![]()

CHAPTER ONE

1939

Fear and Foreboding

It was early September. Hitler had followed up his reclamation of lands he judged as belonging to Germany and to the new Third Reich, and he had now followed this by invading states to which he had no claim at all. Invading Poland was an act of aggression, but also a first step in the expansion of his Reich towards that new German and Aryan empire he planned. The word ‘Aryan’ related to the supposed desired ‘racial purity’ as defined by the philosophy behind Nazism, fixed on the notion that there was a superior breed of humanity on earth – the Germanic tribes – and that other races were secondary, degenerate and in most cases deserving of extinction. When the German troops marched into Warsaw, few would have understood that twisted vision, but the jackboot instilled fear and apprehension in a world that had for years worked tirelessly to preserve peace. People came to realize that too many concessions had been made to Hitler, and that he had been both misunderstood and underrated.

There was going to be a repeat of 1914, people felt, with waves of refugees coming towards Yorkshire in need of help and support. Leeds was well-used to such situations: between the 1840s and 1900 the population of the city had grown from around 88,000 to 178,000 and many of these people were refugees from European political instability. One of them was Michael Marks: a refugee from Poland who was to start his Penny Bazaar in Leeds market; the future Marks and Spencer chain.

In Leeds, while the shadow of imminent war threatened, there was confidence in the massive, well-established industrial base of the city; something that would promise a huge resource when the call came to gather all energies and assets to take on the Fascist urge to dominate weaker nations and enlarge their power. In the first year of the twentieth century, Leeds had such sturdy, imperious firms embedded in the manufacturing mindset of the Victorians as John Atha, leather manufacturer of Hunslet; Verity’s, makers of special appliances for the building trade; the worsted and woollen manufacturers W.E. Yates of the Welllington Mills in Bramley and many more. There were saw mills, corn-mill engineers, dyers, tanners, cloth and stuff merchants, glass-makers and grease-makers. In addition there were many importers and traders, and in the clothing outfitters there was one of the principal resources of a nation soon to be at war. These were all obvious strengths and valuable assets but more valuable still were the children, the next generation, and these had to be considered now that bombing of towns and cities was a distinct possibility.

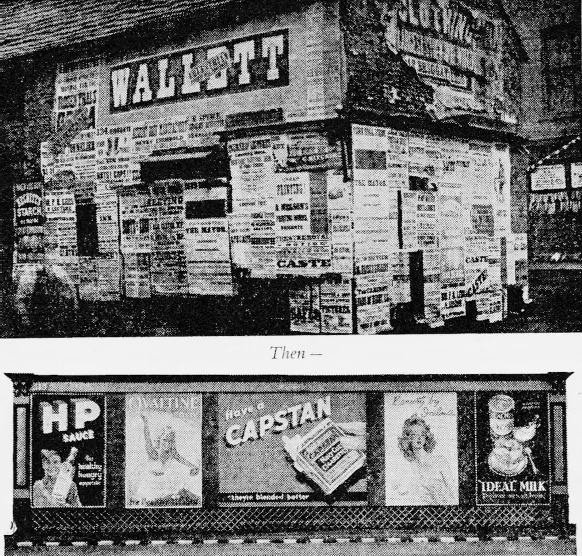

Sheldon, a Leeds advertising company, produced these two contrasting sets of images in 1941. (Countryman magazine)

In May there had been a flow of information for administrators and parents concerning measures to be taken and practical matters in the event of evacuation. When the day came, the child would have a gas mask, essential clothing, a rucksack and of course some food for the initial journey away from home. That was the key phrase: ‘away from home.’ What a terrible few words they are and the official language of circulars had to avoid such emotive topics. Instead, the words used were such as these: ‘A proportion of parents will find it beyond their powers to provide the full list for an immediate emergency, and beyond. No obligation is imposed on the householder to remedy deficiencies.’

