- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

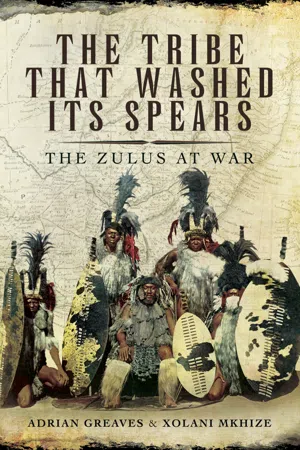

By tracing the long and turbulent history of the Zulus from their arrival in South Africa and the establishment of Zululand, The Zulus at War is an important and readable addition to this popular subject area. It describes the violent rise of King Shaka and his colorful successors under whose leadership the warrior nation built a fearsome fighting reputation without equal among the native tribes of South Africa. It also examines the tactics and weapons employed during the numerous intertribal battles over this period. They then became victims of their own success in that their defeat of the Boers in 1877 and 1878 in the Sekhukhuni War prompted the well-documented British intervention. Initially the might of the British Empire was humbled as never before by the surprising Zulu victory at Isandlwana but the 1879 war ended with the brutal crushing of the Zulu nation. But, as Adrian Greaves reveals, this was by no means the end of the story. The little known consequences of the division of Zululand, the Boer War, and the 1906 Zulu Rebellion are analyzed in fascinating detail. An added attraction for readers is that this long-awaited history is written not just by a leading authority but also, thanks to the coauthor's contribution, from the Zulu perspective using much completely fresh material. Skyhorse Publishing, as well as our Arcade imprint, are proud to publish a broad range of books for readers interested in history--books about World War II, the Third Reich, Hitler and his henchmen, the JFK assassination, conspiracies, the American Civil War, the American Revolution, gladiators, Vikings, ancient Rome, medieval times, the old West, and much more. While not every title we publish becomes a New York Times bestseller or a national bestseller, we are committed to books on subjects that are sometimes overlooked and to authors whose work might not otherwise find a home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Tribe That Washed Its Spears by Adrian Greaves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia moderna temprana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Emergence of the Zulus

Settlement of the area known as Zululand and Natal predates the formation of the Zulu kingdom in the late 1700s by several thousand years. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of African Bronze Age settlements in the Tugela River Valley and sites in KwaZulu-Natal, which suggest on the limited evidence available that Khoikhoi communities were already established in the region by AD 300. Historians believe the pastoral black African people, the Bantu, were relatively recent incomers to southern Africa but from whence these people came is, by and large, unknown. The Bantu movement southwards was the greatest known migration ever witnessed in African history; it probably commenced in the first millennium AD and its timings and route remain something of a mystery. Its cause was most likely a combined process of pressure from expansion, colonization and conflict in their original homelands. Why this Bantu migration occurred is a matter of conjecture. It is possible that they were driven from their distant lands in the north by a stronger tribe, leaving their property and cattle to the victors. Perhaps they had little choice but, because Bantu lives had always been based upon cattle, it appears they were well suited to a nomadic life.

This slow but progressive migration over some 3,000 miles lasted more than half a millennium and took the route from the arid lands sub-Sahara, south-east around the wastes of the Kalahari Desert, after which they passed by the verdant coastline of the Indian Ocean before expanding further south towards the Cape. During this migration the growing population naturally began to experience land pressure, which invariably led to inter-tribal conflicts and the search for more peaceful lands. Being pastoralists and with cattle forming the greater part of their life, they would have been able to make good their losses from weaker clans on their progression south.

The migrating Bantu people were recognizably similar to the main cultural and linguistic groups who inhabit the area today: the Xhosa to the south, the Sotho and Tswana in the interior, and the Nguni on the northeastern coastal strip adjoining the Indian Ocean. The Bantu, the Xhosa tribe, were still on their journey south, soon to reach the Great Fish River, the limit of Boer scouting, in 1769.

The eventual arrival of this aggressive cattle-owning society to the northeast of the Cape had an inevitably destructive impact on the two indigenous populations. The pastoral Khoi avoided conflict by moving further south while the hunter-gathering San, a branch of the Khoi, were gradually forced to abandon their costal area in favour of the more marginal environments of the Qahlamba Mountains, later named ‘Drakensberg’ by the Boers. Due to persecution by white and black alike for being diminutive, large numbers of the San crossed the Qahlamba to seek sanctuary in the only area left uninhabited, the inhospitable and arid Kalahari Desert. The survivors became known as ‘Bushmen’.

During this period of progressive migration and population growth, clans large and small naturally expanded and then split into smaller clans, which, as they grew, then had to repeat the cycle of competing against each other for increasingly scarce resources, such as land for cattle and crops. By this process, the Hlubi clan under inkosi Bhungane became the dominant tribe in northern Natal, extending its sphere of influence by subjugating lesser groupings until it dominated an area of 3,000 square miles.

While the main migration was still moving south, one comparatively small Nguni tribe, the Mtethwa (estimates suggest between 150 and 200 clans), split away and headed east towards the coast. One such clan would become the Zulus. The beginnings of Nguni development in the area known as Zululand can be identified as circa 1790-1830, just as the main Xhosa migration reached a point a mere 500 miles from the Cape. Unbeknown to the Xhosa, the land they were approaching to the southwest was already in the process of being colonized by the Dutch. But for a few years, the Xhosa could have been the first people to reach the Cape and African history would have turned out be very different.

Meanwhile, the breakaway Mtethwa tribe and its clans, all speaking a particular dialect and walking in step with their customs, began settling the lush land between the Drakensberg and the Indian Ocean. Due to the richness of their land the social development and wealth of the Mtethwa steadily expanded, even though they were quick to resort to force when necessary. One of these clans included an insignificantly small group of between 100 and 200 people who had settled themselves along the banks of the White Mfolozi River and in sight of the Indian Ocean. Their chief, Mandalela, had a son, Zulu, who eventually succeeded him and under whose chieftaincy the small group thrived. According to Zulu folklore, the clan adopted the title ‘Zulu’. Chief Zulu was followed by Mageba; Ndaba followed Mageba, who was followed by Jama. During this embryonic stage of Nguni development, the Mtethwa clan had grown in size to more than 1,000 people and by the end of the eighteenth century probably amounted to 3,000 or 4,000 living under the aged chieftaincy of Jobe. Jobe had a number of sons, including Godongwana and Utana, who were over-eager to assume the mantle of chief. Apprehensive for his own safety, Jobe dispatched loyal warriors to kill his two ambitious sons but Godongwana escaped, severely wounded, to take refuge with the Hlubi clan near the Drakensberg Mountains while Utana died suddenly of a mysterious illness. In order to avoid detection from his vengeful father, Godongwana changed his name to Dingiswayo (meaning ‘one in distress’). Dingiswayo remained with the Hlubi until his father died and then returned home to find another brother, Mawewe, on the throne. Meanwhile, Dingiswayo had acquired both a gun and a horse from a white trader – items that were unknown to the Mthethwa. Mawewe fled in fear for his life but he was tracked down by Dingiswayo and killed. In the midst of this turmoil, the chief of a fledgling Zulu clan, Senzangakhona, unwittingly started a chain of events that would dramatically affect southern Africa.

In 1787, Senzangakhona dallied with the daughter of an eLangeni chief, in itself a relatively insignificant event but one that would have major implications for the future of the Zulu people. The unfortunate girl, Nandi, soon fell pregnant, but marriage was impossible because she was a not a Zulu. After Nandi gave birth to a son, the eLangeni banished the disgraced Nandi and her child, which morally forced Senzangakhona to appoint Nandi as his’ unofficial’ third wife. She was unable to get her son recognized or named by his father, so in defiance Nandi named him ‘iShaka’ after a common intestinal beetle. Nandi also bore Senzangakhona a daughter but the family lived a lonely and unpopular life until her equally despised son, Shaka, now in his early teens, lost some goats belonging to Senzangakhona. Such was the chief’s anger at this youthful carelessness that Nandi and her children were evicted back to the unwelcoming eLangeni, who delighted in making life for the outcasts even more miserable.

By 1802, the starving eLangeni could no longer tolerate Nandi and her family so banished them into destitution at a time when the whole land was suffering widespread famine. Nandi fled to the Qwabe clan, where she had once given birth to a son by a Qwabe warrior named Gendeyana. Under Gendeyana’s guidance, Shaka developed into such an excellent warrior that Senzangakhona sought the return of this fine young combatant, whether to develop his skills or, more likely, to murder him is unclear. Nandi’s suspicions led her to move her family to the protection of yet another clan in order to protect Shaka from his father.

At the very beginning of the 1800s, Dingiswayo assumed the mantle of chief of the Mtethwa tribe and immediately set about training his force of 400 warriors and, by a sustained policy of subjugation and making threats of annihilation, he gradually assimilated the surrounding tribes. He became a politically astute leader who replaced recalcitrant chiefs with his own kind, usually favoured and trusted sons from his several hundred wives. It was Dingiswayo who first developed a liking for European goods and began trading elephant tusks for trinkets with the passing Portuguese traders from their Delagoa Bay settlement 200 miles to the north.

Within the clans, especially the growing Zulu clan, they developed complex social structures. They were competent cattle farmers with no concept of money, aspirations or worries; nature provided everything. They were able to make implements out of metal, the very best of which was virtually equal to steel. One of these items, the throwing spear, would soon ensure their ascendancy over their neighbours and any San and Khoikhoi they encountered, and would soon seriously inconvenience the encroaching whites.

Their social structure valued a form of marriage – a concept orientated more towards property than the values of conventional European marriage. Its complex system of dowry payments for a wife, known as lobola, ensured that a man could not marry until he was established in society and possessed sufficient cattle, the Zulu currency, to pay the required lobola. The more cattle a man had, the more wives he could buy. Most Zulu men had only two, or at the most, three, wives, to whom fell the hard physical work of planting and raising crops, while the task of tending cattle was the exclusive preserve of the youths, on behalf of the men. Under the emergence of the extended Zulu kingdom early in the nineteenth century, cattle seized from outsiders were regarded as property of the state for the king to dispose of as a reward, or to farm out to district chiefs who would care for them. It was this Zulu dependency on cattle for the vital lobola for social prestige and their subsequent wealth that was soon to bring the Zulus into permanent conflict with the surrounding Nguni tribes and, in due course, the advancing Boer trekkers.

Administratively, power was devolved from the tribal leader with diminishing power to each Zulu homestead chief and thence to all the scattered homesteads within their boundary. From the chief to the farmer and his family, all recognized themselves as part of a wider clan, a selfsufficient group living in a classless society. Zulus would explain their origin from the collective belief that they could trace themselves back to a common ancestor, real or imagined, who had two sons, Qwabe and Zulu. Each brother struck out on his own to establish his personal following. These two groups duly became known after their founding father, Zulu, the people calling themselves amaZulu (people of Zulu). Zulu means ‘the heaven’ or ‘the sky’. Their beliefs were their means of explaining the reason for their existence and this belief is still widely acknowledged.

Each clan had its dominant lineage within the families, and it was from such that the male line of hereditary chiefs was drawn. Several small neighbouring clans, linked by ties of kinship, would form a chiefdom; the chief of the dominant clan in the area would have been the overall leader. This chief controlled the political and administrative life of the clan by heeding the advice of his ‘inner council’, although his decision in any dispute or clan matter was final.

A clan or homestead, the umuzi, would be largely self-sufficient with each homestead producing sufficient crops and managing their cattle to support themselves. Their domestic and farming tools were made within each umuzi; the only essential product not made at home was iron, which was necessary for the production of hoes and spear blades. Even this seems to have been readily available. One clan was renowned as metal workers – the Cube people, who lived in the Nkandla Forest, north of the Tugela River. As was common among African cultures, the Zulus regarded the forging of iron with superstition, and the smiths, keen to maintain the mystique of their trade, lived and worked away from ordinary dwellings. Ritual was an essential ingredient in the process, and it was widely believed that the most successful spear-blades were tempered with magical herbs and human fat to increase their efficacy.

Zululand was superb cattle country with freshly watered grasslands producing a succulent range of sweet and sour grasses. These pastures allowed the Zulu people to raise their stock without migrating any great distance and the relative absence of tsetse fly and other parasitic pests kept bovine mortality levels to a minimum. It was fortuitous that the Zulus were competent cattle farmers as their survival and prosperity depended on their cattle; cattle were not only an important source of food – although rarely for their meat except for special occasions and sacrifices. Their milk was drunk and curds, or amasi, formed an important part of their staple diet. The cattle provided hides for shields and garments, tails were a component of festive dress, and horns were used as containers for medicines or gunpowder. The ritual sacrifice of cattle to the ancestors was a common ingredient of a number of ceremonies, either pre-battle or to ensure harmony with the dead.

Such was the importance and value of their cattle that the physical layout of the umuzi was traditionally arranged in a circle around a central cattle pen. At the lowest level of Zulu society, a typical umuzi probably consisted of no more than four or five huts of a family unit, the married man together with his immediate family and any dependants. Within a particular clan, usually inter-related, one homestead would be close to the next with several on one hillside, usually overlooking a river or stream. All umuzi across Zululand were built along the same lines, and can still be seen today across rural Zululand. If the umuzi headman, the umnumzana, was sufficiently wealthy he would have his personal hut at the furthest end of the umuzi. Next in line was the hut of the principal wife, with the huts of lesser wives arranged in descending order of seniority. At the furthest point of the umuzi from the umnumzana’s hut were the huts of unmarried dependants. In an ordinary umuzi the hut of the chief wife was his main place of abode although he would, at whim, visit the huts of his lesser wives.

Across Zululand the reeded thatched huts were all traditionally domeshaped and circular, with a low arched door to defend or politely force a visiting guest to bend in homage. (Genuflection has always been part of Zulu culture.) The design ensured that the hut was cool in summer and warm in winter and consisted of a rounded framework of bent-over saplings with the ends bound together where they criss-crossed. If the hut was of any size, a large pole would be used to support the interior. The thatch would last for several years before needing to be replaced. The floor area was smeared with cow dung, which was then polished with stones to produce a rock-hard dark glaze. A raised dais in the centre served as a hearth but, without a chimney, smoke would have hung in the thatch, which had the advantage of keeping the huts pest-free. Each umuzi was selfcontained and, by necessity, self-supporting. Work around the umuzi was clearly delineated. The men were the artisans and pastoralists who provided and maintained the huts and tended their cattle. Women were the housekeepers and agriculturalists, the growers, gatherers of food, water and wood, and the umuzi cooks. Until more recent times, fish had not been an acceptable source of food among the Zulus. As long ago as 1820, the Reverend Kay wrote:

They have as great an antipathy to fish as to swine’s flesh; and would as soon think of sitting down to a dish of snakes as to partake of any of the inhabitants of the deep.2

To the south, the situation changed between 1816 and 1824; the Cape Frontier Wars were fought between blacks and whites, both keen to extend their area of domination. While the more northerly Nguni chiefdoms were immune from the effects of these ongoing conflicts, the Nguni people were not immune from the growing pressure created by their own expanding populations. With resources being limited, internecine violence, later known as the Mfecane, resulted.

Chapter 2

Shaka and the Second Mfecane

The brutality of the Mfecane, a Zulu word for ‘disturbance during the rise of the Zulu people’, brought with it unremitting pressure for clans to expand and survive the growing incidence of inter-tribal rivalries. It was a long drawn-out process that took effect over 150 years. Under the Zulus it became a process of creeping domination.1 The term could also be a neologism2 from the Sotho word Difaqane (the scattering) and the Tswana Lifaqane (time of migration).3 The two words are sometimes seen as interchangeable.4 The term Mfecane is generally applied to the whole of southern Africa, or sometimes just to the eastern coastal regions, whereas the term Difaqane is applied to the Highveld.5 This uncertainty about the choice of a word is merely academic. It is insignificant when compared with the blatant savage reality of the Mfecane – the effects of which would reach as far as Swaziland, Lesotho, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania, and involve the loss of more than a million lives.

The first inter-clan violence to involve the Zulus took place in the 1790s, during a period of prolonged drought, remembered by the Zulus as the Madlantule, meaning ‘suffer hunger but do not speak’. With clans increasingly suffering the effects of the drought, survival was the people’s foremost priority. The advantages in maximizing the territory each group controlled became clear, either through alliance with neighbours in a similar position, or through direct conquest. The survivors faced starvation and cannibalism while, in some areas, villages grouped together to protect their grain stores or moved to abodes elsewhere. Two tribes in particular, the Ndwandwe of Chief Zwide and the Mthethwa of Chief Dingiswayo, were among the first to develop in size and influence, and in 1810 their own pressures to expand and inter-tribal rivalries between them soon spilled over, involving their neighbours such as the Ngwana people living along the White Umfolozi, the Cunu and Tembu to the west and the Qwabe to the south. Rather than submit to overwhelming aggressors, the Ngwana chose to move into Hlubi territory, in turn shattering that society. Likewise, the Qwabe living along the Tugela River consolidated their chiefdom by conquering the weaker neighbouring Thuli and Cele tribes. They, in turn, invaded their neighbours in an explosive pattern that was to wreak havoc and cause misery across southern Africa, with the victors of the day killing vanquished male warriors and absorbing the surviving women and children in the process.

In 1824 the traveller Fynn wrote:

The region devastated by marauding chiefs exceeds the Cape...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Maps

- Foreword

- Zulu Names

- Timeline of Events Significant to the Zulu People

- Glossary of Terms

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Emergence of the Zulus

- Chapter 2: Shaka and the Second Mfecane

- Chapter 3: Zulu Rituals and Customs

- Chapter 4: White Expansionism in South Africa and the Eight Frontier Wars

- Chapter 5: Passing the Crown: From Kings Shaka, Dingane and Mpande to King Cetshwayo

- Chapter 6: The Emergence of King Cetshwayo

- Chapter 7: Defending their Nation

- Chapter 8: Isandlwana

- Chapter 9: To Rorke’s Drift

- Chapter 10: Nyezane and Gingindlovu

- Chapter 11: Ntombe, Hlobane, and Khambula

- Chapter 12: The Zulu Defence of Ulundi, and the Prince Imperial Louis Napoleon

- Chapter 13: The Battle of kwaNodwengu – Ulundi, 4 July 1879

- Chapter 14: Beginning of the End

- Chapter 15: Closure of the Zulu War

- Chapter 16: Long Live the King

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography