- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of Sheffield

About this book

Covering thousands of years and a multitude of topics, the book tells the story of the development from a group of small agricultural settlements into a town and then a modern city. It covers success, disappointments, miserable periods and glorious episodes that have marked the city's evolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Making of Sheffield by Melvyn Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | A PEOPLED LANDSCAPE: THE AREA BEFORE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NORMAN TOWN OF SHEFFIELD |

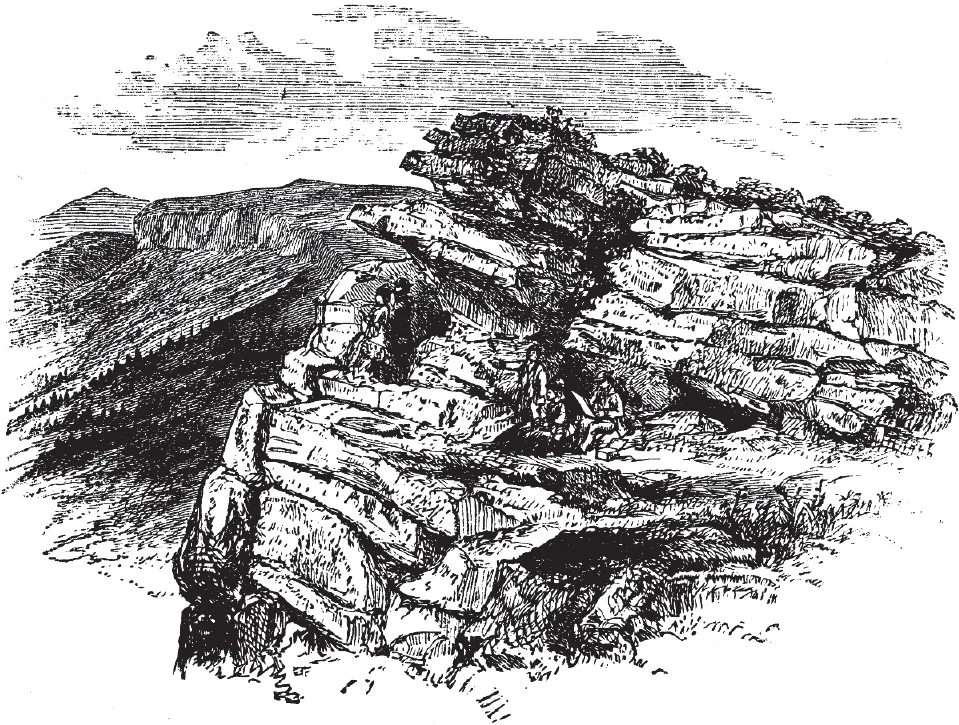

The physical setting of Sheffield is equalled by no other British city. It is enveloped in the west by very extensive tracts of high moorland and upland pasture rising to nearly 550 metres (more than 1800 feet), all within the modern city boundaries. From this lofty surround a large number of rivers and streams, not only the Don and its five major tributaries, the Little Don, the Loxley, the Rivelin, the Porter and the Sheaf, but a myriad of minor brooks and becks such as Ewden Beck, Blackburn Brook, Limb Brook, Moss Brook and Wyming Brook have cut their courses, leaving deep valleys, many still wooded and semi-rural in their western and southern upper and middle courses. Even further east there are deep valleys, as in the Sheaf valley at Beauchief, and prominent edges and hills, as at Brincliffe Edge and Wincobank Hill. Beside the River Rother in the far south-east at Beighton the land is no more than 40 metres (about 130 feet) above sea level. The modern metropolitan area is built on a series of escarpments and hills and in the intervening valleys.

A nineteenth century engraving of Stanedge. Sheffield and Neighbourhood, Pawson & Brailsford, 1889

The first inhabitants: hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic

Before 10,000 BC this dramatic landscape was roamed by a small population of hunter-gatherers, the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) people whose shelters were crudely constructed of timber and skins or in caves and whose tools and weapons were of stone or bone. They survived by hunting the ‘big game’ that lived in the area – animals such as bison, horse and red deer in the warmest periods of forest vegetation and mammoth, woolly rhinoceros and reindeer when the climate deteriorated and tundra conditions prevailed with only moss, lichens, coarse grass and low, stunted bushes to sustain the animal populations. In the severest climatic periods, sometimes lasting for tens of thousands of years the ground was permanently below moving ice sheets and the human population left the area altogether, only to move northwards again as climatic conditions ameliorated. The human population of the local area in the Palaeolithic period would have been very small with each small group developing a cycle of seasonal movements over a well-known territory following the herds of animals they hunted. Ice movement and the associated scouring of the landscape have removed a great deal of archaeological evidence but Palaeolithic tools and weapons have been found to the east and south-east of Sheffield in the river gravels of the Trent valley and in Deadman’s Cave in Anston Stones wood on the Magnesian Limestone east of Rotherham and more importantly in the caves at Creswell Crags in North Derbyshire.

Hunter-fisher-gatherers of the post-glacial woodlands

Rising temperatures 12,000 years ago resulted in the melting and shrinking of the most recent glaciers and ice sheets which led to a rise in sea levels, and by about 6,000 BC, in the creation of Great Britain as an island separated from the continent of Europe. The rising temperatures also resulted in the thawing of frozen ground and, most importantly, in a gradual change in the vegetation culminating, by about 7,000 BC in a more or less continuous tree cover as species moved in on the wind and in the droppings of birds and animals from those parts of Europe that had lain beyond the grip of ice and freezing conditions to form the primaeval forest called by woodland historians the ‘wildwood’.1

Two interesting glimpses of the fully developed wildwood in the local area come from pollen analysis and the remains of fallen trees subsequently buried below peat deposits. Conway (1947) and Hicks (1971) made studies of pollen on the moorlands in the western part of the city and suggested that by 4,000 BC the area was covered by a mixed oak forest with the canopy broken by areas of damp heath and swampy areas with alder and birch.2 More recent studies in the Humberhead Levels to the east of Doncaster using the evidence of both pollen analysis and buried trees have suggested that before the drowning of the wildwood there, between 3,500 and 2,500 BC, there was on Thorne Moors a mixture of marshy woodland in the wettest areas made up of birch, willow and alder, deciduous woodland dominated by oak on the clay-silts and native pine forest on the sands. On the sands and gravels of nearby Hatfield Moors the wildwood consisted of native pine woodland with oak locally present and patches of more open heathland.3

Pollen analysis suggests that there were permanent glades of varying sizes scattered throughout the wildwood which would have been grazed and kept relatively treeless by wild cattle, swine and red deer.

As the environment changed from tundra to forest after 10,000 BC the surviving human population gradually began to subsist on smaller prey (mammals, fish and birds) of forest, marsh, river and lake and the more abundant fruit, nuts and roots. Mammals included wild cattle, red deer, horse, wild pig, bear and beaver. The bow and arrow had been invented by this time and it was perfectly fitted for silent and patient hunting in a forest environment.

