- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

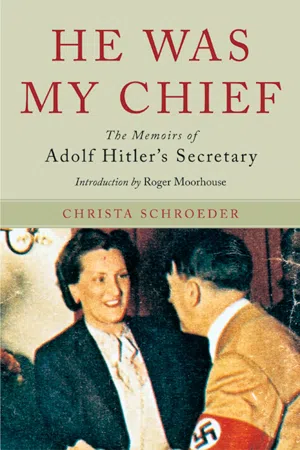

"A rare and fascinating insight into Hitler's inner circle." —Roger Moorhouse, author of

Killing Hitler

As secretary to the Führer throughout the time of the Third Reich, Christa Schroeder was perfectly placed to observe the actions and behavior of Hitler, along with the most important figures surrounding him. Schroeder's memoir delivers fascinating insights: she notes his bourgeois manners, his vehement abstemiousness, and his mood swings. Indeed, she was ostracized by Hitler for a number of months after she made the mistake of publicly contradicting him once too often.

In addition to her portrayal of Hitler, there are illuminating anecdotes about Hitler's closest colleagues. She recalls, for instance, that the relationship between Martin Bormann and his brother Albert, who was on Hitler's personal staff, was so bad that the two would only communicate with one another via their respective adjutants, even if they were in the same room. There is also light shed on the peculiar personal life and insanity of Reichsminister Walther Darré. Schroeder claims to have known nothing of the horrors of the Nazi regime. There is nothing of the sense of perspective or the mea culpa that one finds in the memoirs of Hitler's other secretary, Traudl Junge, who concluded "we should have known." Rather, the tone that pervades Schroeder's memoir is one of bitterness. This is, without any doubt, one of the most important primary sources from the prewar and wartime period.

As secretary to the Führer throughout the time of the Third Reich, Christa Schroeder was perfectly placed to observe the actions and behavior of Hitler, along with the most important figures surrounding him. Schroeder's memoir delivers fascinating insights: she notes his bourgeois manners, his vehement abstemiousness, and his mood swings. Indeed, she was ostracized by Hitler for a number of months after she made the mistake of publicly contradicting him once too often.

In addition to her portrayal of Hitler, there are illuminating anecdotes about Hitler's closest colleagues. She recalls, for instance, that the relationship between Martin Bormann and his brother Albert, who was on Hitler's personal staff, was so bad that the two would only communicate with one another via their respective adjutants, even if they were in the same room. There is also light shed on the peculiar personal life and insanity of Reichsminister Walther Darré. Schroeder claims to have known nothing of the horrors of the Nazi regime. There is nothing of the sense of perspective or the mea culpa that one finds in the memoirs of Hitler's other secretary, Traudl Junge, who concluded "we should have known." Rather, the tone that pervades Schroeder's memoir is one of bitterness. This is, without any doubt, one of the most important primary sources from the prewar and wartime period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access He Was My Chief by Christa Schroeder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

How I Became Hitler’s Secretary

AS A YOUNG GIRL I wanted to see Bavaria. I was told it was very different there from central Germany where I had grown up and spent all 22 years of my life. So, in the spring of 1930, I arrived in Munich and started to look for work. I had not studied the economic situation in Munich beforehand and I was therefore surprised to find how few job opportunities there were and that Munich had the worst national rates of pay. I turned down some work offers hoping to find something better, but soon things began to get difficult, for my few savings were quickly melting away. As I had resigned of my own accord from the Nagold attorney whom I had used as a springboard to Bavaria, I was unable to claim unemployment benefit.

When replying to an extremely tiny advertisement written in shorthand cipher in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten, I had no premonition that it was to open the doors to the greatest adventure, and determine the future course of my life, whose effects even today I am still unable to shake off. I was invited by an unknown organisation, the ‘Supreme SA leadership (OSAF)’ to present myself in the Schellingstrasse. In this almost unpopulated street with its few businesses the Reich leadership of the NSDAP, the Nazi Party, was located at No. 50 in the fourth floor of a building at the rear. In the past, the man who would later become Adolf Hitler’s official photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, had made his scurrilous films in these rooms. The former photographic studio with its giant oblique window was now occupied by the Supreme SA-Führer, Franz Pfeffer von Salomon and his chief of staff, Dr Otto Wagener.

Later I learned that I had been the last of eighty-seven applicants to keep the appointment. That the choice fell on me, a person being neither a member of the NSDAP nor interested in politics nor aware of who Adolf Hitler might be, must have resulted purely from my being a twenty-two year old with proven shorthand-typing experience who could furnish good references. I also had a number of diplomas proving that I had often won first prize in stenographic competitions.

Below the roof at No. 50 was a very military-looking concern, an eternal coming and going by tall, slim men in whom one perceived the former officer. There were few Bavarians amongst them, in contrast to the majority of men on the lower floors where other service centres of the NSDAP were located. These were predominantly strong Bavarian types. The OSAF men appeared to be a military elite. I guessed right: most had been Baltic Freikorps fighters.11 The smartest and most elegant of them was the Supreme SA-Führer himself, retired Hauptmann Franz Pfeffer von Salomon. After the First World War he had been a Freikorps fighter in the Baltic region, in Lithuania, Upper Silesia and the Ruhr. In 1924 he was NSDAP Gauleiter (head of a provincial district) in Westphalia, and afterwards the Ruhr. His brother Fritz, who had lost a leg and was prematurely grey, functioned as his IIa (Chief of Personnel).

In 1926 Hitler had given Franz Pfeffer von Salomon the task of centralising the SA men of all NSDAP districts. Originally, every Gauleiter ‘had his own SA ’ and his own way of doing things. Many were ‘little Hitlers’, which certainly did not serve the interests of unity in the Movement. As Hitler took upon himself the decision in all matters of ‘degrees of usefulness’, he considered it opportune to suppress the Gauleiters by centralising the SA. This was a clever chess move, for he envisaged the SA as the sword by which he proposed to force through the political will of the Party. Since this struggle did not go his own way, Hitler delegated this unpleasant job to Hauptmann Salomon. This ‘keeping myself out of it’ was a crafty move to which Hitler often resorted later. The Gauleiters were incensed by the reduction in their power, went all out for Salomon and constantly reported their worst suspicions about him to Hitler. Hitler had of course expected this, which was the main reason for his having delegated the job, and no doubt he gave an inward smile of satisfaction at his own foresight.

In August 1930 Hitler was obliged to give in to the pressure of the trouble-makers and sacrificed Pfeffer von Salomon, something which to all appearances he regretted having to do, although he did not much like the man. After making it clear that Salomon had outlived his usefulness, the latter resigned in August 1930, and Hitler took the opportunity to appoint himself Supreme SA-Führer in his place. Franz Pfeffer von Salomon was a critical sort of man. I often had cause to confirm this. One day for example I saw a copy of the Party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter lying on his table. It showed a photograph of Hitler. Salomon had doodled Hitler’s filthy, unkempt uniform jacket into a slim, tailored shape. The debonair Salomon seemed to find Hitler’s figure and manner of dressing, as probably much else, apparently not to his taste.

The OSAF chief of staff was retired Hauptmann Dr Otto Wagener, a former general staff officer and Freikorps street fighter, like Salomon from comfortable origins and full of vigour for putting Germany back on her feet. He had given up a directorship in industry and, relying on his comrade-in-arms Salomon, had followed Hitler’s call for collaborators. Dr Wagener lectured at Würzburg University. That he was a man of wide education with far-reaching contacts to politicians, industrialists and the nobility was obvious from the very comprehensive correspondence which I had to transcribe for him. Whilst he held the post of OSAF chief of staff, Dr Wagener drafted the ‘Economic-Political Letters’ whose length and multiplicity of subjects caused me much toil. My work for Dr Wagener was interrupted for a few weeks towards the end of 1930 when on Hitler’s orders he took over the leadership of the SA in September to fill the gap before the arrival of Hauptmann Ernst Röhm, recalled from Bolivia.

Ernst Röhm was the son of a senior railway inspector in Munich. He was commissioned in 1908 and in the First World War fought at Flaival on the Western Front. He was seriously wounded three times and lost the upper part of his nose to a shell splinter. He met Hitler in 1919 as a Reichswehr Hauptmann in Munich. As a liaison officer to the Reichswehr, Röhm was an important member of the Nazi Movement and was on familiar terms with Hitler. He was discharged from the Reichswehr for his involvement in the 1923 putsch, but a year later was active in the Deutsch-Völkische Freiheitspartei as a Reichstag Deputy and organised the National Socialist armed group Frontbann, although he gave up leadership of it once Hitler was released from Landsberg prison. At the end of 1928 he was reinstated in the rank of Oberstleutnant in the Reichswehr and as a general staff officer was sent to La Paz as a military instructor. In 1930 Hitler recalled him to lead the SA.

I then spent a couple of weeks with the Reich leadership of the Hitler Youth which at the time was housed in a private apartment. After the lively workload at OSAF I found this to be almost a punishment. When Dr Otto Wagener was appointed leader of the NSDAP Economics Office (WPA) on 1 January 1931, he asked for me as his secretary. The WPA offices with their various departments for Trade, Industry and Farming were located in the Braunes Haus at Brienner-Strasse 54, the former Barlow Palace opposite the Catholic seminary.12 Dr Wagener used to dictate long reports about discussions he had had without mentioning the name of the other party. He also made long trips away from the office, and on his return would dictate long memoranda which when complete would then disappear into his desk. I would often get annoyed about this unnecessary production of paperwork, or so it then seemed, and all too much cloak-and-dagger. It was not until 1978 when I read the book by H.A. Turner jr, Aufzeichnungen eines Vertrauten Dr h.c. Wagener 1929 – 193213 that I saw immediately that Wagener’s mysterious partner on his trips and discussions had been Adolf Hitler. His other conversation partners were Franz Pfeffer von Salomon and Gregor Strasser.

In my opinion these three saw in Hitler a singular visionary genius. They also recognised the danger of such genius which, strengthened by the suggestive power of his oratory, drew almost everybody under his spell. These three well-above-average men were probably agreed in taking the opportunity of the frequent and long conversations to test Hitler’s infallibility by queries and objections, which he would have not found pleasant. As his intuition could not be faulted with logic because it has a visionary origin and lacked any basis of logic, he considered them to be fault-finders and pedants and eventually he cast them aside.

OSAF Franz Pfeffer von Salomon was relieved of the post of OSAF and left out in the cold.14 At the end of 1932 secret negotiations between Gregor Strasser15 and Schleicher regarding his being offered the vice-chancellorship led to the total break with Hitler. In 1934 he was killed ‘by mistake’ during the Röhm putsch. Dr Otto Wagener moved to Berlin in 1932 and was relieved of all offices in the summer of 1933. Apparently his closest colleagues favoured him for finance minister. I never heard of him again.16 It is no wonder that hardly anybody knows the name after he withdrew and was apparently no longer required after 1933. No doubt Dr Wagener, Pfeffer von Salomon and Strasser were personalities with too much independence for Hitler’s liking. In any case, after Hitler took power I never heard them spoken of again.

A person then active in the OSAF who did achieve a meteoric rise was Martin Bormann, still of interest today to authors and historians. The worst character traits were attributed to him, and all decisions he imposed were blamed ‘entirely on him’ postwar, not only by journalists and historians but above all by the surviving NSDAP bosses, Gauleiters, Ministers and also people of Hitler’s entourage, who should have known better.

Martin Bormann was simply one of the most devoted and loyal of Hitler’s vassals who would often force through ruthlessly and sometimes brutally the orders and directives given him by Hitler. Seen in this way, Bormann followed the same kind of path as did Franz Pfeffer von Salomon, running battles with Gauleiters, ministers, Party bosses and the rest being the rule. In the spring of 1930 at OSAF, Bormann was as yet unburdened by the far-reaching and unpleasant tasks which Hitler gave him later. Bormann could never be called an attractive man. He had married Gerda Buch, the beautiful daughter of Party judge, retired Major Walter Buch, who as the Reich USCHLA judge in the NSDAP was highly respected and enjoyed Hitler’s confidence.17 Buch had been an active officer and subsequently an instructor at an NCO training school. In the First World War he was regimental adjutant and later commander of a machine-gun sharpshooter unit. In 1918 he took over an officer-candidate battalion at Döberitz. After the war he left the army in the rank of major and joined the NSDAP. In 1925 he was appointed USCHLA chairman, a position which required a lot of understanding for human inadequacies, much tact, energy and authority. He was predestined for the office, for his father had been president of the Senate at the Oberland tribunals in Baden. With his long face and tall, slim figure he always looked very elegant. He had been present at the marriage of his daughter to Martin Bormann, which was naturally very beneficial for Bormann’s prospects.

At OSAF, Martin Bormann headed the SA personal injury insurance plan designed by Dr Wagener, later known as the NSDAP Hilfskasse.18 All SA men were covered by it. At their gatherings there tended to be a lot of brawling which tended to result in bodily injuries. The insurance was useful and necessary. It was created to serve the single primitive purpose which the genius of Martin Bormann could not cover. Only after beginning work on the staff of the Führer’s deputy did Bormann succeed later in proving his extraordinary qualities. His career took off in the course of the 1930s. From chief of staff to Rudolf Hess he became NSDAP Reichsleiter and then Hitler’s secretary. He expected from his staff that same enormous industriousness which distinguished himself, and this did not help to make him loved. ‘Hurry, hurry’ was his celebrated phrase. Hitler, always full of praise for Martin Bormann, once said:

Where others need all day, Bormann does it for me in two hours, and he never forgets anything! . . . Bormann’s reports are so precisely formulated that I only need to say Yes or No . With him I get through a pile of files in ten minutes for which other men would need hours. If I tell him, remind me of this or that in six months, I can rest assured that he will do so. He is the exact opposite of his brother19 who forgets every task I give him.

Bormann came to Hitler not only well prepared with his files but was also so in tune with Hitler’s way of thinking that he could spare him long-winded explanations. Anyone who knew how Hitler did things will realise that this was decisive for him!

Many of the rumours still current about Bormann have in my opinion no basis in fact. He was neither hungry for power nor the ‘grey eminence’ in Hitler’s entourage. To my mind he was one of the few National Socialists with clean hands,20 if one may put it that way, for he was incorruptible and came down hard on all corruption he discovered. For his oppressive attitude in this regard he increasingly antagonised corrupt Party members and many others.

I am of the opinion today that nobody in Hitler’s entourage save Bormann would have had the presence to run this difficult office. For sheer lack of time Hitler could not attend to all day-today affairs, and perhaps whenever possible he avoided doing so to prevent himself becoming unloved! Accordingly all the unpleasant business was left to Martin Bormann, and he was also the scapegoat. Ministers, Gauleiters and others believed that Bormann acted from his own lust for power. I remember for example that at FHQ Wolfsschanze Hitler would often say: ‘Bormann, do me a favour and keep the Gauleiters away from me.’ Bormann did this and protected Hitler. The Gauleiters were as a rule old street fighters who had known Hitler longer than Bormann and felt senior to him. If a Gauleiter then happened to cross Hitler’s path while strolling, Hitler would play the innocent and gasp: ‘What? You are here?’ When the Gauleiter then held forth on Bormann’s shortcomings, Hitler would put on his surprised face. ‘I know that Bormann is brutal,’ Hitler said once, ‘but whatever he takes on is given hands and feet, and I can rely on him absolutely and unconditionally to carry out my orders immediately and irrespective of whatever obstructions may be in the way.’ For Hitler, Martin Bormann was a better and more acceptable colleague than Rudolf Hess had been, and of whom Hitler once said: ‘I only hope that he never becomes my successor, for I do not know whom I would pity more, Hess or the Party.’

Rudolf Hess was born in Alexandria, Egypt, the son of a wholesaler. His father came from Franconia and his mother was of Swiss descent. He was brought up in Egypt until aged fourteen, when he attended a special school at Godesberg on the Rhine, took the one-year examination and then a course in business practice which took him to the French-speaking region of Switzerland and then Hamburg. At the outbreak of the First World War he volunteered for military service and in 1918 was an airman with Jagdstaffel 35 on the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant. After the 1919 revolution he joined the Thule Society* in Munich and took part in the overthrow of the revolutionary councils in Munich, receiving a leg wound. Next he entered commerce and studied economics and history. One evening in 1920 he happened upon an NSDAP meeting and joined the Party immediately as an SA-man. In November 1923 Hess led the SA Student’s Group and was at Hitler’s side for the putsch attempt of 9 November 1923, being involved in the detention of the ministers at the Bürgerbräukeller. Following the failure of the putsch he spent an adventurous six months in the Bavarian mountains. Two days before the abolition of the Bavarian peoples’ court he surrendered to the police, was tried and sentenced immediately, and taken to Landsberg prison where he remained with Hitler until New Year’s Eve 1924. Later he became an assistant to the professor for geopolitics, General Haushofer, at the German Academy at Munich University. From 1925 he was Hitler’s secretary. Martin Bormann was certainly not dismayed by Rudolf Hess’s flight to Britain in 1941. I remember that on the evening of 10 May 1941, after Hitler and Eva Braun had gone upstairs, he invited a few guests sympathetic to him to his country house for a celebration. That evening everybody reported on how relieved he seemed!

The NSDAP economics department at Munich went on, but suffered changes of leader after the departure of Dr Wagener. For a short while Walter Funk, later the Reich economics minister, held the seat, and at the end of my spell in Munich it passed to Bernhard Köhler, known for his thesis Arbeit und Brot (Work and Bread). Köhler remains in my mind for his advice to me: ‘The person who defends herself, accuses herself!’ and dissuaded me from instigating an USCHLA hearing. My idea was to throw light on a slander circulating about me which was making my life in Munich hell.

The whole affair began with a telephonist hearing a surname incorrectly. The male telephonist at the Braunes Haus had misunderstood the name of a friend who had called me. Instead of Vierthaler, a pure Bavarian name, he misheard Fürtheimer, a Jewish name. Shortly before, in October 1932, I had gone on a coach excursion through the Dolomites to Venice with an older female colleague. The excursion had been arranged by a Herr Kroiss and his wife from Rosenheim. He drove the coach himself and had apparently taken a liking to me. As soon as we made a stop anywhere, Herr Kroiss and his wife would invite me to their table, ignoring my travelling companion. Herr Kroiss, who knew the route very well, was asked twice by three gentlemen in a large Mercedes where the best place was to spend the night. As fate would have it, these three gentlemen booked into the same Venice hotel as ourselves and even invited themselves to sit at our table. One of them invited me to take a trip with him in a gondola that afternoon, which I was pleased to accept, never suspecting what was in store for me as a result of my companion’s envy and feelings of being abandoned, and the telephonist’s later error at NSDAP HQ.

Back in Munich a friend, the niece of the NSDAP Reich treasury minister Franz Xaver Schwarz, surprised me with the question: ‘Christa, are you really having a relationship with a Jew?’ When I asked who had said so, she replied: ‘An SS-Führer!’ I asked her to have him present himself so that I could clear up the matter, and a couple of days later he turned up – I have forgotten his name – and asked me: ‘Do you perhaps wish to deny that you are having a relationship with the Jew Fürtheimer, and were together with him in Italy?’ My assurances and explanations availed me nothing, not even when my friend Vierthaler provided an affidavit swearing to his pure Aryan origins. A statement by Herr Kroiss that he organised his tours in such a manner that nobody could absent themselves overnight was similarly unsuccessful in putting an end to the accusations.

Bernhard Köhler, then my boss in the economics department, with whom I lodged the various affidavits told me: ‘Whoever defends herself, accuses herself!’ I did not understand the sense of this, but realised that he opposed an USCHLA hearing. Despite this proof of my manager’s confidence in me, the suspicions of the Party members smouldered and I suffe...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Editor’s Introduction

- Chapter 1 - How I Became Hitler’s Secretary

- Chapter 2 - The Röhm Putsch 1934

- Chapter 3 - Hitler’s Dictation and the Staircase Room

- Chapter 4 - Travelling With Hitler

- Chapter 5 - Hitler’s Birthday

- Chapter 6 - The Polish Campaign

- Chapter 7 - The French Campaign

- Chapter 8 - The Russian Campaign 1941 – 1944

- Chapter 9 - The Women Around Hitler

- Chapter 10 - Ada Klein

- Chapter 11 - Gretl Slezak

- Chapter 12 - Eva Braun

- Chapter 13 - Obersalzberg

- Chapter 14 - The Berghof

- Chapter 15 - The Order to Leave Berlin: My Leave-taking of Hitler

- Chapter 16 - The End at the Berghof

- Appendix

- Index