- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This new paperback edition brings the history of Henry VIII's famous warship right up to date with new chapters on the stunning presentation of the hull and the 19,000 salvaged artefacts in the new museum in Portsmouth.Mary Rose has, along with HMS Victory, become an instantly recognisable symbol of Britain's maritime past, while the extraordinary richness of the massive collection of artefacts gleaned from the wreck has meant that the ship has acquired the status of some sort of 'time capsule', as if it were a Tudor burial site. But she is much more than an archaeological relic; she was a warship, and a revolutionary one, that served in the King's navy for thirty-four years, almost the entire length of his reign.This book tells the story of her eventful career, placing it firmly within the colourful context of Tudor politics, court life and the developing administration of a permanent navy. And though the author also brings the story right down to the present day, with chapters on the recovery, the fresh ideas and information thrown up by the massive programme of archaeological work since undertaken, and the new display just recently opened at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, it is at heart a vivid retelling of her career and, at the end, her dramatic sinking.With this fine narrative and the beautiful illustrations the book will appeal to the historian and enthusiast, and also to the general reader and museum visitor.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Warship Mary Rose by David Childs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Birth of Greatness

HENRY WANTED WAR. Whatever his other aims and ambitions on ascending to the English throne none was more obvious to observers than this. Henry VIII was not overly concerned about whom his enemy might be as long as he had one, but there were certain parameters even his youthful hot head had to take into account. His cautious father, Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, had ensured that England was neither a threat to or in danger from her enemies. The new king’s elder sister, Margaret, was married to James IV of Scotland, which put that traditional enemy of the English in check for the time being. Henry himself was married to the king of Spain’s daughter, Katherine of Aragon, which precluded Iberia from any direct conflict; the Holy Roman Empire was too amorphous; and the Turks were at too great a distance for England to undertake a crusade in that direction. This left France – another traditional enemy – as the likely candidate for war. Henry just needed an excuse, and the opportunity. The Venetian ambassador to England, Andrea Badoer, recognised this, writing to his masters on 25 April 1509, just three days after Henry had been proclaimed King: ‘The King is magnificent, liberal and a great enemy of the French. He will be the signory’s friend.’1 While on the next day another Venetian stated in a letter quite clearly that: ‘The King swore, de more, immediately after his coronation to make war on the King of France. Soon we shall hear that he has invaded France.’2

Henry was even reported to have retained some Venetian trading galleys at Southampton for the express purpose of using them to load troops for a French invasion. But why? England was not threatened. In continental Europe, the current cockpit of confrontation was northern Italy, not the Channel coast and the Low Countries – areas in which Henry would have had a legitimate interest. The motivation for this bellicose stance was a personal desire for the prestige of success in arms. In taking to the field of battle, sixteenth-century princes gauged their self-esteem and gained respect from other monarchs. Henry believed that the time he spent in the tilt yard and hunting, as well as his many suits of mail, were very much a part of his kingly duties and regalia. Coupled with this was the young king’s loathing of the elderly Louis XII of France, whose gout-ridden feebleness Henry saw as an affront to the very idea of kingly virtue. Moreover, in 1509 Henry VIII had much to prove if he were to be counted among the great princes of Europe.

A model of Henry VIII in his prime, based on the well-known Holbein portraiture.

Had Henry VIII wed five fewer wives, sired two fewer children and defended only one faith he would probably be remembered as an insignificant, unpleasant Catholic king of a backward peripheral nation, which he bankrupted in pursuit of unrealised foreign fame. His European peer group were far more significant individuals. In the last decade of the fifteenth century, along with Henry, three other princes were born who were to play major roles in the future of Europe once, in their teens or early twenties they had ascended to their inheritance. Süleyman became the Ottoman sultan at the age of twenty-five in 1520; Francis I, king of France at nineteen in 1515; Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire (longhand for the German states) was only fifteen when he became the Spanish king in 1515; while Henry himself was just seventeen when he inherited the throne of England. Of the four, Süleyman’s rightfully earned sobriquet ‘the Magnificent’ sets him apart from his peers who spent a large part of their reigns warring both against him but, principally, amongst themselves. These latter wars were largely centered around lands in Italy where Francis was to achieve one glorious victory, at Marignano in 1515, and one catastrophic defeat, at the hands of Charles, at Pavia in 1525.

