- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Polish Underground, 1939–1947

About this book

This study of the Polish resistance movement chronicles the operations of various factions from WWII through the postwar battle for power.

The Polish partisan army famously fought with tenacity against the Wehrmacht during World War II. Yet the wider story of the Polish underground movement, which opposed both the Nazi and Soviet occupying powers, has rarely been told. In this concise and authoritative study, historian David Williamson presents a major reassessment of the actions, impact and legacy of Polish resistance.

The Polish resistance movement sprang up after the German invasion of 1939. As the war progressed, it took many forms, including propaganda, spying, assassination, disruption, sabotage and guerrilla warfare. Many groups were involved, including isolated partisan bands, the Jewish resistance, and the Home Army which confronted the Germans in the disastrous Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

Going beyond the Second World War, Williamson's graphic account chronicles the clandestine civil war between the Communists and former members of the Home Army that continued until the Communist regime took power in 1947.

The Polish partisan army famously fought with tenacity against the Wehrmacht during World War II. Yet the wider story of the Polish underground movement, which opposed both the Nazi and Soviet occupying powers, has rarely been told. In this concise and authoritative study, historian David Williamson presents a major reassessment of the actions, impact and legacy of Polish resistance.

The Polish resistance movement sprang up after the German invasion of 1939. As the war progressed, it took many forms, including propaganda, spying, assassination, disruption, sabotage and guerrilla warfare. Many groups were involved, including isolated partisan bands, the Jewish resistance, and the Home Army which confronted the Germans in the disastrous Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

Going beyond the Second World War, Williamson's graphic account chronicles the clandestine civil war between the Communists and former members of the Home Army that continued until the Communist regime took power in 1947.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Polish Underground, 1939–1947 by David G. Williamson, Christopher Summerville in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

