- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

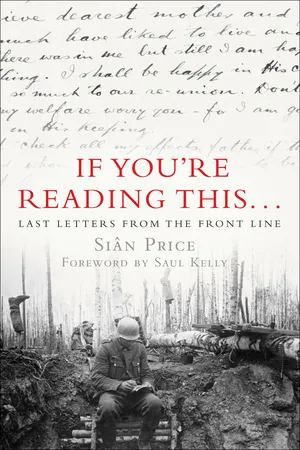

Three centuries of war. Three centuries of sacrifice. "Tales of love and heroism from conflicts such as the Napoleonic Wars and Afghanistan today." —

The Mirror

In this brilliant and profoundly moving collection of farewell letters written by servicemen and women to their loved ones, Siân Price offers a remarkable insight into the hearts and minds of some of the soldiers, sailors and airmen of the past three hundred years.

Each letter provides an enduring snapshot of an impossible moment in time when an individual stares death squarely in the face. Some were written or dictated as the person lay mortally wounded; many were written on the eve of a great charge or battle; others were written by soldiers who experienced premonitions of their death, or by kamikaze pilots and condemned prisoners. They write of the grim realities of battle, of daily hardships, of unquestioning patriotism or bitter regrets, of religious fervor or political disillusionment, of unrelenting optimism or sinking morale and above all, they write of their love for their family and the desire to return to them one day.

Be it an epitaph dictated on a Napoleonic battlefield, a staunch, unsentimental letter written by a Victorian officer, or an email from a soldier in modern day Afghanistan, these voices speak eloquently and forcefully of the tragedy of war and answer that fundamental human need to say goodbye.

"The poignant farewells encapsulate the final words of servicemen to their loved ones before they were killed in action." — The Telegraph

"A timely reminder of the tremendous sacrifices made by fighting men and women of all countries in all ages." —Military History Monthly

In this brilliant and profoundly moving collection of farewell letters written by servicemen and women to their loved ones, Siân Price offers a remarkable insight into the hearts and minds of some of the soldiers, sailors and airmen of the past three hundred years.

Each letter provides an enduring snapshot of an impossible moment in time when an individual stares death squarely in the face. Some were written or dictated as the person lay mortally wounded; many were written on the eve of a great charge or battle; others were written by soldiers who experienced premonitions of their death, or by kamikaze pilots and condemned prisoners. They write of the grim realities of battle, of daily hardships, of unquestioning patriotism or bitter regrets, of religious fervor or political disillusionment, of unrelenting optimism or sinking morale and above all, they write of their love for their family and the desire to return to them one day.

Be it an epitaph dictated on a Napoleonic battlefield, a staunch, unsentimental letter written by a Victorian officer, or an email from a soldier in modern day Afghanistan, these voices speak eloquently and forcefully of the tragedy of war and answer that fundamental human need to say goodbye.

"The poignant farewells encapsulate the final words of servicemen to their loved ones before they were killed in action." — The Telegraph

"A timely reminder of the tremendous sacrifices made by fighting men and women of all countries in all ages." —Military History Monthly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access If You're Reading This . . . by Siân Price in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AT WAR WITH FRANCE

I only send these few lines written according to Your desire in hurry & confusion to assure You that in spite of Your forgetfulness, my affection for You is as strong as ever, & that if a cannon ball hits me tomorrow I believe I shall die thinking of you.1

BETWEEN 1793 AND 1815, Britain was Napoleon’s fiercest opponent on land and sea. He had declared he must ‘destroy the English monarchy’2 and claim the island nation as French territory. This was no sustained battle. The French Revolution of 1789 was the touch-paper that sparked the revolutionary wars of 1793 to 1802. Temporary peace following the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 was cause for celebration, but did not last. Between 1803 and 1805 Britain was under constant threat of French assault. The Peninsular War began with the French invasion of Spain in 1807, and lasted until 1814. There then followed the Hundred Days of 1815 when Napoleon escaped from exile in Elba. Battles such as Trafalgar, Badajoz, Vimeiro and Waterloo became – and remain – etched in the public consciousness for their immense loss of life and sheer, chaotic bloodiness. It was a period of distinctly mobile warfare as Britain and ever-changing coalitions fought to stave off Napoleon’s self-proclaimed desire to ‘rule the world’.3 This was fighting on an unprecedented scale, across Europe, South America, the Caribbean and the East Indies.

France under Napoleon was in pursuit of expansion and conquest rather than peace. Achieving a French European order was seen as a progressive self-affirmation for the country and Napoleon revelled in the glory of battle to achieve what he believed to be the greater good for the world. In short, there was a culture of war running through this period, as unbridled battle bred more battles, and victory bred avarice.

In 1793, the British Army was 15,000 strong at home, with a further 30,000 troops abroad. Bills were passed to raise a further 25,000 soldiers and 19,000 militia,4 as well as drafting in troops from Hanover. By the time of the Napoleonic wars, one in ten British men was in the army, and boys as young as eight could be found on board ships. Conscription was never introduced in this period; ordinary recruits were drawn from army and militia volunteers, and raised by navy press gangs and recruitment posters that promised that ‘bringers of good recruits will receive three guineas reward’.5 By 1811, the combined army and naval strength was in the region of 640,000 men, with almost continual recruitment due to the incredibly high death tolls.

In Britain, the upper ranks of navy and army were largely made up of upper- or middle-class men, including a large number of sons of clergymen and solicitors. Many bought their commissions into regiments and used their family connections to further their career and bolster their pay. According to the letters and accounts that survive – albeit largely from the literate officer ranks – this class difference did not make for overly soured relations. After all, they were fighting together to defeat the enemy, and skilled officers would wield a sword as quickly as the privates. The archetypal image of the drunken, ill-organised and poorly trained common soldier was certainly true to some degree, but harsh discipline kept men largely in check. Lieutenant Woodberry wrote, ‘no one can detest corporal punishment more than I but – subordination must be kept up or we shall all soon go to the dogs.’6 We should not forget, of course, that when the call came to spring into action, these men were the workhorses of the war machine. Countless gave their lives to the cause. Training and weaponry varied in quality over this long period and many men learned the art of hand-to-hand combat in the arena of real war.

In spring 1798, a French army massed on the Channel coast, sparking very real fears in Britain of an invasion. The thought of the imperial eagle decorating the spires and bastions of British identity led to a genuine ‘great terror’. Histrionic posters compared the French to ‘spiders’ who would ‘weave a web around their victim’, and painted them as murderous pillagers and rapists who would stop at nothing to stake their claim. A poster in the West Wales port of Fishguard asked, ‘Will you, my Countrymen, while you can draw a trigger, or handle a pike, suffer your daughters, your sisters, and wives, to fall into the power of such monsters?’7 The menace galvanised people and Parliament into action: defensive fortresses were built along the coasts and reserve corps raised. In the event, the threatened invasion was something of a damp squib, but Britain was united in a common cause against this ‘Corsican scoundrel’. He and his threat became an inspiration for caricatures, songs, plays and poetry. Anti-Napoleon ditties flooded the newspapers: ‘Buonaparte, the Bully, resolves to come over . . . From a Corsican Dunghill this fungus did spring . . .’8

On a serious note, fear penetrated the national psyche. This was to be a war to the death against a formidable opponent. With a photographic memory and tremendous work ethic, Napoleon often worked eighteen hours a day, handling and digesting masses of complex information. He was confident, ambitious and styled himself as a conqueror complete with Romanesque laurel wreath crown.

In 1801, Britain and the Ottomans forced the French to surrender in Egypt, and the 1802 Treaty of Amiens signalled an end to hostilities between France and Britain. This short-lived peace brought temporary respite and relief to many men who had been away from home for months – even years. Rear-Admiral Collingwood wrote home, relieved that ‘the hope of returning to my family, and living in quiet and comfort amongst those I love, fills my heart with gladness.’9

Trafalgar in 1805 was Britain’s most emphatic naval victory: a demonstration of tactical splendour and derring-do. Twenty-seven ships defeated thirty-three French and Spanish ships off the coast of Spain without the loss of a single British vessel. Battles fought over the years following Trafalgar shaped the face of Europe and its constitutions for decades to come. Wellington and Nelson emerged as iconic names from battles on land and sea. Napoleon’s audacious escape from imprisonment on Elba in February 1815 was a final attempt to engage in glorious war once again. It culminated in perhaps the most famous battle in European history at Waterloo. Napoleon and his desire for French imperial domination was snuffed out for good.

In more than twenty-two years of intermittent battle, over one million French people were killed, and the death toll for the rest of Europe was estimated to be as high as five million. The Marquis d’Argenson, France’s foreign minister, aptly proclaimed, ‘Triumph is the most beautiful thing in the world . . . but its foundation is human blood, and shreds of human flesh.’10

LEAVING FOR WAR: EMOTIONAL AND JOYOUS FAREWELLS

For the men leaving for war throughout this period, the overwhelming sentiment was one of excitement, patriotism and happiness, although for those left behind, wrote Lieutenant John Hildebrand, there was ‘less enthusiasm in the female breast’.11 Some wives were able to travel with their husbands, while others tearfully waved them off from ports, having given them good luck charms, locks of hair and miniatures. Many of these men would never have left Britain before and went cheerfully into the unknown. Joseph Coates wrote, ‘Oh with what pleasure did I leave – little thinking or even caring what befell me, only of seeing strange places and fresh faces.’12 Encountering new peoples, cultures and languages was an attractive by-product of far-flung conflict, as one soldier wrote about his experiences in Copenhagen: ‘the lower order of people are very ugly but very clean, there is some very pretty women, they have a genteel air with them which you don’t find everywhere.’13

