- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

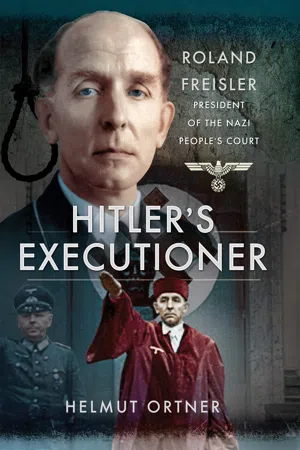

The biography of the infamous judge who oversaw Nazi justice for the Third Reich as president of the "People's Court."

Though little known, the name of the judge Roland Freisler is inextricably linked to the judiciary in Nazi Germany. As well as serving as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice, he was the notorious president of the "People's Court," a man directly responsible for more than 2,200 death sentences; with almost no exceptions, cases in the "People's Court" had predetermined guilty verdicts.

It was Freisler, for example, who tried three activists of the White Rose resistance movement in February 1943. He found them guilty of treason and sentenced the trio to death by beheading; a sentence carried out the same day by guillotine. In August 1944, Freisler played a central role in the show trials that followed the failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler on 20 July that year—a plot known more commonly as Operation Valkyrie. Many of the ringleaders were tried by Freisler in the "People's Court." Nearly all of those found guilty were sentenced to death by hanging, the sentences being carried out within two hours of the verdicts being passed.

Roland Freisler's mastery of legal texts and dramatic courtroom verbal dexterity made him the most feared judge in the Third Reich. In this in-depth examination, Helmut Ortner not only investigates the development and judgments of the Nazi tribunal, but the career of Freisler, a man who was killed in February 1945 during an Allied air raid.

Though little known, the name of the judge Roland Freisler is inextricably linked to the judiciary in Nazi Germany. As well as serving as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice, he was the notorious president of the "People's Court," a man directly responsible for more than 2,200 death sentences; with almost no exceptions, cases in the "People's Court" had predetermined guilty verdicts.

It was Freisler, for example, who tried three activists of the White Rose resistance movement in February 1943. He found them guilty of treason and sentenced the trio to death by beheading; a sentence carried out the same day by guillotine. In August 1944, Freisler played a central role in the show trials that followed the failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler on 20 July that year—a plot known more commonly as Operation Valkyrie. Many of the ringleaders were tried by Freisler in the "People's Court." Nearly all of those found guilty were sentenced to death by hanging, the sentences being carried out within two hours of the verdicts being passed.

Roland Freisler's mastery of legal texts and dramatic courtroom verbal dexterity made him the most feared judge in the Third Reich. In this in-depth examination, Helmut Ortner not only investigates the development and judgments of the Nazi tribunal, but the career of Freisler, a man who was killed in February 1945 during an Allied air raid.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hitler's Executioner by Helmut Ortner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Law Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Ceremony

On the morning of 14 July 1934, a select group of prominent jurists and National Socialist Party members gathered in Berlin at Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 2. There, in the building that had formerly housed the now disbanded Landtag (state parliament) of Prussia, everything had been meticulously prepared for the dramatic first appearance of the newly-formed Volksgerichtshof. At the front of the assembly hall, two huge swastika flags hung from the gallery to the floor. Between them stood a row of Nazi standard-bearers wearing highly-polished boots and forbidding expressions. Ornamental bushes and flower boxes were arranged in front of the speaker’s podium, lending an austere freshness to the scene.

The rows of chairs facing the podium filled the whole chamber. Seated on them were the distinguished guests, wearing suits or uniforms, in the seats of honour Reichsführer-SS (Commander of the SS) Heinrich Himmler and beside him, Minister of Justice Franz Gürtner, who had held office for two years, and Reich Justice Commissioner Hans Frank. The president of the Reichsgericht, the supreme civil and criminal court, Erwin Bumke, and Oberreichsanwalt (senior Reich prosecutor) Karl Werner had arrived from Leipzig, where the court was based. Behind them sat representatives of the SA and SS, the Wehrmacht and judicial administration departments. And finally, in the last two rows, sat the thirty-two judges and associate judges of the new Volksgerichtshof, waiting to take the oath of office in their new place of work.

Originally, the ceremony was to have taken place twelve days earlier, but the Nazi leaders were otherwise engaged at the time. They were busy directing the extrajudicial executions of the ‘conspirators’ of the ‘Röhm Putsch’ (The Night of the Long Knives). Shortly after the Nazis seized power in 1933, the leader of the SA, Ernst Röhm, had already boldly expressed ambitions to take control of inner-political developments in Germany. Röhm supported the idea of a ‘second revolution’ which would have given the army of Brownshirts wide access to government offices, increasing their power and influence. Hitler saw this as a threat to the inner homogeneity of Nazi organizations and called Röhm a ‘rootless revolutionary’. Together with the other leaders of the NSDAP, he decided to liquidate Röhm and his followers. In a cloak-and-dagger operation, Röhm and a series of other high-ranking SA men, including Gregor Strasser, were murdered. Even politicians and military personnel with no direct connection to Röhm fell victim to the rigorous purge that took place between 30 June and 2 July. Without a trial and often without even questioning them, Hitler’s death squads murdered members of the SA and SA sympathizers, including his predecessor as Chancellor, General Kurt von Schleicher, and his wife. This bloodbath, in the course of which Hitler rid himself of former comrades-in-arms who had fallen out of favour, claimed more than 200 lives. And so there had been no time for a grand opening of the Volksgerichtshof. Now, the massacre over, there was time to celebrate.

In his opening speech, before the members of the new Volksgerichtshof were sworn in, Justice Minister Gürtner referred to the events of 30 June. He saw the ‘putsch’ as an illustration of just how critical the danger of ‘violence’ against the Reich was and how necessary it was to have effective legislation in place. Gürtner’s demeanour was theatrical, his words unctuous. And for those in the chamber who may have been so moved that they were unable to follow the justice minister’s words, the speech was printed verbatim in the next day’s edition of the party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter:

In this solemn ceremony to which I have invited you here today, the Volksgerichtshof for the German Reich convenes. Through the confidence placed in you by the Reich Chancellor, you, gentlemen, have been appointed judges at the Volksgerichtshof. As your first act, you will swear a solemn oath to carry out your duties faithfully. Every people, no matter how healthy, every state, no matter how firmly established, must remain in a state of constant vigilance lest it fall victim to an attack such as that of 30 June. Such an attack does not always take the form of imminent violence, which can only be suppressed by means of direct violence. All too often, acts of treason and high treason are preceded by lengthy and widespread preparations which are not always easily recognized and which draw many – both guilty and even completely innocent parties – into their wake.

The sword of the law and the scales of justice will lie in your hands. Together, they symbolize the power of the judge’s office, an office which the German people in particular has always held in deep reverence and on which it has bestowed the independence necessary to follow the conscience.

I know, gentlemen, that you are imbued with the solemn gravity of this office. Exercise your function as independent judges committed solely to the law and accountable only to God and your own conscience.

In this expectation, I now ask you to pledge yourselves to perform your duties faithfully by swearing a solemn oath:

I swear, so help me God!

You will swear by God the omnipotent and omniscient to remain faithful to Volk and Vaterland, to abide by the constitution and laws of the land, to carry out your official duties conscientiously and to faithfully exercise your function as judges of the Volksgerichtshof and dispense judgement in all conscience.

A speech full of pathos and which received lengthy applause from the audience in the chamber. They too, were seized by the ‘solemn gravity’ of the occasion, and their expressions revealed pride. Were they not witnessing the birth of a new and unique court of justice? This court was endowed by the law of 24 April with all powers formerly held solely by the Reichsgericht, the Imperial Court of Justice, the power to judge such crimes as high treason, treason, attacks on the Reichspräsident, particularly serious damage to military resources and the murder or attempted murder of members of the government of the Reich or state governments. The guests at the opening ceremony fully appreciated that such a court was urgently needed at that moment, in a time of change on a national level, no matter how the international press might rail against it, claiming that it was a summary court. For Gürtner, the outraged protests from the press abroad could only be the result of ‘either unfortunate ignorance of the procedural stipulations for the Volksgerichtshof and a lack of understanding of the German sense of justice or malicious intent to stamp on any attempt to create a new Germany’.

In fact – and Gürtner was perfectly aware of this – the new Volksgerichtshof was legally a special tribunal. As the interim President, Gürtner inaugurated the longest-serving of the three senate presidents, Dr Fritz Rehn, as the new Judge-President. As a ‘man of the first hour’, Rehn was a particularly apt choice for the position. Former chairman of the special court in the district court of Berlin, he had gained adequate experience with Nazi legal practice and had proved that the National Socialists could rely on him. The new regime had already set up the first extraordinary courts on 21 March 1933. In such courts, the accused appeared not before local judges well-versed in specific legal areas, but hand-picked NS jurists. The ‘Decree of the Reich Government on the Establishment of Special Courts’ made short work of the process of trying defendants: the period of notice was three days and could be reduced to twenty-four hours. Moreover, the decree abolished other cornerstones of the due process of law: it states clearly ‘There will be no oral hearing on the warrant of arrest’. This laid the system wide open to arbitrary dispensation of justice, wrongful convictions, and excessive and cruel punishments – even murder in the name of the law. Rehn had performed his tasks to the full satisfaction of the new regime. And now he was being rewarded – for reasons of legal status only on a provisional basis – with the title of President of the highest extraordinary court, a meteoric rise for the ambitious jurist.