Maps and Plates | ||

Acknowledgements | ||

Background | ||

Poland: a Fragile State | ||

Planning Guerrilla Warfare | ||

Invasion and Partition | ||

Siege of Warsaw, 7–27 September 1939 | ||

Formation of the Polish Government-in-Exile | ||

‘Post-September’ Resistance | ||

Creation of the Polish Underground | ||

Enemy-Occupied Poland | ||

General Government | ||

German Army of Occupation | ||

Soviet Zone | ||

Poles and the Occupation | ||

Campaign Chronicle | ||

Resistance, September 1939–June 1940 | ||

Attempts to Centralize Armed Resistance and Avoidance of Premature Action | ||

Sabotage Operations in Romania and Hungary | ||

Organization, Supply and Sabotage in Poland | ||

Fall of France | ||

Impact of the Fall of France on the Polish Underground | ||

London and the Polish Resistance After the Fall of France | ||

Communications with Occupied Poland | ||

Plans for Future Action | ||

Polish Resistance Amongst the Diaspora | ||

Growth of Resistance in German-Occupied Poland | ||

Soviet-Occupied Poland | ||

Diplomatic Consequences of Barbarossa | ||

Conditions in Poland, June 1941–January 1943 | ||

Growing Popular Resistance | ||

Attempts to Supply the Underground by Air | ||

Diversionary Activities in Poland | ||

Operation Wachlarz | ||

Intelligence and Liaison, 1941–1942 | ||

Development of the Polish Home Army, June 1941–December 1942 | ||

British POWs and the Polish Resistance | ||

The Written Word as a Weapon | ||

The Spectre of Communism: Communist Partisan Bands, 1941–1942 | ||

The Zamość Crisis | ||

Polish Resistance in France | ||

Ambitious Diplomatic Schemes | ||

Deteriorating Relations Between the Polish Government-in-Exile and the USSR | ||

Katyń | ||

Anglo-American Appeasement of the USSR | ||

The State of Poland, January 1943–August 1944 | ||

The Streamlining of the Underground State | ||

Assassinations | ||

The Gestapo Fights Back | ||

Intelligence, 1943–1944 | ||

Aircraft and Ballistic Rocket Projects | ||

The Communist Challenge, 1943–1944 | ||

Jewish Resistance and the Poles | ||

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, April–May 1943 | ||

Resistance in the Other Ghettos | ||

Źegota and Polish Assistance to the Jews | ||

Partisan Operations: the AK | ||

Operation Tempest | ||

Supplying the AK from Italy | ||

Operations Jula and Ewa, April 1944 | ||

Partisan Operations: GL/AL and the ‘Forest People’ | ||

The Red Army Enters Polish Territory | ||

The Political Failure of Operation Tempest, January–July 1944 | ||

The SOE Intervenes, May 1944 | ||

Resistance Behind German Lines in the General Government, January–July 1944 | ||

The Red Army Crosses the Bug | ||

Polish Resistance in Europe | ||

The Warsaw Uprising: the Decision to Revolt | ||

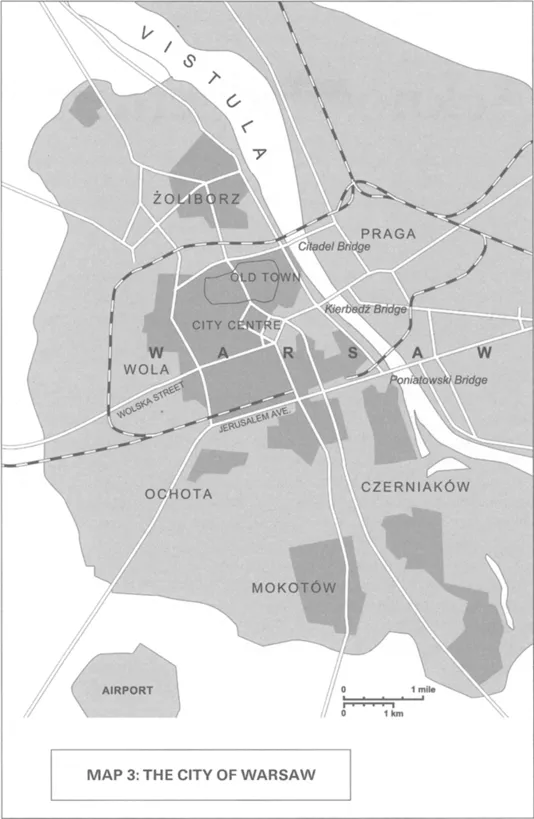

The Outbreak of the Revolt: 1–5 August | ||

The German Counter-Offensive | ||

The Attack on the Old Town, 8–19 August | ||

The Insurgents Retreat from the Old Town | ||

The City Centre, Mokotów and Zoliborz | ||

Attitude of the Soviet Union | ||

Help from the Western Allies: Too Little and Too Late | ||

September: Hanging on | ||

Surrender | ||

The Civilian Population During the Uprising | ||

The Three Polands, October 1944 | ||

Opposition to the Polish Committee of National Liberation | ||

The Re-establishment of the Underground State in the General Government | ||

The Moscow Conference, October 1944 | ||

The AK’s Attempt to Regroup, October 1944–January 1945 | ||

Supply and Liaison | ||

Dispatch of the British Military Mission to Poland | ||

Intelligence, Sabotage and Guerrilla War in the General Government, October 1944–January 1945 | ||

The AL and NSZ | ||

Soviet Advance, January 1945 | ||

Continuing the War Against Germany Outside Poland | ||

Aftermath | ||

Dissolution of the AK and the Emergence of NIE | ||

Flight and Concealment | ||

End of the Underground State, March–June 1945 | ||

The Revolt of April–July 1945 | ||

Creation of the Provisional Government of National Unity and the First Amnesty | ||

Support for the Underground from Poles Abroad | ||

General Anders and the Former Polish Government-in-Exile | ||

The Referendum and the General Election, 1946–1947 | ||

Assessment | ||

Appendices | ||

| I | Chronology of Major Events | |

| II | Biographies of Key Figures | |

| III | Glossary and Abbreviations | |

| IV | Orders of Battle and Statistics | |

| V | Survivors’ Reminiscences | |

Sources | ||

Index | ||

Maps and Plates

Maps

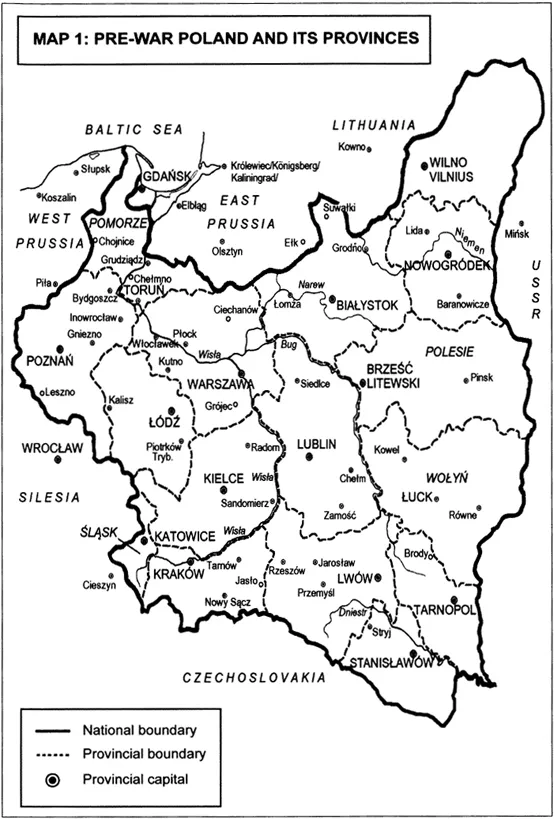

1. Pre-war Poland and its Provinces

2. Occupied Poland

3. The City of Warsaw

Plates

Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935).

Władysław Sikorski (1881–1943).

Kazimiersz Sosnkowski (1885–1969).

Michał Tadeusz Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski (1893–1964).

Stefan Starzyński (1893–1943?)

Witold Pilecki – veteran of Auschwitz and the Warsaw Uprising.

Executed by the Soviet NKVD in 1948.

Executed by the Soviet NKVD in 1948.

Henryk Dobrzański, alias ‘Hubal’ (1897–1940).

Franciszek Kleeberg (1888–1941).

Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski (1895–1966).

Stanisław Kopanski (1895–1976).

Władysław Rackiewicz (1885–1947).

Stefan Rowecki, alias ‘Grot’ (1895–1944)

Jan Karski (1914–2000).

Colin Gubbins (1896–1976).

Hans Michael Frank (1900–1946).

Arthur Seyss-Inquart (1892–1946).

Erich Julius Eberhard von dem Bach (1899–1972).

AK partisans.

Katyn massacre – exhumation of bodies 1943.

Two views of AK partisans.

Jewish partisan group active in the Nowogródek region.

Partisan Group ‘Zbeda’.

‘Edelman’ Partisans – Jewish fighters active in the Lublin region.

Warsaw Ghetto – civilians being marched off.

AK insurgents during the Warsaw Uprising.

Two views of AK insurgents during the Warsaw Uprising.

Two views of AK insurgents during the Warsaw Uprising.

AK insurgents during the Warsaw Uprising.

AK child-fighters, Warsaw 1944.

AK nurse, Warsaw 1944.

German troops deploy during the Warsaw Uprising.

Oskar Paul Dirlewanger (1895–1945).

German Stuka bombs Warsaw’s Old Town.

Warsaw in ruins after the Uprising.

Acknowledgements

Sincerest thanks are due to Jan Brodzki, Hanna Skrzyńska, Halina Serafinowicz and Maria Karczewska-Schejbal, who all found the time and patience to talk to me about their traumatic experiences in occupied Warsaw. At the Polish Underground Movement Study Trust in Ealing, I was treated with the greatest of consideration and offered invaluable advice and assistance.

Dr Suchitz at the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, as well as the staff at the National Archives and in the Reading Room of the Imperial War Museum were unfailingly helpful whenever I approached them. I would also like to thank Ewa Haren, who helped with Polish spellings and accents, and Sebastian Bojemski, who had much invaluable information to impart. Above all my thanks and gratitude are due to Christopher Summerville, my ever patient and highly perceptive editor, who has saved me from making many a careless error.

Thanks are also due to the copyright owners of the following papers, which are held in the Department of Documents in the Imperial War Museum, for granting me permission to quote in some cases quite extensively from them: S.H. Lloyd-Lyne, G. Manners, Z.R. Pomorski, R. Smorczewski and R.K. Stankiewicz.

Every effort has been made to trace and obtain permission from copyright holders of material quoted or illustrations reproduced.

Background

In December 1942 Lord Selborne (Minister for Economic Warfare with responsibility for special operations in German-occupied Europe) observed that the Poles alone, amongst the subjugated European nations, had the ‘glory’ of never producing a ‘Quisling’. This was partly because the Germans made no secret of their ultimate intention to eliminate Poland from the map of Europe and to condemn the Poles to perpetual slavery. There was, therefore, little room for political collaboration. But in Poland there was also a powerful and romantic tradition of revolt, which particularly inspired the intellectuals and officer class. For some 200 years, from the 16th to 18th century, Poland had been a great power but then, as a result of internal political instability, she had been partitioned between Austria, Russia and Prussia in 1795, and then again in 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The history of the various revolts and conspiracies (1794, 1830 and 1863) against the occupying powers was well known to every Polish school child. Collectively, these uprisings contributed to a heroic interpretation of the martyrdom of Poland – the Christ among nations – destined to rise again and liberate the European peoples from bondage.

In 1918 – with the simultaneous disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the defeat of Germany and paralysis of Russia caused by the Bolshevik revolution and subsequent civil war – the Polish state re-emerged. In the west, her frontiers were fixed by the Treaty of Versailles but in the east, due to the absence of Russia from the peace conference, there was no accepted settlement. It was only the defeat of the Red Army by Polish troops in September 1920 that led to the Treaty of Riga, which awarded Poland considerable territory in Byelorussia and the Ukraine. Poland was indeed resurrected but her very existence depended on the continuing weakness of her two great neighbours, Germany and the USSR. Once these states recovered their economic and military power, unless backed decisively by the Western powers, Poland faced the threat of yet another partition.

Poland: a Fragile State

The new Poland was essentially a fragile structure. It was largely a peasant state with only a small industrial base. It was divided ethnically and thus politically unstable. According to the census of 1931, the Poles composed only 69% of the population while, in the eastern territories, they were in a minority compared to the Ukrainians and Byelorussians. There were also 3 million Jews, many of whom were unassimilated.

Political crisis followed political crisis until Józef Piłsudski – the first Polish head of state and hero of the Polish–Russian war of 1919–1920 – seized power in the coup of May 1926. While he managed to stabilize the situation and build up Poland’s armed forces, the coup was deeply resented by the democratic parties. On his death in 1935, power passed to the Colonels, who increasingly ruled in a more authoritarian manner, and politics degenerated into a cycle of protest and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents