- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

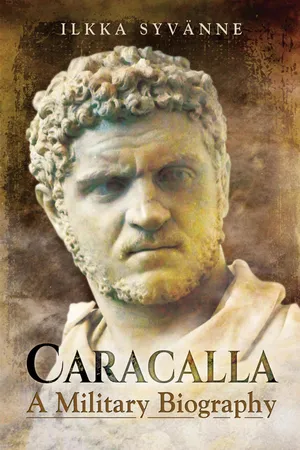

This biography of the Roman Emperor Caracalla challenges his tyrannical reputation with a revealing narrative of his social reforms and military campaigns.

Caracalla has one of the worst reputations of any Roman Emperor. Many ancient historians were very hostile, and the 18th century English historian Edward Gibbon even dubbed him the common enemy of mankind. Yet his reign was considered by at least one Roman author to be the apogee of the Roman Empire. He was guilty of many murders and massacres—including that of his own brother, ex-wife and daughter. Yet he instituted the Antonine Constitution, granting citizenship to all free men in the Empire. He was also popular with the army, improving their pay and cultivating the image of sharing their hardships.Historian Ilkka Syvanne explains how the biased ancient sources in combination with the stern looking statues of the emperor have created a distorted image of the man. He then reconstructs a chronology of Caracalla's reign, focusing on his military campaigns and reforms, to offer a balanced view of his legacy. Caracalla offers the first complete overview of the policies, events and conflicts he oversaw and explains how and why these contributed to the military crisis of the third century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Caracalla by Ilkka Syvänne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías militares. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Background

1.1. Roman Society

Roman society was a class-based society that consisted of judicial and social hierarchies. The judicial hierarchy divided the populace into freemen and slaves. The freemen in their turn consisted of freeborn men and freedmen, with the former consisting of Roman citizens and tribesmen with varying rights. Slaves could become freedmen when they either managed to buy their freedom or their master granted them freedom. The freedmen had no political rights, but their children were freeborn men with full rights. In addition to this, there existed a third class of freeborn: the provincials, who did not have Roman citizenship. Their legal position varied greatly according to the treaties their nations or cities had made with Rome and according to the legal systems they had in place in their own territories.

The official social categories consisted of the senatorial order, the equestrian order and the plebs. The senatorial order was hereditary but could receive new blood when the emperor so desired. Its members consisted of Roman citizens with a minimum property of 1 million sesterces. The most important military and civilian offices of the empire were the privilege of the senatorial class. One of the ways in which the emperors rewarded their supporters was to nominate them as senators. As a result of this, most of the senators consisted of provincials by the beginning of the third century AD. Since it was dangerous for emperors to allow the wealthy senators to be anywhere near the legions, senators had an obligation to reside at Rome and to invest one third of their property in Italy. Senators were allowed to travel away from Italy only with the approval of the emperor. Senators wore toga laticlavius (broad-stripe) as a sign of their social standing. They were liable to pay only donatives (paid every five years, or when the army campaigned, or to celebrate some important occasion) and very small inheritance taxes. This meant that the wealthiest citizens, who owned most of the property, contributed only a very small proportion of the imperial taxes.

The equestrian order was a non-hereditary order, the members of which consisted of Roman citizens with a minimum property of 400,000 sesterces, who had successfully applied to be enrolled into its ranks. The reason for the willingness to be enrolled among the order was that some of the positions in the imperial administration and armed forces were reserved for equestrians. The most successful of the equestrians could hope to be enrolled among the senatorial order. The equestrians consisted of those who had inherited money or who were selfmade men. They wore the toga angusticlavius in public as an indication of their rank. Ever since the first century, the emperors had promoted the relative position of the equestrian order vis-à-vis the senatorial order by increasing its role in the imperial administration and the military. The reason for this was that the emperors considered the members of the heterogeneous equestrian order to be generally more loyal and professional than the senators. The most important demonstration of this was that the emperors had reserved the most important military positions – the two or three praetorian prefects – for the members of the equestrian order. As we shall see, the trust that the emperors placed on the loyalty of the equestrians and praetorian prefects was entirely misplaced.

The vast majority of the free population consisted of the plebs. This order included both rich and poor. The richest members of the plebs (decurions with citizenship) were allowed to wear the toga praetexta to separate them from the middle-class and poor. The rest of the plebs consisted of the rich (businessmen, merchants and bankers etc.), the ‘middle-class’ plebs (artisans, boutique keepers, merchants, bakers, artists, intellectuals/philosophers etc.) and the poor plebs (peasants, carriers, labourers etc.).

The civilian and military officers followed in theory the so-called cursus honorum. This system reserved certain posts for the members of the senatorial order and others for the equestrian order, with the very highest posts the prerogative of the former. However, in practice the emperors often bypassed these requirements and appointed equestrians or even imperial freedmen to the highest offices. Even more importantly, the top military commands of the empire, the posts of the praetorian prefects, were reserved for members of the equestrian order, as noted above. The same was true with the very important post of the prefect of Egypt and with the new prefectures of the three Parthian legions created by Septimius Severus.

In truth, the class structure of society was not as clear as the official divisions would imply. In practice, the emperor and the imperial family formed a separate privileged class above the rest, just as did the members of the former imperial families. The friends of the emperor – who could consist of senators, equestrians, freedmen and even trusted slaves – and the imperial women could also wield unofficial power far in excess of their official standing, thanks to their closeness to the emperor. In addition to this, from about the mid-second century onwards, the old judicial and social standings and divisions started to disappear. The older divisions were superseded partially by a new form of class division which divided the people into honestiores and humiliores. The honestiores consisted of the senators, equestrians, veterans and decuriones. They had legal privileges and exemptions from the harsher punishments to separate them from the humiliores. This is believed to have resulted from decisions undertaken by Hadrian, Antoninus Pius or Marcus Aurelius. At about the same time as the emperors created the honestiores class, they also created honorary ranks with judicial privileges. It is usually assumed that Marcus Aurelius was the first emperor to do so, but it is possible that this decision was already made under Hadrian. The praetorian prefects obtained the rank of viri eminentissimi, the senators the rank of clarissimus and the officials of the court the rank of perfectissimi. The aim of this policy was clearly to reward those members of society who contributed most to the state in the form of taxes and/or administrative and military duties. The goal was to secure their loyalty to the emperor. This was very important in light of the fact that an emperor’s position depended on his ability to retain the loyalty of his military officers and administrators, and his ability to collect taxes through the civilian decurions. The latter position was becoming less and less desirable in the eyes of the rich city dwellers because the members of the city councils were required to pay any tax arrears.

Agriculture formed the basis of the Roman economy, but in contrast to most of its neighbours the empire also had very significant artisan and merchant classes. This meant that most of the tax income was collected from the peasants through the city councils for use by the imperial administration. It was thanks to this that the Romans were always eager to settle foreign tribes within their borders to till the land and provide soldiers. The emperors could not rely solely on the taxes obtained from the peasants, because it varied from one year to another depending on the size of the crops. It was due to this that the emperors tapped other sources of income. These consisted of the produce of the imperial estates and mines, donatives, extraordinary taxes levied when needed, confiscation of the property of the rich with various excuses like faked charges, conscription of soldiers (or its threat to produce money) and tolls and customs (collected from internal and external trade). The customs collected from long-distance trade with Arabia, Africa, India and China formed one of the most important sources of revenue for the emperor. It should not be forgotten that the emperors needed money for the upkeep of the imperial machinery and armed forces, the latter of which consumed most of the revenue. If everything else had failed, emperors even resorted to the selling of imperial property or on loans or forced loans from the wealthy senators, equestrians and bankers.

1.2. Governing the Empire

The Emperor

The Roman Empire was officially a republic in which the emperor, the princeps (the first among equals/first citizen), possessed executive (proconsul) and legislative powers (people’s tribune). He also acted as commander-in-chief of the armed forces (proconsul and imperator) and was the high priest of the empire (pontifex maximus). In addition to this, the emperor possessed informal power over the senators and people, which was publicly recognized under the name auctoritas (influence) and with the official surname Augustus. On his death, the emperor would also become a god. In practice, the emperor therefore possessed the executive, legislative and judiciary powers, and controlled Rome’s foreign policy and military forces, appointed all civil and military functionaries, proposed and legislated imperial legislation and acted as the Supreme Court. However, in truth, the emperor’s powers rested solely on his control of the military machinery. The soldiers had already learnt in the first century AD that they could nominate their own commanders as emperors. The latest example of this was obviously the rise of Septimius Severus.

There were several inherent weaknesses in this system, but the most important were: 1) the principate did not establish an orderly system of succession; and 2) the emperors could not place any gifted commander in charge of large military forces without the risk of being overthrown by this general. It should still be stressed that even if the emperor’s right to rule rested solely on his control of the military forces, as was so well understood by Septimius Severus and Caracalla, it was still necessary for the emperor to court the important members of the senatorial and equestrian classes because their members still formed the moneyed elite of the society, members of which filled up almost al...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Plates

- List of Maps

- Introduction

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Background

- Chapter 2 Youth and Education

- Chapter 3 The Military Education: the Campaigns of 207–211

- Chapter 4 The Joint Rule: Antoninus (211–217) and his Hapless Brother Geta (211–212)

- Chapter 5 Antoninus Caracalla Takes Power

- Chapter 6 German Campaign 212–213: Antoninus Imperator, Germanicus Maximus, Pacator Orbis, Magnus

- Chapter 7 Caracalla’s Anabasis Phase 1: Caracalla the Geticus and the Preparations in 214

- Chapter 8 Caracalla’s Anabasis Phase 2: Caracalla Arrives in Asia to make Further Preparations

- Chapter 9 Caracalla’s Anabasis Phase 3: Campaigns in Armenia and Alexandria, 215

- Chapter 10 Caracalla’s Anabasis Phase 4: Campaign Against Artabanus in 216

- Chapter 11 Caracalla’s Anabasis Phase 5: Army at Winter Quarters and the Death of Caracalla, 216–217

- Chapter 12 The Apogee of Rome: The Reign of Caracalla Magnus, ‘The Ausonian Beast’ (211–217)

- Chapter 13 An Epilogue: The Reign of Macrinus the Effeminate, 217–218

- Appendix I: The Family of Caracalla

- Appendix II: Julius Africanus and Severan Military Science

- Appendix III: The Georgian Chronicles and Caracalla’s Campaign in Armenia

- Select Bibliography

- Plate section