Rehn was assisted by Wilhelm Bruner, senate president from Munich – just a few months later, after Rehn’s death on 18 September 1934, Bruner took over as executive Volksgerichtshof President and remained in office until 1936 – and Eduard Springmann, senate president from Düsseldorf. They were joined by nine other professional judges. Four of the ‘honorary’ associate judges, the other five being high-ranking members of the army, came from the Ministry of the Reichswehr. The remaining eleven members of the court represented the various NS organizations. Everyone wanted – and would have – their role to play in this new court.

The day before the opening ceremony, the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung had informed its readers of the appointment of the judges and the requirements. The author commented approvingly that: ‘The judges of the court have been appointed with special regard to the appointment of personages with extensive knowledge of criminal law, with political foresight and vast experience.’

Altogether, the initial staffing list of the court comprised eighty employees. This meant that the Volksgerichtshof was still far smaller than the Reichsgericht, and its organizational structure was by no means ideal from the point of view of its keenest advocates. The new court was separate from the Reichsgericht, but initially, the prosecution counsel still came from a branch office of the Reichsanwaltschaft (Reich prosecutor’s office), which was based in Leipzig. The head of this branch office was Reichsanwalt Paul Jorns, a jurist who had worked on cases of high treason during the Weimar Republic and proved himself a loyal servant of the regime as investigator in the case of the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in 1919. He was assisted by senior prosecutors Wilhelm Eichler and Heinrich Parrisius, who one year before, together with Oberreichsanwalt Karl Werner, had conducted the preliminary investigations against the alleged perpetrators of the Reichstag Fire and who was one of the prosecutors in the subsequent trial.

These were all seasoned lawyers and committed to ‘the German cause’. The Nazi leaders expected consistent and harsh dispensation of justice, and these men would ensure that they would get it. In its edition of 15 July 1934, the Völkischer Beobachter revealed what could be expected of the ‘new German judicature’ and the Volksgerichtshof. In bold terms, a commentator anticipated the end of the era of ‘liberal criminal law’ and enlightened his readers:

Since Germany achieved political union and eradicated the manifestations of an outdated and diseased age, political crime and political offences must be seen in a different light. We do not need to rethink our idea of criminal law in itself in order to see that a special court is required for the crimes of treason and high treason – new circumstances create new requirements: the political unity of the German people, purchased with the blood of thousands, cries out to be defended. And in the Volksgerichtshof, it has found a defence against the traitor, the saboteur, against negating elements from within.

He continued:

Anyone who turns against the political unity of the National Socialist state today will be judged by this court. The disastrous trial of the Reichstag arsonists is still fresh in our memory. Despite the blatantly political motivation behind the crime, it dragged on for months, delayed by politically inexperienced judges who, in order to reach an ‘objective judgement’, again and again called for fresh testimony from experts, questioned countless witnesses and nevertheless produced a miscarriage of justice. This in particular makes the need for politically trained expert judges obvious.

Historically speaking, the Volksgerichtshof, which convenes for the first time today and is intended to be a permanent institution, therefore represents something completely new within the German legal system. It marks the end of an inglorious chapter in the history of German justice, an era in which politically and criminologically insensitive German legal authorities were so intent on objectivity and loyalty to the constitution that they were unable or unwilling to see what was happening around them.

And the opinion of this commentator in the official Nazi Party newspaper was not only shared by staunch supporters of the NSDAP. Judges of a nationalist-conservative persuasion, still convinced of their ‘judicial independence’, could also identify with it. Were the objectives not the rebirth of the German nation and to ward off danger to the people, the Fatherland and the Führer? And had the arson attack on the Reichstag building not clearly shown that the Communist threat had by no means been averted? And the protracted trial of the arsonists had surely demonstrated the need for a court with the power to take more decisive and consistent action against the enemies of the people and their puppet masters?

Indeed, the National Socialist rulers had been infuriated by the course and outcome of the Reichstag Fire trial. In the end, four of the five defendants were pronounced not guilty, though to the Nazis, they were no less than Communist subversives. Not merely a defeat for the German legal system, but a scandal …

In the late evening of 27 February 1933, fire broke out in the building of the German Reichstag. For the National Socialists, who had come to power just a few days previously, this was proof that the Communists were in no way willing to accept the new political situation. The Nazis were convinced that it was the work of arsonists and a signal that a revolution was imminent. Would there now be an armed Communist uprising?

That same night, a Dutch travelling journeyman was arrested at the scene of the fire. His name: Marinus van der Lubbe. But had he been acting alone? Was he a lone arsonist with no accomplices and not following anyone’s orders? For the Nazis, there could be no doubt: this was the work of the Communists …

On 30 January, the very day on which the Nazis seized power, not only Minister for Trade and Industry Alfred Hugenberg but also Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick and Hermann Göring had pushed for a ban on the Communist Party (KPD). Hitler, however, was against it – for the time being. He was afraid that a ban would provoke serious inner-political conflict and strikes, which would not have served his purposes in view of the upcoming election.

Now, however, after the Reichstag Fire, he was forced to take action. Just one day after the fire, on 28 February 1933, Hitler had signed two emergency decrees: the ‘Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the People and State’ and the ‘Decree of the Reich President against Treason against the German People and Actions of High Treason’. Their most controversial content: the introduction of ‘Schutzhaft’ (protective custody) and the suspension of basic rights granted under the Weimar Constitution. Thousands were arrested soon after – mostly KPD party functionaries, but also social democrats and trade unionists. Hitler now had the legal basis for dealing with his political opponents once and for all.

Meanwhile, the investigations into the Reichstag Fire were in full swing. The Nazis seized the psychologically opportune moment to throw their propaganda machine into action, conjuring up the image of a Communist threat everywhere. As one individual acting alone, van der Lubbe did not fit their scenario. The puppet masters, the real perpetrators behind the arson attack – the ‘agents of world communism’ – had to be identified and convicted.

And the tireless investigators found what they were looking for: Ernst Torgler, Chairman of the KPD faction in the Reichstag, was arrested after turning himself in to the police in order to prove his innocence when he learned that he was a suspect, having been one of the last persons to leave the building before the fire was discovered. And three Bulgarian emigrants – Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoy Popov and Vassil Tanev – were also arrested after witnesses reported seeing them at the scene of the fire.

On 24 April 1933, following the preliminary examination, Oberreichsanwalt Werner indicted the three Bulgarians, van der Lubbe and Torgler on charges of high treason and arson. Not long before, on 29 March 1933, the Nazis had hurriedly pushed through the ‘Law on the Imposition and Execution of Capital Punishment’, already presaged in the ‘Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the People and State’, authorizing the imposition of the death sentence with retroactive effect for certain serious crimes committed between 1 January 1933 and 28 February 1933. This made it possible to demand the death sentence for the defendants in the Reichstag Fire case.

The trial against the five defendants opened on 21 September 1933 before the Reichsgericht. Only one of the accused, Ernst Torgler, chose a defence counsel, Berlin lawyer Alfons Sack, who is said to have sympathized with the NSDAP. The others had to place their trust in court-appointed counsel. The main hearing lasted several months. However, the evidence presented produced no new insights into a possible Communist conspiracy. Not even the reward of 20,000 Reichsmarks, offered by the police shortly before the beginning of the trial, brought any results.

Instead, as German citizens became disillusioned with the course of the eagerly-anticipated trial, a rumour that the Nazis had set the fire in the Reichstag themselves for propaganda purposes began to gain ground.

At last, shortly before Christmas, on 23 December 1933, the court finally reached a verdict. Van der Lubbe was sentenced to death and to ‘perpetual loss of honour for high treason, seditious arson and attempted common arson’. Surprisingly, the other four defendants were pronounced not guilty.

In summing up the grounds for the decision, the court stated that van der Lubbe’s death sentence was justified because the Reichstag Fire had been a political act. The court also stated that in the spring of 1933, the German people faced the threat of world Communism and stood on the brink of chaos. The arson attack, it said, was the work of the Communists, whose perfidious plans van der Lubbe had carried out. In giving the reasons for its decision, the criminal division also made mention of defamatory claims that the National Socialists had laid the fire in the Reichstag themselves. These absurd and malicious allegations had been spread by ‘expatriated rogues’ and their lies had been completely refuted in the course of the trial, the chairman stated in a piercing voice.

And yet: the National Socialists, who had accompanied the trial with clamorous propaganda and had high hopes of its outcome, were indignant and angered by the verdict.

The journal Deutsches Recht, the central organ of the Bund Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Juristen (BNSDJ – Association of National Socialist German Legal Professionals) commen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Foreword The Presence of the Past

- Prologue A Death Sentence, or The Second Career of Roland Freisler

- Chapter 1 The Ceremony

- Chapter 2 The Lawyer from Kassel

- Chapter 3 One Volk, One Reich, One Führer – and One Judiciary

- Chapter 4 Undersecretary and Publicist

- Chapter 5 Against Traitors and Parasites

- Chapter 6 The Political Soldier

- Chapter 7 In the Name of the Volk

- Chapter 8 The 20 July Plot

- Chapter 9 The End

- Chapter 10 No ‘Stunde Null’

- Appendix I The Life of Roland Freisler

- Appendix II The Volksgerichtshof Judges and Lawyers

- List of Sources and Annotations

- Bibliography

- Plate section