![]()

THE LUFTWAFFE: EAGLES ASCENDING 1939-1942

The creation of the Luftwaffe which, like the Greek goddess Athena from the forehead of Zeus, sprang fully armed into view in 1936, had been part of Hitler’s policy of re arming Germany in secret. One of the many punitive provisions of the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, which ended the First World War, had been a ban on a German air force as well as substantial reductions in the size of the German army and navy. Clandestine rearmament took place nevertheless, and Hitler announced it to a shocked world in 1935.

Karl Born remembers how the existence of the new air force was revealed.

‘There was an air show in London, and Hitler disguised his men, the NS flying corps, so that they could take part. He wanted to see if the English would object, but when they made no objections, then they were told ‘This is the German Luftwaffe!’

The build up of the Luftwaffe had been concealed behind an apparently innocent interest in gliding and flying clubs. The manufacture of warplanes had been masked by Lufthansa, the German civil airline, which flew passengers in Junkers, Fokker, Messerschmitt and other aircraft that were designed for easy conversion to military use.

The Hitler Youth, the Hitlerjugend, had been at the core of the policy of rearming Germany while at the same deceiving her erstwhile enemies. Outwardly, the Hitler Youth catered for boyish enthusiasms and a sense of adventure. What was really happening was the creation of the most highly trained, highly motivated and most militarised teenagers in the world. The future pilots of the Second World War joined the Flieger-Hitlerjugend and began their training building and flying model gliders in order to learn the principles of flight. Afterwards, they graduated to a gliding test which involved being shot into the air attached to a simple glider wing. They used this to fly a short distance, and then come safely in to land. Eventually, the Flieger-Hitlerjugend graduated to flying gliders and piston-engined aircraft, all ostensibly in the name of boyish fun.

The degree of enthusiasm invoked in the ‘flying’ Hitler Youth was exampled by Alfred Wagner who was so keen to fly for the Fatherland that, during the Second World War, he volunteered for duty on every possible occasion.

‘When you’re young, enthusiasm takes you over. It’s like a driving force you can’t control. I volunteered for the Luftwaffe when I was 17. To me, it was a marvellous adventure. Flying was enormous fun, and I was full of enthusiasm for it, if we were asked to volunteer to fly somewhere, I was always first in the queue!’

The heroes young men like Alfred Wagner longed to emulate were the intrepid aces of the First World War whose daring in dog-fights with the enemy had made them into legends - Baron von Richthofen, the ‘Red Baron’, Verner Voss, Max von Muller, Ernst Udet and Hermann Goering, who later became head of the Luftwaffe.

Goering, who first met Adolf Hitler in 1922 and became a keen disciple, was the son of a diplomat. He made a distinguished name for himself in the First World War and became famous as one of Germany’s top air aces, with twenty ‘kills’ to his credit. At age twenty-five, after the ‘Red Baron’s’ death in action in 1918, Goering succeeded him as commander of the renowned Richthofen Squadron. Goering was commander for only four months before Germany’s defeat and surrender and his great personal vanity as well as his strong sense of nationalism were mightily offended by the terms of the Versailles treaty. Like many Germans, Goering felt the armed forces had been dishonoured and after falling under the extraordinary spell Hitler exerted over his followers, he joined the Nazi Party determined to right this wrong.

From Hitler’s point of view, Goering’s personal devotion and his exploits in the First World War fitted him perfectly to head the new Luftwaffe he intended to forge. With Ernst Rohm, another veteran of the War and chief of the SA, the Nazi stormtroopers, Goering became a principle lieutenant of the future Führer.

Although Goering was awed by Hitler’s personality and often acted like his minion, he had a charisma of his own which could fuel enthusiasm in others. One of those he personally inspired was Hajo Hermann, who later flew 370 missions with the Luftwaffe and downed ten Allied aircraft.

‘Goering actually determined my career as a flier. I was an infantryman and scrabbling around with a steel helmet and machine gun on the army training ground near Berlin. He rode up, wearing the uniform of an infantry general, and called down to me, ‘Well, what’s it like down there, then? Isn’t it a bit tough? Wouldn’t you rather come up here to me?’ and he pointed upwards towards the sky.

‘At the time, I had no idea who he was. We didn’t have television, so we weren’t familiar with the high-ups in the armed forces. But he pointed to the sky and said: ‘Up there, become an airman.’ And I said, ‘Yes indeed, Herr General!’ Shortly afterwards I was ordered to go to Berlin for an air force medical examination and then it began.’

Later, during the War, Hajo Hermann received special favour from Goering after he had developed the night-fighter technique known as the ‘Wild Boar’. This was an attempt to put a stop to the night bombing of Berlin by the Royal Air Force in 1943 and 1944, and involved the use of Messerschmitt 109s as nightfighters. Guided only by ground radio, the Me-109s successfully hunted down the RAF bombers. Hajo Hermann refined his ‘Wild Boar’ with camouflage: the undersides of the aircraft were painted black and an additional flame dampener was added over the exhaust stubs. Some of the Me-109s were equipped with a whistle device that helped the ground crews identify the Luftwaffe aircraft as they returned from their missions.

The ‘Wild Boar’ and its successes came to Goering’s attention and Hajo Hermann found himself shooting up the ranks.

‘Goering promoted me immediately, that happened quite rapidly. At the beginning of 1944, I was a captain and at the end of the year I was a colonel. He put me up for a higher decoration, which I was then awarded by Hitler.’

Hitler followed Goering’s recommendation even though, at that stage in the War, he was out of favour with the Führer. Hitler’s disillusionment dated from 1940, when, despite Goering’s swaggering and boasting about ‘his’ Luftwaffe, they had lost the Battle of Britain and therefore ruined the chances for another successful German invasion.

Hajo Hermann acknowledges that Goering made mistakes but this had no effect on his loyalty.

‘I cannot with the best will in the world make a disparaging judgment about this man because he did too many good things for me. He gave me his trust and raised me to higher positions. I don’t bear an absolute admiration for him, but as Shakespeare said, ‘Taken all in all, he was a man,’

In 1936, Hajo Hermann flew with the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion in Spain, where they supported the Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco and gave an awesome demonstration of what Europe could expect from a future war. The seeds of the Spanish Civil War, which began on 18 July 1936, had been sown five years earlier, when the rise to power of republican liberals had forced the King, Alfonso XIII, into exile. Franco, who proved to be a dictator in the Hitler-Mussolini mould, rebelled against the anti-militarist policies of the liberal government and invaded Spain from Spanish Morocco. In Germany, Hitler’s sympathies were naturally with Franco and the Condor Legion was detailed for ‘special duty’ in Spain.

The Legion consisted of four bombers squadrons, forty-eight aircraft in all, and four fighter squadrons backed by anti-aircraft and anti-tank units. With this, the curtain went up on a new and terrifying form of air warfare: the blitzkrieg, with its heavy bombing raids and dive-bombing tactics, as demonstrated by the Ju-87 ‘Stuka’. The First World War in the air had been a relatively gentlemanly business, with pilots jousting in dog-fights like medieval knights in the lists and adopting a chivalrous approach to their opponents. By 1936, all that had disappeared. The Condor Legion in Spain was out to terrorise, annihilate and paralyse the republican forces and on 27th April 1937 was accused of atrocity over the bombing of Guernica, the cultural and spiritual home of the Basques.

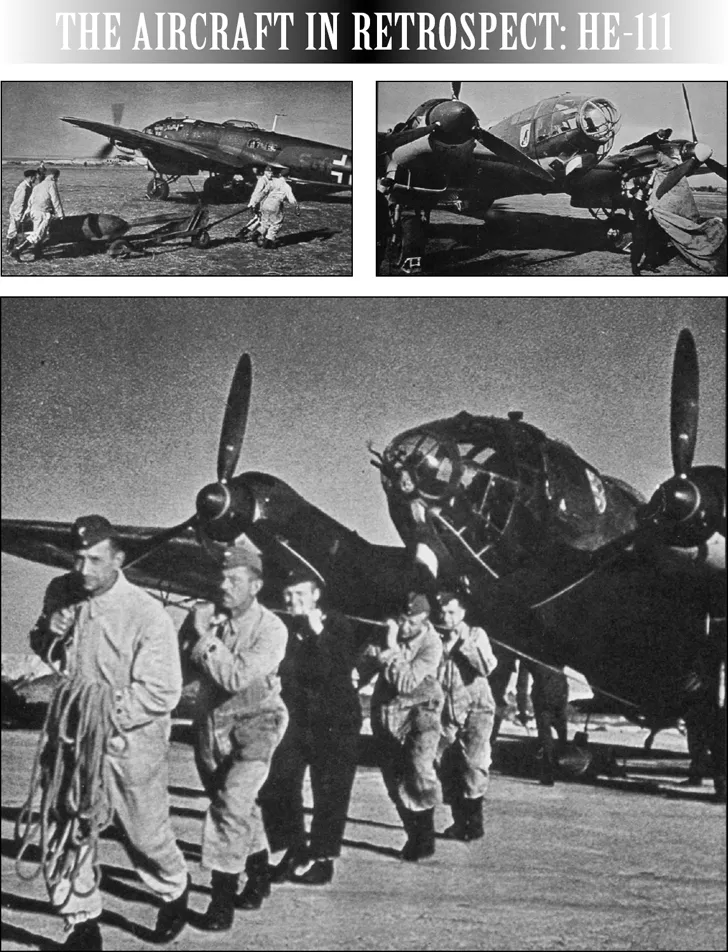

The He-111 was the most common bomber in service with the Luftwaffe. Although it was officially designated as a medium bomber this twin-engine machine was in fact the heaviest bomber, which was widely available to the Luftwaffe. Although this aircraft was never as common as the more successful Ju-88 it achieved much more fame. Designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter in the early 1930s it was often described as the “Wolf in sheep’s clothing”, as in the pre-war era it masqueraded as a transport aircraft in order to avoid the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles.

The He-111 is perhaps the most famous symbol of the German bomber force (Kampfwaffe) due its distinctive leaf like wing shape and “Greenhouse” nose, which gave excellent all round observation. The Heinkel 111 was the only medium/heavy Luftwaffe bomber during the early stages of the Second World War. lt proved reliable and efficient in all the early campaigns suffering only modest losses until the Battle of Britain, when its weak defensive armament exposed its vulnerability. As a combat aircraft the He-111 proved capable of sustaining heavy damage and remaining airborne. As the war progressed the He-111 was used in an ever increasing variety of roles on every front throughout the war and in every conceivable role. The He-111 saw service as a strategic bomber during the Battles for Poland, Norway, Holland and France. lt was heavily involved in the Battle of Britain, but also saw service as a torpedo bomber in the Battle of the Atlantic, a medium bomber and a transport aircraft on the Western Front, the Eastern Front and the North African Fronts. Later in the war, with the German bomber force redundant, the He-111 was converted to use as a transport aircraft and downgraded to a logistics role. Despite being constantly upgraded it became obsolete during the latter part of the war, but the failure of the Luftwaffe to design and produce a worthy successor meant the He-111 continued to be produced until 1944. Some 5600 of all variants were produced.

It was market day, and Guernica was crowded with visitors from the environs round about. Suddenly, it was later reported, the sky filled with Heinkel 111s and Junkers-52s, escorted by fighters, and the crowds in the town square were pounded with high explosives and strafed with machine-gun fire. Incendiary bombs rained down, setting fire to buildings. The Mayor of Guernica later told newspaper reporters: ‘They bombed and bombed and bombed.’

One reporter arrived in Guernica soon after the aircraft departed:

‘On both sides of the road, men, women and children were sitting, dazed. I saw a priest and stopped the car and went up to him. His face was blackened, his clothes in tatters. He couldn’t talk and pointed to the flames about four miles away, then whispered: ‘Aviones…bombas…much, mucho…’

Smoke, flames, the nauseating smell of burning human flesh and the dust and grit from collapsed buildings filled the air.

‘It was impossible to go down many of the streets, because they were walls of flame. Debris was piled high. The shocked survivors all had the same story to tell: aeroplanes, bullets, bombs, fire.’

Despite such dramatic reports, the bombing of Guernica became controversial when the Condor Legion denied involvement, even though the town contained military installations - a communications centre and a munitions factory - that could have counted as legitimate targets. Blame was ascribed instead to the Nationalists, who, it was said, had destroyed Guernica themselves. Experts called in to examine the ruins confirmed that the pattern of destruction evidenced explosions from the ground rather than from the air. However, the style and power of the attack on Guernica, as described, bore a chilling resemblance to the way the Luftwaffe later fought in the blitzkrieg campaigns against Poland and in western Europe. Then, it became clear, the destruction of Guernica, as reported, had been only a rehearsal.

Hajo Hermann found that the Condor Legion did not always have things their own way. The Republicans, too, were receiving aid from the outside. On receiving suitable payment in gold, the Russians sent them their best fighter, the Polikarpov 1-16 Rata. The Rata was the first in the world to combine cantilever monoplane wings with retractable landing gear at a time when almost all fighters were biplanes.

Hajo Hermann remembers what happened when the Luftwaffe aircraft had to confront the Rata, an aircraft the German pilots came to respect, with good reason.

‘The Polikarpov 1-16 Rata was the best plane that turned up in Spain. On one occasion, I was shot at by a Rata. It flew in an arc from in front of me, flying past and the rear gun was fired directly into the cockpit. Afterwards, there were quite a lot of bullet holes in my plane. Some of my comrades in the Condor Legion got as many as 250 bullets in battles with the Rata.

‘They were really hard planes to fight against. You couldn’t see them against the horizon. They used to come from Alcala de Henares, Getafe, the areas around Madrid and climbed up rapidly and you couldn’t really see them over that area. Then, suddenly there they were!

‘You couldn’t hear the Rata, either. That was the peculiar thing.

In the air, everything takes place absolutely silently, secretively, and then suddenly, from out of the silence, comes death. That’s what it was like. You thought you were watching the Ratas from a distance, then a tiny spot suddenly becomes enormous, with a huge engine in front of your nose, and they’re firing at you.

‘The Ratas often approached our planes head on. That was dangerous for us. We could defend ourselves very well from the rear. We had a rear gunner and down below in the bowl, in the ‘pot’ as we called it, we had an observer who could fire to the rear. We also had machine guns pointing out of the side windows but we were vulnerable in the front. That was why an officer on the General Staff, Kraft von Delmensingen, ordered machine guns to be fitted to our wings.’

The deadly nature of the Rata was made clear when Hajo Hermann was flying a JU-52 to attack a Republican position at Bilbao, in northern Spain.

‘Another of the Condor pilots flew in front of me to the left. Suddenly, the Rata flew between us and our man was a goner. His aircraft began to burn and immediately turned into a fiery, red ball. The plane just disintegrated and fell to Earth flaking into pieces.

‘It was a tremendous shock, but only for a tenth of a second or so, and it taught me a lesson for the future. When you’re flying in war, you have to keep on towards the target. That’s your duty and you must do it.

‘Of course, you know you can suffer the same fate - that’s the way war is. But it’s no good dwelling on it, even when you’ve just seen a comrade blown out of the sky. It always seemed to me to be so ...