- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

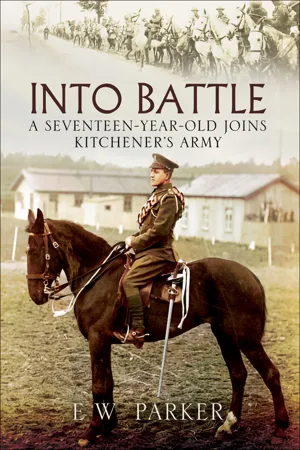

Written well over ninety years ago while the experiences of youth were still fresh in the authors mind, this is the story of a seventeen-year-old boy from the time he joined Kitcheners Army, as one of the first hundred thousand in 1914, until he found himself in hospital—an officer with the Military Cross—recovering from his last wound, on the day of the Armistice, 11 November, 1918.In no way a formal record of the great and terrible events it describes, this is a purely personal, almost private, account. It is a plain, unvarnished tale—and even more effective for that—of heroism, and the horror peculiar to trench warfare of the First World War.Interspersed with moments of pity, humor and a deep response to natural beauty and peace out of the firing line, it is a record, which in its details, direct simplicity and manner of telling, comes nearer to the truth than many more ambitious accounts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Into Battle by E.W. Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

I Join the 15th Hussars

On the night of I September 1914, when I enlisted in Kitchener’s Army, the War of 1914-18 was barely a month old and my eighteenth birthday was just approaching. I was far from being the youngest recruit, for in the queue was a boy of fifteen who lost his life on the Somme a couple of years later.

It took several hours before my turn came round and then I had to line up again to give my age as nineteen before I was finally accepted and given the order to report at the barracks on the following morning. For a couple of weeks I had been thinking seriously of joining up, and one by one my friends had already enlisted by the time I had decided where I thought my duty lay. All those young men were conscious of the threat to their country from the might of the Kaiser’s Germany with its millions of well-trained conscripts, and it was general knowledge that our own small regular army, together with the territorials, would need every man who could bear arms if Britain was to survive. So although the army life did not appeal to me I took the plunge at last.

I was now a man under orders. The irrevocable step had been taken and, after getting my papers signed at the barracks, I dismissed my forebodings and set off for Bristol with a strange feeling of elation. I was doing the right thing and everything would turn out well – that reflection was to be my standby for the next four years.

When I was seated in the Bristol train at Paddington my fellow passenger, a middle-aged man, got into conversation with me and soon discovered my mission. He said cheerfully, ‘The Army makes or mars’, and left me wondering which my own fate would be. Luckily by the time I had passed through the gates of the cavalry barracks at Horfield I had forgotten my travelling companion’s words or I should have imagined that I had already discovered which way the army would affect me.

That night when I wrapped myself in a brown blanket and stretched my limbs on the dew-saturated grass my worst fears seemed about to be realized. All around were thousands of recruits, yarning and making jokes into the early hours of the morning. Beneath the bright September stars I tossed restlessly from side to side to ease my projecting hips which pressed into the stones embedded in the grass. Far into the night the babel of voices rose and fell while I listened to the strange tales and queer outlandish speech of men drawn from all parts of the British Isles.

With the dawn the most restless threw off their blankets and began to look for water. When we discovered a tap we had to queue up to share the one piece of soap we could muster between us, and long before I was drying my face with a pocket handkerchief the whole camp was astir and men were walking up and down to get the circulation back to stiffened limbs.

Soon there were signs that our usual breakfast-time had arrived. Sharp eyes kept scanning the door of the cookhouse and when hours later a line of buckets glinted in that direc tion everyone was afoot and each orderly was surrounded by a struggling mob of untidy, unshaven men. I didn’t have a chance in that scramble and, more or less a spectator, I watched the lucky owners of mess tins making for safety out of the crowd. More often than not they lost the contents of their tins on the way! When the bread ration followed, that, too, went to the strong, some of whom found it possible to get two or more shares which they wolfed ravenously. When breakfast was over there was nothing to do but walk about. Fortunately I soon discovered a canteen and there I tasted food for the first time since leaving home.

