- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

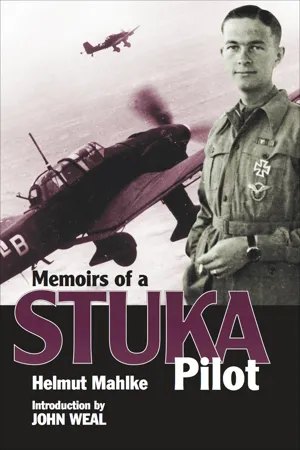

Memoirs of a Stuka Pilot

About this book

"Well-written and holds the reader's attention . . . an engaging book and a rare personal view of flying one of the most iconic aircraft of WWII." —

Firetrench

After recounting his early days as a naval cadet, including a voyage to the Far East aboard the cruiser Köln and as the navigator/observer of the floatplane carried by the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer during the Spanish Civil War, Helmut Mahlke describes his flying training as a Stuka pilot.

The author's naval dive-bomber Gruppe was incorporated into the Luftwaffe upon the outbreak of war. What follows is a fascinating Stuka pilot's-eye view of some of the most famous and historic battles and campaigns of the early war years: the Blitzkrieg in France, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, the bombing of Malta, North Africa, Tobruk, and Crete, and, finally, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Mahlke also takes the reader behind the scenes into the day-to-day life of his unit and brings the members of his Gruppe to vivid life, describing their off-duty antics and mourning their losses in action. The story ends when he himself is shot down in flames by a Soviet fighter and is severely burned. He was to spend the remainder of the war in various staff appointments.

"An engaging, engrossing and exceptionally informative book. A worthy addition to any military enthusiast's library and is unhesitatingly and heartily recommended." —Aviation History

After recounting his early days as a naval cadet, including a voyage to the Far East aboard the cruiser Köln and as the navigator/observer of the floatplane carried by the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer during the Spanish Civil War, Helmut Mahlke describes his flying training as a Stuka pilot.

The author's naval dive-bomber Gruppe was incorporated into the Luftwaffe upon the outbreak of war. What follows is a fascinating Stuka pilot's-eye view of some of the most famous and historic battles and campaigns of the early war years: the Blitzkrieg in France, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, the bombing of Malta, North Africa, Tobruk, and Crete, and, finally, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Mahlke also takes the reader behind the scenes into the day-to-day life of his unit and brings the members of his Gruppe to vivid life, describing their off-duty antics and mourning their losses in action. The story ends when he himself is shot down in flames by a Soviet fighter and is severely burned. He was to spend the remainder of the war in various staff appointments.

"An engaging, engrossing and exceptionally informative book. A worthy addition to any military enthusiast's library and is unhesitatingly and heartily recommended." —Aviation History

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Memoirs of a Stuka Pilot by Helmut Mahlke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías militares. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Childhood

Born in Berlin-Lankwitz in August 1913, my very first recollection of soldiers dates back to the days of the First World War. My father, a local government senior planning officer in Berlin, was a Hauptmann der Reserve (captain in the reserve) and commander of a railway engineer company that saw service in both France and Russia.

During one brief spell of home duty he had ridden ‘tall in the saddle’ at the head of his company as it marched through the streets of our neighbourhood. We cheered and waved from the pavement. Although I was only a tiny little fellow, my father gestured for me to be lifted up to him. He sat me in front of him on the horse’s broad back and let me ride along for part of the way.

It naturally made a huge impression on me. These were real … daten – my infant tongue couldn’t manage all three syllables of the word ‘Soldaten’, the German for ‘soldiers’ – and it was my very own father who was leading them! Young as I was, I can still clearly recall how proud I felt of him, and for days afterwards I could talk of nothing but the … daten.

As I was the youngest of her three children, my loving mother lavished special care and affection on me. Times were hard and food was short. Mother was able to rent a small plot of land close to our flat, and this she cultivated so successfully that we had the basic necessities to survive. Being the daughter of a country vicar and having grown up in a rural parish, she knew how to grow things. I was allowed to help her, but I suspect that my early attempts at weeding did a lot more harm than good. It soon taught me, however, that – even when times were bad – it was always possible to keep one’s head above water with a little initiative and the use of one’s own hands.

The First World War ended in revolution. Father returned home to a Berlin that was full of unrest. At night he would go out on patrol as a member of a volunteer security force charged with maintaining law and order on the streets. Mother was greatly concerned for his safety. But quiet finally descended on the city again and life got back to some semblance of normality – if the mere absence of immediate danger to life or limb can be described as normal!

The situation remained desperate, however. The whole nation was suffering under the yoke of the Treaty of Versailles. As a child I only ever heard the treaty referred to as the ‘disgraceful Diktat’. It was apparently the cause of all our woes and, together with the lies about our war guilt, had wounded the country’s pride deeply. It was the subject of endless discussion among the grown-ups.

And then came inflation. The value of money fell so catastrophically from one day to the next that on one occasion father came home from work with four packets of typing paper. They had swallowed his entire week’s civil service salary. Mother was furious! How was she supposed to feed her family on four thousand sheets of paper? Father tried to pacify her by pointing out that the same amount of money wouldn’t even be enough to buy a single loaf of bread the following day. Besides, he was lucky to have got the paper just before the shop shut. He needed it for the reports he had to write in his part-time job as a municipal dry-rot inspector. And somehow or other mother managed to cope, no doubt by dipping into the small stock of produce harvested from the tiny allotment that she still tended.

These were very hard times for all Germans – and the ‘disgraceful Diktat’ was seen as the root cause of everything. But in response there was a surge of national pride in the hearts of the nation’s menfolk. With a growing sense of confidence and self-assurance, our fathers began to regard themselves as responsible citizens of their Fatherland once more.

I give just one small example to illustrate my point: as a young boy, whenever my parents entertained guests I would be invited into the ‘salon’, where the ladies were drinking mocha, and allowed to serve them with milk and sugar. Afterwards I would pass around the cigars and offer lights to the gentlemen gathered in the smoking room. There they would stand – professors, engineers, bankers, teachers and clergymen – their chests swelling with pride and with iron watch-chains dangling from their waistcoats. These chains were inscribed with the words: ‘I gave gold for iron.’ Their owners were fond of boasting about the amount of tax that they had paid … and the larger the amount, the prouder they were! They saw their contributions to the nation’s coffers as both an expression and a measure of their civic worth.

Who could imagine anything of the like happening among a similar group today? If the subject of tax came up at all, the conversation would no doubt revolve around the different sorts of dodges that could be employed to ‘save’ on one’s tax bill. But back then the tax system, and the voting system, were both very different. Even so, we could still learn a thing or two from our fathers, one being that it is not always right simply to make demands and expect the state to provide. Instead, it should be the responsibility of every citizen to support the state to the best of his own particular ability.

As a ten-year old I was permitted to type out father’s reports and thus earn myself a modest amount of pocket money. I am still amazed to this day at the unending patience my father displayed as he slowly and carefully dictated his shorthand notes to me. At first he would often have to spell out unfamiliar words letter by letter. But I was full of enthusiasm and felt that I was helping the family and being very grown up, especially when I received my first ‘wages’ – the very first few Pfennigs that I had ever earned in my life, and which I naturally looked after with great care!

Father continued to let me earn my pocket money in this way right up until my Abitur, my final school exams. At first I got ten Pfennigs for every mistake-free page of typing that I produced. Later this was increased to twenty Pfennigs, and by the time I reached the sixth form it had risen to the princely sum of fifty Pfennigs per sheet. This allowed me to finance my hobbies. My first purchase was an ancient linen-covered canoe that was only held together and kept watertight by the numerous coats of paint applied by its many previous owners. But I loved messing about in that canoe and on hot summer days I was the scourge of Berlin’s Wannsee. Later I was even able to treat myself to a ten-hour course of riding lessons.

The world of politics meant little to us children. That was something for the grown-ups. Nor were we subjected to any overt political pressure at school. All our free time was spent playing games, hiking and in sporting activities of every kind. We realised, of course, that our parents were very conservative and rigid adherents of the German National People’s Party. They were firmly convinced that our country was still being unfairly shackled by the terms of the Versailles Treaty.

My parents felt this particularly keenly, as they had spent their first years of married life in the German colony of Tsingtao on the coast of China. Here at the turn of the century my father, in his role as government building supervisor, had overseen the construction of various official buildings. My parents had many interesting tales to tell of the big wide world. But Germany’s overseas colonies had also been lost as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. Admittedly, conditions at home had gradually improved over the course of the intervening years, but the blame for all the difficulties that remained was – as always – still placed fairly and squarely at the doors of the ‘disgraceful Diktat’. The older generation had to struggle on burdened by the knowledge that, for the foreseeable future, no matter how hard they worked or how many sacrifices they made, it would not alter the fact that the Fatherland lay helpless and humbled.

It was against this background that in 1931 – aged seventeen and just having passed my Abitur – I volunteered my services to the Reichsmarine as an officer-cadet. By so doing I genuinely believed that I would be making my own small contribution to the development of our nation. At the same time, of course, I also hoped that it would give me the opportunity to experience at first hand those far-off places and peoples that my parents had spoken of, and which I read about in the books by scientists and famous explorers that I devoured whenever I could get my hands on them.

But to my great disappointment I was turned down. The reason given was ‘6kg underweight’. True, as a child brought up in the big city during the lean wartime and post-war years, I was not very sturdily built; in fact, when it came to trials of strength in gymnastics or sports I was a total washout. But I could more than hold my own when stamina and endurance were called for, and so I didn’t abandon my aims straight away.

I therefore decided instead to study marine engineering and aeronautical design at the renowned Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg, my reasoning being that this could only be of benefit to me in ultimately achieving the profession of my dreams. In the meantime I continued to call in on the city’s naval recruiting officer at regular three-monthly intervals in order to find out whether, and in what other ways, I could improve my chances of a military career.

I must have made the poor man’s life a misery with all my inane questions: demanding to know, for example, if the Navy really did go shopping for its officer-cadets on the basis of bodyweight alone? It was meant light-heartedly. But, just to be on the safe side, I thought I should perhaps eat a bowl of oatmeal porridge every day in an effort to put on those missing pounds. (This was a decision not taken lightly, as back then porridge oats were not the tasty treat that they are today. They were full of coarse grains that stuck in one’s gullet and it required several hard swallows to get each mouthful down.)

I also described to the recruiting officer the steps I was taking to prepare myself as far as possible for my hoped-for naval career, including the studies at Charlotten burg and my enrolling for a sailing course with the Hanseatic Yacht Club Neustadt up on the Baltic coast. I added that I would also like to learn to fly, but that unfortunately my parents couldn’t afford the tuition fees. He must have made a note of this latter snippet, for during the second visit of my renewed round of applications for the following year’s intake, things finally started to happen.

After the usual medical examination I was asked to attend a two-day ‘psycho-technical aptitude test’, at the end of which I was required to come back again the following day. It was all terribly secretive. A jovial gentleman of advanced years welcomed me in a very friendly manner. Then he began to ask me a lot of questions. I couldn’t for the life of me see where all this was heading. I was worried that he wanted to trip me up somehow. For example, he showed me a silhouette and asked, ‘What’s that?’ – ‘It’s a silhouette,’ I replied – ‘Yes, but what does it show?’ – ‘A hare sitting up on its hind legs in a field.’ – ‘And can you picture the hare hopping away across the field?’ – ‘No.’ – ‘Why not?’ – ‘Because it’s not really a hare, just a silhouette.’

For a good hour I kept asking myself what was the point behind all this question and answer business. But at last came the question that explained everything: ‘Do you, in fact, know why you are here?’ – ‘Because I have volunteered to join the Navy.’ – ‘True, but I’m actually a doctor of aviation medicine and my job here today is to assess your suitability for pilot training.’ This was absolute music to my ears! In the highest of spirits I sailed through the rest of the examination – and this time with success.

A few weeks later the naval recruiting officer telephoned to arrange a visit to my parents. I took the precaution of preparing them beforehand: ‘If he should ask whether you consent to my being trained as a pilot, there’s only one possible answer: “Yes!”’ But mother was naturally concerned. She quoted the old proverb about not trusting oneself to the water, before adding, ‘… and as if that’s not bad enough, now you want to go up in the air as well?’ In the end, however, my parents gave me their blessing. I nonetheless received yet another deferment from the Navy, although in the same post I got my enrolment forms for the Deutsche Verkehrs flieger schule [German Commercial Pilot’s School] at Warnemünde.

On 1 April 1932 I was one of eighteen hopeful naval officer-candidates who presented themselves for final selection at Warnemünde, a small town on the Baltic coast north of Rostock. Twelve of us would be taught to fly here. The other six would depart to join the Navy’s normal sea officer’s training course. This was the last hurdle!

Proceedings began with yet another aircrew medical examination. The doctor’s female assistant led off with the usual: ‘If you would please strip, gentlemen.’ This brought a prompt rejoinder from our Roderich Küppers: ‘After you, miss!’ And that set the tone. The whole affair was very informal and relaxed (although the doctor’s assistant had sadly declined Roderich’s invitation). When it came to my turn the doctor asked, ‘How come you have such rosy lips? Do you use make-up?’ That’s some thing you probably know more about than I do, I thought, and so I answered in a similarly light-hearted vein, ‘Naturally – but only the very best 4711 Eau de Cologne, of course!’ His answering grin showed that he had a sense of humour and that we understood each other.

Later we were taken up for a test flight – a first for all of us – during which we were allowed to ‘stir the stick around a little bit’ to determine whether or not we possessed a natural ‘feel’ for flying. It’s a funny thing: either you ‘have it’ – in which case you can be taught to fly – or you don’t. And if you don’t, you’ll never master the art of flying however hard you try. Nobody knows where it comes from. The ‘Old Eagles’ of the First World War used to say that a natural flyer is born with it in the seat of his pants. And that’s as good a place as any until some scientist inves-tigates further and comes up with an alternative answer – or can perhaps suggest a different part of the anatomy!

At the end of the examination the doctor delivered his verdict on each of us. In my case, after appearing to ponder for a while, he announced: ‘Well, he may have the complexion of a young girl, but he goes at things like a terrier after a rat!’ – which was his somewhat unorthodox way of saying that I was in, one of the twelve ‘new boys’ who would be joining the Warnemünde German Commercial Pilot’s School. I felt as if I had just won the lottery! Firstly, I had been one of only ninety naval officer-candidates selected from over 2,000 applicants. And then, of those ninety, I was one of just twelve who had been chosen for flying training! What I had only dared to hope for in my wildest dreams was now about to become reality.

Chapter 2

Training to be a Naval Pilot

We spent the first four weeks attending a course at the Hanseatic Yacht Club at Neustadt in Holstein, where we were introduced to the basic rules of seamanship; in other words, everything that we needed to know in order to be able to manoeuvre small boats (and later also floatplanes) about on the water without danger to ourselves or to others.

Then we moved along the coast to Warnemünde to begin flying training proper. The aircraft we flew were Udet U 12a Flamingos, the same type of machine that the ex-First World War fighter ace, Ernst Udet himself, was currently using at air shows up and down the country to thrill the crowds with displays of his flying ability and aerobatic artistry.

The Flamingo was an open cockpit, two-seater biplane – primitive in the extreme by today’s standards – but ‘fully aerobatic’ nonetheless. The instructor sat in the front seat, the pupil behind him. Details of each flight had to be finalized before takeoff, for once the engine was running there was no means of com munication between the two occupants, as the machine had neither radio nor intercom.

To get the engine to start it had to be hand-cranked by a member of the ground crew. This was not an altogether safe occupation. Before the ignition was switched on the propeller needed to be swung a few times and then – with the ignition now on – the mechanic had to give one last almighty ‘heave’ while, at the same time, leaping smartly out of the way as the engine sprang into life. If he was not quick enough he ran the risk of being injured, or even killed by the whirling blades. Safety was therefore always of paramount importance during this procedure.

There weren’t many controls in the Flamingo, just the petrol cock to regulate the supply of fuel to the engine, the ignition lock and key, the throttle, the elevator trimming wheel (rudder trim could only be adjusted on the ground by means of the trim tabs) and, finally, the control column and rudder pedals. This meant there wasn’t a lot that could be forgotten or overlooked, and consequently rapid progress was made during our early training flights. These always began with the instructor doing everything first, while the pupil simply rested his hands and feet lightly on the controls to ‘get the feel of things’ before he then replicated the instructor’s movements.

Initially we concentrated on ‘circuits and bumps’. This was to teach us how to take off and land. After only a few lessons the instructors began to place both hands in plain sight on the cockpit sill, which meant that the pupil was expected to perform the take-off ‘on his own’. Landings were much harder, however, as the trainee had to learn how to judge and coordinate his height, course, angle of approach and landing speed correctly in order to touch down alongside the landing cross.

This was important at Warnemünde where, in those days, the landing ground was little more than a tiny patch of grass. If you came in too fast or too high you would invariably overshoot and have to go round again. Anyone forced to fly this extra circuit, known as the ‘lap of honour’, was sure to be the butt of some good-natured ragging from his comrades when he eventually got down.

And if a pilot came in too high and with too little speed the resulting heavy landing – a ‘boomps landing’ as it was then commonly called – would inevitably bend the mainwheel axle so badly that it had to be straightened out before the machine could take off again.

But this was not as serious as it sounds. A couple of mechanics would be called across from the workshops – if they weren’t already on their way, that is; they seemed to possess some sort of sixth sense as to when their services were going to be needed! Armed with a large iron crowbar apiece, they would advance on the machine with the weary measured tread of the true mechanic, shove a crowbar int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Plates

- Foreword

- Foreword to the English Edition

- Chapter 1: Childhood

- Chapter 2: Training to be a Naval Pilot

- Chapter 3: Naval Officer’s Basic Training

- Chapter 4: Foreign Training Cruise

- Chapter 5: Transferred to the Luftwaffe

- Chapter 6: Shipboard Aviator

- Chapter 7: Training to be a Stuka Pilot

- Chapter 8: Staffelkapitän in the Campaign against France

- Chapter 9: Operations over England as Gruppenkommandeur

- Chapter 10: Malta and the Mediterranean

- Chapter 11: Operations in North Africa

- Chapter 12: Trapani/Sicily

- Chapter 13: Operation ‘Merkur’ – Crete

- Chapter 14: The Russian Campaign

- Chapter 15: Ground-Support Operations

- Afterword

- Appendix 1: III./StG 1 Pilot Roster At the Close of the Campaign in France

- Appendix 2: Pilots of I.(St)/186(T) and III./StG 1 Killed or Missing in Action, 1939–40

- Appendix 3: Pilots of I.(St)/186(T) and III./StG 1 Posted Away 1939–40

- Appendix 4: Ground personnel Killed, Missing or Died on Active Service, 1939–45

- Appendix 5: Extracts from I.(St)/186(T), III./StG 1 and III./SG 1 Casualty Reports