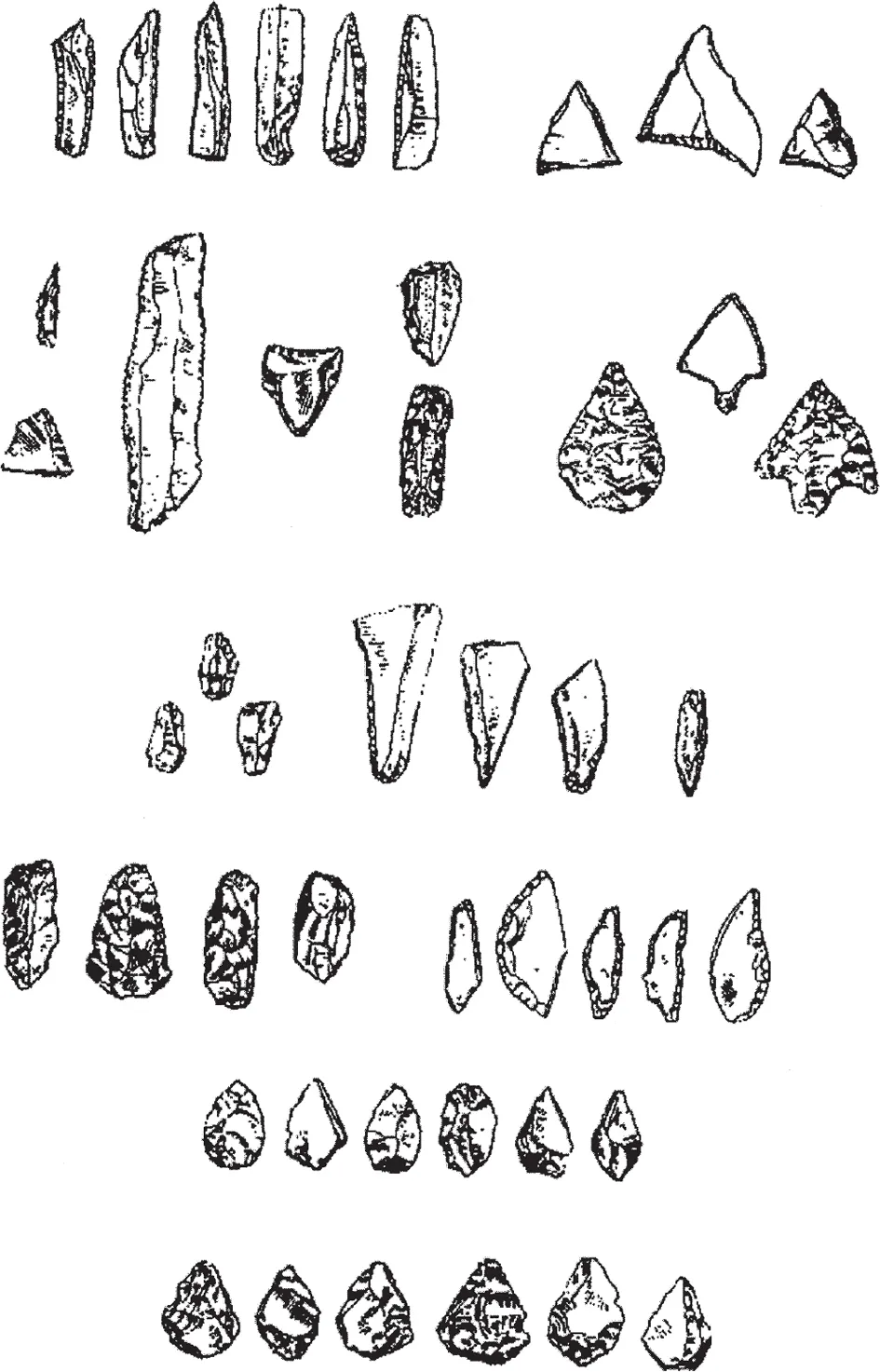

The impact of these hunter-fisher-gatherers, known as the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) peoples, on the natural environment, like their predecessors, would have been negligible. All they have left behind in the Sheffield area are their tools and weapons. Finds have been made on the gritstone moorlands to the west of the built-up area of Sheffield where they have been preserved beneath peat deposits and then revealed as the peat has eroded. Finds have been rarer further east because of disturbance by later cultures and burying under residential and industrial developments, but important finds have been made at Bradfield, Deepcar and Wincobank within Sheffield and at Hooton Roberts and Canklow in Rotherham. At Deepcar, for example, what appears to have been a temporary camp beside the River Don, where flint tools had been prepared, yielded more than 23,000 artefacts (including debris from working flints). There were signs of a shelter, possibly a windbreak, around three hearths. Thousands of Mesolithic tools and weapons from Bradfield and Hooton Roberts were collected by ‘field walking’ by Reginald Gatty, the Rector of both places between 1869–1888 (Bradfield) and 1888–1914 (Hooton Roberts). As described by himself his technique was on a spring morning ‘to enter the farmer’s gate and follow the toiling horses. It is not long before a ray of sunlight flashes on a flint flake, and I stoop, and capture my prize’.4 Part of his collection is in Weston Park Museum in Sheffield and Clifton Park Museum in Rotherham.

