eBook - ePub

From Warsaw to Rome

General Anders' Exiled Polish Army in the Second World War

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In May 1944, 40,000 Polish soldiers attacked and captured the hilltops of Monte Cassino, bringing to a close the largest, bloodiest battle fought by the western Allies in the Second World War. Days later the Allied armies marched into Rome seizing the first Axis capital.No-one in 1939 could have foreseen an entire Polish Corps engaged on the Italian Front. Most had been held prisoner in the USSR following Polands defeat and their release by Stalin was only achieved through the intense negotiations of British and Polish politicians generals, notably Sikorski and Anders,. The Polish Army was evacuated to Iran in 1942 and subsequently incorporated into the British Army as the Polish II Corps. Their ultimate postwar fate was shamefully ignored until too late.This book, which charts the extraordinary wartime story of the exiled Polish Army in the east, makes extensive use of undiscovered archive material. It reveals in depth the relations between the British and Polish General Staffs and the never ending hardships of the Polish soldiers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Warsaw to Rome by Martin Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The First Blitzkrieg

The summer of 1939 found the pivotal character of this saga, Lieutenant General Władysław Anders, in northeast Poland commanding the Nowogrodek Cavalry Brigade, whilst only a few miles away the German Army was massing across the border in East Prussia. Poland’s military commanders were exasperated by the weeks of political vacillation which had left the nation’s borders in a flimsy state of readiness – only in August had they been permitted to dig in and erect barbed-wire entanglements. The great flat plains of Poland lay open from the German border to the capital of Warsaw. The general mobilization order calling up all reservists was issued on 28 August, but was soon cancelled. This cautious approach was taken at the behest of the British, French and American ambassadors, who were all too aware that in every previous conflict involving Poland the defensive strategy adopted by Polish generals was that of pre-emptive attack. It was hoped that by not antagonizing the Germans unduly, war could be averted even at this late stage.

Their efforts were to no avail and on 1 September 1939 the Second World War broke out with the German invasion of Poland. General Carlton de Wiart headed the British Military Mission to Poland, his instructions from London making clear that his mission was to provide no more than moral support: ‘In view of the difficulties of rendering direct military support by British Armed Forces to the Poles, the question of inspiring confidence is of great importance.’1 In response to Nazi aggression Britain launched a leaflet-dropping campaign over Germany: the Poles were dismayed. Carton de Wiart advocated the Polish Army pulling back to firm defensive lines behind the River Vistula which were not actioned, while the Polish commander Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły steadfastly insisted on fighting for every inch of Polish soil; however the bulk of the Polish Navy was evacuated at the beginning of hostilities at the behest of the British Admiralty.

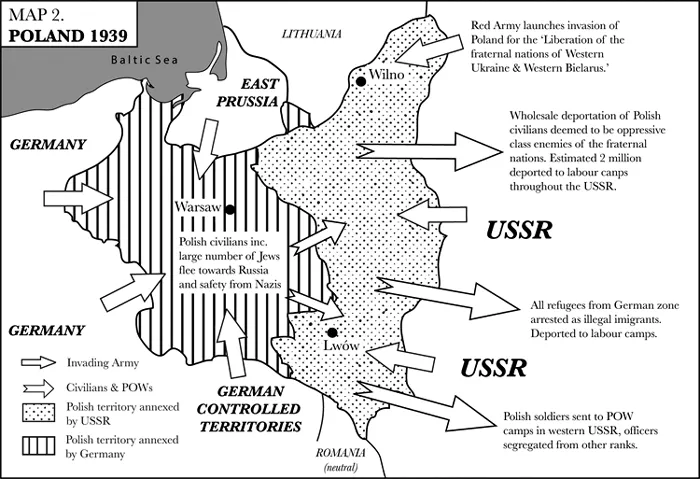

For Carton de Wiart and his staff the campaign was a revelation as the German all-arms Blitzkrieg rapidly overwhelmed the Polish Army and openly attacked civilians. Despite a valiant defence, the Polish troops were forced to fall back to defensive positions in the south-east of the country along the rugged Tatra Mountains bordering neutral Romania, holding out for the assistance of Britain and France, neither of whom the Poles realistically expected to do anything. Indeed the French Army announced it would take two years to prepare for an offensive. Such a response convinced the Polish General Staff that Britain and France were intending to allow Germany to seize Poland, whereafter the Entente would sue for some kind of peace settlement. The Polish defence was finally put paid to on 17 September due to the unforeseen invasion by the USSR and with the defence of the Tatra pocket no longer feasible the Polish Government ordered the evacuation of its army into allied Romania. Axis forces overcame the last elements of the army on 6 October. The country was subsequently divided between the two victor nations, although no formal surrender was ever issued by the Polish Government. Among the tens of thousands of captured soldiers was Lieutenant General Anders, who had been captured in the southern Polish village of Jesionka Stawiowa (now known as Yasenka Stets’ova) following a night of hand-to-hand fighting in which he sustained multiple wounds.

On 1 October 1939, Winston Churchill broadcast a radio message to the British people: ‘Poland has been again overrun by two of the great powers which held her in bondage for 150 years, but were unable to conquer the spirit of the Polish nation. The heroic defence of Warsaw shows that the soul of Poland is indestructible, and that she will rise again like a rock, which may for a spell be submerged by a tidal wave, but which remains a rock.’2

The eastern region of Poland was appropriated by the Soviets and garrisoned by large numbers of troops detailed to stop the Polish Army from evacuating and being reconstituted abroad, a point one of General Anders’ detaining officers made clear to him shortly after his capture: ‘We are now good friends with the Germans, together we will fight international capitalism. Poland was the tool of England, and she had to perish for that. There will never be a Poland again.’3 Along with the plunder extracted by the Soviets was the estate of General Carton de Wiart, who resided in Poland – the authorities removed his possessions and placed them in the Minsk city museum.

Commensurate with the Sovietization of eastern Poland, the captured Polish soldiers in this zone, along with countless civilians were deported by the NKVD (a forerunner of the KGB) deep into the Soviet Union to Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Siberia and other remote regions. All persons deemed to be actually or potentially hostile to the Soviet regime, a broad swathe of society encompassing all military personnel above the rank of private, all police officers, teachers, doctors, landowners and so on, were interned in camps and put to hard labour. This included the extraction of tree sap in arctic Siberia for the chemical industry, mining for asbestos and heavy metals, labouring on civil engineering projects and toiling on collective farms. The work took a heavy toll in lives for these deportees, the vast majority of whom had no experience of such hardships. The exact number of casualties has never been certain, but all those who survived the experience had clear recollections of the deaths of many of their compatriots.

Meanwhile, having conveyed much useful information about German warfare, General Carton de Wiart travelled from Paris to meet General Ironside, the Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial General Staff. He recounts that the opening remarks went as follows: ‘“Well! Your Poles haven’t done much!” I felt the remark was premature, and replied: “Let us see what others will do, Sir.”’4 Carton de Wiart was justifiably enraged by the dismissive attitude of the General Staff and when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain enquired with all sincerity as to the effectiveness of the Royal Air Force’s leaflet campaign the General’s reply was far from complimentary. The full impact of Germany’s Blitzkrieg had yet to register with the western powers, and many senior military and political figures could not adapt to the requirements of this completely new form of warfare. In the coming weeks both Ironside and Chamberlain were replaced, the latter of course by Churchill, a military innovator who far outpaced his contemporaries in his grasp of the impact of technology on warfare.

The Polish Government and General Staff had escaped to Romania along with the foreign military missions. A significant proportion of government figures including the prime minister and many soldiers were subsequently interned, as Romania was not at war with Germany and sought to appease German ambitions. Those who fled to Hungary faced a similar situation; both countries were neutral and had no desire to antagonize the Germans by playing host to the exiled Poles.

Of the Polish soldiers who evaded capture and escaped through Hungary and Romania, the majority headed for France and the centre of General Władysław Sikorski’s exile Polish Army based at Coetquidon in Brittany. Sikorski was appointed both prime minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army, at the urging of the French government. Sikorski was politically distanced from the leadership that had led his country to defeat, so his reputation was in far better shape than that of most senior officers in the eyes of the Polish soldiery and the international community. He also possessed a good reputation with the French, having spent much of the previous thirteen years in Paris and was most familiar with the leading French politicians and military figures. And the British Army held him in good stead, particularly General Ironside, who on his first inspection of the Polish Army observed that during Sikorski’s tenure as Minister of War, ‘The progress made by the Polish Army during the last years is remarkable.’5 General Sosnkowski was appointed Minister of Home Affairs and set to his business of organizing resistance warfare in occupied Poland, a role he had performed before against the Russians at the turn of the century. He was also appointed as the President’s successor.

The French were however distraught that war had broken out with Germany. They believed it to be totally avoidable and blamed the British for what they saw as an ill-conceived pact with Poland. Far from brimming with fighting spirit, they nonetheless were obliged to play host to the exiled Polish Army. Sikorski was adamant that only joint military participation in the war effort would guarantee the Allies’ commitment to Poland, and the creation of an army became a means of gaining international commitment to the Polish cause. Some 80,000 soldiers escaped capture and assembled in France before pressure from the Germans resulted in the route through Hungary and Romania being closed altogether, so that later evacuees had to make for the French Levant (Syria and Lebanon), where they joined the French colonial forces. From the winter of 1939 these men were billeted in Foreign Legion barracks in Homs, Syria and were organized as part of the French Army of the Levant, with their training and equipping well underway by January 1940. The formation was transferred to Polish command on 2 April 1940, becoming the Polish Carpathian Brigade, its staff and commander, Colonel Stanisław Kopański, arriving from Marseilles two weeks later.

The military campaign in France was a disaster for the Allies. An overwhelming German onslaught swept aside the armies of all opposing nations, leading to the capitulation of France and the need to evacuate all other Allied contingents to Britain. The Poles were acutely aware of this terrible situation and on 16 June prepared their first evacuation scheme, based on the principle that the struggle must be continued at the side of Britain. A consequence of the Franco-Polish alliance was that Polish units engaged at the front could not pull back and must fight to the end, an obligation Sikorski ordered his men to fulfil. However with the French signing their armistice with the Germans on 17 June, the obligation to send any more Polish troops into battle ceased. Sikorski met with Marshal Pétain that day and came to the conclusion that any help in the task of evacuation could only come from Britain. With this very much in mind, Churchill ordered an RAF bomber to fly to Bordeaux to collect the General and fly him direct to London for immediate talks with the British high command. Sikorski agreed to attend on the proviso that he be flown back to France straight after the talks to coordinate his army. Arriving on British soil Sikorski sent an appeal to Churchill on 18 June, which, while recalling the terms of the Anglo-Polish pact, contained a request for the provision of British warships and transports for the evacuation to Britain of the Polish units in France. ‘I desire to renew the assurance, that Poland stands resolutely at the side of H.M. Government in the camp fighting against Germany and I place my soldierly trust in you, Mr. Prime Minister, confident that at this hour of trial you will issue the necessary orders for the rescue of the Polish troops…which desire to continue the struggle at the side of the armies of His Majesty.’6

Sikorski was invited to meet Churchill that very morning at 10 Downing Street, where he told the prime minister that the Polish Army was determined not to surrender. His army was in fact threatened with total annihilation, the Germans having received orders to take no Polish prisoners; every Pole, officer or enlisted man, was to be executed. They had fought desperately, remembering the fate of their martyred countrymen at home. The close of the meeting was captured by the Sunday Express journalist George Slocombe (14 July 1940): ‘ “Tomorrow, I return to France…and I have to face my Army. What am I to tell them?” “Tell them,” replied Mr. Churchill, “that we are their comrades in life and death. We shall conquer together or we shall die together.”…The two Prime Ministers then shook hands.’ ‘That handshake,’ General Sikorski told Mr Slocombe afterwards, ‘meant more to [me] than any treaty of alliance, or any pledged word.’7 Immediate plans for evacuation were prepared and executed, some 23,000 soldiers and 8,000 airmen being transported to Britain over the following days.

Lieutenant General Sir Alan Brooke, commander of the United Kingdom Home Forces, called upon Sikorski on 31 July to arrange the employment of Polish troops, Brooke being responsible for coordinating Britain’s anti-invasion preparations. The discussions led to the signing of the Anglo-Polish Military Agreement on 5 August 1940, formalizing Sikorski’s earlier pledge. The British Government recognized the autonomy of the Army of the Sovereign Polish Republic under the Supreme Command of the Polish Commander-in-Chief, though in practice the British high command would direct operational strategy and control joint operations. Lieutenant General Sir Alan Brooke made this point plain in his diary with the phrase ‘[the] Polish Troops being now under my orders.’8 The Polish Army was to be formed under Polish operational command and military laws, unlike the much smaller Polish Air Force and Navy that became integral parts of the British Armed Forces – this was largely because the British establishment recognized that the Polish Army was now the only surviving Polish institution of any size and the sole remaining symbol of their sovereignty. Polish soldiers were nevertheless subject to British criminal and civil law, which was seen as necessary to curb the practice of duelling amongst the officers.

The collapse of France shattered all hopes that the war might be over quickly and Poland’s necessary dependence on military cooperation with Britain meant that the war had now to be seen from the British perspective, as a global conflict, along with the realization that Polish troops would have to fight on battlefields away from Europe. The only immediate military option open to Sikorski was to form an expeditionary force from the Poles in the French Levant, whose ranks had swelled to some 3,000. This growing force was however in a difficult situation, being based in Vichy French territory, and the French commander of the Levant Army, General Huntziger, ordered the arrest of Colonel Kopański when the latter refused to disarm and instead insisted on leaving Syria with full military equipment. Kopański’s firmness won through, he openly refused to yield to threats and the Brigade marched out of Syria and into Palestine with colours flying. Thanks to secret assistance from the French General de Larminat, the Poles were able to acquire arms and munitions, and thus equipped they joined the British Army in Palestine. The British commanding officer in Palestine, General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, noted that the evacuated soldiers contained a high proportion of officers, in fact larger numbers than could be absorbed. A special unit of ex-officers had therefore to be created, christened the Polish Officers’ Legion.

The first real test of this Anglo-Polish pact came with the Italian declaration of war on 10 June 1940, bringing the possibility of military conflict between the Allied troops in the Suez region and Italian troops from Ethiopia and Eritrea. In response, the British proposed using the Polish Independent Carpathian...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1 The First Blitzkrieg

- 2 A Polish Army in the USSR

- 3 Exodus to the Middle East

- 4 Along British Lines

- 5 A Year of Challenge

- 6 Ready to Fight

- 7 The Move to Italy

- 8 Mountain Warfare and the Defence of the Sangro River

- 9 The Monastic Fortress

- 10 Preparations for Battle

- 11 Assault on the Gustav Line

- 12 A Brief Respite

- 13 Victory at Monte Cassino

- 14 Breaking the Adolf Hitler Line

- 15 The Aftermath

- Notes

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Plate section