- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

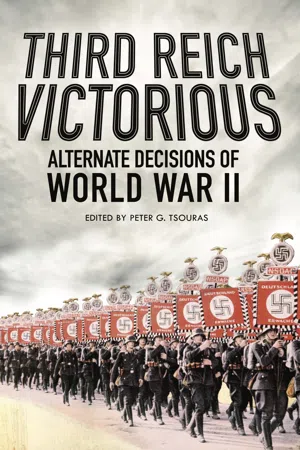

About this book

This book is a stimulating and entirely plausible insight into how Hitler and his generals might have defeated the Allies, and a convincing sideways look at the Third Reich's bid at world domination in World War II. What would have happened if, for example, the Germans captured the whole of the BEF at Dunkirk? Or if the RAF had been defeated in the Battle of Britain? What if the U-Boats had strangled Britain with an impregnable blockade, if Rommel had been triumphant in North Africa or the Germans had beaten the Red Army at Kursk? The authors, writing as if these and other world-changing events had really happened, project realistic scenarios based on the true capabilities and circumstances of the opposing forces. Third Reich Victorious is a spirited and terrifying alternate history, and a telling insight into the dramatic possibilities of World War II.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Third Reich Victorious by Peter G. Tsouras in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE LITTLE ADMIRAL

Hitler and the German Navy

Wade G. Dudley

Introduction

We are the sum of our experiences. Change any of those experiences, and you change the person. Change the person, and you may just change the world. Make that person a young Adolf Hitler, and things do get interesting...

An undying enmity, 1914-19

By early 1914, the highly militarised states of Europe needed only a spark to precipitate war. Between universal conscription and a naval arms race of staggering proportions, few German-speaking young men could have doubted that their opportunity for glory would soon be upon them. Yet, it seemed that fate would deny at least one ardent, neophyte warrior the chance to validate his manhood. Twenty-five year old Adolf Hitler attempted to join the army of his native Austria in February – the army rejected his application.

Failure was not unknown to the brilliant but erratic Hitler. He had failed to gain his certificate from secondary school, failed in numerous odd jobs in and around Vienna, and failed as an aspiring artist. This time, a desperate Hitler determined to succeed. Using the last of his money (failure had also led to poverty and hunger), he purchased a train ticket for Bavaria, intending to enlist in a Bavarian army corps. Fatefully, Hitler shared a bench with Stabsoberbootsman (senior chief boatswain) Günther Luck, returning to active duty from family leave. The garrulous Luck, impressive in his dress uniform, regaled Hitler with stories of the Imperial German Navy’s rapidly expanding Hochseeflotte (High Sea Fleet). As Luck explained, ship after ship sliding down the ways meant rapid promotion for any young man intelligent enough to grasp it. The Stabsoberbootsman must have been an impressive, convincing, and somewhat generous man, for Hitler accompanied him (at Luck’s expense) to the German port of Kiel. There, with the support of his new mentor, the Austrian enlisted in the German Navy.

After a brief period of basic training, Hitler found himself assigned to the light cruiser Wiesbaden, on which Günther Luck served as senior petty officer. In a revealing letter to his wife, Luck wrote about the young seaman’s brilliance and desire to learn, and about the one thing that Hitler had to un-learn, as well:

‘He is an astounding young man, and reminds me of our poor Rudie [Luck’s son had been killed in a tragic accident aboard the battleship Posen a year earlier] in both appearance and the desire to learn. He saw a picture of our boy on my desk; now he wears that silly moustache like Rudie wore, and he reads, he reads constantly. He devoured my technical manuals in the first month on board, and asked for more. I told him to see his division officer, and was surprised to hear him mutter, “But he is a damn Jew.”

My darling, where do our children learn these things? We are a nation surrounded by enemies; we are sailors who constantly battle the sea for our survival. If we hate ourselves, what is left for our enemies but an easy victory? If we let race-hatred divide our crews, will we not founder and drown? I explained this to Adolf, I reasoned with him, and I threatened to box his ears – he never had a real father to do that for him, you know – if I ever heard such words again. Then I took him to see his lieutenant and arranged for Adolf to borrow naval histories. Privately, I explained the boy’s prejudice, and asked the officer occasionally to discuss the books with Adolf.

Still, I worry. He will become a man of strong convictions, strong hates, strong loves. I can only hope that the war which I feel will soon be upon us will focus that hate away from good German citizens and toward our true enemies.’1

Hitler thrived in his new environment. Hard work, naval discipline, and the encouragement of his mentor each played their part in a true seachange. Hitler discovered a capability to lead others. Between charisma, rapidly developing knowledge of seamanship, and the support of Günther Luck, he quickly rose to the rank of Unteroffìziere-maat (petty officer). Perhaps more importantly, he developed a fanatical devotion to the twin institutions of the Imperial Navy and the German Empire. A voracious reader of naval history and theory when off duty, Hitler often shared those theories with his men. They, in turn, affectionately called him ‘unser kleine Admiral’ (‘our little admiral’), and vowed to follow him anywhere - as long as it led to a tavern in Kiel, of course.2

After the beginning of the Great War in August 1914, the talk of every mess in the German Navy centred upon the British fleet. The news from abroad, though not unexpected, was bleak. Within months, Great Britain had swept the seas clean of German surface units, and the few German successes did not balance the list of lost ships and forever absent comrades. Worse, the Royal Navy maintained a distant blockade of the Baltic, denying Germany imports, particularly the nitrates needed to fuel its munitions industry and as fertiliser for its agriculture. If the war continued (and the deadlock in France showed little change as the months dragged onward) then Germany faced a harsh choice – munitions or calories, feed the guns or feed the people.

Of course, if the Imperial Navy could force Great Britain to relinquish its blockade, that choice need not be made. But, despite its aggressive building programme in the early 1900s, the Imperial Navy could not match the quantity of British ships arrayed against it.3 Thus the admirals of the Hochseeflotte settled on a policy of attriting British vessels by attempting to isolate portions of the Royal Navy, defeat them in detail, and prepare the way for a final confrontation on even terms somewhere in the North Sea. That policy failed, in part because British Intelligence monitored German wireless traffic and knew exactly when the Hochseeflotte sailed. German planning and British Intelligence efforts set the stage for the battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916.

Hitler would have died with Luck aboard the Wiesbaden at Jutland, had not a curious event occurred in late March 1916. While enjoying a weekend pass, Hitler chanced to be reading a recent translation of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History while sitting in a small cafe near the naval base at Kiel. He acquiesced to the request of a well dressed civilian to join him at his table, leading to a long discussion of the book in general and the importance of achieving a crushing, Trafalgar-esque victory in particular. Impressed by the young petty officer’s knowledge and zeal, the ‘civilian’ eventually revealed himself to be none other than Erich Raeder, chief of staff to Vice-Admiral Franz von Hipper, commander of the Imperial Navy’s battlecruiser squadron. When asked if Hitler would value a place on Raeder’s own staff, the overwhelmed sailor could only nod an affirmative. Four days later (and suffering from a tremendous hangover, courtesy of a farewell party staged by Luck and the crew of the Wiesbaden) Hitler transferred to the battlecruiser Lützow, Hipper’s flagship, as Raeder’s personal yeoman. Over the following weeks, Hitler continued to impress Hipper’s chief of staff with his theoretical knowledge of sea power and his fine memory for detail.4

Jutland not only brought the direct association of Raeder and his yeoman to an end, it almost spelled the end of Hitler, himself. In the thick of the action, ten British heavy calibre shells and a torpedo eventually crippled the Lützow. Even as Hipper and Raeder prepared to transfer to another battlecruiser, an internal explosion laced the deck of the doomed flagship with shrapnel. Caught in the explosion, bleeding and concussed, it would be five days before Hitler, who had volunteered to lead a damage control party, regained consciousness.

Twice during Hitler’s three-month convalescence, Raeder personally visited his favourite yeoman. Though newspapers declared Jutland a tactical victory for the Hochseeflotte based on tonnage lost, both men realised that the British blockade could never be broken by the weaker German fleet. This became clear during the first, and unofficial, visit. As Hitler later recorded in his autobiography, Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’), discussion turned to the future of the German Navy. Both men agreed that Great Britain would remain the greatest threat to Germany in this and any future war. Indeed, Hitler, upon learning of the loss of the Wiesbaden and its entire crew - his dear comrades! – at Jutland, took the first steps toward developing a near pathological hatred of all things British. Raeder, steeped in conservative naval tradition, still favoured the search for a single climactic battle to destroy the Royal Navy. Hitler openly agreed with the officer, but privately saw this approach as hopeless, and wondered if another means of destroying the Royal Navy was not already at hand - the Unterseebooten (or U-boats, Germany’s submarines).5

At the end of Raeder’s second visit, an official visit to award the petty officer the Iron Cross First Class in recognition of his valour at Jutland, the chief of staff offered to assist Hitler in any way possible. Hitler immediately requested a transfer to U-boats. Though shocked, Raeder recognised the young man’s desire to strike at the hated British, something no longer possible in the Hochseeflotte. He not only approved the transfer, but also pulled the necessary strings to promote Hitler to probationary Leutnant-zur-See. This made Hitler somewhat of an oddity: a Volksoffizier, a commissioned officer raised from the ranks in an overwhelmingly aristocratic officer corps. But, as Raeder undoubtedly surmised, such would matter little in the tight confines of the submarine service.6

Thus, in late September 1916, Hitler reported aboard U-39. He thrived; in fact the only criticism recorded in his fitness reports concerned the intensity of his hatred for the British foes, a hatred that his captain feared could lead to excessive risk-taking in Hitler’s zeal to sink British vessels. On the other hand, the lieutenant received the highest praise for the quickness with which he learned the complicated operation of the boat and grasped the tactics of both gun and torpedo, as well as for his leadership skills. Even the captain seemed somewhat mesmerised by the sheer intensity of the Austrian.

By January 1917, Hitler was serving as (still probationary) second watch officer of U-39. In that month, a new watch officer joined the boat. As with Hitler, Karl Dönitz had begun his naval career in cruisers, then transferred to submarines. The two men became fast friends; in fact, Dönitz would later credit Hitler as his role model for the boldness and inspirational leadership that characterised his career. During long watches and shared miseries, the officers often discussed the future of naval warfare. Decades later, Dönitz would recall one miserable watch in particular. With the ship running on the surface at night and both men soaked to the skin, he envisioned fleets of submarines, each boat of tremendous size, range, and destructive power, that could, perhaps, circle the globe without once rising to the surface to replenish air, charge batteries, and soak watch officers. Hitler shrugged, then pointed to the waves that often towered above the fragile vessel. What point in such fleets, he questioned, if they could not even find the enemy? What good would they serve if they could project their firepower only over short distances? First, asserted Hitler, some method of discovering the enemy at a distance was needed; then, some method of killing that enemy at a distance had to be found; then, perhaps, whining third officers could stay dry. Dönitz recalled that he laughed, and asked if adding seaplane hangars to his new submarines would satisfy his friend. Perhaps, the second officer replied, or perhaps something more would be needed.7

By 1917, German unlimited submarine warfare offered the only real chance of convincing Great Britain to leave the war and to end its blockade. Instead, a starving Germany watched as a new enemy, the United States, entered the alliance against it. Fortunately, the collapse of Russia allowed the transfer of forces to the West, and a renewed offensive in France held hope that the war could be ended favourably before American troops arrived in quantity. As for the navy, the Hochseeflotte remained useless except as a fleet-in-being, and the U-boat force shouldered an increasingly heavy load. In March 1918, Hitler received a promotion to Kapitänleutnant (Lieutenant-Commander) and a transfer to U-71 as the executive officer of Korvettenkapitän (Commander) Kurt Slevogt. His friend, Dönitz, had been transferred to the Mediterranean, where he soon commanded a submarine of his own.

When U-71 unmoored at Kiel in October for a new patrol, few of its crew harboured doubts that the end of the war was close. Some sailors, in fact, might well have refused to sail if not for the silver tongue of their charismatic executive officer. Hitler, having just learned that Dönitz’s boat had been lost in action, called for one last strike against the English, one last blow for German honour, one last pound of British flesh to avenge dead comrades. To the last man, the crew cheered and vowed to follow their officers to Valhalla – or to Hell.8 On 1 November their chance to see one or the other of those locations appeared near. Driven deep by British escorts after torpedoing two merchant ships in a daring daylight surface attack, depth-charges pounded U-71. Suddenly, a series of loud noises shook the boat, almost as if a hammer were repeatedly striking inside the vessel. Rushing from the control room to the engine room, Hitler saw that one of the quarter-ton pistons had been ripped from the engine by concussion and was banging at the thin inner wall of the boat. Knowing that if the noise did not pinpoint the submarine’s location for its attackers, then the piston would soon punch through the hull and sink the vessel, he leapt to cushion the blows with his own body.

U-71 survived, and the engine was even repaired later that night. As the boat crept home, Adolf Hitler lay near death, his skull fractured in his act of heroism. Admitted to Kiel Naval Hospital on 10 November, Hitler finally regained consciousness on 15 November. The following day the doctors gave him two pieces of news that would change his life forever. First, the young officer could never again go to sea. Irreparable damage to his inner ear would impact his sense of balance for the remainder of his life, guaranteeing symptoms similar to seasickness if he even tried to stand on a rolling deck again. Second, an armistice had been signed, and though negotiations continued, Germany had lost the war.

Broken in body an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- ALTERNATE HISTORY FROM FRONTLINE BOOKS

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- MAPS

- The Contributors

- Introduction

- 1. The Little Admiral, 1939: Hitler and the German Navy - Wade G. Dudley

- 2. Disaster at Dunkirk: The Defeat of Britain, 1940 - Stephen Badsey

- 3. The Battle of Britain, 1940: Triumph of the Luftwaffe - Charles Messenger

- 4. The Storm and the Whirlwind: Zhukov Strikes First - Gilberto Villahermosa

- 5. The Hinge: Alamein to Basra, 1942 - Paddy Griffith

- 6. Into the Caucasus: The Turkish Attack on Russia, 1942 - John H. Gill

- 7. Known Enemies and Forced Allies: The Battles of Sicily and Kursk, 1943 - John D. Burtt

- 8. Luftwaffe Triumphant: The Defeat of the Bomber Offensive, 1944-45 - David C. Isby

- 9. Hitler’s Bomb: Target: London and Moscow - Forrest R. Lindsey

- 10. Rommel versus Zhukov: Decision in the East, 1944-45 - Peter G. Tsouras

- Plate section