- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The U-Boat War in the Atlantic, 1944–1945

About this book

This is the second of three volumes covering the U-boat campaign in the Atlantic during the Second World War.This is the fascinating account, as told from the German perspective, of the Battle of the Atlantic, the longest-running, continuous military campaign in World War II, spanning from 1939 through to Germany's defeat in 1945. At its core was the Allied naval blockade of Germany, which was announced the day after the declaration of war, although it quickly grew to include Germany's counter-blockade. The name "Battle of the Atlantic", was coined by Winston Churchill in 1941 and he famously stated that the U-boats were the only thing that really frightened him. The U-boat war encompassed a campaign that began on the first day of the European war and lasted for six years, involved thousands of ships and stretched over thousands of square miles of ocean, in more than 100 convoy battles and perhaps 1,000 single-ship encounters. In the 68 months of World War II, 2,775 Allied merchant ships were sunk for the loss of 781 U-boats.This is the story of that massive encounter from the German perspective. Published in three volumes, this work was compiled under the supervision of the U.S Navy Department and the British Admiralty by Fregattenkapitan Gunther Hessler. The author, though without previous experience as a writer, had first hand experience of U-boat warfare having commanded a U-boat in 1940 and 1941. For the remainder of the war he was Staff Officer to the Flag Officer commanding U-boats. He had access to German war diaries and other relevant documents concerning U-boat command, and this work based on these many documents, tells the story entirely from the viewpoint of that command. For this reason this work is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of World War II from primary sources and will be of enduring interest to those engaged in attempting to unravel the true nature of submarine warfare in World War II.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The U-Boat War in the Atlantic, 1944–1945 by Bob Carruthers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

- CHAPTER 8 -

NORTH ATLANTIC SEPTEMBER 1943 - FEBRUARY 1944

SEPTEMBER 1943

ESTIMATION OF THE EFFECT OF ZAUNKÖNIG

ESTIMATION OF THE EFFECT OF ZAUNKÖNIG

372. New weapons and equipment ready to time

Increasingly heavy U-boat losses in the Bay of Biscay and in remote areas from July onwards spurred us to redouble our efforts in order speedily to end the untenable situation in the Atlantic. Special measures had been needed to keep the production of new weapons and equipment up to schedule, in which respect the T5 torpedo (Zaunkönig) caused the greatest difficulty. In the normal course of production this weapon would not have been ready for use until the beginning of 1944, which would have upset all our plans, and Dönitz therefore entreated the Armaments Minister to hasten production. The Navy was thereupon allocated additional production capacity, with a number of highly qualified technicians assigned for the manufacture of the complicated components of the acoustic apparatus, and by dint of further stringent measures and at the expense of other armaments commitments, 80 T5 torpedoes were delivered to the western bases, as originally intended, on 1st August 1943.

The T5 torpedo had not yet been tried out in the Atlantic, so that it was not improbable that, at first, serious failures would occur and that the U-boats would receive considerable punishment at the hands of enemy destroyers; but, in the interest of the earliest possible resumption of operations against convoys, Dönitz decided to accept the risk provided that the torpedoes arrived on board the U-boats in perfect condition. However, the least shock during transport from factory to base could throw the highly complicated and sensitive homing device of the T5 out of adjustment. The torpedoes had, therefore, again to be carefully tested and adjusted before being supplied to the boats. This work could only be done by specially trained precision-mechanics and required special testing apparatus, which was not at first procurable. Once again through Speer’s intervention, personnel and equipment were made available, and at the beginning of August the first T5 maintenance units were established in the western bases. Units were also established in the Mediterranean, at Kiel and in the Norwegian bases on 21st September, 3rd October and the end of 1944 respectively.

373. Preparations for the resumption of convoy operations

The U-boat crews had not remained in ignorance of our heavy losses in the Atlantic and it had needed the personal influence of Dönitz and the Senior Officers of flotillas to maintain their fighting spirit. Since July 1943, Dönitz had repeatedly pointed out that the introduction of the new weapons would soon change the Atlantic situation in favour of the U-boats and the Metox denouement also served to restore the confidence of the U-boat commanders for their impending battles.

“… 23rd August 1943. Recent months have brought severe reverses for the U-boat campaign. Inexplicable losses have occurred among boats in transit and in waiting areas. Our U-boat dispositions have been circumvented by the enemy and our successes have declined. This we attributed to enemy location gear of a new, undetectable type. It has now been established by experiment and confirmed by the statements of prisoners of war, that it was due to the enemy’s interception of strong radiation from the Metox radar search receiver. This instrument is now being superseded by the nonradiating Hagenuk, with which it is possible to detect intermittent radar emissions on all the principal frequencies. The radar question thereby undergoes a decisive change.

At the same time the boats are being supplied with new torpedoes and a heavier AA armament, thus providing the prerequisites for a resumption of the battle, under new conditions, with all its old daring and determination.

This message is to be promulgated forthwith to all commanding officers, but in no circumstances are details of the new torpedoes and the Metox revelations to be imparted to the crews…” (354).

Four months having elapsed since the last convoy battle, it was essential, for psychological reasons, that the next one should prove successful. Since success could only be expected if the crews were familiar with the new weapons and the commanders thoroughly conversant with the combined-attack tactics, officers and men underwent special training courses in July and August. The Commanding Officers were instructed at U-boat headquarters, where they were familiarised with the operational possibilities presented by the new weapons (355).

The U-boats’ objective was to remain the same, namely to attack enemy merchant ships, while the new weapons were only to be used to force a breach in the enemy air and surface escorts should the boats fail to approach the convoy unobserved. Opportunities for attack would be greatest if the enemy were taken by surprise, so it was essential that the boats should remain unobserved when taking up formation, when seeking to gain bearing on a convoy and also in the first stage of the attack. Lookouts and Wanze had therefore to be employed to the best effect, but, in case U-boat commanders should be over-influenced by Wanze warnings, it was necessary to remind them that this instrument was only intended as a safeguard against surprise attack and that they should not submerge unless the enemy was actually in sight. In the second stage of the attack, namely before the arrival of the enemy support groups, there was still no need for the boats to expose themselves; only in the last and most difficult stage was this necessary, if, because of heavy opposition from air and sea, they were unable to reach an attacking position unobserved.

In giving battle to the enemy air escorts, all boats in the vicinity of the convoy were, as far as possible, to engage simultaneously. In contrast to former practice, the boats had now to synchronise their tactics, but unfortunately they had no R/T equipment to facilitate this. The fitting of such equipment would have been a lengthy process, quite apart from which the boats were already crammed with radio sets, radar search receivers and other gear of every conceivable kind. It was therefore laid down that the signal “Remain surfaced to engage aircraft” should be obeyed by all boats and that they should then refrain from submerging in the event of air attack.

It was important that the boats should, as far as possible, assemble evenly round the convoy, preferably in groups of two, and larger groups were to be avoided.

“… Should a large bunch of U-boats be located by several escort vessels, all would be forced temporarily to withdraw from the battle. On the other hand, the location of, say, six well separated boats, or of several groups of two or three, would draw at least six escort vessels from the convoy and thereby attenuate the convoy escort… Two boats in company are better able to protect themselves against air attack, besides providing mutual support in engagements with destroyers…” (356).

The requisite concentration of U-boats ahead of the convoy was to be achieved during daylight, the boats using their T5 torpedoes against pursuing escort vessels, with the object of reducing their numbers, and engaging the enemy air escorts on the surface. The actual attack was to take place at night, when the boats would thrust their way to the ships of the convoy with their T5 torpedoes. Every opportunity for firing torpedoes had instantly to be seized, both when attacking and when being pursued, and hence the few T5 torpedoes initially available were carried two forward and two aft. For attacks on merchant ships, four G7a Fat and four G7e torpedoes21 (two Fat and two fitted with non-contact pistols) were carried.

“… The convoy battle will demand more from officers and men in the way of alacrity, courage and tactical knowledge and ability than formerly. But the war situation and dire necessity will inspire everyone to do his utmost…”

374. Wanze affords greater security in the Bay

The first large boats equipped with Wanze and heavier AA weapons sailed from Lorient in mid-August. A few days later the medium boats, each with four T5 torpedoes, sailed for their first convoy operation. Anxiously we followed their progress through the Bay of Biscay, though we observed a definite improvement in conditions in that area, for, despite intensive enemy air activity, there were very few reports of attacks on U-boats, either from the boats themselves or from Radio Intelligence. The danger from the enemy blockade had also lessened, for, following a successful Focke-Wulf attack on British hunter groups on 27th August, in which remote-controlled glider-bombs were used for the first time and HMS Egret had been sunk and a cruiser severely damaged, the enemy naval forces had shown a preference for operations further to the westward. The route close to the Spanish coast continued to be reserved for returning boats without radar search receivers, so that outgoing boats had to traverse the dangerous area north of Cape Ortegal. Nevertheless our losses, subsequent to 20th August, remained at a reasonable level, and it can be appreciated that we attributed these changed circumstances to the introduction of Wanze. In a message to the U-boats on 13th September 1943, Dönitz said: “Experience in the Bay of Biscay has shown that the radar situation has changed in your favour”, an opinion he was later to revise. However, conditions in the Bay did, indeed, continue to improve, for our monthly losses up to May 1944 amounted to only one or two boats, compared to 15 in July 1943 alone.

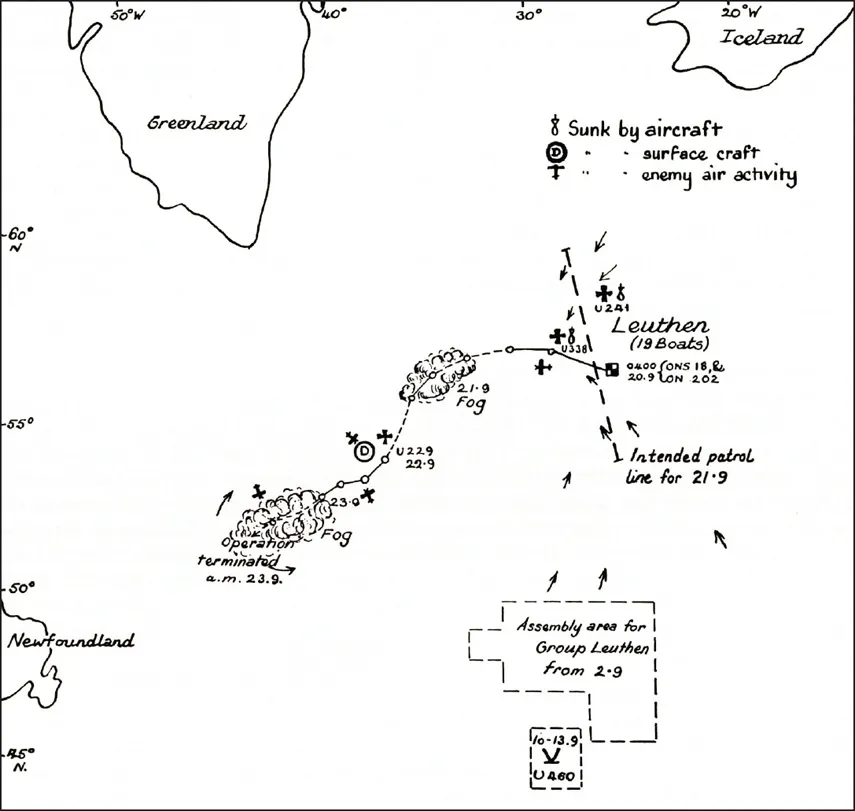

In conformity with the established practice of commencing operations on the eastern side of the Atlantic, an ONS convoy was selected as the first target in the renewed attack. We had no knowledge of its route, but it was assumed that, like most of the convoys which had crossed the Atlantic since the cessation of U-boat attacks, it was taking the shortest one, and a decision was therefore made to dispose the boats in line across the great circle in about 25 degrees West, a position which would be reached by the convoy in the afternoon of 21st September. As an additional precaution against treachery, all positions were radioed in the form of reference points which were only known to the commanders concerned. Five boats replenished from U.460 and on 15th September 22 boats, comprising group Leuthen, were ordered to take up position by the 20th, unobserved.

Plan 63. Group Leuthen, 20th-23rd September 1943. Zaunkönig operation against ON 202 and ONS 18

375. First use of Zaunkönig. Attack on ON 202 and ONS 18

Some of the U-boat commanders were evidently disregarding the order to proceed to their positions submerged, for on the morning of 19th September a British aircraft reported from a little eastward of the intended patrol line Leuthen that she had attacked a westbound U-boat22 and obtained four possible hits. During the afternoon some indecipherable radio messages came in, which we presumed to have been made by the U-boat attacked. This signal activity was undesirable, since it was bound to betray the presence of the boats.

At 0400 on 20th September, before the line was formed, the convoy was sighted sooner than expected on its anticipated great-circle route. By dawn four boats had reached the vicinity in good conditions of sea and visibility, but only one managed to make a submerged attack during daylight, in which she torpedoed two ships. Contact was then lost because of air activity and the appearance of a surprisingly powerful surface escort. At 1730, U.338 made the prearranged signal: “Remain surfaced to repel aircraft”. However, there were insufficient boats in the neighbourhood of the convoy to achieve the desired dispersion of the air cover and U.338 was presumably bombed and sunk shortly after making the signal.

It so happened that ON 202 and ONS 18 had joined company during the day, but as the boats had lost touch we remained in ignorance of this. Contact was regained at dusk, when, despite good visibility only five boats sighted the convoy itself, the remainder being preoccupied with a large number of escort vessels stationed some distance away on the beam and astern. In these engagements the boats carried out no less than fifteen attacks with Zaunkönig and reported seven destroyers certainly and three probably sunk. The ships of the convoy were not attacked, because the number of boats which managed to approach it was insufficient to force the inner screen. They merely sank a badly damaged ship which had probably been torpedoed that morning.

We believed that, by sinking so many escort vessels, favourable conditions had been created for a concerted attack on the convoy the next night. But just then the weather came to the enemy’s help, fog descending early on the 21st and persisting throughout the day and following night, and though remote touch could be maintained by hydrophone and FuMB23 there were no opportunities for attack, for without radar the boats were blind and could not risk an encounter with the escorts. During the 22nd the fog became patchy and enemy aircraft resumed their activity in the afternoon. Nevertheless, the boats fought them on the surface - their AA fire preventing accurate bombing - and managed to gain bearing in face of these attacks, suffering serious damage to only one of their number in the process.

Just before nightfall, when the fog cleared, five boats were in the vicinity of the convoy and went into the attack, but, coming up against a close screen of remarkable strength considering the large number of escort vessels reported sunk earlier on, they achieved only limited success. Nevertheless, we regarded the reported result - five ships of the convoy and five escort vessels torpedoed - as most gratifying. Visibility deteriorated again in the early hours of the 23rd and, with the convoy close to the edge of the fog area north-east of the Newfoundland Bank and with U-boat crews exhausted after their ninety-hour battle in the fog, the operation was broken off. The convoy was last sighted at noon, but there was no attack.

376. Apparent success of the new weapons

From the boats’ radio messages, the result of this four-day battle appeared to be twelve destroyers definitely and three probably sunk by T5 torpedoes, and nine merchant ships sunk by ordinary torpedoes, for the loss of two U-boats.24 This was undoubtedly a splendid achievement and even better results might have been attained had not fog impeded the second day of the operation. But the real criterion for the success of the whole operation was that, according to their reports, the boats had maintained contact with, and gained bearing on, the convoy in face of an air escort comprising both land-based and carrier-borne aircraft, which encouraged us to assume that the new AA armament had had a satisfactorily deterrent effect. As a result of this apparent success it was decided to employ the same tactics in future convoy op...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 7: May - August 1943

- Chapter 8: North Atlantic September 1943 - February 1944

- Chapter 9: May - August 1943

- Chapter 10: June - September 1944

- Chapter 11: October 1944 - May 1945

- Appendices