eBook - ePub

Posters of The Great War

Published in Association with Historical le Grande Guerre, Peronne, France

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Posters of The Great War

Published in Association with Historical le Grande Guerre, Peronne, France

About this book

Until the arrival of radio and television, and despite the influence of newspapers, posters were the major medium for mass communication. During the Great War all the belligerent nations produced an extraordinary variety of them - and they did so on a massive scale. As the 200 wartime and immediate post-war posters selected for this book reveal, they were one of the most potent, and memorable, ways of conveying news, information and propaganda. In the most graphic and colourful fashion they promoted values such as patriotism and sacrifice. By using rallying symbols such as flags as well as historical and mythical models, they sought to maintain morale and draw people together by stirring up anger against the enemy. Today their remarkable variety of styles give us an instant insight into the themes and messages the military and civilian authorities wished to publicize.The sheer inventiveness of the poster artists is demonstrated as they focused on key aspects of the propaganda campaign in Britain, France, Germany, America and Russia. The diversity of their work is displayed here in chapters that cover recruitment, money raising, the soldier, the enemy, the family and the home front, films and the post-war world. A century ago, when these images were first viewed, they must have been even more striking in contrast to the poor-quality newspaper photographs and postcards that were available at the time. The Great War was to change that forever. It introduced a means of propaganda that was novel, persuasive and above all, powerful. It was the first media war, and the poster played a key role in it.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Recruiting

It is no coincidence that the largest number of posters in the ‘Recruitment’ category are British. Before 1914, both France and Germany had obligatory military service for men, so that in August 1914 the French army already numbered 1,300,000 men, including colonial troops. The German army was even bigger, comprising in 1914 almost 1,750,000 men, and there were a similar number in reserve, as all men between the ages of 17 and 45 were required to undergo compulsory service. These were significant figures compared to the size of the British Regular Army at the outbreak of the war, which was a little over 710,000 strong including reserves, and of these only 80,000 men were sufficiently equipped to go to war. The majority of the army was spread thinly across the world, policing Britain’s far-flung colonial interests. In part the reason for this was that the British had always been opposed to conscription, and even the idea of retaining a standing army was a contentious one.

Initially, 100,000 volunteers were asked for in a direct appeal by Lord Kitchener, fronted by the famous ‘Your Country Needs You’ poster, which was issued on 7 August 1914. The government believed that any more men would simply cause logistical problems, but in the event such was the rush to join the colours that by January 1915 over a million men had volunteered. The initial belief of the British high command that the war would be short and sharp soon vanished in the smoke of the battles of 1914. It soon became painfully clear that far more men would be needed than had ever been thought possible. In France the British Expeditionary Force had lost 90,000 men in the first three months of the fighting – more than its original size, although curiously the near-defeat of British forces in the early battles such as Mons helped fuel enlistment. Nevertheless, the government was becoming increasingly uneasy about the rate at which men were being killed and wounded, and the inability of the army to replace them. This, of course, was not unique to Britain: French and German losses in 1914 had also been huge, but those countries still held sufficient reserves for the numbers to be made up. Britain’s problem was that by late 1915 the rate of volunteering was slowing, for by then the numbers of men enlisting had dropped to around 70,000 per month. This was not enough to maintain the level of manpower needed, and both posters and other popular media such as music halls were used to recruit more young men. The tone of the posters being produced began to change from straightforward patriotic pleas to ‘Fight for King and Country’ to more subtle messages. Imagery became more frightening and graphic as propaganda became better organised. Rumoured German atrocities, the threat of invasion and even the capture of civilians and implied rape appeared on billboards around the country. There was little doubt that such methods were needed as the war progressed. Conscription had to be introduced in January 1916 for single men but even this was insufficient: the Somme battles alone, for example, required 3,000 replacement soldiers per day. In the United States the army was sufficiently large, at 98,000 men, to send troops to Europe as soon as hostilities were declared, so that there were 14,000 Americans in France by June 1917 with an additional 25,000 arriving every week. By the summer of 1918 a million American servicemen were in France. In part these numbers were attainable only through conscription, but this did not prevent the American government from embarking on a huge poster campaign to encourage voluntary enlistment, but generally such posters tended to be aimed less at enlistment and more at promoting the war effort. It is doubtful whether recruiting posters had any effect whatsoever in any country by late 1917, although they continued to be produced. Without the United States’ entry into the war, it is questionable how much longer Britain and France could have continued hostilities. Unlike weapons or money, the numbers of soldiers that could be created was finite.

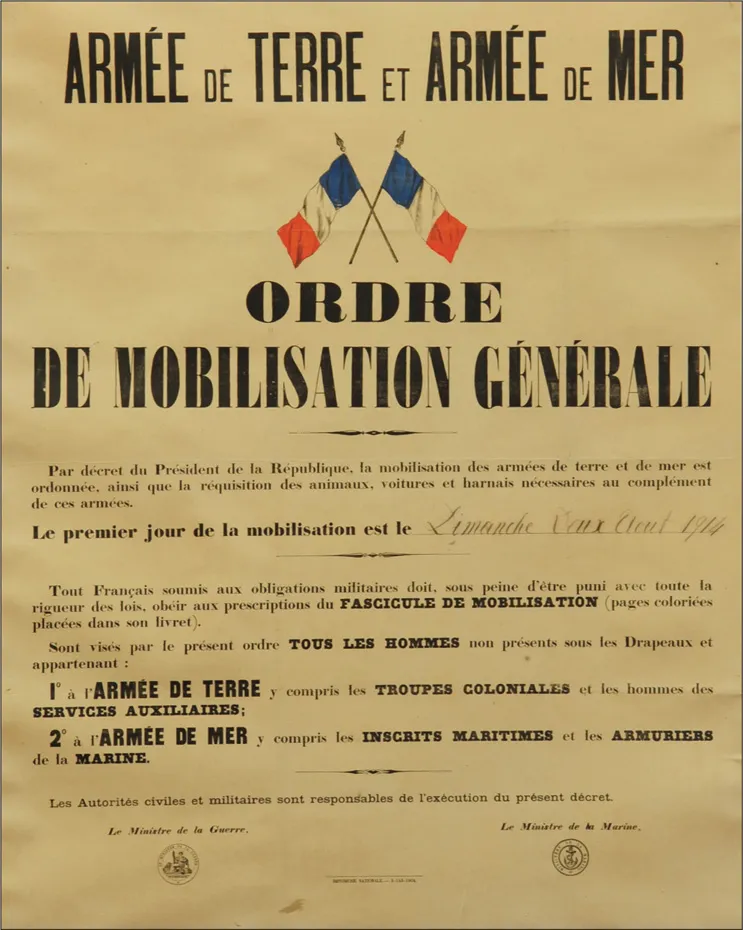

‘Order of general mobilisation.’ A simple administrative poster with two flags announced the French general mobilisation. Each mayor had received an envelope containing several copies. When the Prefect gave the order, the envelope would be opened and the exact date would be added. The image of French soldiers happily going off to war with flowers attached to their rifles is largely a myth. Despite small nationalist demonstrations in Paris, most of the population, still very rural, regretted not being able to harvest the crops. The overall feeling was one of quiet determination to defend country and family against what was perceived as German aggression.

