the roagse [rogues] will be insolent, and knowing our weakness will demand more then in reason or honner the king can graunt, and then wee shall have a filthy business of it. The poorest scabb in Scotland will tell us to our faces that t[w]o parts of Ingland are on theyr sides, and trewly they behave themselves as if all Ingland were soe.1

The Scottish army was probably weaker than Edmund Verney and other Englishmen thought, and in these circumstances both sides were willing to agree a truce termed the ‘Pacification of Berwick’.

The Second Bishops’ War (1640)

The treaty signed at Berwick provided a breathing space rather than a solution for either side, and King Charles lost little time in preparing a new army for another campaign the following year, the Second Bishops’ War. This time he sought to raise funds and national support for his war by summoning Parliament, his first for eleven years. However, the hopes of the King’s advisers that Parliament would be compliant were unfounded, as it set out a long list of grievances for redress before it would vote funds for the King. In response Charles dismissed the Parliament, which became known as the Short Parliament as it had only sat between 13 April and 5 May 1640.

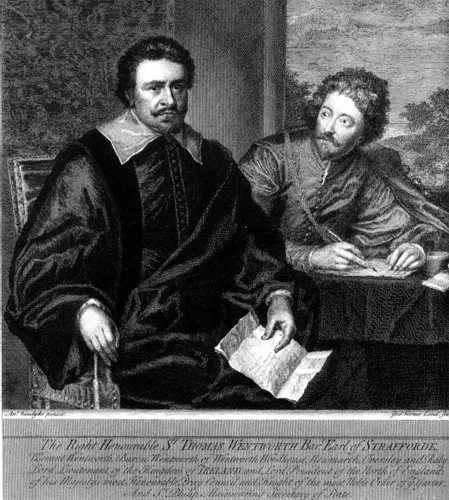

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford (1593-1641). A powerful and ruthless administrator, he was lieutenant governor, then governor, of Ireland. Commander of the English army during the Second Bishops’ War. Impeached for the careless comment that the army raised in Ireland could be used in England, and executed.

English strategy for 1640 envisaged a three-pronged attack on Scotland with a main army on the border, an amphibious landing on the east coast of Scotland and an attack from Ireland using newly levied Catholic Irish troops. Before either of the flanking movements could be made the Scots took the initiative on 20 August and crossed the border into England. This time the Scots sought a decisive action to win their war at a stroke. On 28 August they attacked and overwhelmed an English detachment at the battle of Newburn, and the demoralized English army retreated south, abandoning the city of Newcastle to the Scots. With his army disintegrating and the Scots occupying the north of England, King Charles had no option but to come to an agreement with the Scots, the Treaty of Ripon, for an immediate cessation of hostilities, with further negotiations to be held in London. As a further humiliation the English had to pay the costs of the Scottish army in England at the rate of £850 a day. Charles had now lost control of Scotland and was obliged to summon a new parliament in England to obtain the money that the Scots demanded.

Disarming Catholics. Suspicion of the King’s intentions during 1641 led to heightened concerns over the reliability of English Catholics. An ‘Order was made by both Houses for disarming all the Papists in England’.

The Irish Revolt

The implications of the successful rebellion in Scotland were not lost on the Catholic Irish. Already under pressure from the plantation of English and Scottish Protestant settlers in the north and concerned over the possible enforcement of restrictions on the practice of their faith, Catholics in Ireland were experiencing widespread unrest. England appeared weak and divided politically, and the English garrison in Ireland was small and scattered. There were just thirty-nine companies of infantry and fourteen troops of horse in the garrison,2 a total of around 2,300 infantry and 1,000 cavalry.

This force was outnumbered by a stronger body of Catholic soldiers in Ireland. One of Charles I’s more disastrous decisions during the Bishops’ Wars had been the acceptance of a suggestion by the Earl of Strafford to raise an army of 8,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry from amongst the Catholic Irish for service against the Scots. While there was some logic in using Catholic soldiers against Scottish Presbyterians, these regiments represented a serious danger to the English government in Ireland. When the Scots’ success at the battle of Newburn brought King Charles’s campaign to an abrupt end, the soldiers refused to disband without settlement of their arrears of pay. This army now represented an obvious problem, as the Venetian ambassador to London reported:

the 10,000 [sic] foot and 1,000 horse, assembled these last months by His Majesty’s order to be sent to Scotland, now refuse to disband, after the need for them has passed, as they wish first to hear what satisfaction their delegates will bring back from the King. So it is to be feared that if they do not promptly grant some satisfaction to that people, a fresh fire will break out in Ireland also, no less difficult to quench than the others (i.e. in Scotland).3

The King’s reasons for retaining this army in being, apart from the genuine difficulty of finding the £10,000 necessary to pay its arrears, remain unclear. It represented a clear threat to the security of English rule in Ireland as it outnumbered the small and scattered English garrison. Perhaps more importantly from Charles I’s perspective at that point, the Catholic Irish army could be used as part of the bargaining in negotiations with the Scots – who remained concerned that it might still be used against them for a landing in western Scotland – and, possibly, with the English Parliament. There were also ongoing negotiations with Spanish representatives willing to pay generously to have the whole Catholic Irish army shipped overseas for service with the Spanish army. Whatever the reason for the delay, few soldiers had been shipped to Spain by the time the Irish rebellion broke out, and the addition of thousands of trained men represented a real advantage to the newly raised rebel armies.

The Irish rebellion began on the night of 22/23 October 1641. An attempt to take control of Dublin, the seat of English government and the location of the main arsenal in Ireland, failed. But elsewhere the rebellion took hold across Ireland with the Catholic Irish driving out or massacring English and Scottish Protestant settlers. The numbers killed were exaggerated, and the numbers grew in the telling, but the underlying reality was the murder of settlers and their families. This bloody beginning set a pattern of atrocity and reprisal which then continued throughout the campaigns in Ireland. Without siege artillery the new Irish armies could not break into Dublin and other fortified strong points, and the English and Scottish settlers looked to their home countries for support.

As Parliament and King were unable to agree over the appointment of the officers who would command an English army for service in Ireland, a compromise solution was agreed whereby a Scottish army would be sent, paid for by England. The Scots were willing to do this partly because Protestant Scottish settlers were being killed or driven from their settlements in Ulster, but also because English strategy during the Bishops’ Wars had shown that Scotland was vulnerable to attack from northern Ireland. Geographically, there was only a short sea crossing between the coast of the Irish province of Ulster and the western lowlands of Scotland or the highlands.

The threat to the Scottish lowlands was invasion by regular soldiers, but the threat to the highlands was intervention in clan warfare. The dominant clan in the highlands was the Protestant Clan Campbell whose head, Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll, was a leading figure in the Scottish Covenanting government in Edinburgh. The Campbells had successfully crushed their opponents the MacDonalds in the Scottish highlands, but the Irish branch of the clan, led by the Earl of Antrim, was a strong presence in Ulster. The Earl of Antrim had made unsuccessful attempts to obtain English support for an invasion of the highlands, essentially an attack on the Campbells, as part of Charles I’s strategy for the Second Bishops’ War. For the Scottish government in Edinburgh the presence of a Scottish army in Ulster would reduce the risk of invasion from Ireland, and for the Earl of Argyll and the Campbells it offered an opportunity to crush clan enemies. This was also a chance to use circumstance to keep a substantial Scottish army under arms, paid for by England, which could easily be withdrawn by sea back to Scotland. The impact of the Scottish army in Ireland was restricted by the strategic aims of the Scottish government and, while it was useful in securing Ulster – the gateway for any invasion of Scotland from Ireland – it proved unwilling to march far outside it.

The Civil War in England, 1642-1644

The Civil War Begins: 1642

The Civil War Begins: 1642

There is no single or simple reason why opposition to the King and his ministers moved from protest to armed revolt in 1642. Generations of historians have debated this, often interpreting political events from the perspective of the politics of their own ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658)

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Background to Civil War, 1637-1642

- Chapter 2 The European Background: War, Politics and the Military Revolution

- Chapter 3 Recruitment, Uniform, Arms and Equipment

- Chapter 4 Training Methods and Training Manuals

- Chapter 5 Pay, Rations and Free Quarter

- Chapter 6 Regiments, Roles and Responsibilities

- Chapter 7 Strategy, Tactics and Siege Warfare

- Chapter 8 Professionalism: Honour, Self-Respect and Symbolism

- Chapter 9 Military Life in Camp and Garrison

- Chapter 10 From Victory to Mutiny

- Chapter 11 Mutiny

- Chapter 12 The Campaigns of the New Model Army, 1648-1653

- Chapter 13 The Rise and Fall of a New World Power

- Notes

- Index