- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

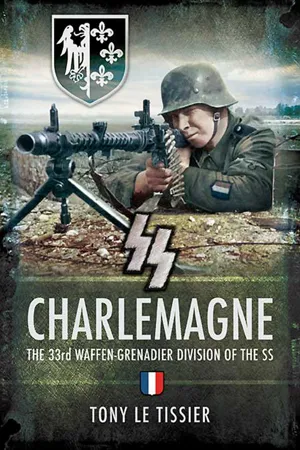

In May 1945, as the triumphant Red Army crushed the last pockets of German resistance in central Berlin, French soldiers fought back. They were the last surviving members of SS Charlemagne, the Waffen SS division made up of French volunteers. They were among the final defenders of the city and of Hitlers bunker. Their extraordinary story gives a compelling insight into the dreadful climax of the Battle for Berlin and into the conflicts of loyalty faced by the French in the Second World War. Yet, whatever their motivation, the performance of these soldiers as they confronted the Soviet onslaught was unwavering, and their fate after the German defeat was grim. Once captured, they were shot out of hand by their French compatriots or imprisoned. SS Charlemagne is a gripping, fluently written study of one of the most revealing side stories of the war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access SS Charlemagne by Tony Le Tissier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia militare e marittima. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Formation

The crushing military defeat of France in 1940 arose out of many factors, but principally out of the devastating results of the First World War of 1914–1918, from which the country had yet to recover. The country’s faith in the defences of the Maginot Line had been shattered when the German blitzkrieg smashed through between the French mobile forces covering the still open northern flank and the Maginot Line itself. Poor military leadership and lack of political willpower led to a swift disintegration of the state and humiliating surrender.

Following the signing of the armistice at Compiègne on the 22 June 1940, the new French government, headed by Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain with Pierre Laval as Deputy Premier, settled in the town of Vichy. France was now divided into occupied and unoccupied zones, but the coastal and border areas became restricted zones, while the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine were absorbed into the Third Reich, coming under the German conscription laws, as did the Duchy of Luxembourg, and the conscripts from these areas were deliberately deployed away from their home territory.

With the population stunned by the crushing defeat of French arms and the German invasion, Pétain and Laval sought to set aside the political turmoil of the inter-war years under the Third Republic by reviving morale with what they dubbed a National Revolution devoted to ‘Work, Family and Country’.

On 11 October 1940, Pétain broadcast a speech to the nation in which he alluded to the possibility of France and Germany working together once peace had been established in Europe, using the word ‘collaboration’ in this context. In any case, with 1,700,000 French servicemen in German prisoner-of-war camps, his government had little alternative but to comply.

The Germans, on the other hand, were out to avenge their own humiliation at Versailles at the end of the previous war, and had no real interest in establishing a sympathetic ally or even an independent fascist state in France. In its relationship with France, all other concerns were subordinate to German interests.

A plethora of collaborationist political movements arose in the Paris area. The principal parties concerned were the Mouvement Social Révolutionaire (MSR), founded by Eugène Deloncle, Marcel Bucard’s Parti Franciste, the Parti Populaire Français (PPF), founded in 1936 by Jacques Doriot, and the Rassemblement National Populaire (RNP), founded in February 1941 and led by Marcel Déat and Eugène Deloncle.

On 22 June 1941, the day that Adolf Hitler began his attack on the Soviet Union, Jacques Doriot launched the idea of forming a legion of French volunteers to fight Bolshevism alongside the German Army. The Germans were not particularly enthusiastic about allowing the French to participate, but eventually approval was given on 5 July 1941 for the formation of the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF), limiting the effective strength to 100,000 men. It was to be recruited from men aged 18 to 45, born of Aryan parents and in good health.

Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain’s Vichy Government supported this initiative, sending a telegram with his best wishes to the head of the LVF, and the Prefects of Departments also gave their support. Despite an impressive press campaign, only 1,600 volunteers came forward, out of which only 800 passed the strict German medical examinations, and were assembled at Versailles, where they held the first parade at the Borguis-Desbordes Barracks on 27 August 1941. The reasons for volunteering were mainly ideological, out of catholic or political conviction, but also because of the attractively high rates of pay and allowances. Between July 1941 and June 1944, some 13,000 volunteers were to apply, but only about half of these passed the rigorous German medical examinations.

Doriot left in September 1941 as an NCO with the first contingent of volunteers for Deba in Poland, where the recruits were equipped with German uniforms bearing a tricolour sleeve badge, and mustered into the Wehrmacht’s Infanterie-Regiment 638 under the command of 65-year-old Colonel Roger Henri Labonne (1881–1966), a former officer of French colonial troops. They were also required to swear an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler as commander-in-chief. Both the uniform and the oath came as a shock to the volunteers, who had been expecting to wear French uniforms and saw no reason for swearing the oath to a foreign commander-in-chief, but these obstacles were quickly overcome with the enthusiastic aid of their padre, the Roman Catholic, national socialist enthusiast, Monsignor de Mayol de Lupé. They would, however, be allowed to wear French uniforms when on leave in France.

The regiment consisting of two battalions, the 1st under Captain Leclercq, later Major de Planard, the 2nd under Major Girardeau, then left Deba at the end of October and reached Smolensk on 6 November 1941. No better equipped for the severity of the Russian winter than the rest of the German Army at that time, the troops then marched towards Moscow in blizzards and icy rain, their heavy equipment following them in horse-driven wagons. By the time they reached the front, only 63km from Moscow, a third of the men were suffering from dysentery and the regiment had lost 400 from sickness or straggling. The regiment was then assigned to the 7th Infantry Division and the regimental headquarters established in Golovkovo.

On 1 December, with the temperature down to -40 °C, the 1st Battalion was ordered to attack elements of the 32nd Siberian Division in a snowstorm. Within a week the 1st Battalion was so depleted that it had to be replaced by the 2nd Battalion. By 9 December, when the regiment was taken out of the line, it had suffered 65 killed, 120 wounded and over 300 cases of frostbite. Lieutenant-Colonel Reichet, the divisional chief-of-staff reported: ‘The men are keen enough, but lack military training. The NCOs are quite good, but cannot do much because of their inefficient superiors. The officers are incapable and were only recruited on political criteria. The Legion is not fit for combat. Improvement can only be achieved by renewal of the officer corps and thorough military training.’

The regiment was then sent back to Poland, where 1,500 volunteers were dismissed and returned to France, together with most of the officers, including Colonel Labonne. A fresh batch of volunteers arrived to replenish the ranks and training continued with an emphasis on the NCO backbone. The remains of the two existing battalions were merged and a new second battalion formed from fresh volunteers arriving from France. Eventually the regiment was reorganised into 3 battalions of about 900 men each, which were then allocated separately to various security divisions to assist in anti-partisan operations behind the lines, where the German assessment of the LVF remained poor. In February 1944, the regiment was reunited and assigned to the 286th Security Division.

On 18 July 1942, the Vichy Government instituted La Légion Tricolore as an official French Army replacement for the LVF, but the Germans refused to accept this concept and after only six months its members were absorbed into the LVF.

In June 1943, Colonel Edgar Puaud (1889–1945), a former officer in the French Foreign Legion, was given command of the LVF. Marshal Pétain later promoted him to the rank of general in the French Army, and made him a Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur, but the Germans were not prepared to accept him in that rank, and he initially served with the rank of a Wehrmacht colonel.

Another 91 officers, 390 NCOs and 2,825 soldiers left for the Eastern Front in 1943, but incidents with the police involving LVF volunteers on leave did nothing to enhance their reputation. Militarily ineffective and supplied with recruits of dubious quality, the LVF remained a political and propaganda instrument of the collaborationist parties, despised by most Frenchmen, and considered suspect both politically and militarily by the Germans.

Consequent upon a new decree of 23 July 1943 enabling direct enlistment into the Waffen-SS, a new recruiting drive began in the Unoccupied Zone (Vichy France), attracting some 3,000 volunteers. This led to the formation of the Französische SS-Freiwilligen Grenadier Regiment (French SS-Volunteer Grenadier Regiment) the following month. Also known as the Brigade Frankreich or the Brigade d’Assault des Volontaires Français, it was placed under the command of the 18th SS-Panzer-Grenadier Division Horst Wessel in Galicia, where it suffered heavy casualties.

Parallel to the LVF, other Frenchmen were engaged in the German Army and Navy (Kriegsmarine), the NSKK (Nazi Party Transport Corps), whose units were gradually becoming armed, the Organisation Todt (OT) (Construction Corps), police and guard units. Individuals from these various organisations now began leaving to enlist in the Waffen-SS.

In fact, the creation of this first French SS unit signalled a deep change in the type of engagement. From then on the political aspirations of the collaborationist parties had little impact. It was no longer a question of fighting for the glory of France, but for Europe, primarily for a national-socialist German victory. As someone commented: ‘The French SS are in fact purely and simply German soldiers.’

On 27 August 1943, the second anniversary of the founding of the LVF, a battalion of the regiment paraded at Les Invalides in Paris, where General Bridoux, the Vichy Minister of War, presented the regiment with a new Colour. This Colour, which was of the regular French Army pattern, bore the legend ‘Honneur et Patrie’ and the battle honours ‘1941-1942 Djukowo’ and ‘1942-1943 Bérésina’. There was then a presentation of awards to wounded veterans, and a march past in their honour by the mounted Garde Républicaine. Led by a company in German uniform and carrying their Tricolore standard, the battalion then marched to Notre Dame for a celebration of mass before proceeding up the Avenue des Champs Elysées for a wreath-laying ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, cheered all the way by representatives of the many political parties supporting collaboration with the Germans.

The LVF was still an active force. As the German forces reeled back from the Soviet onslaught of 1944, Major Eugène Bridoux’s battalion was called upon to form a combat team to block the Moscow–Minsk road in front of Borrisov near the Beresina River. On 22 June, his battalion, along with police units and a handful of tanks, fought a delaying action until the following evening that cost it 41 dead and 24 wounded, but inflicted considerable damage to the Soviets, including the loss of some 40 tanks. It fought so well that the Soviet opponents reported being up against two divisions. Exhausted and starving, the survivors reached the LVF depot at Greifenberg two weeks later. Here all French servicemen within the German armed forces were being assembled.

In the spring of 1944 the German High Command (OKW) had issued a general order foreseeing the transfer of all foreign soldiers serving in the German armed forces to the Waffen-SS in order to simplify the situation and maintain the strength of the Waffen-SS, for which German citizens were exempt from conscription by law and could only volunteer. The French were some of the last to be affected by this order, both the LVF and the French SS-Storm Brigade still being actively engaged on the Eastern Front.

The creation of the Waffen-SS Charlemagne Brigade was decided in August 1944 when Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler gave the necessary orders for the LVF and the French SS-Storm Brigade to assemble during September at the Waffen-SS training area northeast of Konitz in the former Danzig Corridor. To these troops were added some 3,000–3,500 French volunteers from the German Navy, the latter coming via the LVF depot at Greifenberg in Pomerania, which was to become the Charlemagne Brigade depot. Individual transfers from Wehrmacht units were to continue to arrive right until the Charlemagne left for the front.

Once it had been assembled, the Brigade was moved to Wildflecken Camp in Franconia, 90km northeast of Frankfurt-am-Main and about 900m high in the Rhön massif, where the first companies detrained on 28 October, replacing elements of the SS-Wallonien and Hitler-Jugend Divisions.

Then, on 5 November, a reinforcement of 1,500 Miliciens arrived from France to be absorbed into the Brigade. They were not generally welcome. The Milice Français had been created by Premier Pierre Laval on 31 January 1943 as his own private police force, with Joseph Darnand as its Inspector General. Then on 2 June, the Franc Garde wing of the Milice was created for police and security tasks in the Unoccupied Zone under the command of Major Jean de Vaugelas, but remained unarmed until November, during which time several members were assassinated by members of the Resistance. Discussions with the SS led to an agreement whereby, in exchange for the provision of light weapons, the Milice would encourage enlistment in the Waffen-SS. Some 200 Miliciens then joined the Waffen-SS, including Henri Fenet, who was later to play a prominent role in the Charlemagne.

On 27 January 1944, the Milice was given permission to recruit in the Occupied Zone, and Jean Bassompierre and François Gaucher were recalled from the LVF on the Eastern Front to become inspectors in this organisation. The strength of the Milice rose in mid-1944 to 30,000, of which 10–12,000 were members of the Franc Garde active in the rounding up of Jews and assisting the German troops against the Resistance in what was virtually a civil war, gaining the Miliciens a reputation for assassination of political opponents, brutality and torture.

By August 1944, with Paris liberated and much of France under Allied control, the Milice and their families had to flee. Darnand led convoys of them, running the gauntlet to the relative security of Lorraine, where 6,000 Miliciens and 4,000 of their dependants gathered before moving on to Germany. Of these, 1,500 Miliciens opted to join the Charlemagne, while Darnand took most of the remainder to fight against the partisans in northern Italy. Those that did get through paid a heavy price: 76 were executed by firing squad in the Grand Bornand following a peremptory trial by their compatriots on 24 August. Consequently, the absorption of the Miliciens into the Charlemagne was not an easy matter, as we shall see.

The formation of the Charlemagne as a Waffen-SS unit was allocated to SS-Major-General Dr Gustav Krukenberg. Born on 8 March 1888 in Bonn, Krukenberg had ended the First World War as a young second-lieutenant attached to the General Headquarters at Spa with Kaiser Wilhelm II. Between the wars he lived more than five years in Paris, where he had formed several relationships in journalist and diplomatic circles, and came to understand the French mentality particularly well. From Paris he had moved to Berlin, where he worked as a legal adviser to an English firm in the chemical industry.

In 1939 Dr Krukenberg was mobilised in various headquarters in the rank of colonel of the reserve, his last position being with Wirtschaftstab Ost. He then spent time as chief-of-staff to the Vth SS-Mountain Corps in Yugoslavia. He was then transferred from the Army to the Waffen-SS as Inspector of SS Latvian formations and, after the invasion of Latvia by the Red Army in July 1944, he organised the defence of Dunaburg with these local forces with considerable success. On 24 September 1944, he was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Waffen-SS, and assigned as Inspector of SS French formations.

In a memorandum prepared by him in 1958, Krukenberg recalled his tasks:

a) Put into effect and supervise all the measures ordered by the OKW guaranteeing the incorporation of the volunteers from various elements of the Wehrmacht [LVF, OT, Navy, NSKK, etc.].

b) Control of the aptitude of members of the Brigade – old and new – of all ranks to their engagement at the front and in the performance of their methods of combat. [Krukenberg was used to sacking incompetent NCOs and soldiers and in making the necessary demands in the case of officers.]

c) Examining the equipment and armament of the Brigade, as well as the organisation of the supply services, which, as for the LVF, remained a German responsibility. [A quartermaster was appointed as a result of this inspection.]

d) Supervising the theoretical and practical instruction of former French Army officers and NCOs to ensure that their tactical training and military habits conformed to German conceptions.

e) Establishing a military training plan for the troops and surveillance of its execution, despatching officers and soldiers to courses at various German military schools of the various arms.

f) Initiating and maintaining all measures to psychologically prepare those members of the Brigade who had not previously experienced defensive ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- List of Maps

- Content

- List of Plates

- Preface

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Photo Section

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Annex A

- Annex B

- Bibliography

- Index

- Armed Forces Index