eBook - ePub

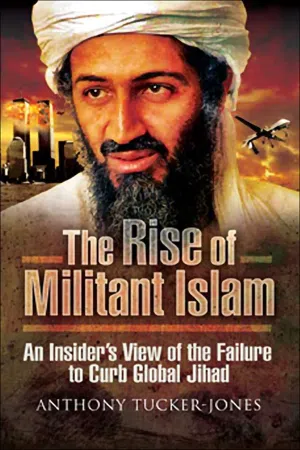

The Rise of Militant Islam

An Insider's View of the Failure to Curb Global Jihad

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise of Militant Islam

An Insider's View of the Failure to Curb Global Jihad

About this book

A former British Ministry of Defence staff member examines the mistakes made by Western intelligence in evaluating the threat of militant Islam.

At the end of the Cold War, the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction replaced the Soviet Union as the new enemy of world peace. The significance of militant Islam's growing disgust with Western foreign policy and apparent indifference to the suffering of Muslims worldwide was missed until it was too late.

In The Rise of Militant Islam, Anthony Tucker-Jones examines from an insider's perspective how Western intelligence misinterpreted every landmark event on the road to 9/11 and ultimately failed to curb global jihad.

The author, who served in the Defence Intelligence Staff, the British Ministry of Defence's top intelligence assessment organisation, gained an unparalleled insider's view of the growing war on terror and how the West's intelligence agencies were wrong-footed at almost every turn.

He traces the rise of international terrorism and its networks throughout the Muslim world, in Afghanistan, the Balkans, Algeria, Chechnya, Somalia and across the Middle East and uncovers the connections between them. He shows how the key to the growth of Al-Quaeda as a global terrorist organisation was not only the emergence of Osama bin Laden, but also the growing understanding of asymmetrical warfare, which the CIA had taught anti-Soviet jihadists in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Praise for The Rise of Militant Islam

"A highly detailed and thought-provoking book which chronicles the Western powers campaigns against the threat of militant Islam. This is a very detailed and well written book which does not demonize or idolize the Islamic terrorist and is not slow to criticize Western policy." —History of War

"This book explains very eloquently how the West ended up needlessly fighting a two-front war at the beginning of the millennia and how we could have avoided it if only we had exercised greater foresight and heeded the growing warning signs that Al-Qaeda and its leader meant business. . . . What sets The Rise of Militant Islam apart is the breadth and scope of the analysis and its central concept. . . . Highly recommended." —Nick Harvey, MP, Liberal Democrat Minister of State for the Armed Forces

At the end of the Cold War, the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction replaced the Soviet Union as the new enemy of world peace. The significance of militant Islam's growing disgust with Western foreign policy and apparent indifference to the suffering of Muslims worldwide was missed until it was too late.

In The Rise of Militant Islam, Anthony Tucker-Jones examines from an insider's perspective how Western intelligence misinterpreted every landmark event on the road to 9/11 and ultimately failed to curb global jihad.

The author, who served in the Defence Intelligence Staff, the British Ministry of Defence's top intelligence assessment organisation, gained an unparalleled insider's view of the growing war on terror and how the West's intelligence agencies were wrong-footed at almost every turn.

He traces the rise of international terrorism and its networks throughout the Muslim world, in Afghanistan, the Balkans, Algeria, Chechnya, Somalia and across the Middle East and uncovers the connections between them. He shows how the key to the growth of Al-Quaeda as a global terrorist organisation was not only the emergence of Osama bin Laden, but also the growing understanding of asymmetrical warfare, which the CIA had taught anti-Soviet jihadists in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Praise for The Rise of Militant Islam

"A highly detailed and thought-provoking book which chronicles the Western powers campaigns against the threat of militant Islam. This is a very detailed and well written book which does not demonize or idolize the Islamic terrorist and is not slow to criticize Western policy." —History of War

"This book explains very eloquently how the West ended up needlessly fighting a two-front war at the beginning of the millennia and how we could have avoided it if only we had exercised greater foresight and heeded the growing warning signs that Al-Qaeda and its leader meant business. . . . What sets The Rise of Militant Islam apart is the breadth and scope of the analysis and its central concept. . . . Highly recommended." —Nick Harvey, MP, Liberal Democrat Minister of State for the Armed Forces

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rise of Militant Islam by Anthony Tucker-Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Killing bin Laden

The world watched in horror and dismay on the morning of 11 September 2001 as Islamic terrorists slammed two airliners into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center (WTC), one into the Pentagon and a fourth into rural Pennsylvania en route to who knows where. On that fateful day the first aircraft struck the WTC north tower at 8.47 a.m., the second smashed into the south tower sixteen minutes later. By 10.30 a.m. both towers had collapsed into a mass of shattered glass, concrete and steel. Manhattan disappeared under a pall of choking smoke and dust centred on what became known as ‘ground zero’: a term normally associated with the impact of a nuclear warhead.1 New Yorkers staggered about their city in a daze of incomprehension and terror.

Less than an hour after the first New York attack, just outside Washington, the third hijacked aircraft flew into the south-west side of the Pentagon at 9.38 a.m. The attack was so precise many initially thought the building had been hit by a missile. About twenty-five minutes later the fourth aircraft came down in Pennsylvania after passengers unsuccessfully sought to regain control of the aircraft.

Initially, al-Qaeda had planned to hijack a total of ten planes, with the intention of crashing them into targets on both coasts of America. These would have included nuclear power plants and tall buildings in California and Washington State. However, the four planes had the desired effect. Internationally, the fear and disgust was palpable and the spectre of such outrages was to haunt every major city around the world for the next decade. America asked itself what it had done to inspire such hatred by militant members of Islam? But behind the scenes, the US government had been expecting such a spectacular attack for almost ten years. Osama bin Laden, leader of al-Qaeda, immediately named as Washington’s prime suspect, later said:

We calculated in advance the number of casualties from the enemy, who would be killed based on the position of the tower. We calculated that the floors that would be hit would be three or four floors. I was the most optimistic of them all …2

With these words he became America’s public enemy number one. What most Americans did not realise was that Washington had spent the last four years trying to kill him.

The international community immediately rallied to America. The very next day United Nation’s Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1368 and General Assembly Resolution 56/1 called for immediate international co-operation to bring the perpetrators to justice. They also called for much broader co-operation against global terrorism in general and this was followed on 28 September 2001 by UNSCR 1373. Enacted under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, it required every member state to undertake seventeen measures against all those who support – directly or indirectly – acts of terrorism.

Also on 12 September, President George W. Bush declared the attacks on the American homeland acts of war and requested Congress provide the resources – to the tune of $20 billion – to fight the terrorists wherever they might be. In the event, Congress doubled this sum. The following day, US Secretary of State, Colin Powell, confirmed that Osama bin Laden, believed to be hiding in Afghanistan, was a suspect.3

After British prime minister, Tony Blair, held a meeting with President Bush at the White House on 20 September, Operation Enduring Freedom was born. From the first news of the attacks, Blair was convinced it was the work of al-Qaeda and his immediate response was to offer support to America. Britain’s intelligence chiefs, notably the head of the Security Service, Secret Intelligence Service and the Government Communications Headquarters, also flew to Washington for urgent talks with their counterparts.4 The UK had a good handle on Islamic militant groups because it had tolerated fundraising offices in London.

British intelligence advised that bin Laden was the only one capable of such an attack and that no rogue states were involved. Blair was of the view that simply removing bin Laden from the picture would not be enough – and he was right, as militant Islam was already well established around the world. To some, the spread of Saudi Wahhabism, which preaches a return to the pure and orthodox practice of the ‘fundamentals’ of Islam, is seen as a threat to more moderate Muslim beliefs. Blair wanted a long-term strategy for dealing with Islamic fundamentalism – or rather, Islamic militancy. Bush told Blair that the focus would be Osama bin Laden and Afghanistan’s Taliban government. Washington demanded that the Taliban hand over bin Laden immediately. For the very first time the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) invoked its mutual defence clause on 2 October 2001, whereby an attack on a member state is considered an attack on all. Five days later the American-and British-led Coalition began systematic air attacks on the Taliban.

The American people – initially stunned and shocked by the sheer magnitude of this assault on their homeland – quickly recovered and sought to lash out as swiftly as possible at those it held responsible. In early October 2001 the Americans tried to kill Osama bin Laden, his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (architect of 9/11) and Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban. The al-Qaeda and Taliban hit list was much longer than this, but they were the ones that really mattered and the intelligence community naively hoped that by decapitating al-Qaeda the threat would somehow fade away. Tragically, this was a case of too little too late: 9/11 was, in fact, the culmination of a decade of steadily spreading militant Islam. Memories were short; for few beyond the intelligence and law enforcement circles remembered Ramzi Yousef’s dramatic truck-bomb attack on the WTC on 26 February 1993, which had first heralded the transnational Jihad against the United States.5 His attack predated bin Laden’s declaration of war on the American homeland by three and a half years. In that time militant Islam’s rise had gone unchecked.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the world’s intelligence agencies were asked: who or what is Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda organisation? What had motivated his followers to sacrifice themselves and carry out such appalling atrocities? It was clear that the perpetrators saw themselves at war with America, but to what end? What was particularly worrying was that many of the young men now attracted to Islamic militancy were well educated, often to university level. These were not stereotypical disenchanted youths from poverty-stricken backgrounds who had nothing to lose, these were men who could understand, articulate and rationalise their cause and yet willingly die for it.

When the experts briefed the politicians the explanation was far from comforting. Bin Laden, they said, since the mid-1990s, saw himself as the self-appointed defender of oppressed Muslims around the world, leading a coalition called the ‘International Islamic Front for Jihad Against the Jews and Crusaders to fight the US’. His battle cry was that the Christian Crusaders led by America were regularly being allowed to defile Islam. He and other Islamists were not so much advocates of a Pan-Arabic world but a Pan-Islamic one – or, more precisely, a Sunni-dominated Muslim world. Bin Laden dreamed of recreating the Islamic caliphate that followed the death of the revered Prophet Muhammad.

Osama bin Laden had clearly articulated his philosophy in the 1990s, calling for the imposition of Shariah law throughout the Arabian Peninsula, holy war against America, for supporting Israel and its occupation of Palestine, and the US military presence in Saudi Arabia (which, by his own admission, would not stop even if American troops were withdrawn).

His aim was to fight injustice perpetrated against Muslims anywhere in the world. In effect, he had tapped into every major Muslim grievance stretching from Europe to the Far East. Militant Islam was the new Marxism or socialism – at war with decadent Western capitalism. To some young Muslims, their faith in this creed was unshakeable.

Islamists believe that Islam is a political ideology, arguing that political sovereignty belongs to Allah and that Shariah or Islamic law should be state law – hence Islamism. To them, there can be no place for secular governments. Ultimately, this is what Jihadists or Holy warriors are fighting for, as most Islamists believe their goals can only be achieved through violence. However, militant Islam should not be viewed as a single problem, rather a series of interconnected ones, ranging from diverse international and regional political disenchantment to local, student-driven radicalism. Nor is Islam synonymous with Islamism, such a contention would be clearly ridiculous: fortunately, the global voice of the Islamists is in the minority, but in the wake of 9/11, militant Islam was in the ascendancy.

The true impact of ‘Franchise Terrorism’ had not yet been fully appreciated. The fact that al-Qaeda was, until 9/11, a bit player among many unsavoury militant Islamic groups in Afghanistan, was largely ignored by the Western intelligence agencies. A whole raft of terror groups were training in Afghanistan, which read like an international Who’s Who: the Kashmiri separatists, Harakat ul-Mujahidin, Jaish-e-Mohammed, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Tajik stragglers from the United Tajik Organisation, as well as other Uiguher and Chechen separatist organisations. Although Western intelligence was not really interested in any of them, they regularly caused mayhem on the Indian sub-continent and in Central Asia. The only ones that mattered to Operation Enduring Freedom were al-Qaeda, al-Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and the Taliban. They, after all, were held responsible for 9/11.

At the time, the question everyone was asking was: where is bin Laden hiding? Kandahar, the Taliban heartland or Jalalabad, were the two most likely locations. If bin Laden was going to run for the Pakistani border and Pakistan’s lawless North West Frontier Province, the latter city seemed the most likely. Also, because he and his supporters had now brought a rain of fire down on the Taliban, it seemed likely that he would be unpopular in Kandahar. The worry was that, from Jalalabad, he could easily lose himself in the vastness of the Hindu Kush Mountains.

The chance of finding bin Laden in a vast lawless haystack like Afghanistan seemed remote. The British Joint Intelligence Committee had assessed that he was still in Afghanistan, but exactly where remained open to informed guesswork. The previous three years had been a litany of lost opportunities when it came to killing the world’s most notorious terrorist leader. All in all, it was not an auspicious start.

The fact that, within the first twenty-four hours of the air campaign against the Taliban on 7 October 2001 few, if any, high value targets remained, mattered little. In reality, close air support for the advancing Tajik-dominated Northern Alliance proved more productive than bombing the Taliban’s ramshackle infrastructure. Those assigned to support Operation Veritas (as the UK’s part in America’s Operation Enduring Freedom was dubbed) had no expertise in counter-terrorism or Afghanistan. The representatives of the armed forces talked in terms of applied pressure and critical nodes, blind to the fact that Afghanistan had never functioned as a unitary state or had any real infrastructure. Without troops on the ground it seemed probable that the Taliban would simply shrug off the bombing.

A few days later an American kill was indeed confirmed: it was an important one but not the one everyone was hoping for. Perhaps, in Washington’s eyes, he was a good second best – the Egyptian Mohammed Atef, bin Laden’s operations chief and mastermind behind 9/11. A missile strike, probably directed by US Special Forces on the ground, killed him just outside Kabul. Two other senior Egyptian al-Qaeda leaders were also listed dead: Tariq Anwar al-Sayyid Ahmad and Mohammad Saleh. Another, Anas al-Liby, was rumoured killed, but it later emerged that he had escaped: he was eventually captured in Afghanistan the following year.6

As the US-led air campaign gathered pace, several more senior terrorists were claimed, including, it was rumoured, Juma Namangani, leader of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. His forces were openly fighting alongside the Taliban and al-Qaeda against the Northern Alliance. No one in the West cared about his demise but in Russia, Tajikistan, China and Chechnya, it was a different matter. Fighters from the last three countries were among his ranks. Similarly, a senior member of Lashkar-e-Tayyiba was reported killed – good news for the Indian government – but Osama bin Laden easily eluded America’s military might.

Few people in the outside world realised that this was not the first attempt on bin Laden’s life. America had been attempting to eliminate him since the 1990s. Saudi nationals using assault rifles tried to assassinate him in the Sudanese capital Khartoum in 1994. Before 9/11 it was President Bill Clinton who signed a memorandum instructing the CIA to work with local elements in Afghanistan to capture bin Laden and authorised them to use alternative methods with which to attack al-Qaeda.

To this end, in the mid-1990s, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) established an Osama bin Laden Task Force to attempt an assassination using poison. Trying to find bin Laden in the vast wastes of the Afghan mountains proved time-consuming and exhausting for those Special Forces and local agents assigned to the hunt. The CIA even attempted to snatch bin Laden from Afghanistan in 1997, but the mission was to be aborted for diplomatic reasons.7 Bin Laden was not yet aware that he was under intense CIA scrutiny, or indeed that the National Security Agency8 was eavesdropping on his mobile phone. This meant that, while he was at Tarnak Farms he stuck to a fairly predictable schedule.

George Tenet, the CIA’s Director, was never keen on the kidnap plan. The idea was that Pashtun tribesmen would grab bin Laden and hide him in a cave until US Special Forces could retrieve him. Much could go wrong with such a mission and Tenet firmly believed that Clinton only authorised bin Laden’s capture not his death. To the CIA, ambiguity hung over the directive to use lethal force to apprehend bin Laden.

After 9/11, senior Clinton officials vigorously disputed Tenet’s contention that he had never been authorised to kill bin Laden. Similarly, it was only after 9/11 that President Clinton confirmed that he had authorised the arrest and, if necessary, the killing of Osama bin Laden, and that America had made contact with a group in Afghanistan to do it. He also admitted that, in the late 1990s, America trained Pakistani commandos for a bin Laden snatch-and-grab raid, but lacked the necessary intelligence to carry it out.

Significantly, the plan to kidnap bin Laden was pre-empted by Tenet’s visit to Saudi Arabia to solicit Saudi assistance in dealing with bin Laden. Crown Prince Abdullah said yes, the Saudis would buy off the Taliban to hand him over. However, Washington was instructed to keep the deal secret and bin Laden would not be sent to the US to face trial.9 Sandy Berger, US National Security Advisor, was informed, and as this seemed a much easier solution to the bin Laden problem, the CIA kidnap plan was cancelled. After Tenet’s meeting in Saudi Arabia, Prince Turki held talks with the Taliban in Afghanistan but these came to nothing. Some felt that the kidnap plan was a lost opportunity and that the Saudi offer permitted Tenet to weasel out of covert action against bin Laden.

After the bombing of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, Michael Scheuer, chief of the bin Laden tracking unit, received a visit from Tenet. T...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Preface

- Timeline

- 1. Killing bin Laden

- 2. Goodbye Afghanistan

- 3. The Mountains of Allah

- 4. Seekers of the Truth

- 5. Somalia: a Lesson in Victory

- 6. Yemen: a Nest of Vipers

- 7. Bosnia: Trouble with ‘Ragheads’

- 8. Algeria: Sacred Frustration

- 9. Chechnya: Moscow’s Running Sore

- 10. Kosovo: a Missed Opportunity

- 11. Lebanon: Cradle of Terror

- 12. The Mahdi and the Pharaohs

- 13. Middle East Sojourn: Saudi Arabia

- 14. East Africa: War is Finally Declared

- 15. Punishing the Taliban

- 16. Tora Bora: Afghanistan Revisited

- 17. Saddam’s Terrorists

- 18. Unwelcome Aftermath: International Jihad

- 19. Where’s bin Laden?

- 20. Syria: on the Brink

- 21. Iraq: the New Breeding Ground

- 22. Holy Terror: the Rage of Islam

- Epilogue

- Glossary of Militant Islamic Groups

- Notes and References

- Bibliography