- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Return Via Rangoon

About this book

This is one young officer's war story about training and inspiration in the Burmese jungle behind enemy lines. Beaten up and water tortured, yet only giving his captors false information, Stibbe was moved around Burma until he was eventually imprisoned in Rangoon jail. Now stricken with Parkinson's disease, probably as a result of his prison diet, Stibbe with his eldest son, also a soldier, has revised his book and this edition published to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Wingate's second triumphant Chindit expedition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Contents

| Part I – PREPARATION | |

| 1. | Travelling |

| 2. | Training |

| 3. | And More Training |

| Part II – ACTION | |

| 4. | Jhansi to the Chindwin |

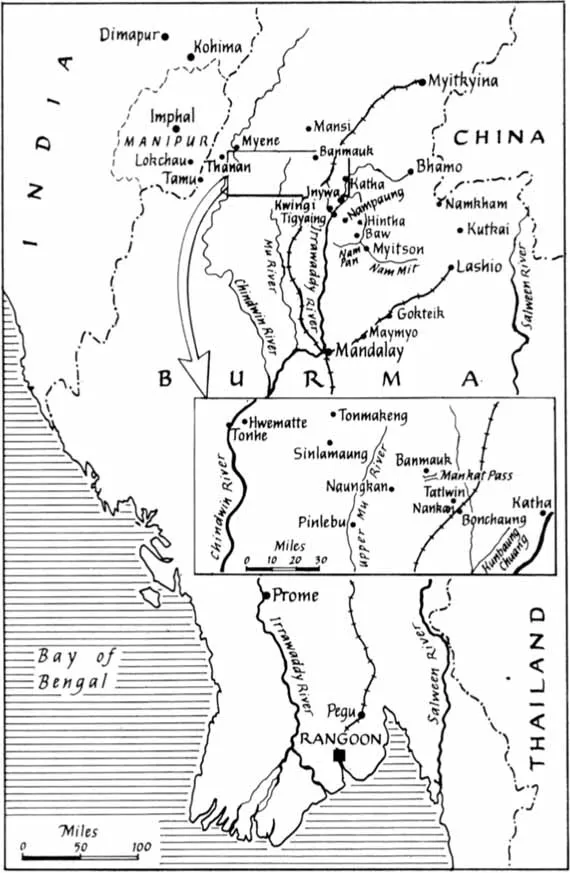

| 5. | The Chindwin to Tonmakeng |

| 6. | Tonmakeng to Bonchaung |

| 7. | Bonchaung to Tigyaing |

| 8. | Tigyaing to the Hehtin Chaung |

| 9. | The Hehtin Chaung to Hintha |

| Part III – CAPTIVITY | |

| 10. | Hintha to Bhamo |

| 11. | Bhamo to Maymyo |

| 12. | Maymyo to Rangoon |

| 13. | Six Block |

| 14. | Three Block |

| Part IV – DELIVERANCE | |

| 15. | The March |

| 16. | 29 April, 1945 |

| 17. | The Journey Home |

| Epilogue | |

| Appendix | |

PART I

Preparation

“Not all the modern, easy ways of life have been able to eradicate the hard core of native toughness in the British race … The modern British soldier, once trained, is capable of feats of endurance as great as any of the past.”The Good Soldier by Viscount Wavell

CHAPTER 1

Travelling

The damp blanket of sea mist that enveloped us, the strident calls of seagulls, fog horns, and ships’ sirens, all melancholy, formed a fitting background to my mood as I leant over the rails watching the water slide by the ship’s side. For a few moments the mist lifted to reveal a glimpse of Scottish coastline, steep grey cliffs below and brown bracken slopes above, with patches of vivid green pasture where some very bedraggled sheep grazed. Lucky sheep, I thought; at least you can stay in your own land with your own flock instead of being herded on to a boat with a crowd of strangers, and not only sent abroad, but sent to India, the last place on earth anyone in their senses would want to visit. The mist closed in again and the ship slid on, carrying me and my alternating sorrow and resentment out into the Atlantic.

It is more than forty-five years, since that day but it remains as clear as yesterday in my memory. At that period of my life I was utterly insular. My passion for the English countryside is part of me still, but then it was so intense that I could not imagine why anyone ever wanted to leave this island. I am a different person now, so different that sometimes I think it cannot have been me that sailed so reluctantly from England at the beginning of May, 1942.

We were a mixed convoy. There were ships from nearly all the allied nations. Ships of every size, shape and age, but all wearing the same grey war paint. We were escorted by a cruiser and several destroyers, some British and some Lend-Lease American. Over the horizon, we were told, lurked one of our battleships and an aircraft carrier.

Our own ship was the Athlone Castle, one of the newest vessels of the Union Castle line. She had been converted into a troop carrier and now carried about five times her peacetime complement of passengers. Forty-eight of our draft of officers were given bunks in a room rather less than half the size of a Nissen hut. The bunks were arranged in tiers so that we were no more able to sit up in our bunks than a corpse can sit up in its coffin. The rest of the officers slept four to a cabin. We felt far too crowded for comfort, but we were waited on by peacetime stewards and served with peacetime food in the dining saloons. Those of us who visited the men on the lower deck, where the rations were meagre and the atmosphere stifling, realized that no officer had any cause for complaint. Down there the overcrowding was indescribable; nobody suffering from claustrophobia could have survived. Black-out regulations were very strict and all portholes had to be kept shut at night; portholes on the lower decks were never opened.

The draft of officers in which I found myself was not my idea of a fine body of men. Most of them did nothing but sleep, eat, drink and amuse themselves in unimaginative ways, not even bothering to appear for the daily physical training parade. The officers’ lounge in the evening soon became a place to be avoided. I have enjoyed having too much to drink on occasions as much as anybody, but to get drunk every evening in the same place with the same people singing the same bawdy songs seemed to me depressingly monotonous. It certainly did nothing to endear the officers to the troops, whose drink ration was severely limited. Sometimes I could not help wondering how many of the officers on board had been sent to India because their commanding officers wanted to be rid of them. My own C.O. had said he was sorry to lose me. He had been ordered to send some of his junior officers. Why, I wondered, did he choose me? Did he think I was ‘bolshie’? I wished now I had not been so critical of and frustrated by the slowness and inadequacy of our training. How delightful those months of muddle in Lincolnshire and Suffolk now seemed.

In George Borrow, another officer of my battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, I found a kindred spirit. An East Anglian, like his famous forebear, George was slightly built, quiet and studious, with a face like a baby owl. At first sight definitely not the kind of person one would expect to feel at home in the army; an academic, I decided, and not a man of action. I soon discovered my mistake. There was about George a remarkable integrity and sincerity and a wonderful gift of being able to devote himself entirely to what he was doing. This, combined with a phenomenal amount of determination, enabled him to endure far more than most of those who, appeared to be better equipped for warfare. He was also one of the gentlest and least selfish men I have met. Everyone who met him came to like and admire him. Before joining the Army he had spent a year at Cambridge and, as I had spent the same period at Oxford, we had much in common. There was ample time for reading and talking, and I remember that, among other books, Lord Elton’s St George or the Dragon and C.S. Lewis’s The Problem of Pain stimulated much discussion.

We also managed to enjoy some music. One of the officers had managed to bring with him a fine collection of gramophone records which he played to us in the evenings. Perhaps because it provoked such home-sickness for the English countryside, it is his record of Delius’s On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring that I remember best. Some very good programmes were broadcast over the ship’s loudspeaker system and, on the lighter side, we found among the troops much talent for staging amusing variety shows.

Among those on board were a draft of Somersets and Gloucesters who were going out to reinforce a battalion which had suffered heavy casualties in the recent withdrawal from Burma. I met several of their officers and offered to give them a hand as they seemed very overtaxed, while we unattached officers had no duties. This involved me in the censoring of letters. Many of the men wrote at least one long letter a day throughout the voyage, although they knew that there was no chance of posting them until we reached port. It was a sickening chore to have to read the pathetic outpourings of so many sorrowful souls, but for security reasons it had to be done. Sometimes I was overwhelmed by a feeling of utter disgust with a world in which there could be so much misery, and at these times the war seemed nothing but a wretched mixture of evil and suffering, with no gleams of hope. Fortunately my sense of proportion usually reasserted itself quite quickly. I soon realized that I was not expected to try to bear the burden of the whole world’s sorrows.

We had frequent boat drills, the alarm bells usually sounding when I was enjoying the luxury of a bath, so that I arrived dripping and breathless on the boat deck to be greeted by much mirth and the information that it was only a practice alarm.

Freetown was quite as sweltering as everybody always says it is. Because of the risk of infection no one went ashore, but we spent several uncomfortable days lying in the harbour. Much to the disgust of the natives, we were not allowed to throw coins to them when they rowed out in their bumboats as there was a shortage of small change on board. Mercifully the appalling heat was relieved every night we were there by a violent tropical thunderstorm; as soon as it began everyone stripped and rushed on deck; it was like watching some tribal dance to see hundreds of naked bodies leaping about in the blessed cool of the rain, the whole scene vividly lit by flashes of sheet lightning with the hills of Africa forming a spectacular backdrop. Describing our stay in Freetown, I burst into verse:

… You must realizeThe ship was crowded, grossly overcrowded;It carried many times its complementOf bodies; I say bodies purposely,For in that climate you become awareWith emphasis that you are physical;Your bodily being overrides all elseAnd every part clamours for recognition …… During the dayWe lay becalmed in silence, till the sunRelieved us of its pressure. Then we stoodTalking beside the rail of this and that,Of what the future held and what the past,Of things we loved and things we wanted changed(Of those we’d left we spoke not, only thought).Others would sing sweet songs whose very notesBring flooding back a thousand memoriesOf times in England. Thus the cooler airOf evening blotted out the consciousnessOf what and where we were. There was no roomFor most to sleep on deck. We spent the nightTossing in sodden heat and airlessnessUntil we heard the wind, which always cameBefore the morning. Then like souls in hellThat leap up at a glimpse of Paradise,We scrambled to the deck with shouts of joyAnd laughter, revelling in the God-sent rain.The lightning tore the startled air and showedA thousand naked bodies bounding upTo drink delight. We had not been forgotten.

The ship was so crowded that we were spared the ceremonial of crossing the line. Just before we reached the Cape the convoy divided, our half putting into Cape Town and the other going on to Durban. I was watching this manoeuvre with an officer, who knew everything about every ship in the convoy, and we began discussing the progress of the war at sea. He was full of interesting information.

“The crew say they have never been on a trip where there have been so many submarine alarms,” he told me.

“Really?”

“The Jerries are going all out now with their U-boats. You know they have sunk the Queen Mary?”

“No! When?”

“A few months ago.”

“I didn’t hear about it.”

“Well, of course, they will never announce it until the end of the year but it’s a fact.”

For a few minutes we watched our cruiser pass closer than usual and make several runs at top speed through the middle of the convoy. The coast sparkled in the sun and we could see Table Mountain in the distance. Suddenly everyone on deck began to move to the other side of the ship. We followed. It was impossible to reach the rail, but we could easily see what was attracting all the attention. Rapidly overtaking us was the largest and one of the loveliest ships I have ever seen. As she passed us she came so close that anyone who was still in doubt could read her name – Queen Mary!

Before landing at Cape Town we were warned about the notorious District Six, the potency of Cape Bandy, and the colour bar. Before we left, several men from the convoy had been stabbed in District Six and a couple of men from the Athlone Castle who had decided to test the strength of the brandy were carried back to the ship where they remained unconscious for about twenty-four hours. The colour bar was the only thing I did not like about Cape Town. I was not persuaded by the argument that if I were to live there for any length of time I would soon realize how necessary it was, and I objected to being reproved by a white woman for speaking to an elderly black woman in the street, especially as I was only asking the way to the Post Office.

The hospitality was tremendous; every man in the convoy was royally entertained. The South Africans invited us into their homes, took us to see the sights, and to shows, and did everything to make us remember our four days with them as one of the most pleasant times of our lives. After the years of black-out in England, it was a joy to see the lights at night; this meant more to us than the unrationed food and the luscious fruits. Everywhere we met the same genuine friendliness. One day George Borrow and I escaped from the organized hospitality and went for lunch to the Mount Nelson Hotel. The head waiter proved to be an old Sussex man, which was a good start. Before long he had brought us a bottle of wine, a present from a gentleman lunching nearby. We went over to thank him and he at once asked us to dine and go to the theatre with him. We had hardly been talking to him for five minutes when he offered us jobs on his farms if we returned to South Africa after the war. It seemed that the British in South Africa were particularly anxious to lure as many Britons as possible into the country.

Later that day George and I received further evidence of South African friendliness. We emerged from a cinema about midnight to find that it was pouring with rain. We had no raincoat with us and we had to return to the boat, so, seeing what we took to be a taxi standing at the side of the road, we leapt in and ordered the driver to take us to the docks. It was only when we were nearly there that the driver good-humouredly revealed to us that he was a very senior officer in the South African Air Force and that the “taxi” was his private car.

The rest of the voyage was uneventful. We had some rough weather rounding the Cape before we collected the other half of the convoy from Durban. There was a distant view of Madagascar and another magnificent close-up view of the Queen Mary at full speed. Later a number of ships left the convoy to go on to the Middle East. We heard afterwards that the Armoured Division they had on board went straight into action in the Desert.

I was sorry when the trip was over. As we steamed into Bombay on 4 July I tried to feel some of Kipling’s enthusiasm for the place. Many officers did not know what regiment they were to join in India. Soon after we had docked a list was sent on board giving the number of officers required by various units in different parts of the country. We spent a merry half-hour posting ourselves to the ones we thought the most attractive. I chose the unit furthest away from Burma and the Japanese. Our plotting ceased with the arrival of definite posting orders for us all. There were four Royal Sussex Officers on board besides George Borrow and myself. We were all to report at once to the 13th Battalion of The King’s Regiment at Patharia in the Central Provinces. We had heard of the King’s and knew they were a Liverpool regiment, but nobody knew anything about Patharia. Enlightenment was not long delayed.

CHAPTER 2

Training

We did not have time to see much of Bombay as our train left at midday, but we took a short stroll through the streets around the docks, which I afterwards discovered gave a very false impression of the place. The first thing we noticed was that peculiar smell that is found in every village of India: it can best be described as the Oriental version of the English farmyard smell.

We were soon surrounded by beggars, and a host of small children with outstretched hands wailing the inevitable “Baksheesh, sahib”. After you have been in India a while, you manage to ignore all this and stroll along sublimely indifferent to the swarms surging around you. This is a technique which takes time to develop; some of the beggars are so hideously deformed, and all are so pitifully thin, that a new arrival soon succumbs. Later I was told that in certain Indian families children are deliberately deformed in infancy in order to excite more pity, but we were new to India and it was not long before one of us had parted with a couple of annas to get rid of a particularly persistent child. This was fatal. The news seemed to spread in a moment and before long we were surrounded by a clamorous crowd. It took us some time to struggle back to the dock gate.

Meanwhile George Borrow had appointed himself our Cook’s agent. When we arrived at Victoria Station we found him there with all our tickets, baggage and reservations complete. This was typical of George. Without any fuss or bother he would slip quietly away, and when we slower and lazier members of party eventually began to stir ourselves into action, we would find that George had already taken all the action necessary, not only for himself but for us all.

George and I had already become firm friends on the boat, so we shared a compartment on the train. In India there are not many corridor trains, so usually you walk along to the restaurant car for your meal at one halt and return to your compartment at the next. We remembered to lock the doors of our compartment while we dined that evening, but forgot to do so before settling down for the night; the results of this omission became apparent in the early hours of the morning when I awoke from an easy sleep and noticed that the compartment felt rather stuffy. I was in the top berth, so I bent down and switched on the light. There, on the floor, blinking and grinning up at me, were five or six very dirty Indians, all quite happily chewing nuts. For a moment or two I was completely nonplussed; then I reached out and grabbed my revolver which was hanging on a peg. At this they all murmured, “Sahib, Sahib” in deprecating tones and then continued to chew. Happily, while I was meditating on the next move, George woke up. He grasped the situation in a moment, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Return Via Rangoon by Philip Stibbe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Vietnamkrieg. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.