- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From Bruneval to North Africa, from Normandy to Suez, by parachute and glider the men of the Airborne Forces have gone by air to battle. But their activities have by no means been confined to purely airborne operations- the Special Air Service performed prodigies of valor behind the German Lines in the Western Desert and Italy; the Glider Pilot Regiment fought beside their infantry comrades in Normandy, at Arnhem and across the Rhine. Their post-war successors, maintaining these traditions, have stood between Jew and Arab in Palistine; fought and sweltered in the jungles of Malaya and Borneo; sweated in the Persian Gulf and the Radfan; chocked on the summer dust of Cypriot roads; tasted the grit and sand of Egypt and Jordan in their mess mess tins; spent more then a decade facing terrorist ambush, bombs and bullets in Northern Ireland; experienced subzero temperatures and biting arctic winds in the South Atlantic and 'tabbed' across the Falklands to spearhead victory in 1982. Now should the aircrews who flew them be forgotten, or the air supply dispatches who maintained them, or the units who supported them. With well over 100 photographs and illustrations this book is a comprehensive single-volume history of the Airborne Forces. Accounts are given of the airborne actions fought by the British Army, whilst the development of the parachute assault and the use of the glider-borne troops can be followed from their infancy to the massive coup de main technique employed in the Rhine crossing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Red Devils by G.G. Norton, Brian Horrocks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'armée et de la marine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

| Chapter | 1 | Formation, Development and Early Raids |

| 2 | Middle East, 1942–3 The Classic Role | |

| 3 | Special Air Service | |

| 4 | The Far East I | |

| 5 | The Far East II | |

| 6 | Normandy | |

| 7 | The South of France: Greece | |

| 8 | Arnhem | |

| 9 | Arnhem Aftermath | |

| 10 | Across the Rhine: Norway Again | |

| 11 | Java | |

| 12 | Palestine 1945–8 | |

| 13 | Egypt 1951–4 | |

| 14 | Malaya 1955–7 | |

| 15 | Cyprus 1956 | |

| 16 | Suez 1956 | |

| 17 | Jordan 1958 | |

| 18 | Cyprus Again 1964 | |

| 19 | The Persian Gulf 1961–7 | |

| 20 | The Radfan 1964 | |

| 21 | Confrontation: Borneo 1965 | |

| 22 | British Guiana 1965–6 | |

| 23 | Aden 1967 | |

| 24 | Anguilla 1969 | |

| 25 | Northern Ireland 1969–83 | |

| 26 | The Falklands 1982 | |

| 27 | Summing Up | |

| Appendix | A | Chronology of British Airborne History |

| B | History of No. 38 Group, RAF | |

| C | Air Re-supply | |

| D | Casualties, Airborne Forces, 1941–45 | |

| E | The Museum of Airborne Forces | |

| F | Important Dates in British Airborne History | |

| G | The Regimental March | |

| Index |

Chapter

1

Formation, Development and

Early Raids

‘We ought to have a Corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops’Winston Churchill, June 1940

THERE IS something characteristically British about the origins of Airborne Forces — except, perhaps, for the fact that it was not we who first thought of the idea. That honour is shared equally by the Russians and the Germans, both of whom were developing this type of warfare as early as 1936; but even though General Wavell himself saw the former drop 1,500 men, with machine guns and light artillery, during the summer manoeuvres that year, and reported that ‘if he had not witnessed it, he would not have believed such an operation possible’, his testimony roused no enthusiasm for similar units in Britain. And when, in May of 1940, the Germans employed parachute soldiers and glider-borne troops with such devastating effect during their blitzkrieg on Western Europe, and it seemed that there might be something of value for us in this type of warfare, all that happened was that, as a result of a conference at the Air Ministry, it was stated that ‘it has been decided to establish a parachute training centre’, and the War Office detailed Major J. F. Rock, RE, ‘to take charge of the military organisation of British Airborne Forces’. That was about the extent of his brief. ‘It was impossible’, Major Rock confided, ‘to get any information as to policy or task’.

From this indeterminate beginning, and largely through the pioneering work of Major Rock and his Air Force colleagues, Wing Commander L. A. Strange, Wing Commander Sir Nigel Norman and Squadron-Leader Maurice Newnham, Airborne Forces grew and thrived. They received a timely boost from Churchill’s minute, quoted above. Its demand for a powerful offensive force—at a time when most people in Britain were concerned only with defence—was a defiant and far-sighted move that was to justify itself many times over as the tides of war changed. As a result of these separate initiatives, the Central Landing School was set up at Ringway Airport, near Manchester, on June 21; and exactly a month later men of No. 2 Commando were dropped, for the first time, from converted Whitley bombers. Central Landing School, which in August 1940 became Central Landing Establishment (and later Airborne Forces Establishment), belonged to the RAF; and it was some time before the duties and responsibilities of the two services were worked out. In the outcome, the RAF was in charge of parachute training, and the Army of the military requirements of airborne warfare.

Parachutists dropping from converted‘Whitley’ bombers, August 1942. (Courtesy Imperial War Museum.)

Even with Churchill’s backing, the call for ‘5,000 parachute troops’, with all that that entailed in the way of equipment, was not one that could be easily met in the troubled second half of 1940. For, at the worst possible moment, we were trying ‘to cover in six months the ground the Germans had covered in six years’. We had neither the aircraft nor the parachutes: and perhaps more important still we were totally without first-hand knowledge or experience. Everything had to be designed., worked out and built from the beginning. Even such elementary matters as the best way to drop parachute soldiers from the aircraft—through a hole in the floor, which was quite likely to knock their teeth out, or through a door in the fuselage—were a matter of trial and error. No. 2 Commando was transferred to parachute duties to become No. 11 SAS Battalion, and gradually the novel and difficult techniques of parachute warfare were perfected.

Early experiments in converting bomber aircraft to parachuting. This picture shows an RAF instructor having just jumped ‘through the hole in the floor’ of an Albermarle aircraft in 1940. (Courtesy Imperial War Museum.)

One small example was the elimination of all the bulky padded clothing (copied from the Germans) of the early experiments, and its replacement by normal fighting uniform together with the parachutist’s smock. Another was the development of the ‘X’ Type ‘statichute’ which opened automatically and offered, within limits, a degree of control in flight; and the dropping of men in sticks of ten. Simultaneously, the amount of equipment that a parachustist could carry with him on a drop was being worked out empirically, and was steadily increased.

And so, at a time when the Germans were preparing for their most dramatic airborne stroke—the capture of Crete in May 1941—the British were mounting their first small experimental operation. At this time, as for many years to come, parachute units were made up of volunteers from infantry regiments; and it was reported that by February 1941, these men were growing tired of training and inaction and were applying to go back to their own regiments. Then the rumour of impending action got around; there were no more applications; and when volunteers were called for, every officer and man of the 500 in the battalion stepped forward. But for that first, tentative employment of British airborne forces, only seven officers and 31 other ranks were needed.

Typical German Airborne soldiers (Fallschirmjäger). These were part of the group which rescued Mussolini, after his arrest by the Italians, in September 1943. (Courtesy Imperial War Museum.)

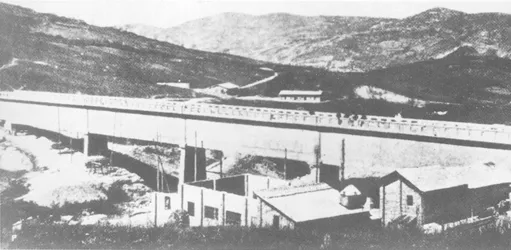

Their objective was the Tragino aqueduct in southern Italy. The supply ports of the Italian Armies campaigning in North Africa and Albania were Taranto, Brindisi and Bari, in the arid province of Apulia. They relied for their water on the ‘Acquedetto Pugliese’, an extensive pipeline from the River Sele through the Apennines, and it was believed that cutting the supply would cause serious dislocation in these ports. The vulnerable points in the pipeline lay inland, and since a seaborne raid was impracticable, and bombing had proved ineffective, the newly-fledged parachute troops seemed to be the obvious, and indeed the only means. A force of 38 men from the nth Special Air Service Battalion was picked, with Major T. A. G. Pritchard, RWF, in command, and Captain G. F. K. Daly, RE, to lead the demolition party. They were to drop just north of the aqueduct from six Whitley aircraft of No. 91 Squadron, as two more made a diversionary bombing raid on Foggia. HM Submarine Triumph was to rendezvous near the mouth of the River Sele on the night of February 15–16 to bring them home.

Tragino Aqueduct. This picture, the only one which existed for planning purposes, was in fact taken in 1928 when the aqueduct was built. Some unfinished buildings, the workmen’s huts and scaffolding can be seen. (Courtesy Imperial War Museum.)

After intensive training with mock-ups and models, the party assembled in Malta. The aircraft took off at dusk on February 10, arriving over the target three hours later. In the full moon dropping casualties were light, but, due to technical faults, two aircraft failed to drop their containers of arms and explosives. A third, carrying the main demolition party with Captain Daly, dropped two miles away in the next valley. Night navigation to these fine limits was still somet0hing novel; so the drop, over 400 miles from base, was remarkably accurate.

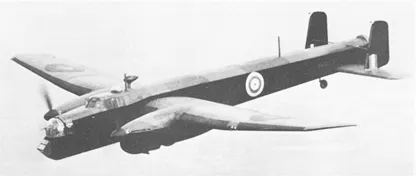

The Armstrong Whitworth ‘Whitley’. This pre-war heavy bomber was soon declared obsolescent and adapted for parachute duties. Though difficult to use—the narrow fuselage was very cramped—and could only carry a ‘stick’ of ten men it performed yeoman service in the early days. Aircraft of this type carried troops on the first two British airborne operations of the war — Tragino Aqueduct and Bruneval. (Courtesy Imperial War Museum.)

The force was short of arms, explosives, its senior RE Officer and five sappers. Second Lieutenant A. Paterson, RE, assumed command of the demolition and sufficient explosives were found to destroy a main Aqueduct pier and a bridge over the nearby River Ginestra. By 3 am on February 11, the waterway was effectively breached, and the force split into three groups to rendezvous separately with the submarine. After various adventures, all of them were captured by the next day — a misfortune that might have been mitigated for them had they known that the submarine had been unable to keep the rendezvous.

The raid was a success, but the damage was soon repaired, and its military effect was negligible. Nevertheless, it was all useful experience, both for the development of parachute equipment and aircraft, and for future operations. But it was just over a year before the secon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents