- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The landscape and people are the two most distinctive qualities of the Yorkshire Dales, and this book employs new sources and methods to help the reader see both in a different light. In earlier centuries, religious and social factors influenced the first names that were given to children. Distinctive surnames were inherited, and their expansion or decline can throw light on local communities, on migration and population growth. Place-names emerged from regional and customary practices that illuminate topography, husbandry, mining, communications and much more. Thebook also uses material from Quarter Sessions, title deeds, wills and other documents to investigate a wide range of topics that touch on the lives of individuals and families, from religious dissent to sheep-stealing and vagrancy. There is emphasis too on the poor, showing the impact on families and communities of bastardy, fire, flood, violence and other disasters. A book written for anyone interested in the local and family history of the Yorkshire Dales.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Yorkshire Dales by George Redmonds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Landscape and Place-Names

The emphasis in place-name studies was formerly on the etymology of the most important settlement sites, and scholars used that information to discover more about the local topography and the early history of successive waves of invaders, especially the Anglians, Danes and Norwegians. And yet those names are far outnumbered by the names which were coined in the Middle English period, as the native language was modified by the French of the invading Normans and local dialects developed. More importantly there is often evidence from that period which relates to the circumstances in which the names were coined, and that allows us to define the place-name elements in their local context.

Most place-name elements feature in the standard works of reference but the entries can rarely take account of all the regional distinctions, so it is a field of research open to the discerning local historian. Numerous elements still await the special attention they deserve so a few will be examined here in detail, in order to demonstrate the possibilities of this approach to local studies. These terms once had precise meanings which can reveal much about the history of the landscape and illuminate important aspects of husbandry, stock farming, quarrying, wood management, communications and industry.

BALE HILLS

The minor place-name Bole Hill is very common in Derbyshire, wherever lead was once mined, and it serves to remind us of the places where the ore was burnt or smelted, long before smelt mills came into use. The ‘bole’ was a kind of open furnace, located on a ridge so as to take advantage of the prevailing wind. This is almost certainly how the ore was processed in the earliest phase of the Derbyshire industry and there are place-names and documents that take its history back to the twelfth century. On the other hand there are just two references to the word in the OED, and the first of these, dated 1670, tells us that this was how miners ‘did fine their lead . . . in ancient time’. David Hey has suggested that bole hills were no longer in use by 1580 and he is doubtless right but the practice may still have been fresh in the memory of men in the south Pennines. In 1587, for example, in a dispute that related to ‘a place called Boalehill’, a witness testified that the Earl of Shrewsbury ‘had boals of lead’ on the site and that ‘he himself did burne dyvers boles of lead’ there. The minor name survives in south Yorkshire as Bole Hill (Ecclesall), incorrectly explained as ‘a smooth rounded hill’ in Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire (1961) but dealt with more accurately in The Vocabulary of English Place-Names (1997).

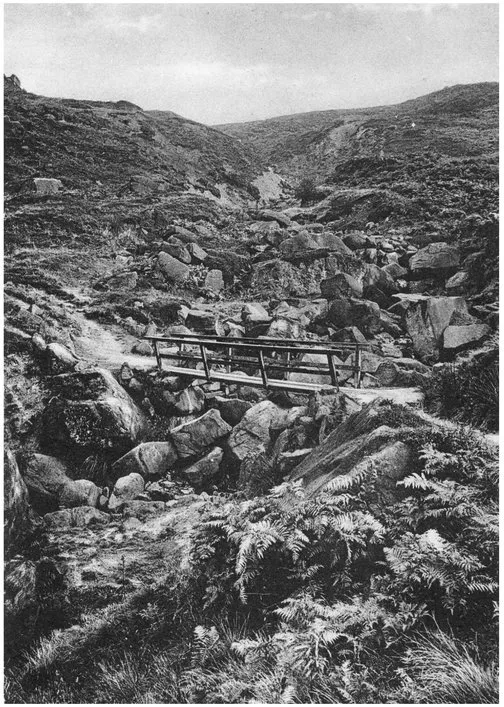

Backstone Beck, Ilkley. Backstones were large, flat mudstones on which oatcakes were baked. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has references to the word from 1531 but minor place-names take its history back to the twelfth century. The inference is that the stones were typically quarried in gills. (Author’s collection)

The late Mary Higham wrote a number of short articles on lead mining in Bowland and noted the use there of the same word. She quoted from the accounts of Henry de Lacy which included the expenses incurred in 1304–5 by mining operations at Ashnott. Two of the items that she listed related to the carriage of the ore to ‘le boole’ where it was burnt, and this use of the English word in a Latin text may indicate that the scribe had difficulty translating it. It appears to be the earliest example on record.

In lead-mining districts further to the north and east, Bale Hill is a place-name with exactly the same meaning and it doubtless represents a regional variation in pronunciation. Much of the evidence is in documents connected with Fountains Abbey, and their Memorandum Book contains an informative sequence of items for the period 1446–58. It describes Robert Merbeke as a ‘baler’ and records payments to him ‘pro labore suo apud lez smeltes’. In an abbey lease of 1527 it was agreed that for every fother of lead they delivered to the monastery the tenants would receive in return ‘at their foreseide bayll hylles eight lodes of ure’. In a Swaledale boundary dispute of c.1560, there was reference to land-holders cutting down wood that would then be burnt ‘at their lead bales’. Several localities named Bale Hill survive in Nidderdale but when the minor names for Swaledale and Wensleydale have been collected others are likely to be found.

Almost incidentally this word suggests that surnames such as Boller, Boler, Boaler and Bowler need to be re-interpreted. The traditional explanation is that they are occupational in origin, for makers or sellers of bowls, but David Hey cast doubt on that when he referred to Ralph le Bolere of Eyam (1300). The Derbyshire poll tax of 1381 has several examples in the lead-mining areas, e.g. Nicholas Boler of Tideswell, and these men or their ancestors seem certain to have been involved in smelting.

CALGARTH

Gardens are mentioned frequently in early title deeds but we know little about them. Stephen Moorhouse wrote an interesting piece on the topic in West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500 (1981), making the point that most food was home grown in medieval society and that vegetables would have been a staple part of the diet in lower-class rural communities. One of the minor names that he discussed was ‘leighton’ or ‘laughton’ which had its origins in two Old English words that meant literally ‘leek enclosure’. The leek, in all its varieties, was no doubt the dominant vegetable in those gardens but the term included other plants in the allium genus such as garlic and onions. The amount of starch in the medieval diet meant that herbs and spices assumed great importance, but ‘leeks’ were thought of as tasty in their own right and that may explain the importance of such specialist enclosures. The inference is that ‘leighton’ eventually developed the more general meaning of vegetable garden but its survival as a place-name is of real interest.

Teresa McLean listed cabbages, peas, beans, lentils, millet and onions as the basic vegetables of medieval England, but the common minor names Beanlands and Pease Close suggest that these vegetables would often have been grown in the fields rather than in plots close to the house. The cabbage, like the leek, appears to have been important enough to merit its own enclosure and it was an equally valuable part of the peasants’ diet. It has given rise to very few place-names but Colworth (Bedfordshire) and Colwich (Staffordshire) derive from an Old English word for cabbage and are evidence of the plant’s early importance.

In the north the generic term for brassica plants was kale and this occurs in the minor place-name Calgarth which means ‘cabbage yard’. The spelling points to Scandinavian influence and references to the term date from the thirteenth century. Kail Hill in Appletreewick is from the same period and since it overlooks Calgarth House in Burnsall it is tempting to link the two place-names. This Calgarth was described as a ‘culture’ or ‘close’ in c.1280 but it was named Calgarthouse in a fine of 1515 which indicates that by then it was a settlement site. One such ‘cabbage yard’ must have given rise to a by-name or surname, since a John Calgarth was named as the former tenant of a house in Markington in 1479.

Later examples of the word are also of interest, since they indicate how long the calgarth retained its importance. There were evidently such gardens well into the sixteenth century, for John Hudson was granted a lease in 1518 of ‘one place in Esholte with the Call-garthe thereto belonginge’. The same property is listed in the Dissolution rental of 1540 as ‘a house called the hole hall and the calle garth’. There are other clues as to how long it survived as a meaningful word: in 1575, for example, a Burton in Bishopdale inventory listed ‘one calgarth spade’ whilst in 1621 Edward Nealson of Abbotside willed that Jane Metcalfe should ‘have houseroome and fire and one calgarth during her naturall life’. A lease of property in Askrigg in 1700 included ‘one callgarth’ and this too seems to have referred to a garden.

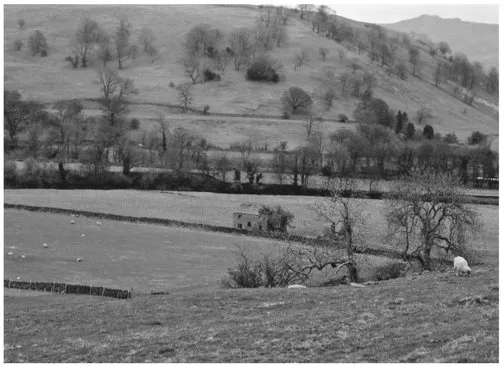

Calgarth: a ‘culture’ that was said to be in Appletreewick in 1303 but in Burnsall before the century was out. The farm sits in an ox-bow and the likelihood is that the Wharfe changed course in that period. Kail Hill is in the background. (The author)

The survival of Calgarth as a place-name makes it difficult to discover just when this specialised garden began to decline in importance, but a sequence of deeds for Horton in Ribblesdale may mark its transition into a place-name. In 1677, Lancelot Smithson conveyed a partitioned dwelling-house in the parish to Miles Taylor which included ‘half the great calgarth or garden’. In 1693 this was described as a moiety of ‘the Great Calgarth or garden on one side of Hebden farm’ and in 1712 as ‘half Hebden Call Garth’. Colegarth is a place-name with exactly the same meaning but with ‘cole’ rather than ‘kale’ as the prefix. This was the usual English spelling and it may sometimes have replaced the regional word. Colgarth Hill in Airton is one example, for it was spelt ‘calgarthes’ in 1603.

COMBS

The Celtic cwm, widely known because of the hymn Cwm Rhondda, was the word for a valley and it passed into the vocabulary of Old English with that meaning. It is listed in glossaries as cumb and we associate that element most strongly with south-west England. Nevertheless, there are similar place-names in several other parts of the country, especially in those areas where Britons and Anglo-Saxons were neighbours over a long period. In Cumberland, for example, it is a relatively frequent prefix, found in Cumcrook, Cumdivock and Cumwhitton, to mention just a few. One of the best-known Westmorland names is Great Coum in the Lake District, interpreted as the ‘great valley’.

There is a group of place-names in the north-west corner of Yorkshire, particularly in areas close to Westmorland, which has received little attention but which may include some with cumb as an element. Among these are Comb (Sedbergh), Comb Gill (Garsdale), Combe (Dent), Comb Stoop (Buckden) and Combe Scar (Ingleton). Combs in Austwick and Comb Scar in Malham are not far away, and further east are Combes Hill (Appletreewick), Combs (Beamsley) and Combs near Ripon. Unfortunately, few early spellings of these names have been recorded.

In Malham, Comb Hill and Scar are said to derive from camb or kambr, the Old English and Old Norse words for a ‘comb’ or ‘crest’, the crest of a ridge that is. This meaning seems to be linked in some way with the cock’s ‘comb’, a sort of modest northern equivalent of ‘sierra’, the Spanish word for a saw. Cam Fell in Horton in Ribblesdale and Cam Gill in Kettlewell seem certain to derive from that word. The interpretation of the Malham place-name is based on the topography and the earliest spelling located, i.e. Cam Scar, found in the 1849 tithe award. It is apt enough but the final interpretation may depend on the location of spellings much earlier than 1849.

Many more of the ‘combs’, notably those in Austwick, Dent and Sedbergh, were said in PNWR to derive from the Middle English word culm, which had meanings such as ‘coal dust’, ‘peat dust’ and ‘soot’. Again, much of the evidence is late but a relatively early spelling for one of the Dent place-names supports that explanation, i.e. ‘Cowlme’(1592). The first spellings for the other localities are: Lowcome in Sedbergh (1656); Coumerigg in Austwick (1676) and Cowme in Dent (1620). I have no doubt that the interpretation in these cases was influenced by spellings such as ‘Cowme’, which hint at a lost ‘l’ and by the fact that some of the names occur in places where there were or had been coal workings and smithies.

‘Cowme’ was certainly used in the north-west as a local word for peat dust, for Angus Winchester quotes a by-law of 1689 for Castlerigg in Cumberland which ordered tenants to clean up the ‘cowme’ when removing peats. The most frequently-quoted use of this word is the one found in George Owen’s description of lime-kilns in Pembrokeshire, in which he referred to ‘a fier of coales or rather culme, which is but the dust of coales’ (1603). A Nottinghamshire document contains the Latin phrase ‘carbonum marinorum et culmorum’ (1348), a reference that takes the word back to the fourteenth century at least.

Nevertheless, the evidence does not always point to ‘culm’ or to ‘comb’. In the Teesdale village of Romaldkirk, for example, there is an early reference to a place-name that was not noted by Professor Smith. It is found in an undated grant of a vaccary and cannot be later than 1261. The grant included the right to enclose and assart land in ‘Cumbis’ or ‘Coumbis’, a name which seems likely to derive from the Celtic cwm. Similarly, Combs in Austwick has now been found on a map of 1619 as Combe Nabbe and here too the spelling may point away from the traditional interpretations. Only the location of earlier evidence will help to determine how many of these Pennine names contain the word for valley that predates ‘gill’ and ‘dale’.