There was a faint trace of nerves in some early correspondence, although men tried to dampen such thoughts in letters home. Captain John Lucie Blackman regarded his fate – whatever that might be – as ‘la fortune de guerre’.14 Gunner Andrew Philips wrote in 1804, ‘Dear Father & Mother . . . I am sore afraid that we will never see one another again,’15 and J.O. Hewes informed his father in 1807, ‘We have cleared away for action and is ready at a minute’s warning to put to sea. It is expected to be a very severe action.’16 Men largely relished the opportunity to make a contribution and display their mettle: ‘This, my dear parents, is the happiest day of my life; and I hope, if I come where there is an opportunity of showing courage, your son will not disgrace the name of a British soldier,’17 wrote George Simmons. Regardless of nationality, those left behind faced an anxious wait for the fate of their loved ones. Mademoiselle de Touche wrote to Duke Fitzjames, ‘Return, dearest, I beg thee. I await thee . . . Adieu my dearest, do not forsake me. I embrace thee with all my heart.’18

UNDIMMED PATRIOTISM: TOTAL BELIEF IN THE CAUSE

Literacy was poor among the rank and file,19 but officers’ accounts and the small number of letters surviving from the lower ranks are testament to an unabashed patriotism and belief in the cause the men were fighting, buoyed by stirring speeches from their officers – who undoubtedly believed every proclamation they made. Newspapers and bulletins whipped up a jingoistic frenzy that the campaigns were ‘the cause of England – the cause of civilized Europe, and of all the World’. News of each ‘glorious’ victory was splashed onto posters and front pages with cries of ‘Huzza my Boys’ and accounts of how they ‘drubb’d the enemy’. As soon as reports came in, they were hurriedly printed – emphasising the numbers killed. ‘Great News in Spain,’ read one, ‘. . . I am just from Spain. Dupont and Twenty Thousand Men ARE TAKEN.’20

Just as the British public lapped up news from overseas, letters home were equally brimming with patriotic conviction. Major-General Sir William Ponsonby wrote home days before Waterloo: ‘There seems to be in England a decided feeling of war & perfect confidence as to the successful result . . . Bonaparte will certainly have need of all his extraordinary abilities to resist the immense force about to attack him.’21 Years earlier, William Thornton Keep had similar convictions: ‘Bonaparte is now to fall or never. The combined efforts of his enemies are destined to crush him. But if he escapes, the consequences will be dreadful to England and the other nations of Europe.’22 Even European dignitaries were united in their anti-Napoleonic sentiment. Letters betraying any trepidation at Napoleon’s force were few and far between. Francis D’Oyly admitted to his mother, ‘Me and you are the only two . . . who appear to think that we shall not speedily upset Napoleon.’23

Patriotism was flourishing among French ranks too. One soldier wrote home, determined to fight to the death – ‘it is important that military and maritime present a movement and show of infinite uniforms’ – describing the battle as akin to ‘la chasse’ (the hunt).24

A SOLDIER’S LOT: DAILY SLOG AND HARDSHIPS

‘I have been this three years at sea and ’as not ’ad my foot on shore,’25 grumbled John Wilkinson. This period of warfare kept men away from home for months on end and it was no surprise that there was frustration with their lifestyles – particularly among the lower ranks who could not ask family at home for money to buy extra blankets, clothes and boots to replace the ones that had fallen apart.

Living conditions varied according to rank but the mobile nature of conflict meant men were often sleeping in shared beds, in sodden and muddy pitched tents or wherever they could find shelter. One soldier in Malta in 1810 described his bed as three boards on top of two trestles, with a dead cat under the overhead floorboards dropping maggots into his face during the night.26 In the navy, lower ranks slept between the guns, in hammocks or on tables; they were, though, at least assured of regular meals (and beer), fruit, and prompt medical attention. For soldiers, food was rationed, basic and often meagre – small wonder many men turned to theft to quiet their rumbling bellies. It was a tough, unremitting way of life only made bearable by the strong camaraderie between men, forged through shared experience. The regiment became an erstwhile family.

During this period, as well as the mortal risks that came with each battle, the men faced rampant disease. Outbreaks of ‘Walcheren fever’27 in the early 1800s killed thousands of men, and plagued others for decades to come. Crowded, dirty, makeshift camps meant outbreaks of diarrhoea, and typhoid (which was sweeping Central Europe in 1813 anyway) spread easily, with devastating effect. It was estimated that for every soldier killed on the battlefield, four would die from disease.

Pay at this time would have been around two shillings and four pence per day28 for a corporal and even lower for privates. However, it was more than many men could earn at home, and military service at least came with a pension. Wages were often in arrears, though, and many men relied on home for extra provisions. In the navy, pay was a little more regular and the capture of an enemy ship brought prize money that was shared out among the entire crew.

Men could be awake and active for days at a time. Corporal Joseph Coates wrote home after three days of non-stop fighting and marching. ‘What I [would] have given for a few hours rest but in vain, no rest, but fighting. Marching and Fatigue was our lot, but in the mi...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- AUTHOR’S NOTE

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 - AT WAR WITH FRANCE

- 2 - THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

- 3 - THE ANGLO-ZULU WAR

- 4 - THE BOER WAR

- 5 - THE GREAT WAR

- 6 - THE SECOND WORLD WAR

- 7 - THE FALKLANDS CONFLICT

- 8 - CONFLICTS IN IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN

- PICTURE CREDITS FOR PLATES

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX