- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

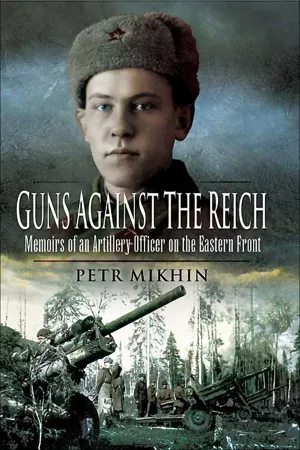

About this book

"[A] powerful autobiography from a Russian veteran of Stalingrad, Kursk and numerous other battles . . . as he fought his way from Moscow to Vienna." —

Military Illustrated

In three years of war on the Eastern Front—from the desperate defense of Moscow, through the epic struggles at Stalingrad and Kursk to the final offensives in central Europe—artillery-man Petr Mikhin experienced the full horror of battle.

In this vivid memoir he recalls distant but deadly duels with German guns, close-quarter hand-to-hand combat, and murderous mortar and tank attacks, and he remembers the pity of defeat and the grief that accompanied victories that cost thousands of lives. He was wounded and shell-shocked, he saw his comrades killed and was nearly captured, and he was threatened with the disgrace of a court martial. For years he lived with the constant strain of combat and the ever-present possibility of death. Mikhin recalls his experiences with a candor and an immediacy that brings the war on the Eastern Front—a war of immense scale and intensity—dramatically to life.

"Mikhin's memoirs give us a very valuable picture of life in the Red Army during four years of intense non-stop fighting against a determined and skilled enemy. This allows us to follow the evolution of the Red Army from the nearly defeated force of 1941 to the skilled military machine of 1945, and helps illuminate the price that the Soviet soldiers paid for victory." —History of War

"A fast-paced, interesting read that recounts stories of courage under fire and dedication to duty . . . I highly recommend this book." —Military Review

In three years of war on the Eastern Front—from the desperate defense of Moscow, through the epic struggles at Stalingrad and Kursk to the final offensives in central Europe—artillery-man Petr Mikhin experienced the full horror of battle.

In this vivid memoir he recalls distant but deadly duels with German guns, close-quarter hand-to-hand combat, and murderous mortar and tank attacks, and he remembers the pity of defeat and the grief that accompanied victories that cost thousands of lives. He was wounded and shell-shocked, he saw his comrades killed and was nearly captured, and he was threatened with the disgrace of a court martial. For years he lived with the constant strain of combat and the ever-present possibility of death. Mikhin recalls his experiences with a candor and an immediacy that brings the war on the Eastern Front—a war of immense scale and intensity—dramatically to life.

"Mikhin's memoirs give us a very valuable picture of life in the Red Army during four years of intense non-stop fighting against a determined and skilled enemy. This allows us to follow the evolution of the Red Army from the nearly defeated force of 1941 to the skilled military machine of 1945, and helps illuminate the price that the Soviet soldiers paid for victory." —History of War

"A fast-paced, interesting read that recounts stories of courage under fire and dedication to duty . . . I highly recommend this book." —Military Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Guns Against the Reich by Petr Mikhin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

THE RZHEV MEAT-GRINDER

Prologue

Training is hard…

The early morning of 22 June 1941 was exceptionally beautiful, quiet and sunny. It was peaceful, except for the airplanes. Their engines roared as they flew back and forth over the city. However, everyone thought that this was just an exercise. People had worried about the possibility of war in early May and June, but one week before, on 14 June, there had been a placating message from TASS, the official Soviet news agency. It stated that we should not be afraid of the concentration of German troops on our borders, as they were only resting there before their final push on England.

We, three students of the Herzen Pedagogical Institute, Aleks Kurchaev, Viktor Iaroshik and I were preparing for our third-year final exam. Our dormitory was located behind the institute, just a short walk away. Suddenly the loud voice of a narrator sounded from a loudspeaker: ‘Listen to Molotov’s speech at noon.’ We decided to linger, as we were interested to hear what the state’s second-in-charge would tell us.

Molotov announced the outbreak of the war in a tragic, mournful and entreating voice. His words stunned us. Our hopes, plans, lifestyles and everyday concerns – all were gone. Even our lives no longer belonged to us. Our worst fears had become a menacing reality. But we were all certain that we would swiftly defeat the enemy.

Without watching our steps, we rushed to the third floor of the institute, where about twenty students were standing in the long corridor. I shouted down the corridor: ‘Comrades! War with Germany has begun!’

Shocked by the message, students gathered around me and asked where I had heard the news. Before I could say anything more, someone in the crowd sharply tugged my sleeve. I turned around and saw the faculty’s Party secretary. ‘What sort of provocation is this?! You are making this up!’ he roared, firmly holding me by the sleeve. ‘Do you know what will happen to you for slander?! Follow me to the Party office now!’

Suddenly at the other end of the corridor, another voice rang out: ‘Guys! It’s war! War!’ The Party secretary ran off towards the new source of commotion, allowing us to step into the classroom where the exam on mathematical methodologies was being held. Our Professor Krogius, an elderly, tall and thin, very strict educator, showed no reaction at all to our announcement about the war. ‘Please pick up your exam questions,’ he said calmly, as if nothing had happened.

I thought: ‘Perhaps this Krogius is a German and he’s known about the war for a long time?’

All three of us passed the exam with distinction. We exited the building onto the grounds, which were boiling with activity: crowds of students, discussions, arguments, all sorts of hubbub. Finally, the institute’s Party secretary arrived at the scene and everyone fell silent. The secretary briefly repeated Molotov’s announcement, called for vigilance and ordered us to wait for further instructions. Students shouted: ‘Send us to the front!’

We, students of the Physics and Mathematics faculty, decided to go to the Kuibyshev District voenkomat [military commissariat]. Once there, however, an employee of the voenkomat emerged to announce that all the students were to gather in the yard the next morning at 8 o’clock, and to bring jackets, spoons, mugs and personal kits. They’d be sending us to the front. We all rejoiced.

The next morning we marched in formation to the Finland Station, where we boarded a train that carried us to Vyborg. There we were accommodated in tents that had already been pitched in a pine forest. A field kitchen supplied us with food. We were shown a prepared trench in the sandy soil and given an order: in the course of the day, each fellow was to cut down twenty pine trees, remove all the branches and cut them into shorter logs. Soldiers would use the logs to reinforce the walls of the trenches, so that they would not collapse. The girls were ordered to dig an anti-tank ditch.

The goal of twenty trees turned out to be very hard to meet, and no one managed to reach it before the onset of darkness. For the next several days, we worked twelve-hour days. We were extremely exhausted, but gradually got used to the work and began to reach the daily norm with daylight remaining. It would have been OK if not for the mosquitoes and flies; we had no place to hide from them.

But where was the promised front?!

We began to demand from the colonel who was overseeing our work to be sent to the front. Two students who traveled to Leningrad to pick up soap told us when they returned that it had been impossible to walk the streets, as every person they encountered had been indignant over the fact that two healthy students were not in the army. We threatened the colonel with a strike, if he didn’t send us to the front.

Yet all the same, we had to labor there for almost a month, until our work was finished. A German airplane overhead dropped a bomb on us once. It was frightening, but no one was hurt.

On 23 July we returned to Leningrad and headed off to the local voenkomat the next day. There we were formed into four ranks, told to count off, and then were split into two groups and led off in opposite directions. My group marched across the city towards Finland Station, but before we reached it, our column stopped in front of an iron gate. After the gate opened, we were directed inside onto a paved yard and told to take a seat along a fence to rest. No one knew where we were, and there was no one to ask. Only the barbers, who eventually appeared to shave our heads, explained that this was the 3rd LAU – Leningrad Artillery Specialist School. We learned later that our comrades from the second group had been sent to an infantry specialist school.

First, we were taken to a bania [bath-house] and issued with cadet uniforms. After we washed and changed into our cadet uniforms, our appearance had changed so dramatically that we could recognize a friend only by looking at him directly in the face. After returning to the paved grounds of the specialist school, we were divided into platoons, shown our barracks and then marched in formation to a mess hall. We liked the meal: it was abundant, tasty and filling. We were all happy in spite of ourselves; thank God, at least we didn’t have to worry about our daily bread.

They also issued good uniforms to us. Although they were cotton, not wool uniforms, they were new and durable. Those days not every student could boast of decent clothing. For example, I only had one pair of trousers, which I ironed from time to time, and a felt jacket instead of a proper suit. My friend Viktor Iaroshik from Byelorussia lacked not only a suit, but even proper trousers. He went around in the black cotton training trousers that we were issued with for gym. They looked good while doing gymnastics, because they were tight and emphasized the straightness of the legs when working on the parallel bars or the pommel horse. But when Vitia went to the club for dances in these athletic slacks, they didn’t give him a good appearance. Viktor only managed to attract the girls because of his athletic figure and handsome, tawny face.

We also appreciated the canvas-topped boots we received. They were heavy compared to our gym shoes, but they offered good support, and on marches, they seemed to carry us forward all by themselves. But their best feature was that they were waterproof. They were my first waterproof boots; before, my boots had always leaked, especially in the slush and puddles of spring.

The next day was already a full day of training, from reveille at 0500 hours to taps at 2300 hours: morning calisthenics and a jog along the Neva River before breakfast, and then ten hours of classes with only a short break for lunch. In the evening we had two hours of self-study. There was no time for rest. We had to complete the normal three-year course of training in four months. During field exercises, the gun crew of eight had to push around, unlimber and deploy the 12-ton cannon like it was a toy and each shell weighed 43 kilograms. We used a huge mallet to hammer the 100-kilogram steel stakes into the ground to stake down the gun trails. We never got enough sleep. Our entire bodies ached. When at four o’clock in the morning we were marched to the bania, we learned to sleep on the move. It turned out to be nothing: you woke up at halts, when bumping into the man in front of you.

On one of the Sundays I got a permission to run to my institute to pick up letters. My brother wrote me from the Moscow area, informing me that he had volunteered for an opolchenie (home guard) division. Spirits were high in the opolchenie; everyone was very patriotic and eager to get to the front, although they had no training and no weapons. I sensed that my brother was feeling very militant and optimistic, because the political workers were convincing the 17year-old volunteers that the Germans would soon exhaust their resources and then it would not be hard to defeat them. My brother also wrote that the home guard volunteers were worried that they might arrive too late at the front, and the war would end without them.

Soon these opolchenie divisions met a bitter fate. They were used to plug holes in the front and were vainly sacrificed.

Our political workers were also talking to us about the situation at the front. Mainly, they were telling us which towns had been surrendered to the Germans. The fascists’ rapid advance unsettled us, angered us and amazed us. We had been raised on triumphant Soviet movies and songs, and we couldn’t understand how it could happen that the Germans were already approaching Moscow.

Before the war, we had constantly heard lectures on international affairs at the institute. We knew that the British and the French were dragging out the negotiations and in fact didn’t want a treaty with us against Hitler, which forced Stalin into the [Molotov-von Ribbentrop] treaty with the Germans. Of course, the nation didn’t believe in friendship with Hitler, and people disapproved of the policy of flirting with Nazis, but they kept this mainly to themselves. For example, my uncle Egor Illarionovich Sakharov, a simple peasant though also a collective farm brigade leader who later was killed at the front, told me the following: ‘Stalin is afraid of Hitler, flirts with him and pays him off with grain and coal, just like my son Pet’ka buys off the older boys with apples so that they won’t beat him up.’

The Soviet people had lived in the nervous expectation of war. But no one thought that it would start so suddenly.

A month flashed by in diligent training. At the end of August, an order arrived for the evacuation of our artillery school to Kostroma. We transported all the academy’s belongings to the Finland Station and loaded them onto trains. On 3 September we set off for Kostroma along the Northern Railway in cargo cars. As soon as we had passed Mga, the Germans captured it and the siege of Leningrad began.

Just like in peacetime, locals along the route were selling berries in paper cups: blackberries, cloudberries, blueberries. They were very exotic for us and we treated ourselves to the berries.

Along the route, just in case, we were issued with old Polish carbines. Although our commanders reminded us about the well-known army saying that even an unloaded rifle can fire once a year, one cadet accidentally killed his neighbor while cleaning his carbine. It was the first death that we saw.

We arrived in Kostroma and found accommodations in the barracks of a reserve regiment that had departed for the front. The schedule of training remained as tough as it had been in Leningrad.

My brother sent me a last letter from a place en route to the battlefield: ‘We’re on our way to smash the Nazis!’ They were without weapons, as I found out later. I received no further letters from him after that.

We diligently studied the artillery sciences all through September, October and November. On 5 December we graduated as lieutenants, and received two little bars of rank for our collar tabs. In all, 480 freshly-commissioned lieutenants were sent to the front, while the top twenty lieutenants in physical strength and political reliability, I among them, remained behind and were sent to Orenburg for a training course as aerial observers. After the training course we would be correcting artillery fire onto enemy positions from airplanes and hot-air balloons.

In the first days of January 1942, we arrived at the 2nd Chkalov Military Aviation School. On the very first night we were robbed. Instead of our fine, long woolen artillery overcoats, we found threadbare little coats with air force insignia hanging on our hangers the next morning. We later had to spend the entire winter in these air force coats.

Training at the Chkalov School was also very intense. In addition to navigation and the rules for directing artillery fire from an airplane, they began to torment us with Morse code training for six hours a day, in the morning, after lunch and in the evening. We had taps of ‘ti-ta ti-ta-ta-ta’ ringing in our heads and our finger bones hurt from working the key.

Not even a month had passed, when Marshal Voroshilov suddenly arrived at our military aviation school. We were assembled in a hall, about 200 lieutenants from different artillery specialist schools. The Marshal, wearing a simple soldier’s overcoat, announced: ‘We’re bringing you back to earth and returning you to the field artillery.’ They didn’t want to waste any more officers, as all the previously trained air observers had been killed, because our air force didn’t yet have any reliable and maneuverable reconnaissance planes, like the German ‘Frame’ [the FW 189].

So we were directed to the 25th Reserve Artillery Regiment in Gorkii. Here we got to know the full measure of cold and hunger.

We lived in bunkers, each of which had two rows of bunk beds stretching along both walls, sufficient to accommodate 1,000 men. The bunkers were about 100 meters long, with wide gates at each end. A stove made from an iron barrel stood at each entrance. The stoves were red-hot, but this didn’t rescue us from the cold – water would freeze inside the dugout. As we crowded around the stove, our overcoats would start to smoke, but our backsides would be freezing. Only hay covered the bunk beds, which were made from roughly-hewn boards. To try to keep warm, five of us would lie tightly next to each other on our right sides, covered by our five overcoats. Then on command, we would all turn over onto our left sides. This is how we tossed and turned the entire night, almost not sleeping.

Among the lieutenants of our group, there was a young actor from Moscow. He immediately made contact with the Latvian waitresses, who were working in the six officer canteens. The five of us managed to have six breakfasts and five lunches, but we were still hungry – we could get six hundred grams of bread per day in only one of the canteens, while the others served only a watery hot broth.

Most of the officers and men in the training camps longed for the front with only one aim in mind: to get a full stomach. Some of the soldiers could not endure this life, and while standing guard at night with their rifles, shot themselves.

At the end of February, our group was summoned to Moscow, to the personnel department of the Moscow Military District, where we were assigned to military units. Three lieutenants, including me, were sent to Kolomna, into the then-forming 52nd Rifle Division, and there I was given the duty of adjutant to the commander of the 1028th Artillery Regiment.

We arrived in Kolomna at night and were quartered in a hotel. For the first time that winter we laid down in clean beds in a warm room. No one wanted to leave the cozy hotel the next morning.

When we arrived at the regiment, which was stationed in a village just outside of the town, all three of us were placed with a peasant family. It turned out that the adjutant’s post was not vacant, so I was appointed deputy commander of a howitzer battery. Our battery commander, Senior Lieutenant Cherniavsky was a frontovik [an officer or soldier with front-line experience] and had arrived at Kolomna from a hospital. Thirty-five years old and the former chief engineer of the Murom plywood factory, Cherniavsky was smart, practical and knew his business. Under his leadership, we set about creating a combat battery out of some Gorkii collective farm workers.

The soldiers were getting very little food, we officers a bit more, but we were still all hungry. There was no place to buy extra food, as the locals were also all starving. When the first grass appeared in the fields, my soldiers almost scared me to death. I was marching my platoon down a field path for an exercise, when all of a sudden without my command they all dispersed and began crawling along the ground, like they were under air attack. I was scared – I couldn’t understand what was going on. It turned out that the soldiers had spotted some edible grass by the roadside and had all rushed to pick it and have an afternoon snack.

All of us, both officers and men, young and old alike, regarded Cherniavsky like a strict but caring father. He was short, slim, wide in the shoulders and a bit stooped. His swarthy, angular face was always covered with black stubble, even though he shaved daily. The piercing gaze of his dark eyes and his tightly compressed jaws always gave his expression a resolute appearance. We all looked the same in our khaki cotton tunics and trousers; only the three dark green pips of rank and the binoculars hanging around his neck made Cherniavsky stand out among us.

Taciturn, businesslike and demanding – when one looked at Cherniavsky, one also wanted to grit one’s teeth and keep working and working. We believed in him and loved him – for his experience, his fatherly care, and for his clear heart. He never lectured us, never swore and never gave us a tongue-lashing. Even when we made serious mistakes, he never rebuked us, but only had to shake his head disapprovingly and a guilty soldier was ready to die from shame. Cherniavsky valued highly resourcefulness and diligence, and everyone tried to display these traits.

At the time our training was more classroom than practical; we had no cannons or almost any other equipment. It was good that I had the thought to borrow four wagons and teams from a nearby collective farm, which our Sergeant Major Kho...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Part One: The Rzhev Meat-Grinder

- Part Two: From Stalingrad to the Western Border

- Part Three: Here it is, Eastern Europe!

- Index