![]()

Part One

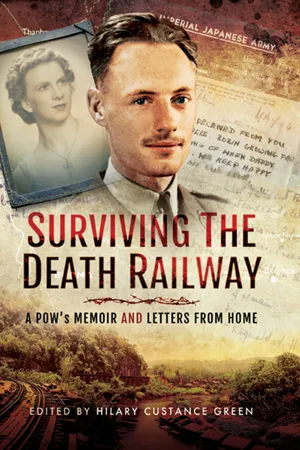

Barry, Phyllis and 27 Line Section

Phyllis Bacon in the City of London, 1937.

![]()

Chapter 1

Britain: Spring 1937 to Spring 1941

After the ball, Barry and Phyllis

In 1937 Barry, a 21-year-old student at King’s College Cambridge, bought tickets he could not afford for a May Week ball. He left the ball at 6.00am and returned to his rooms feeling a little dispirited. Then, he remembers:

I went across the road into the Copper Kettle Café for a reviving cup of coffee and allowed myself a little chit-chat with the pretty waitress who served me. The next five minutes changed my whole life.

A young woman in a plain coat and skirt whose face looked faintly familiar came into the café and the waitress, who seemed to be a friend of hers, said ‘Phyllis dear, please take this drunk off my hands’. So Phyllis took a cup of coffee and sat down at my table. I soon realised that she was Phyllis Bacon whom I had noticed several times on the stage in plays by the Footlights or the ADC [Theatre] but had never actually met before. We got talking (I was not drunk just rather miserable and very tired). We walked back across to King’s and had another coffee in my rooms. She told me that she had just completed her three years at Newnham in English Lit and Lang.

Over the next two years Barry and Phyllis visited each other’s homes and Phyllis stayed over at Catterick Camp, where Barry was on the Young Officers training course. They soon became lovers, and Barry’s ingenuity was often tested in finding suitable berths without alerting disapproving relatives – not always successfully. They had one favourite stopover, the Wensleydale Heifer, a small pub in West Witton, on their route between London and Catterick.

In 1938, with Barry aged 23 and now a commissioned officer in the Royal Corps of Signals (Royal Signals or RCOS), he and Phyllis became engaged. On 29 July 1939, with war a near certainty, they were married.

Barry (Lancelot Barton Hill Custance Baker, or Barton to his family) was born in Penang, Malaya, in 1915. This, like so many twists in life, was about to have a major impact on his future. He had two younger brothers, Alan and John. His parents, though nearing retirement, were still in the Malayan Civil Service in 1939 and not able to attend his wedding.

From an early age Barry showed an inclination for engineering and enterprise, another factor that was to have an immense impact on the next few years of his life. As a child he created sails for a boat on his great aunt’s sewing machine, he constructed his first lathe aged 12 and ran a commercial fudge-making enterprise at school, Marlborough College. At Cambridge he was an indifferent but wide-ranging scholar. He studied Natural Sciences, Maths and Physics, then Modern Languages, and finished up with a pass degree in Military Studies.

Barry and Phyllis at their wedding reception, the Langham Hotel, 1939.

Phyllis, born in London in 1914, grew up to be passionately interested in the stage, but she was also the daughter of James Bacon, a man of strong Methodist principles. When Phyllis was offered a place at Sadler’s Wells drama school, James turned it down without telling her. She was sent to the Institute of Industrial Psychology for career assessment and they advised her to take up a practical subject – ideally Domestic Science. However, Phyllis, a bare 5ft 2in, was cut from the same cloth as her father, with strength of character and a social conscience. In a fit of rebellion she gained a place at Newnham College, Cambridge and completed her degree in English – but spent every spare moment of her student life acting.

Honeymoon and war

In August 1939, Barry and Phyllis set off on a blissful and long-remembered honeymoon in a little pension on the Brittany coast near Nantes. War brought this to an abrupt end:

Near the end of our fortnight honeymoon I received a very peremptory telegram from my CO (Commanding Officer) ‘RTU Mob’. So we set out immediately to ‘Return to Unit’ for Mobilization.

Barry, a fluent French speaker, had been all set to travel with an advance party to France soon after the outbreak of war. However, a young Canadian, driving on the wrong side of the road, ran head-on into Barry on his motorbike. Barry suffered a cracked skull and concussion, he was severed from his unit and parked in office jobs over the many months of his recovery.

Phyllis in costume, 1930s.

Phyllis on honeymoon in France, August 1939.

Meanwhile, in Malaya, Barry’s parents, Barbara and Alan, were about to retire from the Residency in Kelantan. Alan had been in the Malayan Civil Service for thirty-two years and British Advisor to the Sultan since 1930. A letter from Barbara gives an insight into pre-war Malayan colonial life in its hectic, multicultural late stages. It is also sets the scene for the world into which so many British soldiers were flung eighteen months later:

1 February 1940, from Barbara (Kota Bharu, Malaya) to Phyllis and Barton (Barry)

My darling Phyllis and Barton. We have only one week more before leaving S’Pore and it will be a busy one. Derek came to a very early dinner and we went to an amateur show got up by His Highness’s brother for the Malaya Patriotic Fund … That night His Highness gave us a Farewell dinner at the Balai (orders and decorations). There were about sixty people there and the Sultan made an absolutely sweet speech about Alan and me and then gave Alan a copy on vellum in a silver casket on a silver dish of old Malay silver and to me he gave a most lovely silver dish that is at least a hundred years old. He told me that he had never done this for any other British Advisor. We were deeply touched and Dad made a very good speech in Malay. After dinner we all watched a Mahjong, a sort of Malay play interspersed with Siamese, Javanese & Malay dances, most interesting and the surroundings were beautiful because at the Balai the crowd (women and children) are allowed to come in and watch and they all wear their gayest clothes. It makes it very hot but lovely to look at. That night we did not get home until 1 o’clock. Next morning we had more music, the Malays came and Truda and Charles played the piano which he does really well and in the afternoon Dad and I had to go to a tea party at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce where more speeches were made and he was presented with an address in a silver frame … We then hurried home and took Bentley and Truda for a short walk.

Bentley, according to Barry’s memoirs, was a Great Dane with a taste for eating the local goats – which was his eventual downfall.

The letter continues:

That evening we had Derek and the three Malay District Officers to dinner and after dinner ten more people came and we gave our final concert …

On Monday morning all our guests departed, but it was a busy day. I had a St John meeting at 12 to hand over my secretaryship and in the afternoon we went to a farewell tea at Pasir Mas and in the evening ate khuzi with Tengku Sri Akar and many other friends and then went to the pictures, and yesterday we motored to Krai 48 miles up river by launch to lunch with a very old friend. We got back exhausted for tea. Today we lunch with the Indian community and then go to Krai again for the evening for a Farewell at the club …

Only a moment now to thank you for your dear letters and say that we will love to stay with you! As to washing up, it is neither here nor there.

No time at all but send our dear love. Mum

Barbara and Alan Custance Baker with Great Dane, Bentley.

Back in Britain, Barry was finally deemed by the army as ‘fit for everywhere’ but found himself still at a desk. In the June of 1940 he fetched up at Harnham Camp, near Salisbury:

My arrival at Harnham was soon after the retreat of the BEF [British Expeditionary Force] from Dunkirk and everything was in a great muddle. We were then, mid 1940, living under constant threat of invasion. The Air Battle of Britain was happening all around us and the Blitz on London soon started up, but Salisbury and Harnham were not significantly bombed.

Meanwhile, Phyllis, now pregnant, had been living with her parents, James and Lilian, at the White House, Great Missenden, and Barry visited whenever he could. With the London Blitz hotting up, they decided Phyllis would be safer in a cottage in Teignmouth in Devon, which, unlike nearby Plymouth, was never bombed.

During the heavy bombing period of 1940–41 Barry became responsible for the organization of units desperately keeping signals communications going in the hard-hit coastal areas. He would send Line parties or whole sections out:

… to patch up some kind of temporary telephone communications for the Port Installations and the AA guns along the coast. I went to both of the major targets, Portsmouth and Southampton, to see how our linemen were getting on. These towns, after an air raid, showed as much devastation as London docks, yet they carried on with their jobs as Naval Bases and I like to think that our linemen materially helped them to do so. Two of my visits coincided with actual raids, which were very reminiscent of conditions in Singapore a year later though of course I did not realize that at the time.

The linemen had to work on, raids or not, often patching in to an overhead telephone route. If a telephone pole was knocked over, a lineman would climb up one of the still standing poles, joint on a section of field cable to the broken ends of the wires and lead it, either suspended or along the ground, to the next standing pole and reconnect it to the existing open wires – exposed and hair-raising work.

Half way through this period of heavy bombing, on 17 December 1940, Phyllis and Barry’s son, Robin, was born in Teignmouth hospital.

27 Line Section created

A wartime army has to adapt and change its spots rapidly; it becomes a different beast from the carefully planned establishment of peacetime. In the spring of 1941, Barry was summoned by his CO, Colonel Bury, to discuss a new job. He had studied Barry’s file and wanted him to take over a new Line Construction Section that was being formed mainly from members of the Glasgow Post Office Special Reserve Unit (or SR). This was similar to the Territorial Army (TA), but largely made up of technical tradesmen. As they were mostly pre-war reservists they could, apparently, be considered volunteers. It became clear during this interview that the destination for this unit was probably Malaya – Barry’s country of birth. The gist of the interview amounted to this:

Would I like to have the Section and take it wherever? It was larger than a normal Line Section, 72 (later 69) all ranks, a Captain’s command, with a Subaltern under him. It sounded ideal but I asked for a day to think it over (and to consult my wife). At that time in the War, the Far East was peaceful and not involved in warfare, wives and families were still with their serving husbands. I confidently believed that Phyllis would probably be allowed to come o...