- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

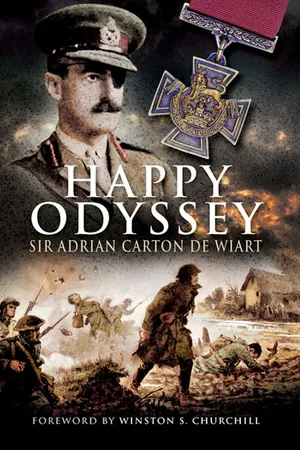

Happy Odyssey

About this book

The legendary British Army officer recounts his experiences in the Boer War and both World Wars in this memoir with a foreword by Winston Churchill.

Lieutenant General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart had one of the most extraordinary military careers in the history of the British Army. His gallantry in combat won him a Victoria Cross and a Distinguished Service Order, as well as an eyepatch and an empty sleeve. His autobiography is one of the most remarkable of military memoirs.

Carton de Wiart abandoned his law studies at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1899 to serve as a trooper in the South African War. During World War I he served both in British Somaliland and on the Western Front, where he lost his left eye to a bullet at the Battle of Somme. He went on to serve as a liaison officer with Polish forces, narrowly escaping the German blitz at the outbreak of World War II. He was part of the British Military Mission to Yugoslavia, taken prisoner by the Italian Army, and made numerous attempts at escape. He spent the remainder of the war as Churchill's representative in China.

The novelist Evelyn Waugh famously used Carton de Wiart as the model for his character Brigadier Ben Ritchie Hook in the Sword of Honour trilogy. In this thrilling autobiography, the legendary officer tells his own remarkable story.

Lieutenant General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart had one of the most extraordinary military careers in the history of the British Army. His gallantry in combat won him a Victoria Cross and a Distinguished Service Order, as well as an eyepatch and an empty sleeve. His autobiography is one of the most remarkable of military memoirs.

Carton de Wiart abandoned his law studies at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1899 to serve as a trooper in the South African War. During World War I he served both in British Somaliland and on the Western Front, where he lost his left eye to a bullet at the Battle of Somme. He went on to serve as a liaison officer with Polish forces, narrowly escaping the German blitz at the outbreak of World War II. He was part of the British Military Mission to Yugoslavia, taken prisoner by the Italian Army, and made numerous attempts at escape. He spent the remainder of the war as Churchill's representative in China.

The novelist Evelyn Waugh famously used Carton de Wiart as the model for his character Brigadier Ben Ritchie Hook in the Sword of Honour trilogy. In this thrilling autobiography, the legendary officer tells his own remarkable story.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

PREFACE

I BELGIUM, ENGLAND, OXFORD

II SOME BOER WAR SKIRMISHES

III HEYDAY

IV FIGHTING THE MAD MULLAH

V A CAVALRYMAN LOSES HIS SPURS

VI PASSCHENDAELE AND PARK LANE

VII HEAD OF THE BRITISH MILITARY MISSION TO POLAND

VIII FIVE SIMULTANEOUS WARS

IX POLISH POLITICS

X I AM GIVEN THE EARTH

XI SPORTING PARADISE

XII THE STORM BREAKS

XIII THE UNHAPPY NORWEGIAN CAMPAIGN

XIV ITALIAN PRISONER

XV PRISON LIFE AT VINCIGLIATI

XVI PLANS FOR ESCAPE

XVII WINGS OF A DOVE

XVIII MR. CHURCHILL SENDS ME TO CHINA

XIX CHINESE CHARIVARI

XX THE END OF IT ALL

XXI AND SO TO BED

INDEX

FOREWORD

I AM glad that my old and valued friend, Lieutenant-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, has written this book. I have known him for many years, and in the late war I felt the highest confidence in his judgment and services both in Norway and as my military representative with General Chiang Kai-shek. General Carton de Wiart has been decorated on several occasions for his valour in the field and services to his country and, in 1916, he gained the Victoria Cross. Although repeatedly wounded and suffering from grievous injuries, his whole life has been vigorous, varied and useful. He is a model of chivalry and honour and I am sure his story will command the interest of all men and women whose hearts are uplifted by the deeds and thoughts of a high-minded and patriotic British officer.

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

THE poem ‘The Toy Band: A Song of the Great Retreat’ is reproduced by permission of the Executors of the late Sir Henry Newbolt.