In the afternoon we fell in on parade and afterwards, in some semblance of military formation, marched through the gates of the barracks into the streets of Bristol, there forming a long column of fours that presently wound its way across the open fields of the Downs. Here we halted to suffer the boredom of idling while thousands of names were called over. At long last the monotonous, droning voice fell silent and we went swinging along to the railway station to begin a night journey in a direction unknown to any of us. Towards midnight our railway carriages were exchanged for small open trucks in which we were jolted slowly through a beau tiful, but unfamiliar, countryside where from the spikes of the fir trees glittering dewpoints reflected the brilliance of the September stars. Feeling bitterly cold, but buoyed up with the spirit of adventure, we laughed heartily when the inevitable wag announced that ‘they were sending us to Siberia’, for it seemed literally true.

Nobody could guess where the journey would end and when at three o’clock in the morning we arrived at Long-moor in Hampshire all that could be seen were the roofs of a few army huts emerging bleakly above the sea of thick white mist. These huts were not for us; instead we were offered the open fields and one blanket apiece in which to curl up with the damp grass moistening our cheeks.

With the rise of the sun we gladly gave up the vain pursuit of sleep to meditate anxiously on the prospect of rations. With determination born of hunger, I waited in the crowd surrounding one of the tea buckets until the supply was exhausted. Then, like many more of my new comrades, I realized that I must go without.

As the sun mounted higher on this beautiful September morning the lack of food and sleep had its effect so that I felt faint and wondered bitterly if I should ever adjust myself to my new life. We spent the early morning in idleness looking on while a party of men under a sergeant began erecting bell tents. After we had watched with growing interest our turn came to take part in the work, and by the time the guy ropes of our own tent had been tightened, hundreds of white cones had sprung up, surrounding us with a still rapidly growing canvas town. Each tent in this encampment was to be the home of twenty men for the next month or so.

It would have been difficult even in Kitchener’s Army to have found a tougher crowd than the owners of the forty feet that at sundown kicked their way towards the pole in the centre of our tent. Frequently during the night the tent flap was raised so that my head could be poked underneath to breathe the pure night air outside!

During the whole of September rations were of the scantiest. Tea buckets lacked milk and sugar, and though the bread ration came regularly we had to eat it without butter. At breakfast-time minute scraps of fat ham rewarded us on our return from early-morning stables. At last when a crowd assembled outside the Quartermaster’s Stores several officers hurried to the spot to listen tactfully to a long string of grievances which they immediately promised to put right. From that day onwards there was a general improvement in the rations. What had happened to our food during the previous month is a mystery which has never been solved.

After living in the overcrowded tent for nearly two months, our little community of twenty men had learnt to live together in mutual friendliness in a way that would have seemed impossible at first. I was the butt of a group of Eastenders and I had to stand up for myself. Although no boxer, I managed to come off fairly satisfactorily when attacked.

Now with Winter in sight we moved into the mounted infantry huts which had been erected in the Boer War. In these comfortable quarters, with their pervasive odour of paraffin, I found myself among an entirely different group of men, more miscellaneous in calling and origin and much more pleasant as companions. One of them, however, was a peculiar character who suffered from incurable melancholy. One night when I had settled down in my bed he began muttering that he would have to end his life. This in itself was nothing new, but when I saw him draw out his razor I leapt out of bed, snatched it from him and flung it out of the window. On this the poor fellow accepted the position and weakly got into bed.

Another strange type was a young fellow from a reforma tory who was constantly asking someone to punch him. That, of course, was something no one could do in cold blood, but if one clenched a fist, pretending to comply with this strange request, he would immediately fall down with a crash on the hard wooden floor and then get up smiling and happy at having shown off a trick he had learnt as part of his own special sort of education.

In my leisure time I tried to polish up my German, and when I heard of some evening French classes I turned up at the Army School where the band boys attended compulsorily. One evening only one of them was present and I learnt from him that all the rest had deserted. They were found a few weeks later working in the Bristol area. They were thrilled to think that in the outside world there was now a clamorous demand for the services of youngsters under military age.

Every evening while I was at Longmoor I paid a visit to the Soldiers’ Home, where for fourpence, the price of twenty cigarettes, I could obtain a huge basin of porridge floating in milk. The old soldiers would have scorned such food, but for a teenager with a never-satisfied appetite this was just what was most needed after a hard day’s work.

