![]()

Merchantmen

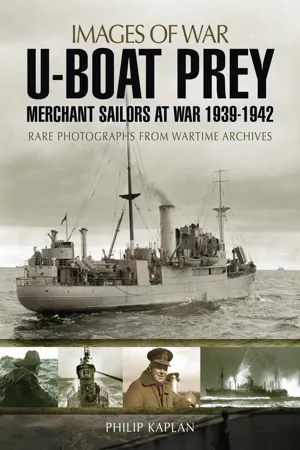

The badge of the Merchant Navy

For the bread that you eat and the biscuits you nibble, the sweets that you suck and the joints that you carve, they are brought to you daily by all us Big Steamers—and if any one hinders our coming—you’ll starve.

—from Big Steamer by Rudyard Kipling

God and our sailors we adore, when danger threatens, not before. With danger past, both are requited, God forgotten, the sailor slighted.

—anon, circa 1790

After every war, monuments are raised to the memory of those who died gloriously. The officers and men of the Merchant Navy, fighting this grim Battle of the Atlantic, would probably scorn such homage to their simple devotion; but it is a regrettable fact that the one memorial they would care for—the refutation of the charge explicit in the above quotation—is still, after two hundred years, unforthcoming and the slur unexpunged from the annals. For two hundred years and more, these brave men, lacking the training and organisation that adapts their brothers in the Royal Navy so readily to the rigours of war, have, nevertheless, fashioned their own magnificent tradition. Day in, day out, night in, night out, they face today unflinchingly the dangers of the deep, and those that lurk in the deep—the prowling U-boats. They know, these men, that the Battle of the Atlantic means wind and weather, cold and strain and fatigue, all in the face of enemy craft above and below, awaiting the specific moment to send them to death. They have not even the mental relief of hoping for an enemy humane enough to rescue; nor the certainty of finding safe and sound those people and those things they love when they return to homes, which may have been bombed in their absence. When the Battle of the Atlantic is won, as won it will be, it will be these men and those who have escorted them we shall have to thank. Ceaseless vigilance and the will to triumph over well nigh insuperable obstacles will have won their reward.

—Admiral Sir Percy Noble, Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches

14th August 1941

When Admiral Horatio Nelson defeated Napoleon’s Franco-Spanish fleet off Cape Trafalgar on 21st October 1805, only to die in his hour of triumph, the population of the British Islands, mourning the hero while rejoicing in the victory, numbered approximately sixteen million. They were a proud and almost self-sufficient people, needing little more than such luxuries as silks, tobacco, tea and coffee to satisfy their wants from overseas. Nearly one-hundred and thirty-four years later, when World War Two began, there were more than fifty million mouths to feed, and Britain had become increasingly reliant on a constant flow of imports, not only to maintain her position as a major manufacturing nation, but merely to survive.

Whether it was ever pedantically correct to give the title “Merchant Navy” to Britain’s trading fleet can probably be questioned. There had been a time when the same ships were used for fighting and for trading, but those days had passed with the cannon and the cutlass. The fighting ships, their officers and men, remained in the service of the Crown, ever ready to wage the nation’s wars, while the rest sailed the oceans of the world with one main objective—to enrich the ship-owners. And the owners were a very diverse group, with their offices in all the major ports, with a wide variety of vessels, embracing Saucy Sue of Yarmouth and the Queen Elizabeth, with motives ranging from the frankly mercenary to the idealistic, and with their employees’ wages varying between the handsome and the barest subsistence levels.

So the Red Ensign flew above a multitude of ships, belonging to a multitude of individuals, each with different notions of how to run a shipping business. Nevertheless, it was due to their industry, by whatever means and for whatever motives, that by the 1930s the British Empire and the Commonwealth had developed into the greatest trading community the world had ever seen, with global port facilities and a merchant fleet of approximately 6,700 vessels—more than double the number of their nearest rival, the United States of America. It was said that, on any one day in the year, 2,500 vessels registered in Britain, were at sea or working in a port, somewhere in the world. But Britain’s dependence on the imports carried by those ships was her greatest weakness in wartime, when her long-established freedom of the sea was challenged by a foreign power. That weakness had been ominously demonstrated during World War One when the U-boats of the Kaiser’s navy had targeted Britain’s cargo ships, and there had been times in 1917 when starvation had stared her people in the face.

With that vulnerability in mind, the government requisitioned all shipping at the start of World War Two. In service, the ships remained under the management of the line owners, who acted as agents for the Ministry of Supply, and later for the Ministry of War Transport, which, on 1st May 1941, was formed from the Ministries of Transport and of Shipping. Experts from the shipping lines, with civil servants from the Ministries, formed a central planning group which, for the duration of the war, was to decide where the ships would sail and what cargoes they would carry. The owners remained responsible for maintaining and provisioning their ships, while the newly-formed Merchant Navy Pool assumed the task of crewing.

A merchant sailor climbing to his job at sea.

Part of an Allied convoy bringing vitally-needed goods from North America to Britain in the Second World War.

From 1939 to 1945, the names of ships built in British shipyards for the Government, old World War One vessels purchased from the United States, or captured tonnage, took the prefix “Empire”, Empire Byron, for example, Empire Chaucer and Empire Starlight, while those built in Canada were “Fort” or “Park” (suffix) (Fort Brunswick, Avondale Park). The Canadian-built ships were owned by the Canadian government and manned by Canadian seafarers. Some did come under the British flag and were renamed with a “Fort” prefix. American-built ships were “Ocean”, as in Ocean Vengeance, or, if they were to be manned by British crews, “Sam” boats, as in Sampep and Sambolt, and were emergency-built Liberty ships that were bare-boat chartered to the British government and renamed. The “Sam” was popularly taken to be a reference to “Uncle Sam”, but the official interpretation was that it described the profile of the ship—“Superstructure aft of midships”.

At any period of time in World War Two, there might have been a dozen convoys on the wide Atlantic, each numbering anything between ten and over a hundred ships, some bound for Britain with their vital cargoes, others sailing outbound in ballast to collect the next consignment. The commercial fleets were composed of many varieties of ship—fast and slow, large and small, old and new, coal-fired and oil-fired—and the ships were crewed by men of widely different nationalities and faiths, some of whom felt loyalties which lay more with their calling and their shipmates than with their owners or the British Crown.

A merchant sailor on convoy duty,

above and below: Convoy conferences were held at Admiralty House in Halifax, Nova Scotia and were normally attended by the captain and the wireless operator of each ship to sail in a convoy.

The merchant ship captains, or masters, were accustomed to taking orders only from their owners, and not from officers of the Royal Navy, nor of the Reserve, no matter how much gold braid they might wear on their sleeves. In the first few months of war, few were in favour of the convoy system, and preferred to make their way alone. In this they were at one with their owners, who regarded the days spent in assembling the vital convoys and attending Commodore’s conferences as so much unproductive time. The masters, for their part, did not care for the discipline required. They mistrusted (and not without reason) the rendezvous in mid-Atlantic when they were supposed to exchange escorts with a convoy coming west, and they feared the dangers of collision in the fogs that were common, at all times of the year, off the coast of Nova Scotia. It was only later, when the U-boat wolfpacks began to make their deadly presence felt, that most owners and masters accepted the fact they had to have protection, and that ships sailing alone could not be protected. Although they were as diverse in their ways and opinions as any other group of men in skilled occupations, the masters had it in common that, like their crewmen, they took pride in their calling; they also tended to believe in a destiny that shaped all human ends, and to accept whatever blows of fate, and particularly of nature, that might come along.

Until June 1940, many merchant ships were employed in the transport of the British Expeditionary Force, to the western coast of France, and in maintaining its supplies. It is remarkable that, in the nine months of the operation, only one ship was lost, and that was due to misadventure, not to action by the enemy.

Then, in May 1940, came the Blitzkrieg—the lightning strike by the Wehrmacht, spearheaded by the Luftwaffe, on Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and France. Soon, every ship that could be mustered was needed to evacuate the bulk of the BEF, along with many French soldiers, from the beaches of Dunkirk, and to bring detachments home from Calais, Brest, St Nazaire, Le Havre and Boulogne. On 17th June, the Cunarder Lancastria, which a week earlier had taken part in the withdrawal from Norway, was ready to sail from St Nazaire with approximately 5,300 servicemen aboard, including a large RAF contingent, when she was hit by bombs from a Dornier Do-17, and went down. There were only enough lifeboats and rafts for a fraction of the complement, and despite all rescue efforts by the destroyer HMS Highlander, HM trawler Cambridgeshire, and other ships, during the continued air attack, 2,833 of Lancastria’s crew and passengers were lost.

The day following the Lancastria disaster, the Blue Star liner Arandora Star, which had also been involved in the Norway operation, and had been plying to-and-fro between France and England with a weary crew ever since, sailed from Liverpool for St John’s, Newfoundland, carrying 1,213 German and Italian internees, eighty-six German POWs, a military guard 200-strong, and a crew of 174. She was sailing on a zig-zag course, as was customary when a ship was not escorted, off the northwest coast of Ireland shortly before dawn on 2nd July when she was hit by a torpedo launched from Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien’s U47. The Arandora Star went down with 750 of her passengers, her Captain, twelve officers and forty-two members of her crew.

The so-called “phoney war”, which, for the men of the Royal and Merchant Navies, had never been anything but in deadly earnest, was over, and now its reality was clear to all the world. Materially and physically supported by her Commonwealth and Empire, and morally at least by the majority of Americans, Britain was left to carry on the fight against a rampant Germany, now joined by an opportunist Italy, and with access to captured bases stretching from Norway to the Spanish border. In July 1940, two outward-bound convoys, CW7 and CW8, were attacked in the English Channel by E-boats (German motor torpedo-boats) and bombers. In that month, forty Allied cargo ships were sunk by air attack alone. The ports of Dover, Weymouth, Portland, Plymouth and Cardiff were all heavily bombed, and inbound vessels had to be re-routed to the Bristol Channel, the Mersey and the Clyde. Nor were they immune there from the Luftwaffe’s attentions.

Wrens working in the Operations Plotting Room at Naval Services Headquarters, Ottowa, December 1943.

Admiral Sir Max Horton was a British submariner in World War One and Commander-in-Chief of the Western Approaches during the latter part of World War Two.

It was decided that the headquarters of the C-in-C Western Appraches Command, from which the ship...