PREFACE

FOR some years my friends have been suggesting that I should write the story of my life. My answer has always been, ‘God forbid!’ They assumed that I must have had an adventurous life. I think it has been made up of misadventures. That I should have survived them is to me by far the most interesting thing about it. However, a bad accident as I was leaving China, necessitating many months in bed, and the feeling that I might never walk again made me think back on the years and try to jot down what I remembered of them. As I have never kept a diary there may be chronological errors for which I apologize in advance. These are simply the reminiscences of a lucky life; they have no pretensions to being either military or political history. I was much amused a little time ago to read in Punch that it was evident in view of the number of War Memoirs that were being published that generals were prepared to sell their lives as dearly in peace time as they had been in war. Apart from that inducement, I think it was also due to those lines of Lindsay Gordon which have always appealed to me:

One of these poets, which is it?

Somewhere or another sings,

That the crown of a sorrow’s sorrow

Is remembering happier things.

What the crown of a sorrow’s sorrow

May be, I know not; but this I know,

It lightens the years that are now

Sometimes to think of the years ago.

CHAPTER I

BELGIUM, ENGLAND, OXFORD

ACHILDHOOD of shifting scene and a mixed nationality may be responsible for my useful knack of growing roots wherever I happen to find myself. I was born in Brussels, a Belgian, the son of a successful legal man, and with an Irish grandmother to produce a small quantity of British blood in my veins. My wet nurse, with her vast starched strings, must have obscured my vision of anything else, for I can remember nothing of my infant days. My first real recollection is of Alexandria, where my parents took me when I was three, and I can still see the fierce fires shooting up into the sky to signal the warning of the dread menace, cholera. Then we came to England, and I have hazy memories of a dozing Surrey countryside where I was transformed into an English child and learned to speak French with a good British accent, and finally induced my parents to exchange my pleated skirt and large sailor hat for something a little more manly.

When I was six I lost my mother, and my father decided to uproot himself from Europe, transfer to Cairo and practise international law. My father’s sister and her family came to look after us, and saw to it that my French accent improved.

Suddenly my whole horizon changed, for in 1888 my father met and married an Englishwoman who was travelling abroad as companion to a Turkish princess. To my youthful eyes she appeared very pretty, but she was full of rigorous ideas accentuated by a strong will and a violent temper. My father’s house was cleared of all his extraneous relations, and I was given the English child’s prerogative, a little precious freedom, and encouraged in what was to be my first and lasting love, sport.

Originally I had been given a donkey to ride, usually hung round by attendants, but now I became the possessor of a pony, a polo pony, perfect in my eyes except for the living and terrible shame of a rat tail. The local photographer must have been a man of rare understanding, for when he came to take a picture of me astride my steed he sensed my shame, and thoughtfully embellished my pony with an impromptu tail.

One other gift marked the beginning of my sporting career. It was a small breech-loading gun, a Flobert, and with it I harassed the wretched Egyptian sparrow.

By this time I was tri-lingual for I could speak French, English and Arabic, and when an Italian governess appeared to plague me into learning Italian I thought it overdoing things and revolted. Our dislike of each other was mutual, her authority doubtful and her reign brief! I was then packed off to a day school run by French priests, memorable only because I was allowed to ride there every day on my charger.

In Egypt in those days a child’s chance of survival was very small, with a perpetual battle against disease. I was continually ill and eventually had to leave my day school to be put in the hands of an inefficient tutor.

Summer brought me still more freedom, for my father took a house at Ramleh, on the sea near Alexandria, where my stepmother proved herself an inspired swimming instructress by the simple expedient of throwing me in.

The rest of my childhood’s recollections can be summed up with a miniature gymnasium erected in the garden for physical jerks, an irrepressible mania for catching frogs, a love of pageantry and all things military. It was a life too lonely and formal to be truly happy, and I knew nothing of nurseries, plump kind nannies and buttered toast for tea.

All this time my father had been enjoying a most successful career as a lawyer and he had become one of the leading men in the country. Later he was called to the English Bar and became a naturalized British subject. His naturalization can have been only for business reasons, as although he had been educated in England at Stonyhurst he struck me always as a foreigner, and at heart I know that he remained a Belgian. My father was tall, neat, clever and hardworking, and the soul of generosity. He had two traits at variance with his legal calling, a guileless trust in man and no discrimination in people. He was utterly helpless and incapable of even shaving himself, let alone tying his shoe-laces, and I seem to have inherited from him one very trying habit of buying everything in dozens. We were on very good terms and I admired and respected him, but we were never intimate. Our interests lay too far apart for real understanding; he was a hard-working indoor man while I was idle and loved the out of doors.

No doubt because of my stepmother’s influence, my father decided to send me to school in England, and in 1891 I was dispatched to the Oratory School at Edgbaston near Birmingham. With mingled feelings of pride and trepidation I set out for the unknown.

In the early ’nineties conditions at the average public school were pretty grim. Food was bad and discipline strict, and there was a good deal of mild bullying – bad enough for a small English boy initiated at a ‘prep’ school, but very overwhelming for a Belgian boy who felt, and probably looked, a strange little object.

Foreigners are seldom enthusiastically received at English schools. They are regarded with grave suspicion until they have proved they can adapt themselves to traditional English ways and suffer the strange indignities which new boys are expected to endure with restraint, if not with relish. However, I was fairly tough and found that I really loved English games and had a natural aptitude for them. It was an easy road to popularity, and soon my foreign extraction was forgiven and in fact forgotten.

Cardinal Newman founded this school. In my time it consisted of only a hundred boys. It was too small, in my opinion – I met so few old schoolfellows in later life.

After a couple of years I began to enjoy myself. Fagging was behind me, work reduced to the irreducible minimum, and there was an endless procession of games. Eventually I became captain of the cricket and football elevens, won the racquets, tennis and billiards tournaments, and felt that the world was mine.

I am quite convinced that games play an extremely important part in a boy’s education, a fact ignored by most foreigners and a few Englishmen. They help him to develop his character in a number of ways, not the least being the ability to deal with and handle men in later years, surely one of the most valuable assets in life.

My holidays were distributed between my Belgian cousins and odds and ends of school friends in England.

In Belgium my relations are legion but my nearest and dearest were, and still are, my two cousins, both my contemporaries and now men of eminence. Count Henri Carton de Wiart was formerly Prime Minister, and Baron Edmond Carton de Wiart was at one time Political Secretary to King Leopold II, and is now Director of ‘La Société Générale de Belgique’. They owned various delightful houses; my favourite was Hastières in the Ardennes where we spent the summer on or in the river, scrambling over the hills or, like all boys in all countries, just fighting. One incident stands out in my mind with painful vividness. I was skating one Christmas on a lake on the outskirts of Brussels when I heard a shot fired in the woods surrounding the lake. I rushed in the direction of the shot and came upon a man, dead, with a revolver dropping from his hand, his coat open and the marks of the burn on his shirt where the bullet had gone through. It was the first time that I had come up against death, let alone suicide. I was haunted for many nights afterwards, and it did nothing to help to dispel my terror of the dark. It remains with me still.

By this time I had become indistinguishable from every other self-conscious British schoolboy and was invariably covered in confusion at the fervent embraces of my Continental relations. I should have got used to what was, after all, only a custom of the country, but it always made me feel a fool.

In 1897 it was decided to send me to Oxford, and in a rush of optimism I was put down for Balliol. I had overlooked the necessity for examinations and had rather an unpleasant shock when I tried and failed my first attempt at Smalls. But with the second attempt the authorities were kind and, after some delay because of a riding accident, I went up in January.

Once up at Balliol I thought the triumph of Smalls would carry me along for a term or two, and I prayed for a successful cricket season and visualized three or four pleasant years and a possible Blue.

We lived in great comfort, had indulgent fathers, ran up exorbitant bills and developed a critical appreciation for good wine, We were unable to develop a taste for the ladies as in those ascetic days they were barred from the universities.

We were the usual miscellaneous collection of brains and brawn, and though many of my contemporaries have become famous, illustrious in the Church, Politics and all the Arts, I then measured them by their prowess at sport or taste in Burgundy and remained unimpressed by their mental gymnastics.

My summer term was a great success as far as cricket was concerned, but scholastically it was a disaster. I was supposed to be reading Law, my father still nursing his illusions, but I failed my Law Preliminary, and realizing that my Oxford career would be brief, I felt a strong urge to join the Foreign Legion, that romantic refuge of the misfits. However, once again Balliol was lenient and I came up for the October term, when suddenly there were reverberations from South Africa and the whole problem was solved for me, most mercifully, by the outbreak of the South African War.

At that moment I knew, once and for all, that war was in my blood. I was determined to fight and I didn’t mind who or what. I didn’t know why the war had started, and I didn’t care on which side I was to fight. If the British didn’t fancy me I would offer myself to the Boers, and at least I did not endow myself with Napoleonic powers or imagine I would make the slightest difference to whichever side I fought for.

I know now that the ideal soldier is the man who fights for his country because it is fighting, and for no other reason. Causes, politics and ideologies are better left to the historians,

My personal problem was how to enlist. I knew my father would not allow it as he had set his heart on my becoming a lawyer, besi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Happy Odyssey by Adrian Carton de Wiart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.