Cavalry life began at dawn, when we all turned out to parade for stables. Here we learnt the art of grooming restive horses, a task which helped us to anticipate the sort of difficulties we should meet when we had to ride them. It was several months before we could count on two rides a week; but in the meantime, when luck came our way, we went back to our less fortunate comrades with stories of quite unbroken remounts successfully gripped between our trembling knees.

Reports of this nature considerably increased my respect for the livelier animals in our collection, and when one morning it was my turn to take a particularly malicious black mare for squadron drill I was not at all enthusiastic, to say the least. My knees lacked grip, and until the black mare broke into a delicate, effortless trot I did not know what to expect. Then it seemed as if those dainty, spindle-like legs trod upon air instead of the much-trampled earth of the parade ground. Never before had riding been so comfortable, but I warily slackened the reins and remembered to keep my spurs clear of her sides as we cantered in fours on to the plain alongside the other troops of the squadron.

Advancing on the trumpet call ‘Walk march!’ we quickly broke into a trot, followed by a canter, with our drawn and pointed swords flashing in a long line across the plain. Sounding above the jingling of harness and the clattering rattle of our empty scabbards, we heard the thrilling notes of the call to charge. Away we went, steadily at first, each horse accelerating as its reserves of strength allowed. Soon I was abreast of our squadron commander whose furious red face, turning in my direction, was convulsed in anger. In a trice he was outpaced and left so far behind that his raucous voice could no longer be heard. Then, as happened on great occasions subsequently, my spirits rose and with my young heart galloping in time with the racing feet of my splendid mount, I found myself leading the charge.

Now ‘Retreat’ was sounded by the trumpeter, and at last the little black mare made terms, and we returned to overtake the squadron in full retreat. Rejoining its bunched ranks we were welcomed by viciously raised hooves, but despite such malice we squeezed through so violently that we arrived once more in a leading position on the other side.

At this point the little mare made a bid for freedom. In a sudden frenzy she reared up and toppled over sideways, pinning me to the ground. Luckily, before she could get up I seized the reins and so held her down long enough for two troopers to gallop up and save me from being dragged at her heels.

One fine Spring morning in 1915 we set off in pairs on a Point and Compass race. It was one of my lucky days, for beneath me cantered the same little black mare in a tho roughly good temper. Before long my companion was hopelessly outdistanced and, easing to a canter, we sped across the Hampshire Downs and saw scattered on the tops of the hills small round copses of trees standing out against the skyline, marking the buried bones of some bygone race of warriors, and helping a younger generation to find their way by map and compass.

Taking every jump that offered, I came at last to a country lane where I drew up to await my companion. When he overtook me I again forged ahead until confronted by a strong, five-barred gate. Intending to dismount, I took my right foot out of the stirrup and felt the plucky little mare brace her muscles to fly smoothly over the top-most bar. As she landed softly, I realized with surprise that I was still in the saddle.

When the routine of Longmoor Camp had at last been organized, the life led by the cavalry recruits grew more strenuous. At dawn we paraded for the stables ‘to water your horses and give them some corn’. After breakfast we went riding and returned before lunch to groom and feed our chargers. About two o’clock everybody except the old soldiers turned out for foot drill, and on the parade ground small groups of men performed under their N.C.O.s an astonishing variety of exercises. One squad of men with drawn swords lunged with assumed ferocity towards a neighbouring group of men who marched and wheeled in a bewildering pattern of cavalry movements; others were mastering the mysteries of musketry or succumbing to the boredom of rifle drill; while in the distance we could have heard, had we kept silence for a few minutes, the powerful snoring in chorus of the ‘old sweats’ who had contemptuously turned into their bunks after midday dinner.

Occasionally this daily cycle of duties was interrupted when we were detailed for Guard Duty. On these occasions we ‘rookies’ were obliged to borrow the khaki uniform of an old soldier and then for twenty-four hours we could imagine that we were real soldiers. This gave us the thrill of adventure, and after undergoing the ordeal of inspection by the Adjutant we looked forward to our turn of sentry duty with the feelings of men about to fight their first battle. Apart from the prospect of catching a spy red-handed, which always seemed worth bearing in mind, we knew that inside the Guard Room, and entrusted to our sole care, were several desperadoes whose military crimes might be augmented at any moment by a desperate bid for freedom. It was well that inquisitive officers did not often test our vigilance, for with such possibilities in our minds we were ready to shoot at sight.