Mesolithic flint tools and weapons collected by Reginald Gatty in Bradfield and Hooton Roberts. Reliquary and Illustrated Archaeologist, January, 1900

The most characteristic artefact of the late Mesolithic period is the microlith, i.e., a very small worked stone, most commonly flint or chert (flint-like quartz). A microlith is either in the shape of a very small arrowhead or a barb, and these would have normally been fitted into a wooden shaft to make a multi-faceted arrow, harpoon or spear suitable for hunting.

In the late Mesolithic period hunting became more intensive and the forest environment appears in some places to have been managed by felling and burning the wildwood to entice deer into areas of new, highly palatable growth. This development foreshadowed the later domestication of pigs, sheep, goats and cattle.

The first permanent settlers and farmers

While the Mesolithic peoples of the Sheffield area were following their hunting-fishing-gathering lifestyle a revolution was taking place in the Middle East and Mediterranean Europe. This was the development of agriculture from about 8,000 BC accompanied by pottery making and weaving. This agricultural revolution involved the domestication of pigs, sheep, goats and cattle, the breeding of horses, the invention of ploughing and the growing of cereals, and the eventual change from a semi-nomadic existence to one where settlement sites were occupied on a more or less permanent basis.

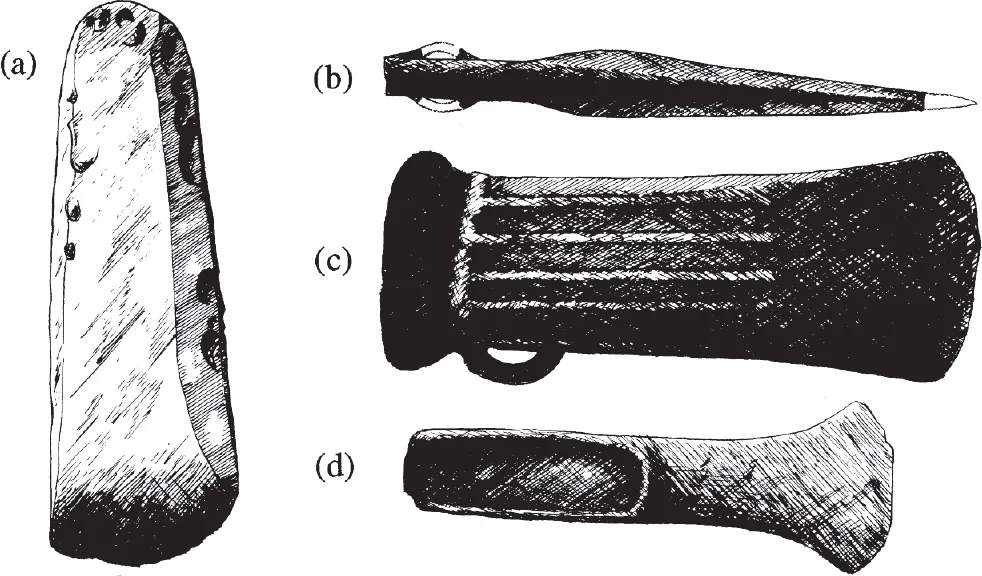

These innovations spread throughout Europe through farmers colonising new lands and hunter-gathers adopting them through contact with farming communities and they reached the British Isles between 3,000–4,000 BC. Colonists must have introduced cereals and sheep because these are not native to Britain. At first farmers and hunter-gatherers must have lived side by side but by about 3,000 BC pastoral farming had replaced hunter-gathering as the main means of subsistence in the southern Pennine and sub-Pennine areas This was the beginning of what is called the Neolithic (New Stone) Age. But despite the ‘Neolithic Revolution’ tools were still of stone, although finished more expertly and the wide range of igneous and metamorphic rocks employed suggest strongly that they were often acquired through long-distance trading. Unlike neighbouring Derbyshire no Neolithic settlements or sacred monuments have been found in the Sheffield area, and the presence of this culture in the area is only known from the chance finds of tools and weapons.

(a) Neolithic polished stone axe, Wharncliffe; (b) Bronze spearhead, Stannington; (c) Bronze axe, Wybourn estate; (d) Bronze palstave, Rivelin valley.

A series of later farming cultures succeeded the Neolithic in the rest of the prehistoric period and beyond into the succeeding period of Roman rule. The Bronze Age which succeeded the Neolithic probably began in the Sheffield area about 1650 BC. Although stone continued to be used for tool and weapon manufacture, this culture marked the beginning of the use of smelted metals. Bronze is an alloy made by smelting copper with tin. Finds of bronze tools from this period include axes, daggers, spearheads and decorative pins recovered from burial cairns on the Millstone Grit moors or as chance finds. Other features associated with the Bronze Age include stone circles associated with burial, for example on Broomhead, Burbage and Totley Moors, a few funerary urns and rocks with cup-shape hollows and incised circles called cup and ring markings.

The Bronze Age was succeeded in South Yorkshire by the Iron Age about 700 BC. Smelted iron tools took the place of those made of bronze but this is likely to have been a slow process, distant as the area was from the centre of technological progress in the south of England. The major archaeological feature of the Iron Age still surviving in the present landscape is the fort. Each fort would have been surrounded by a farmed countryside whose inhabitants would have owed allegiance to a local chieftain and would have looked towards the fort for protection in times of unrest. Seven and possibly eight such forts survive in South Yorkshire, two of them (Wincobank and Carl Wark, although some doubt still exists about the dating of the latter) within Sheffield City boundaries and the site of a third which formerly existed in Roe Wood is well known.

Wincobank Iron age hill fort: (a) plan; (b) external ditch. Joan Jones

The Wincobank hill fort occupies a commanding position overlooking the lower Don valley near the present day boundary between Sheffield and Rotherham. It lies only at 160 metres (525 feet) but as the land slopes away steeply in all directions its presence is felt for several miles around. Wincobank Hill is a hog’s back (a long narrow hill) of Coal Measures sandstone bounded on the north-east by the valley of the Blackburn Brook and on the south-west by a minor stream at Grimesthorpe. The result is a dry, easily defended hilltop with good views all around. Today the grass-covered rampart at Wincobank is more or less complete but the ditch and outer bank are absent along most of the western side of the fort and along the northern part of the eastern side. Excavations by Sheffield City Museums in 1899 and 1979 have shown that the rampart was originally made as a stone wall several metres thick bonded together by timbers. The stone rampart would almost certainly have been topped by a palisade. When the rampart was excavated it was found that the timbers had been burned, suggesting that the fort was destroyed by fire. The charcoal from the burnt timbers gave a carbon date suggesting that the trees had been felled to construct the fort about 500 BC.5

During the succeeding Roman period (AD 43–410) the area within the modern Sheffield City boundaries was not occupied by the Romans and the nearest Romans were found in the Peak District to the south, and at the fort at Templeborough just beyond the Sheffield boundary in Rotherham, first established as a timber fort in AD 54 and rebuilt in stone about AD 100. During the Roman period the local British population would have been engaged in farming activities, slow population growth would have taken place, settlement would have continued to spread and there would have been considerable impact on the wildwood as new sites were occupied for cereal growing, then abandoned and kept as open...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Peopled Landscape: the area before the establishment of the Norman town of Sheffield

- Chapter 2: The early Town of Sheffield and its Surrounding Countryside

- Chapter 3: ‘The Custody of the Scotch Queen’: Mary, Queen of Scots, in Captivity in Sheffield

- Chapter 4: The Cholera Epidemic of 1832

- Chapter 5: ‘Right Sheffield is Best’: The history of Sheffield’s Light Steel trades

- Chapter 6: Steel City: The Rise and Decline of the Heavy Steel and Engineering Industry in the Lower Don Valley

- Chapter 7: Eminent Sheffield Victorians

- Chapter 8: Edwardian Sheffield in Picture Postcards

- Chapter 9: Postscript: the Shaping of the Modern City

- Notes and References