eBook - ePub

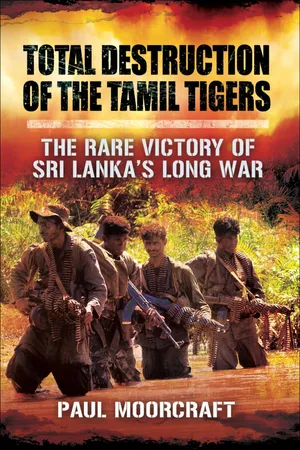

Total Destruction of the Tamil Tigers

The Rare Victory of Sri Lanka's Long War

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 2009, the Sri Lankan government forces literally eradicated the Tamil Tiger insurgency after 26 years of civil war. This was the first time that a government had defeated an indigenous insurgency by force of arms. It was as if the British army killed thousands of IRA cadres to end the war in Northern Ireland. The story of this war is fascinating in itself, besides the international repercussions for terrorism and insurgency worldwide. Many countries involved themselves in the war to arm the combatants (China, Pakistan, India, and North Korea) or to bring peace (US, France, UK, and Norway).While researching this work Professor Moorcraft was given unprecedented access to Sri Lankan politicians (including the President and his brother, the Defense Permanent Secretary), senior generals, intelligence chiefs, civil servants, UN officials, foreign diplomats and NGOs. He also interviewed the surviving leader of the Tamil Tigers.His conclusions and findings will be controversial. He reveals how the authorities determined to stamp out Tamil Tiger resistance by whatever means frustrated the media and foreign mediators. Their methods, which have led to accusations of war crimes, were brutally effective but are likely to remain highly contentions for years to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Total Destruction of the Tamil Tigers by Paul L. Moorcraft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Background to the War

Sun, sand and sea ... and monsoons

Despite romantic imperial connotations as the ‘pearl of the Indian Ocean’, the island has suffered from millennia of religious, ethnic, caste and class conflict. Peace has intruded as well, mainly under colonial rule, though historians are forbidden to mention that because of union rules and PC regulations. Sri Lanka has had many names, often reflecting whoever was in charge of most or just some of the island or sometimes merely because of the linguistic quirks of travellers and mapmakers. Early explorers all attested to the island’s physical charms, however. As Portugal’s national poet, Luis Vaz de Camões, noted (in translation):

Ceylon lifts her spicy breast,

And waves her woods above the watery waste

This is an apt summary of an island of mountains, forests, lagoons and sea. The land mass is 65,610 square kilometres (25,332 square miles); the coastline comprises 1,056 miles which was handy for all the seaborne invaders. In Sanskrit the country was known as ‘Tambapanni’ because of the copper-coloured beaches. Later, visiting Greeks and Romans called it ‘Taprobane’, although Ptolemy’s famous second-century AD map inscribes it as ‘Taprobanam’. Arab sailors called it ‘Serendib’, a corruption of the Sanskrit ‘Sinhaladvipa’. The Portuguese settled on ‘Celao’, which had begun as ‘Si-lan’ (a Chinese version) and was transformed by medieval travellers such as Marco Polo into ‘Seylan’. The English version – ‘Ceylon’ – was the modern compromise. The Sinhalese had long called their land ‘Lanka’ and the country was officially renamed in 1972 as ‘Sri Lanka’ (the prefix means ‘holy’ or ‘beautiful’). The state became formally (in English) the ‘Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka’ in 1978.

Despite its travails, foreigners were irresistibly drawn to the country. Arthur C. Clarke lived there because he was sucked in: he believed that parts of the island had an extra-strong gravitational pull. The science-fiction writer mapped out much of the future in a place where Clarke felt at home for nearly fifty years. Sri Lankans may well find Clarke’s views on gravity-plus persuasive, because they are deeply superstitious and often obsessed by astrology. More conventional modern visitors, ‘tourists’ if you must, would notice first the apparently homicidal driving, especially the trishaws. From their drivers’ windscreens dangle a variety of charms – Jesus, Buddha, Ganesh and the odd guru. They need all the divine insurance they can get. Tourists would also be told: ‘In areas of “human-elephant conflict” do not venture out after dark.’ While Clarke pontificated on black holes, many guidebooks of the last decades simply left blank large parts of the country, especially the north, especially at night. That was the permanent but unmentionable elephant in the room – the war.

The island has endured many unconventional visitors and not just war tourists, though most used to come in search of booty. Early explorers relied upon trade winds – aptly named for the ancient seafarers often had to wait a long time to catch winds back to Greece, China or Arabia. They came for spices and gems, but their becalmed ships often forced them to mingle with the local cultures and especially the women. If the topography allowed for easy naval incursions, the climate also influenced military campaigns inland. The low mountains were dumping grounds for the monsoon rains. Sri Lanka is unusual in that it has two monsoon seasons, coming from different directions at different times. The modern capital, Colombo, and the southwest get soaked from April to October. The east coast is drenched from November to January. The monsoons mark out what seasons the country has. Because it is so close to the equator, the temperatures are high throughout the year, with an average of 27C (80F), though often the humidity makes it feel much hotter. Understanding the sometimes steep, often wooded/jungle topography and the difficulties of soldiering in humidity, heat then torrential monsoon rains, makes it clear why sometimes the terrain and climate stalled the fighting in the long civil war. It is also a relatively crowded island: the size of Scotland but with four times the population (around 20 million).

The rulers: from the Stone Age to 1948

An indigenous Stone Age culture can be traced back to 10,000BC; a few hundreds of this Veddha people, related inter alia to the indigenous tribes of Australia, have survived, just, until today. The first Sinhalese arrived in the country in the sixth century BC – probably from northern India. Buddhism, later to become a powerful religious influence in the country, came in the mid-third century BC. A great civilization grew up around the cities of Anuradhapura (a kingdom from 200 BC to AD 1000) and Polonnaruwa (1070 to 1200). In the fourteenth century a south Indian dynasty established a Tamil kingdom in Sri Lanka’s northern areas, closest to the Indian mainland.

The previous three sentences are extracted from a Central Intelligence Agency summary of the country’s history. This might be suitably neutral and even anthropologically correct, but it would not be sufficient for a history overpopulated with foundation myths. In shorthand, the lion people (sinha is a lion) vied for supremacy with the tigers, the symbol of the early Tamil settlers; it was also a supposed ethnic clash between Dravidians and Aryans, which later played into the hands of those who portrayed the Sinhalese majority as proto-fascists.

Few (sane) Western historians, without an incisive knowledge of the country’s early history, and a detailed command of the relevant languages, would attempt a definitive conclusion about the historical precedents for Sinhalese and Tamil claims. Both sides can display a fanatical fervour (and fantastical fervour, for example regarding medieval flying machines or the power of holy relics) when it comes to establishing who came first and with what religious sanction. It is somewhat like the antagonists in the Balkan wars of the 1990s – few could discuss any military campaign there without reference to events of hundreds of years before, and often with the aid of maps, perhaps dating to the division of the Roman Empire. Yet much of the Balkan ethnic hostility had been whipped up by partisan politicians and media dating from the 1980s. Likewise, much of the Sri Lankan fratricide could be traced to events which followed independence in 1948, especially regarding language rights.

Relying totally on the CIA summary would be inadequate. Tamil military leaders were powerful as far back as 200 BC, and a successful Tamil invasion took place from AD 432; although Year One of the Buddhist era in Sri Lanka is 543 BC. The first entries in the Mahavamsa (‘Great History’) date from this time, and the arrival of the Sinhalese led by Prince Vijaya. The first Sinhalese royals traced their lineage to a union between a handsome lion and an amorous princess.

In the modern period, a crucial date was 1505, the arrival of the Portuguese who soon occupied parts of the coastal areas. Nevertheless, indigenous kingdoms, especially the polity centred on Kandy, resisted this encroachment. After 1656 the Dutch defeated the Portuguese on land and at sea, and foreigners secured a tighter grip of the island, though Kandy, hidden in deep jungle, continued to rule itself, along with some strange customs. In 1660 a young sailor from London named Robert Knox was held in Kandy for nineteen years. He recounted his often favourable impressions of the kingdom in a journal. An exception was his description of occasional deaths by elephant: executions by trampling or goring. His journal was filched in part by Daniel Defoe as the basis for Robinson Crusoe.

In 1796, the British — concerned about revolutionary France’s ambitions — wrested the island from the Dutch. As a bonus, the coveted natural harbour at Trincomalee became a Royal Navy staging post. In 1802 Ceylon was declared a British Crown Colony. In 1815 the last king of Kandy was deposed and exiled, though guerrilla wars spluttered on. The last rumblings of resistance were inspired by a (false) rumour in 1848 that women were to be taxed according to the size of their breasts – which perhaps indicated some of the less lofty preoccupations of the British colonizers.

On a more positive note, the British did their usual civilizing thing – not least building roads and railways. In comparison with India, Ceylon was far more intensively colonized as witnessed by the dramatic transformation of the landscape that occurred with the establishment of the plantation economy. The central highlands were changed from forest to farm. Tens of thousands of Tamils were imported from south India to work on first the coffee and then the far more successful tea plantations. The ‘new Tamils’ did not integrate well with the existing minority Tamil population, not least because the incomers soon almost equalled the numbers of indigenous Tamils.

In 1915, the centenary of the abdication of the last independent king of Kandy, fired up by overzealous Buddhist nationalism, Sinhalese mobs attacked Muslim traders in the southwest. From then on, the Muslims were usually caught between the more aggressive demands of the larger Tamil minority and the dominant Sinhalese majority.1 Despite the ethnic tensions, the various subject peoples of the Crown could see an advantage in allying to end colonial rule, though Tamils felt that the future division of power should be 50:50 between the Sinhalese and the various minorities. The Ceylon National Congress was formed after the Great War; it was made up of all the main communities, although the Tamils were later to break away.

The British introduced a universal franchise in 1931 (including women) and, following the Indian model, rapid moves were made towards self-governance. The Sinhalese often accused the British of divide and rule by favouring the Tamil minority, especially in the civil service. Nevertheless, both sides, along with other minorities such as the Muslims, often worked together towards the goal of political independence. Many on both sides agitated for the equal use of both vernacular languages, Tamil and Sinhala, to replace English as the dominant medium of government, courts and higher education. The indigenous languages with their distinct alphabets were mutually unintelligible, although more Tamils tended to speak Sinhalese (and English) as well as their own tongue, not least for commercial reasons.

When Japan made rapid military advances in the Second World War, and as India itself looked increasingly vulnerable, Ceylon’s strategic position made it ‘the Clapham Junction of the Indian Ocean’; it became the location of Lord Louis Mountbatten’s South-East Asia Theatre Command. Trincomalee was a vital naval sanctuary, even though it was bombed by the Japanese. The wartime demand for rubber and the presence of so many Allied service personnel helped to boost the local economy. The military also waged an incessant campaign to eradicate malaria. As part of their anglicization process, the British left a lasting legacy of loyalty to good secondary schools. The Spartan standards of the English public schools were faithfully reproduced. When a new British headmaster turned up at Trinity College, Kandy, he found 1,000 boys waiting to be caned as an opening duty. Well into the twenty-first century the ruling elites in the Sinhalese community formed classic school-based ‘old-boy’ networks within the political parties, the bureaucracy and especially the armed forces. They practised, for life, their own form of omerta.

As the war-weary British scuttled from the Raj, and looked on almost helplessly at the blood-soaked partition of the former jewel of Empire into India and Pakistan, the Ceylonese achieved their own national freedom in 1948. Soon after independence the leaders of the indigenous Tamils colluded with the Sinhalese-dominated government to send ‘home’ to India around half-a-million Tamils, many of whom had been in Sri Lanka for a generation or more. The Buddhist Sinhalese constituted perhaps 70 per cent of the population; the Hindu Tamils (both local and remnants of those more recently arrived from India) made up perhaps 20 plus per cent. Muslims were small in number but influential; they came from as far as Malaya or Indonesia or were descendants of much earlier Arab traders. Many spoke Tamil. In addition the population comprised mixed-race descendants of the Christian Dutch and Portuguese, sometimes called Burghers. Portuguese names proliferate in the modern Sri Lankan society; the legacy is particularly noticeable at graduation ceremonies. Many other smaller communities had thrived, not least the British settlers, as well as Jews and small groups of distinct African communities, who had arrived as slaves, first of the Portuguese.

At independence Sri Lanka was a Rubik’s Cube of religion, race and languages, though caste was also a rigid social denominator. Regional identities were also significant – elites emerged in Colombo and Kandy for example, frequently based on class and education (often at British universities) as well as historical or even royal lineages. Then party-political cleavages were added to the mix. Ceylon escaped the massacres of the independence of the Raj; ethnic tragedies were merely delayed, however.

The first years of independence

The first prime minister of independent Ceylon, D. S. Senanayake, a former agriculture minister in the colonial days, was keen to develop and improve on the celebrated irrigation systems of the independent kingdoms. This was related to his overall Sinhalese nationalist agenda, another part of which was to prevent the ‘New Tamil’ plantation workers voting for Tamil parties which could oppose his United National Party (UNP). The prime minister urged his Indian counterpart, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, to accept them as Indian nationals who should return home.

Sri Lankan politics has tended to be dynastic. Senanayake senior was replaced – briefly – by his son, Dudley; and then a former general took over the ruling UNP. S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike’s Freedom Party displaced the UNP. Bandaranaike championed the language issue – that Sinhala alone should replace English. Many in the new leadership had been educated at Oxbridge but now nationalism demanded not pin-striped suits but white cloth draped from the waist with a loose long-sleeved white shirt. This was Sri Lanka’s version of Chairman Mao’s buttoned-up tunic. In 1956 Bandaranaike’s ‘Sinhala Only Act’ prompted Tamil riots. This Act was a catalyst of the war that was to come.

Ethnic rioting and a rapid decline in economic conditions after the nationalization of key industries, such as transport and ports, created a crisis of confidence. Tamils living in Colombo and other areas were driven out and sought refuge in ancestral lands in the north and east. Many Sinhalese moved south. This was the beginning of what later became known as ‘ethnic cleansing’. Bandaranaike tried to end the chaos by offering to do a deal with the Tamils. A Buddhist monk took exception to this: he walked up to the prime minster and emptied a revolver into him at point-blank range. This set a pattern for a long series of political assassinations by all sides in the Sri Lankan imbroglio.

After a brief caretaker government, the dynastic ping-pong continued. Dudley Senanayake came back for three months. Then Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the assassinated prime minister’s widow, won power on a wave of sympathy, re-confirming the tradition of family rule. Not only was she the world’s first female premier, but she did not even hold a seat in parliament (she soon secured one in the Senate). While politicians swapped seats on the gravy train, ethnic tensions continued to simmer. Mrs Bandaranaike ensured that half-a-million ‘New Tamils’ were deported to India, with 300,000 allowed to stay. While her gender milestone played well as a beacon of the international non-aligned movement, her domestic record was poor. Some members of the armed forces and police plotted to step in to sort out the political mess, a common international fashion of the 1960s. The plot failed but it was to have a long-lasting impact on the relationship between the military and politicians.

The failed coup

In 1961, in the Tamil-dominated areas, the Mahatma Gandhi-influenced saryagraha movement had grown. This was non-violent opposition to the government’s language policy. Army units were stationed in Jaffna and, under the Public Security Act, a state of emergency was declared. A number of Tamil leaders were arrested under the emergency regulations. Even after the Tamil non-violent agitation abated, the state of emergency was maintained. One advantage to the government was that the volunteer elements of the armed forces could legally remain mobilized and thus be utilized against not only ethnic Tamil disturbances but also trade union-led strikes. In November 1961 port workers struck in Colombo. Other industrial action followed and trade union leaders called for a national general strike in January 1962. The armed forces and police made contingencies to maintain essential services. Leftist leaders suggested that the government was about to install military rule. Extra media censorship was introduced.

The military conspiracy must be understood in the paranoia of the time. A coup was indeed planned for 27 January 1962. The reasons for the conspiracy – a small but well-planned one – were varied. Some of the middle-ranking police and military men considered Mrs Bandaranaike unfit to rule, especially in a country which was too left-leaning (for them) and threatened by strikes and ethnic disturbances. It was to be a very British coup in many ways, in that a ‘gentlemanly’ code of behaviour was stressed, although the model suggested at the time was the military coup in Pakistan in 1958.

The Sri Lankan coup has been variously defined: firstly as a ‘Buddhist’ coup, because ‘not a drop of blood was to be shed’. It could be more accurately defined as a ‘Christian coup’ because the overwhelming number of people eventually charged were Protestants and Catholics drawn from the Sinhalese, Tamil and Burgher communities. Only three were Buddhists. The officer corps was dominated by Christians with large minorities of Tamils and Burghers. Mrs Bandaranaike had rapidly promoted Sinhalese officers. The Christian elite, which had dominated under British rule, felt that its position was being eroded; religion more than race played a role in the conspiracy. Nevertheless, the ‘Colonels’ coup’ is also an apt description because many of the conspirators were of colonel or lieutenant colonel rank or equivalent. None of the three service chiefs or the head of police was involved. It would be misleading to over-emphasize the religious element because other factors, including concern about the left-wing nature of the government, were at play.

The putsch was intended to be bloodless, swift and precise. Codenamed Operation HOLDFAST, the plan was to seize strategic positions in and around Colombo, capture the Radio Ceylon building (there was no television then), detain senior politicians and especially the prime minister, and to get her to announce a ‘voluntary’ transfer of power. (In many ways, albeit on an inevitably smaller scale, this coup attempt prefigured the successful army-police coup against the democratically elected Maldivian president, Mohamed Nasheed, in February 2012.)

The first part of Operation HOLDFAST was the establishment of a military dictatorship. The second phase was ‘indirect democracy’ where a council of ex-prime minsters would assist the governor-general in ruling the country. The third phase was a parliamentary election based on a new constitution guaranteeing equality to all races and religions. In short, some of the coup planners were trying to pre-empt a Sinhalese-Buddhist oligarchic regime. Great attention was paid to good treatment of those to be arrested. The plotters fretted about no harm coming to Mrs Bandaranaike and her son and two ‘beautiful’ daughters. The Bandaranaikes were to be sent off to comfortable exile in England, and the plotters had even spent time worrying about how the eldest daughter could gain access to Oxford. Some of the passwords prepared for the plot smacked of an Ealing comedy (for example, ‘Dowbiggin’, named after the ‘father of British colonial police’).

It was n...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Abbreviations

- Brief Timeline

- Introduction - Why the Sri Lankan War is Important

- Chapter 1 - The Background to the War

- Chapter 2 - The Rise of the Tigers

- Chapter 3 - Outbreak of the War

- Chapter 4 - Eelam War I (1983 – 87)

- Chapter 5 - Big Brother Steps In: The Indian ‘Peacekeepers’

- Chapter 6 - Eelam War II (1990 – 95)

- Chapter 7 - Eelam War III (1995 – 2002)

- Chapter 8 - The Long Ceasefire

- THE MAIN COMBATANTS

- THE CLIMAX

- AFTER THE SHOOTING WAR

- Select Bibliography

- Notes

- Index