The Water Guard was not taken so seriously, although we were impressed by the fact that it was a rather vulnerable place, and that on any night an attempt to poison the whole camp might have to be frustrated by the determined use of our rifles. Half-way through the night our ardour usually cooled off, and now and then we stealthily puffed cigarettes while maintaining a sharp look-out for the approach of the visiting rounds.

The hours spent in this pleasant spot were not altogether wasted. We grew fond of the deep pool in which the surrounding hills, with their thickly wooded slopes, were reflected in crystal clear water. In April 1915 we began to swim there on the holiday afternoons when the old cavalrymen enjoyed their privilege of sleep.

About this time we discovered that over the hills a company of R.E.s were constructing a narrow-gauge railway. One evening when we visited the spot we found it deserted. The railway lines had been completed and lying on its side near by was a small flat-topped truck. This we lifted on to the rails and laboriously pushed to the crest of the hill where we loaded ourselves toboggan-fashion on to its flattop. Then off we started downhill, gathering speed until the air whistled through our ears, and the wheels tore along the tracks. By the time news of this discovery had spread throughout the camp there was a nasty accident, and a notice in Battalion Orders placed our switch-back railway out of bounds.

One day when the men of the 15th and 19th Hussars Cavalry Reserve Regiment were still wearing red tunics, blue trousers, khaki caps without badges, and the civilian boots in which they had enlisted, our acting Squadron Commander, Captain Dalgetty, paraded us to say that we were to hold ourselves in readiness to repel a threatened German attack at Scarborough, for the town had been bombarded from the sea. Although we ourselves heard no more of this false alarm, I learnt years later from one of the Lovat Scouts that they had been hurried to the threatened area and were, in fact, the cause of the delightful rumour that thousands of Russians were arriving in England with snow on their boots. A journalist, observing the queer outlandish uniform of the Scouts and their wild-looking mounts, asked one of my friend’s comrades where they had come from. ‘From Ross-shire’, he said in broad Scots.

This was one of the few occasions when one of our officers bothered to speak to us. These cavalrymen were members of an exclusive military set and had their own ideas of discipline which, it must be admitted, worked extremely well. No doubt all their thoughts were on rejoining their units and getting back into action as quickly as possible, and probably if their subsequent careers could be traced it would be found that many achieved high command. Meanwhile they kept out of sight and left everything to a small band of N.C.O.s, dugouts like themselves, who treated us as they would have treated well-trained regular soldiers, many of whom did indeed leaven our ranks, bringing with them stories of the Boer War and of Omdurman.

Makeshift as everything was of necessity in an army swollen suddenly by the influx of thousands of untrained civilians, the system or lack of it worked amazingly well. There was little military crime; all duties were undertaken cheerfully and nobody complained. Yet for the first month we were half starved, and it was well into the New Year before we were equipped with khaki uniforms and stout army boots. Did the elegant dandies in the Officers’ Mess ever discuss the quality of this huge mob of new recruits put into their charge? They certainly took no apparent pains to study the problem.

Just one attempt was made to brighten our winter in Longmoor. An enterprising subaltern with the distinguished name of Lieutenant The Maclaine of Lochbuie brought down a number of well-known act...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword to the First Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Introduction to this Edition

- E. W. Parker

- Chapter 1 I Join the 15th Hussars

- Chapter 2 Field Operations

- Chapter 3 Transferred to the Durham Light Infantry

- Chapter 4 The Durham Draft Lands in France

- Chapter 5 The Journey up the Line

- Chapter 6 The Threshold

- Chapter 7 The First Working Party

- Chapter 8 Our Part in the Battle of Loos (25 September 1915)

- Chapter 9 With the Transport and the Bombers

- Chapter 10 Goodbye to Ypres

- Chapter 11 Tunnelling and Patrolling

- Chapter 12 The Anvil: Our Introduction to the Somme

- Chapter 13 The First Tank Battle in World History

- Chapter 14 Back to Arras

- Chapter 15 The Twenty-Ninth Division

- Chapter 16 The 2nd Battalion Royal Fusiliers Pull Caesar’s Nose: A Trench Raid

- Chapter 17 The First Passchendaele Battles

- Chapter 18 I Join the 13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers

- Glossary