eBook - ePub

Arctic Snow to Dust of Normandy

The Extraordinary Wartime Exploits of a Naval Special Agent

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Arctic Snow to Dust of Normandy

The Extraordinary Wartime Exploits of a Naval Special Agent

About this book

A memoir from the real-life James Bond, who "could ski backward, navigate a midget submarine and undertake the riskiest parachute jumps" (

Wired).

In 1939, as a young man, Patrick Dalzel-Job sailed a small brigantine along the Arctic coast of Norway to the Russian border. His crew consisted of an aged mother and a blue-eyed Norwegian schoolgirl. In the following four-and-a-half years of war, Patrick had many adventures which he recounts in this charming book. His local knowledge and language skills made him invaluable in 1940 and he moved more than 10,000 soldiers of the ill-fated Allied North West Expeditionary Force without loss. Then, acting against specific orders, he used his boats to evacuate all the women, children and elderly from Narvik just before it was destroyed by German bombers. He only escaped a court-martial when the King of Norway sent personal thanks to the British Admiralty and presented Patrick with the Knight's Cross of St Olav.

His later escapades included spells spying on enemy shipping under conditions of great hardship and danger. In 1944/45 he commanded a team of Ian Fleming's "30 AU" working far in advance of the Allied advance in France and Germany. There is strong anecdotal evidence that Fleming based his James Bond character on Patrick. As if this were not enough, Patrick defied authority to return to Norway in June 1945 and seek out the blue-eyed schoolgirl he had had to leave behind. After much difficulty he found her, now a beautiful young woman, and three weeks later married her. They lived together in Scotland until her death.

In 1939, as a young man, Patrick Dalzel-Job sailed a small brigantine along the Arctic coast of Norway to the Russian border. His crew consisted of an aged mother and a blue-eyed Norwegian schoolgirl. In the following four-and-a-half years of war, Patrick had many adventures which he recounts in this charming book. His local knowledge and language skills made him invaluable in 1940 and he moved more than 10,000 soldiers of the ill-fated Allied North West Expeditionary Force without loss. Then, acting against specific orders, he used his boats to evacuate all the women, children and elderly from Narvik just before it was destroyed by German bombers. He only escaped a court-martial when the King of Norway sent personal thanks to the British Admiralty and presented Patrick with the Knight's Cross of St Olav.

His later escapades included spells spying on enemy shipping under conditions of great hardship and danger. In 1944/45 he commanded a team of Ian Fleming's "30 AU" working far in advance of the Allied advance in France and Germany. There is strong anecdotal evidence that Fleming based his James Bond character on Patrick. As if this were not enough, Patrick defied authority to return to Norway in June 1945 and seek out the blue-eyed schoolgirl he had had to leave behind. After much difficulty he found her, now a beautiful young woman, and three weeks later married her. They lived together in Scotland until her death.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arctic Snow to Dust of Normandy by Patrick Dalzel-Job in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781783033065Subtopic

Military Biographies1

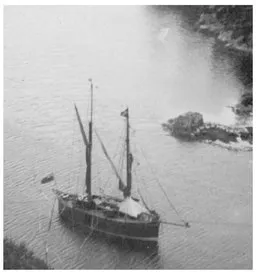

North-Eastwards to Norway

Norway was calling me. By 1937 I thought I knew enough to cross the North Sea and in July of that year Mary Fortune sailed from Fraserburgh in North-East Scotland. All through the first day we passed score upon score of fishing craft, provoking a lively interest. Later, we sailed across an empty sea, bounded by a hazy blue horizon. The schooner carried jib, fore-staysail, fore-topsail, main-staysail, mainsail and main-topsail, but she made slow speed until dusk, when the wind freshened from a greying southern sky. By nightfall we were carrying nothing but the jib and square fore-course, reaching fast with a rising sea. I lashed the tiller and dozed beside it as we rushed onwards into the night.

About midnight, a crash of heavy spray aroused me. We were scudding now, with the fore-course straining to leeward and with breaking seas glowing alternately green and red in the navigation lamp-lights. A more experienced seaman might have carried on, but I thought it better to be on the safe side, so I hove to under main-staysail and slept very peacefully until daylight.

The gale – for so it was at times – soon blew itself out and left a windless calm, with a very big swell. Reluctantly, I started the engine, which was that old friend of Scottish fishermen, a thirteen horse power Kelvin ‘poppet’, and we chugged slowly and uncomfortably towards Norway all that day, entering fog at nightfall. At dawn, the weather cleared suddenly and the wind came fresh and cold from right ahead, veering southerly and increasing to gale force by 10.00. I hove to again under main-staysail. The horizon was clear, and I went below at about noon, to get a bowl of hot soup from my mother in the dry, warm cabin.

Mary Fortune on Loch Fyne, sailing for Norway, June 1937.

While I was below there was a great crash and two seas, one after the other, struck the fore part of the schooner on the starboard side. A few drops of water found their way through the watertight fore-hitch, and Mary Fortune began to roll to port. When I got back on deck, she was lying nearly on her beam-ends on the lee side of a breaking sea.

I dragged myself forward against the wind, and streamed the sea-anchor – a big and heavy canvas drogue – on thirty fathoms of coir warp. With the double-reefed mainsail sheeted flat aft, instead of the main-staysail, Mary Fortune came head to wind and thus we lay in great comfort all the third day. At times, the top of the mainmast was below a line from breaking crest to breaking crest. In the late afternoon, the wind fell light again, and I set all sail. I tried also to start the engine, but a bearing had failed owing to a clogged oil-drip, so it seemed that I would have to make port in Norway under sail alone. I have always been glad that this was forced upon me.

We entered fog again, and rolled slowly on our way. Then, for the first time, I heard that noise which was to be so familiar to me later, in peace and war – the ‘tunn-tunn-tunn-tunn’ of a Norwegian fishing boat’s single-cylinder engine. In the fog, we could see nothing.

The wind freshened, and on the morning of the fourth day we saw the sun again. I got several sextant-sights, and found ourselves to be within five miles of my estimated position. Early that evening, we saw a dim shadow on the port bow; it was the island of Utsire, and when I had fixed our position by the lighthouse I was able to alter course for the southern end of Karmøy, which lies some way outside Stavanger.

The sun went down in a glorious flow of crimson over the North Sea behind us, and then the Norwegian coast lighthouses came to life. We entered the red sector of Skudenes light, and kept in it, passing close southwards to the islet of Gjeitungen, until that light had changed from occulting, through group occulting, group flashing and again occulting, to red occulting. Now we turned eastwards in the last sector, seeming (in the darkness) to glide silently within only a few feet of numberless rocks and islets.

Vikeholm light came in sight, and changed from red to white on our port quarter. We turned towards it, and beat up tack and tack within the white sector, north-westwards. The land had almost killed the wind; it was a warm, gentle wind, scented with the shore, but it could no longer do us any good, so I dropped anchor at midnight on Norwegian ground, very close to the rocks below Vikeholm light. After this came five hours of pulling and hauling, sometimes towing from the small boat which we had carried on deck, but mostly warping from one or other side of the rock channel.

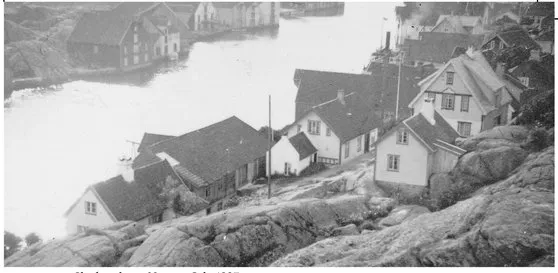

Skudeneshavn, Norway, July 1937.

By two o’clock in the morning, it was already broad daylight, and a rosy-golden dawn lit the painted wooden houses that jostled each other all along the shores of the inlet. The sky above the islands was flecked with clouds, pink in the sunrise, and the silence was complete, so that my voice sounded startlingly loud when I called across the water to Mary Fortune. It was like entering a toy town in a northern fairyland, with a toy lighthouse winking on the island as the only sign that there really were people inside those painted houses.

Slowly, slowly, Mary Fortune made her way up the harbour, her green topsides glistening with dew and her brown sails furled against the masts. The red ensign hung limply from the mainpeak, and the yellow flat requesting pratique flapped lazily from the yard-arm.

We came to a short quay that seemed less like somebody’s front garden than the others. A lifebuoy hung on a shed, and a gravel road led away inland, so I made fast to iron hooks, tidied the decks and rigging for a Sunday in harbour, and went to bed.

About nine o’clock, I awoke to a crescendo babble of voices. Pushing my sleeply head through the cabin-hatch, I discovered the little wharf to be no longer silent and deserted, but packed to overflowing with scores of children – chattering, flaxen-haired children in white shirts and trousers or clean cotton frocks. Behind the children there stood (it seemed to me) the whole population of Skudeneshavn. We had arrived; and already I had lost my heart to Norway, and above all to Norwegian children.

We lingered long in sunny, idle days at Skudeneshavn, with the excellent excuse of awaiting spares for the Kelvin engine. British yachts had not found their way to Norway then, as they have in such numbers since the War; there had never been a British yacht in Skudeneshavn when we were there, and there had been no British visitor of any kind for fourteen years. No wonder we were charmed by the hospitable welcome we received, and by the unaffected friendliness.

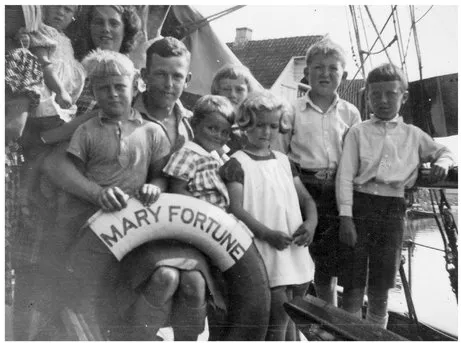

The author, Patrick, with some Norwegian children on Mary Fortune, July 1937.

The readiness of Norwegian people to initiate conversation with a stranger was a great pleasure to me. My unusual upbringing combined with some natural shyness often made new social contacts an ordeal, but Norwegian children (in particular) seemed to like me, and they provided me with many introductions.

Of the adults of any nation it is seldom wise to generalize; but I will be bold enough to say that there are no more charming and delightful children in the world than Norwegian children. Their clean and healthy appearance, frank and friendly ways, and remarkably good manners were a joy to see. Before the War at least – and still now in the better families – little boys were taught to bow to their elders and to strangers, and little girls to curtsy. My wife even curtseyed to me when we first met, but that was a long way from Skudeneshavn.

I told my mother that we would stay a year or two in Norway, and when I had repaired the schooner’s engine we set about exploring the deep fjords between Stavanger and Bergen.

I was intrigued by the very narrow channels and tiny anchorages, of which there were so many; and I soon learned to use Norwegian charts, and to drop an anchor in deep water close inshore, taking a line to an iron ring or post on the rocks. These rings and posts have existed in every anchorage all round the coast of Norway for hundreds of years – the holes for some of them were made a thousand years ago. They are now marked by black and white ‘targets’ painted on the rock face alongside, and this sign means in effect ‘good anchorage here’. The principle is that the anchor will not drag up the steep bottom, while the rope to the shore keeps the ship from blowing off the land. Holes in the rocks, which might have been made for mooring pins of this kind, are said to exist in some places on the north-east coast of North America, and may be evidence that Norsemen sailed that way many years ago from Greenland.

For a schooner worked by one man, weighing anchor in deep water so close to the rocks could be difficult at times, but I had a ‘Heath Robinson’ affair of pulleys and chains which enabled the engine to do the hauling for me, with much clattering, but very effectively. As the years went by, I evolved all kinds of ingenious ways of working and living in my schooner; people who did not like Mary Fortune called it ‘misplaced ingenuity’. What these people did not know was that I could not have afforded the cost of more orthodox gear and methods, even if I had liked them (which, to be honest, I often did not). This was one reason why Mary Fortune carried outdated brigantine rig instead of modern and efficient Bermudan sails, and why her windlass was driven by a rattling endless chain instead of by a hydraulic motor.

The late autumn gales warned us to seek a safe winter berth, while we were still exploring the inner arms of the hundred-mile length of Hardangerfjord, surrounded by steep mountains and the glint of glaciers. I chose the little village – as it was then – of Norheimsund, and we lay there very comfortably until the spring of 1938.

Hardangerfjord, September 1937.

That first winter in Norway began to teach me how to make the little schooner into a snug home, even with snow on deck and ice near by. As time went on, I fitted extra insulation under the deck, four separate layers of glass to the hatches to stop condensation, as well as other refinements, and I improved my battery of ducted oil heaters until we were able to face even an Arctic winter in comfort.

Norheimsund, 1937.

I now had time to turn my thoughts to matters of wider import, and I wondered whether the British Government and War Office had given any consideration to such matters.

After the little I had already seen of Norway’s west coast, I had come to believe that this vast area of fjords, channels, islands and rocks would be a battleground for small, fast boats in time of war. The belief turned into an obsession; I went by passenger ship to England, although it was an expense I could ill afford, I managed to make contact with a department of Admiralty which might be expected to be interested, and I told them what I thought. I said I was likely to be at least two years exploring all of the coast as far as the Arctic Russian boarder, and I offered to make detailed plans of all the places where small craft might hide in time of war. Admiralty was clearly not very interested, but would accept whatever I might send.

I returned to my schooner in Norway. In the event, there was no organization in London for filing the carefully prepared information which I began to send as we sailed northwards. When it was badly needed a few years later, the information could not be found. By that time, topographical detail about all enemy-occupied coasts was becoming a vital necessity for the conduct of the war, and Admiralty was seeking everywhere for anything, even picture postcards, to that end. One wonders how many ships and lives were lost because of pre-war negligence.

In 1939, there was an even more blatant case of Admiralty negligence. A sympathetic Norwegian Ship Master (most of them were sympathetic) turned up in London with an enormous bundle of Norwegian charts, covering the whole coast. He said he no longer needed the charts, and he thought they might be useful to the Royal Navy.

The Norwegian charts of their own coasts are uniquely important to anyone needing to use the inshore channels. The whole length from the Skagerrak to the Arctic is covered by charts on the same large scale, showing every small rock and channel and all the myriad perches and other seamarks. Most important of all, the sectors of all the automatic lights which mark every channel are drawn and are coloured on the charts. This system is extraordinarily effective, the sectors being extremely accurate and often very narrow; the permutations vary between two white sectors, which means safety for big ships, through green for smaller vessels, to two red lights – which mean that you are aground! Even the express costal steamers navigated entirely by light-sectors at night and never took bearings. Without charts showing the sectors in colour, movement at night in those waters was impossible. Admiralty charts were copied from the Norwegian ones, but only a few were on the large scale of the originals. Many of the light sectors were omitted, and none were shown in colour on the British charts.

The Norwegian Ship Master was thanked for this unexpected gift of charts, and went on his way. The naval officer who had received the charts could not think what to do with them, so he shoved the whole lot behind a steel cabinet. It was years later, when the war was nearly over, that the Arctic explorer Augustine Courtauld had a temporary staff job in Admiralty and chanced to move the steel cabinet. Out fell the charts. ...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 - North-Eastwards to Norway

- 2 - The Arctic – Prelude to War

- 3 - Frustration

- 4 - Return to Norway

- 5 - Narvik

- 6 - Operation ‘VP’

- 7 - Midget Submarines

- 8 - Alone on a Norwegian Island

- 9 - Parachuting

- 10 - NID 30 and 30 AU

- 11 - Behind Enemy Lines

- 12 - Onwards into the Reich

- 13 - Heinschenwalde and Bremerhaven

- 14 - Journey’s End

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- MAPS