CRUTCHING

In the English Place-Name Society’s ten volumes for Yorkshire there are just half a dozen places which have this element as a prefix and they are all in the Dales. It is a small number but others may turn up as more work is done on field-names. The spellings vary but they are sufficiently alike for us to feel that they share a common origin. Crutching Close features three times, in Langcliffe, Rylstone and Settle and there is Crutchon Close in Halton Gill; Crutchin Gill in Horton in Ribblesdale and Crutchenber Fell in Slaidburn. In each case the evidence is late, post 1840, collected from tithe awards and an Ordnance Survey map. Smith offered no etymology for the word and it was not listed in the section on ‘elements’ in volume VII of PNWR.

In the case of Crutchenber (Fell) it is possible to find much earlier spellings, using the work done on Slaidburn by C.J. Spencer and R.H. Postlethwaite. In the parish registers, for instance, there are half a dozen references between 1703 and 1810 to what was clearly a settlement, possibly a single dwelling. A succession of families had it as their place of residence, starting with Richard Coate ‘de Crutchinbare’ (1703) and ending with William Leach ‘of Crutchinber’ (1810). References from wills take the history back to the early seventeenth century when John Guy ‘of Crutchanbarr’ (1629) and Robert Scotson ‘of Crutchonber in Bolland’ (1615) were the occupiers of the property.

There is a further interesting reference in the Quarter Sessions records for 1719–20. Slaidburn was described there as consisting of three meers, named as Rishton Grange Meer, Hamerton Grange Meer and Essington Meer, all still recognisable territories. It was judged to be their common responsibility to maintain ‘a cawsey which leads over Bolland Knotts’ because it belonged ‘equally amongst them being all within one township’. Soon afterwards they mentioned that ‘a new cawsey over a place called Crutching bar’ was being made. This seems to be a reference to the hill rather than to the settlement but it may indicate how the settlement name originated. In all these spellings the suffix clearly derives from a word for hill, either Old English beorg or Old Norse berg–a very popular element in Ribblesdale.

The solution to the origin of ‘Crutching’ is to be found in the records of Fountains Abbey, specifically in those documents that inform us about livestock and customary practice among the tenants who were responsible for the abbey’s cattle. There were numerous leases from 1512 onwards which had to do with the ‘renewing’ of the herds at twelve-month intervals; that is making arrangements for the older animals to be replaced by younger ones. Typically, ‘nine of the oldest and most crochy cows’ were passed on to the abbey’s chief herdsman early in the year and nine ‘whyes’ or heifers were introduced into the herd later. I have come across no other use of the adjective ‘crochy’, but the noun ‘crochon’ occurs regularly. It referred to the older beasts which were moved to good pasture land at Whitsuntide and fattened there in preparation for their slaughter in the autumn. An entry in the abbey rental of 1495–96, difficult to translate accurately, seems to link such a pasture with ‘lez Crochons’. These early details of a long-forgotten custom demonstrate just how an enclosure or grazing ground might acquire the type of place-name mentioned earlier.

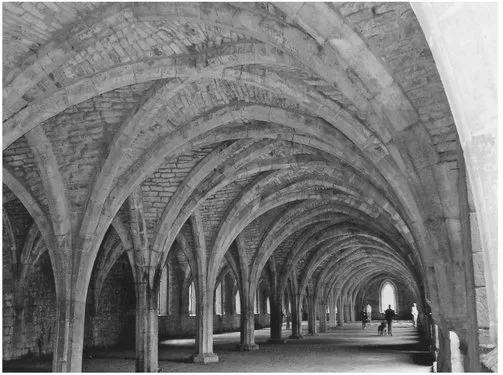

The Cellarium, Fountains Abbey. Eight of the twenty-two bays were used to store provisions and they were formerly separated from the rest of the undercroft by a wall that has now been demolished.

That is not quite the end of the matter, for in a published account book for the abbey, which covered the years from 1446 to 1459, there are several items which seem certain to refer to crochons, where the word has been mistakenly transcribed as ‘crochous’. In more than one case it is found in a list of specialist words for cattle such as drapes (milkless cows) and stirkettes (young bullocks), so it is reasonable to assume that ...

Table of contents

- Also available from Pen & Sword Books Ltd:

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - Landscape and Place-Names

- Chapter 2 - Places and People

- Chapter 3 - Place-Names and Surnames

- Chapter 4 - Surname Histories

- Chapter 5 - First Names in the Dales

- Chapter 6 - Migration

- Chapter 7 - The Quarter Sessions and Dales Life

- Chapter 8 - Bridges and Highways

- Sources

- Index