During these turbulent times the English king was to remain a secondary player, rather like a child clinging on to the legs of two struggling adults in an attempt to influence the outcome. As a military leader Henry laid siege to a Flemish town, Tournai, and a French village, Thérouanne; fought one battle, The Spurs, in which the sides scarcely clashed; seized one French ferry port, Boulogne, and retained a tenuous hold over another, Calais. Although Henry was paid handsomely to return his gains these forays, which bankrupted England, are scarcely more than a footnote in contemporary European history. This was minor stuff indeed compared with the dynastic struggle between the houses of Hapsburg and Valois to establish hegemony over the whole of western Europe. After the deaths of those four rulers, (Henry and Francis in 1547, Charles in 1558 and Sulyeman in 1566), contemporaries would have ranked Henry as the least significant of the four. The contempt with which the English were held by the European super powers is best summed up in the words of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian, to his grandson and successor, Charles, in the spring of 1517 when he remarked about the terms of the recent Treaty of Noyon, ‘My child, you are about to cheat the French and I the English.’

The capture of Boulogne was one of Henry’s most positive military achievements, although it led Francis I to attempt the invasion of England in 1545. The original from which this engraving was made in 1788 was commissioned by the same man as the better known panorama of the Mary Rose’s last battle, the so-called Cowdray engraving.

© 2007 www.artistsharbour.com www.artistsharbour.com from whom prints are available.

At the end of his life Henry VIII bequeathed to the nation four things of lasting significance: a national Church; a countryside of romantic ruins,3 a daughter, Elizabeth, who was to achieve for the nation the greatness that Henry could only dream about; and, in the navy royal, a legacy greater and more lasting than any left by his contemporary dynastic rivals. It was not a legacy easily or rapidly created given the international position that England occupied throughout his reign and her lack of ocean-going ships and sailors. The limitations of England’s sphere of influence can be seen by studying the imperial and maritime achievements of other European powers during Henry’s lifetime. In 1492 Columbus discovered America for Spain; in 1499 the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama returned from the East Indies; in 1500 Brazil was discovered; between 1514 and 1517 the Turks seized Egypt and Syria; in 1520 the Spaniard Cortes conquered Mexico; in 1529 the Turks besieged Vienna; in 1533 Pizarro overthrew the Incas. The list goes on, and it is one of extraordinary achievement in this one sphere of endeavour alone. Add to it developments in art, architecture, religion and philosophy, and the minuteness of the English contribution becomes starkly clear.

At the beginning of Henry’s reign, England had a long way to go before she could contribute to this list of seminal events or join the ranks of the great players. By the end of the Tudor century, she was poised to dominate them. Henry, without understanding its potential, laid the foundation for England’s greatness through the creation of the standing navy royal, and was blessed that, in Elizabeth, he had an heir able to build magnificently upon this foundation. Henry’s treatment of his own inheritance demonstrated all the characteristics of a second-generation heir to a thriving business thriftly assembled. He blew it. Whereas his father had fought to establish the family firm and had taken no chances with its fortune, which was significant at the time of his death,4 Henry was to show little interest in how the business was run, preferring to spend his inheritance in courtly delights such as the joust and chase at which he excelled. Standing at over six foot and possessing an athletic build the king could match any man in the tilt yard, archery butts, or other knightly venues, the pursuit of which often occupied his whole day leaving little time for tedious matters of state. Henry would thus not be a model ruler along the lines laid down by Renaissance philosophers. He was a man of action, not contemplation, but his willingness to delegate, idle though its origins may have been, was a key element in the transition of the English state from an autocratic kingdom to a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, well ahead of its European counterparts.

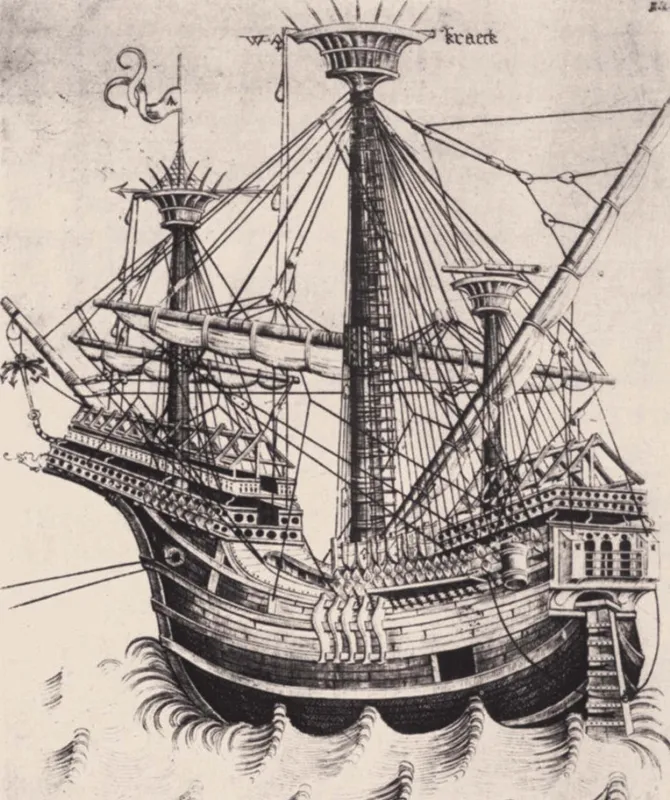

The best-known image of a late fourteenth-century merchant ship, this depicts a Flemish ‘Kraek’ (or carrack).

Henry was fortunate in finding, first in Thomas Wolsey, then in Thomas Cromwell, two men to whom he could entrust those matters of state that he himself found too boring. They would serve him well. Not that, in the end, their service would count for much when they let their monarch down. For Henry, among his many virtues was also a cruel and calculating bully, whose sleep was not disturbed by signing the death warrants – often on trumped-up evidence – of those who, having served him well, had become an inconvenience. Indeed, if one were to seek a modern equivalent of Henry VIII, one could find many similarities in the behaviour of an Idi Amin or Sadaam Hussein, bullying, pompous leaders of less significant nations. But, however uneasily rested the heads that advised the crown, Henry was establishing the necessary domestic conditions and relationships for a modern state.

Internationally it was a different story. Here Henry was personally active in pursuing an aggressive foreign policy, but he lacked an army or commanders who could achieve his goals. England, a land so frequently at war with itself, did not trust standing armies. It was also protected from all but the Scots by the Channel, which served it like a fortress moat. Henry’s foreign policy would depend, not for its success, but rather for its avoidance of failure, on the existence of a standing navy that was, towards the end of his reign, able to repel an invasion by a foreign force greater than that of the more famous Spanish Armada of his daughter Elizabeth’s reign. Henry was the first English ruler to appreciate that the state would be better served if war ships were a permanent part of the king’s armoury.

English monarchs required war ships for five reasons. These were to (i) transport an army; (ii) raid enemy coasts and towns; (iii) defend against invasion; (iv) protect trade and curb piracy, and (v) display the king’s prestige. It had always been possible to achieve these aims, for a limited period, with ships hired for the occasion from the nation’s merchant fleet and fitting them with pre-fabricated castles to hold soldiers. Even where such castles were not available they were easy to construct. Fir poles were lashed together to form a lattice cage which was fitted onto the ship’s deck. Upon this was secured a plank floor enclosed with a crenelated breast-work to protect those mustered inside and to give them a raised platform from which to pour down arrows and gun fire onto an enemy’s decks. That these castles were light meant that they had minimum effect on the ship’s stability. Later, when a permanent naval force was desired, the castles were built as part of the main structure, creating a purpose-built warship with limited use as a merchant vessel. The potentially hazardous disadvantage of this was that the resulting heavier structure might be considered capable of carrying weapons whose weight, located high up, could adversely affect the ship’s stability.

To facilitate his commandeering of merchant ships the king paid a bounty to merchantmen that entitled him to take up their vessels when he needed to transport his forces abroad. The amount payable varied, but was generally agreed at five shillings per ton; which indicates that it was a very expensive option for the sovereign, not lightly undertaken. In addition, the king was a shipowner in his own right, and able to use his few vessels either for his own trading or by leasing them to merchants. So, although the need for and concept of a permanent navy royal with a paid crew was recognised, it was a responsibility which earlier sovereigns chose to avoid. Henry VIII made it a reality in a reign in which all five reasons cited earlier for the possession of a fleet were to be evident.

The creation of a standing navy carried with it responsibilities over and above that of the manning, maintenance, and arming of the ships and the payment of their crews. Foremost among these was that of victualling, and Henry’s ‘naval staff’ were constantly being harassed by the sea-going admirals to provide the food and drink necessary to keep the fleet active and healthy. But a cadre of sailors dependent on the king for their well-being created other responsibilities as the Act for Maintenance of the Navy of 1540 made clear:

The maintenance of my master mariners making them expert and cunning in the art and science of shipmen and sailing, and they, their wives and children have had their living of and by the same…and have also be...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Picture Credits

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword by HRH The Prince of Wales

- Introduction

- 1 The Birth of Greatness

- 2 From Tree to Sea

- 3 Ballocks, Bows and Bastards

- 4 Captains and Commanders

- 5 Masters of the Narrow Seas

- 6 A Life in the Day of …

- 7 Sailing on their Stomachs

- 8 ‘A Noble Man Ill Lost’

- 9 A Fleet in Fear

- 10 Biting Back

- 11 A Nation in Need of a Moat

- 12 The Last Battle

- 13 Drowned Like Ratten

- 14 Rediscovery and Recovery

- 15 Home and Dry

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Notes and References