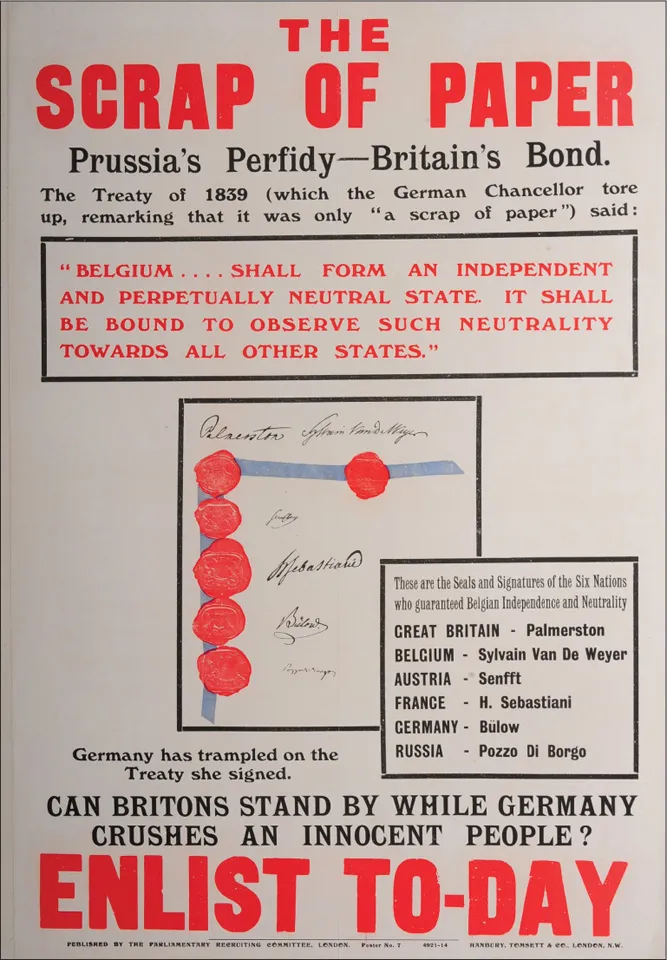

An early poster outlining the Treaty of Belgium and highlighting the apparent indifference of the German Chancellor to its content. The fact that the treaty was signed thirty years before the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and bore little relevance to the politics of 1914 was carefully ignored. The appeal was to the emotions rather than to historical accuracy.

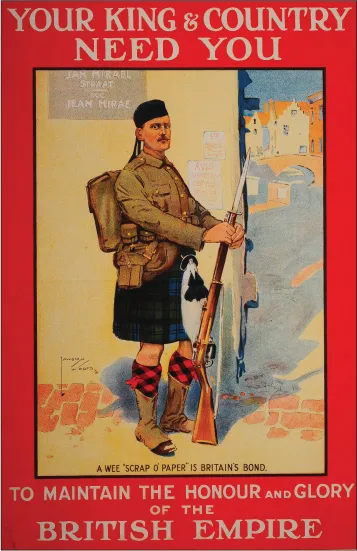

Another reference to the ‘Scrap of Paper’. The detail in this 1914 painting by war artist Clarence Lawson Woods (1878–1957) is worth a second look as the rather pensive-looking Highlander’s uniform and equipment have been very accurately reproduced, an unusual feature in posters of this type. The explanation is that Wood had served in the army as a Kite Balloon officer, and was decorated for gallantry. He worked for the Graphic, the Strand, Illustrated London News and Boy’s Own newspaper but after the war he became a recluse. However, his lifelong concern for the welfare of animals earned him a fellowship of the Royal Zoological Society in 1934.

Although the artist is unidentified, this is the first depiction of John Bull in a military poster, and dates to 1914/15. Created in 1712 by Dr John Arbuthnot, ‘John Bull’ represented a typical simple, good-hearted English yeoman, not particularly heroic but always adhering to the British sense of fair play. He proved to be the ideal representation of the ordinary Englishman and was to appear regularly in posters during the Great War, being represented in the United States by the figure of Uncle Sam.

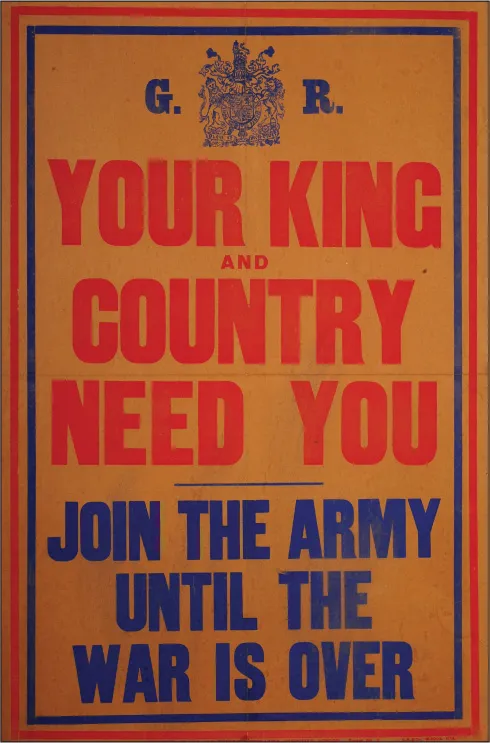

This is one of the simplest but most often reproduced recruitment posters of the war. The message is clear and unmistakable, and examples were reproduced in varied sizes: as huge bill-hoardings, large shop-window posters and newspaper pages. They were everywhere, and are still one of the most commonly found posters of the war, although in many respects the sentiments today would no longer be thought of as relevant.

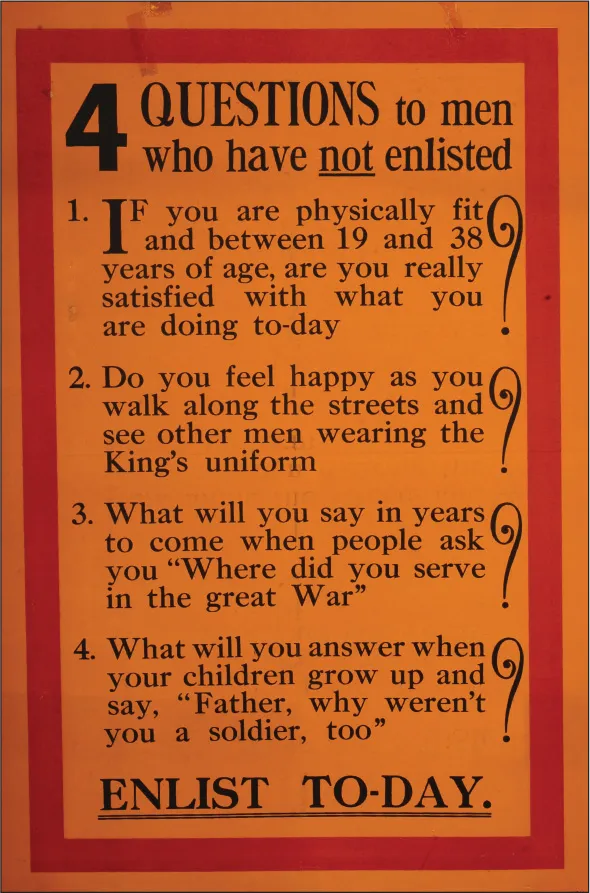

A more subtle poster, pricking the conscience of the ordinary man in the street, this embodies many elements of later posters, particularly the fourth item, which pre-dates the later, famous, ‘What Did You Do In The War?’ poster. It plays on the fact that men who did not join up would have to wrestle with their consciences in later life.

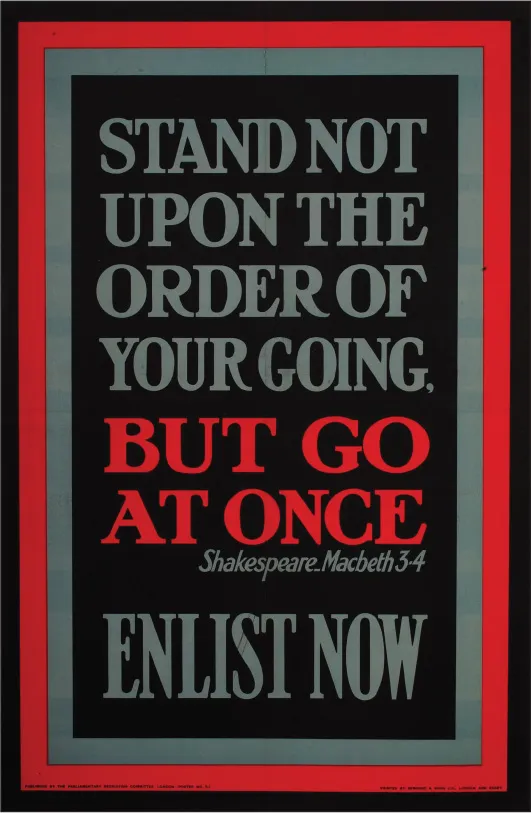

A rather unusual literary example, quoting Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth (Macbeth, Act 3, Scene IV). Although it is arguable that the message would be lost on many of the ordinary public today, in Edwa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Historial de la Grande Guerre

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Recruiting

- Chapter 2 Loans and Money

- Chapter 3 The Soldier

- Chapter 4 The Enemy

- Chapter 5 The Family and the Home Front

- Chapter 6 Films

- Chapter 7 After the War

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Posters of The Great War by Frédérick Hadley,Martin Pegler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Modern Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.