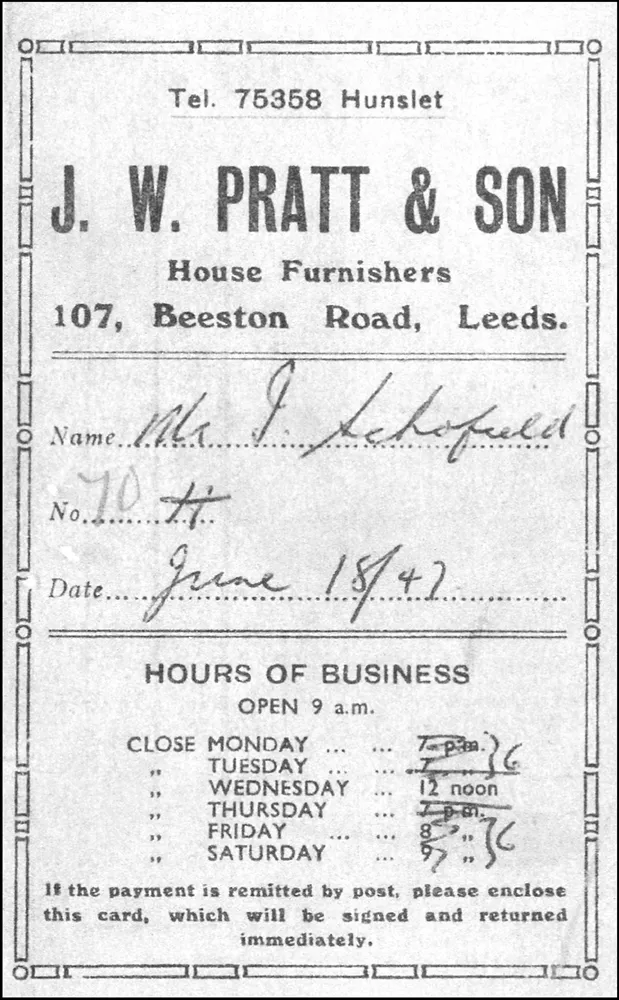

Furniture card: evidence of the emerging availability of the ‘never never’ payment scheme. (Author)

A rehearsal was held at the end of August and this related to the statistics gathered, such as the fact that limitations were likely owing to the poverty of people in many cities and Leeds was one of these. It was suggested that around 3,000 children in the city who received school milk and free meals came from families who could not afford to provide the stipulated clothing and food for the evacuation. Other shortcomings were noted as well, such as the low number of Leeds children who arrived in Hemsworth: just 280 out of the planned 743.

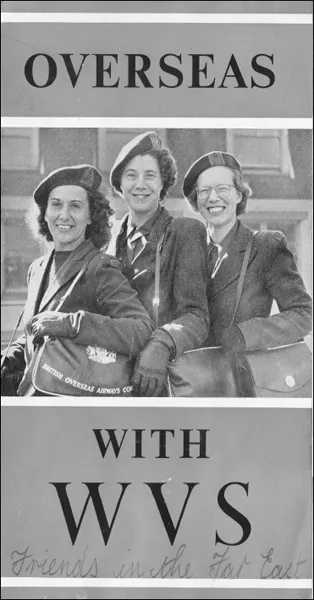

The front page of a booklet showing the happiness involved in WVS work across the globe. (Author)

Then the real thing came along. In the first days of September, following rehearsals on 28 to 30 August, the actual evacuations started to happen. All schools in Leeds received the order, on the last day of August, to evacuate the following day. The order did not mean that war was certain, but of course ordinary folk felt that such was the case. On 1 September, everything moved into place: the children gathered, with luggage labels on them, carrying bags and gas masks; meeting them was a cluster of various support workers including WVS staff and medical professionals. The Tannoys referred to the situation as one in which the children were to have ‘excursions’. The sensible practical measure of having the children escorted to the station and then to the trains by the helpers rather than with parents (who had said their farewells at home) was done smoothly on the whole. Some 40,000 children were to be transported to a range of places: mainly the Dales, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire.

One man recalled that he went from Holbeck to Gainsborough and all turned out well: ‘I truly believe that God was looking down on me that day for my name was called outside the gate of 32, Lime Tree Avenue... right from the beginning they were very kind to me.’ Some went to various halls and homes in North Yorkshire. Simon Chalton told Colin Wells, for instance, that

Children from St Agnes School, Headingley, before evacuation. (Down Your Way magazine)

In anticipation of the outbreak of war Miss Harvey decided to move the school to North Yorkshire and eleven of us pupils were to go to her... It was a bright and sunny afternoon when we arrived at Nunnington Hall. Mrs Fife met us and we were given tea in the small orchard... I remember this clearly, including somebody singing ‘Underneath the spreading chestnut tree/Mr Churchill said to me/ if you want to keep your country free/Join, join the ARP.’

As one would expect, there have been several memories from Gainsborough people about the wartime school experience and the Leeds evacuees. In fact, the evacuees included Leeds teachers as well as children. At Gainsborough Parish Church C of E Aided Primary School, a note in a memorial volume notes the recall of the Leeds teachers:

After yesterday’s weekly meeting of the Headteachers, Mr H.B. Sweetman, Headmaster of the Bramley National School, made the following statement: ‘The staffing of the schools and the excellent way in which everything is working, has enabled the Director of Education for Leeds to recall a considerable number of teachers. The whole scheme of evacuation is working exceptionally well, and we have nothing but praise for the way they have co-operated.’

The whole operation had indeed been a success. We also have a glimpse in the records about the strictness of the teaching: ‘The Gainsborough boys soon realised that the visiting male teachers had a strict control over their pupils and on certain occasions if one of their charges was misbehaving the teacher was not averse to releasing the board rubber or chalk.’

There were small issues involved, of course, as there would be in any such ad hoc liaison. Norman Slater, contributing to the Gainsborough memorial volume, told the editor: ‘There was another problem regarding our visiting evacuees and that was the religious aspect. Because a large number of them were of the Catholic faith, when the school had religious classes or daily prayers, the Catholics had separate classrooms for their instruction.’ However, in spite of such differences, real friendships were formed between the Gainsborough and Leeds children.

Towards the end of the war, when the Leeds children had returned home, ironically, Gainsborough was bombed from 3 to 4 March 1945. There were deaths, and one was Mr Sutton, the school caretaker at the C of E School. One memory given of the bombing explains: ‘All the windows in the western end of the school were broken, and there were fresh red chipped-out bricks in the wall where bomb shrapnel had hit.’ There are many memoirs available on the experience of evacuation and one of the most evocative and detailed was included in the East Leeds Magazine in 2011, written by Alan Mills. Mr Mills was sent to Otley and he describes the events very vividly:

Eventually we arrived outside the Congregational Church in Otley. Despite being only twelve miles up the road from Leeds, a place I’d never visited or even heard of, I remember vividly the hush on the bus, no excitement, just a solemn silence as we awaited to see what would happen next. Within minutes some homely ladies from Otley W.V.S., acting as billet officers, took us in hand and began the operation of organising us into foster homes.

He describes the sharp contrasts such as the landscape and the engagement with a rural milieu: ‘From our arrival in Otley the weather was beautiful, warm sunshine, the heat of the sun and the September mists rising from the river combining to make a dense haze.’

One of the strangest instances of evacuation has been recalled by Alan Bennett. In his essay Past and Present, he recalled that his father took the family to Wilsill in Nidderdale. He wrote:

There were a few houses, a shop, a school and a church, and though we were miles from any town, even here the stream had been dammed to make a static water tank in readiness for the fire-fighters... My father was a shy man... to knock at the door of the farm and ask some unknown people to take us in still seems to me to be heroic.

No doubt many people made their own arrangements for evacuation. There would have been a large number of Leeds families who had relatives scattered around various corners of Yorkshire and who would have taken them in.

Also from 1939, the Kindertransport process began in earnest. This is the German term applied to the series of rescues undertaken to bring Jewish children out of Nazi Germany where the ‘Final Solution’ was beginning to enter its first stage and Jewish people were under threat of deportation to camps within the Holocaust system. One formative event in this was the infamous Kristallnacht of 9/10 November 1938 in which the windows of Jewish-owned properties were smashed in German cities.

The transport began when individual people or government-backed sponsors began the rescue of the children. The first group arrived at Harwich on 2 December 1938 and after that, groups such as Reich Representation of Jews in Germany or the Jewish Community Organisation were involved. The children would travel by train to the seaports of Belgium and Holland, and sometimes from Hamburg in Germany. After arrival in Harwich, there would be dispersal to the various homes of sponsors and volunteers. In all, approximately 10,000 children were saved in this way, being taken from several countries. There was only one rather dark cloud over this bright situation: in 1940 Britain interned about 1,000 of these children and kept many in a camp on the Isle of Man.

Many of the Kindertransport children came to Leeds, and of course Leeds has been a significant location for Jewish émigré settlement since the mid-nineteenth century. The media in recent years have featured such biographies and a typical story is that of Ernest Simon, who was featured in 2013 by the Jewish News. Mr Simon came to live with a Jewish family in Leeds who took good care of him. He recalled: ‘I reminded myself how lucky I had been. My parents had taken the incredibly difficult decision in 1938 after Kristallnacht to send me to England on a Kindertransport from Vienna.’

He was just 8 years old when he said farewell to his mother and younger brother at the Vienna railway station; he recalls that a number was hanging from his neck and that he went on a ship leaving from the Hook of Holland. Mr Simon has clear memories of growing up in Leeds: ‘Soon after arriving in Leeds...I started school. Cowper Street school was in the heart of the Jewish area of Leeds. I arrived wearing my typical Austrian winter school wear – knickerbockers and plus-fours – and was immediately the centre of attention.’

His parents and his brother made it to England too; he was one of the lucky ones. Mr Simon’s family had lived in Eisenstadt, south of Vienna, and he recalled that it was renowned as a place of education and culture but, as he remembered: ‘In September 1938 we and all our Jewish neighbours were compelled to abandon our homes and belongings.’

Another fascinating Leeds life in this regard is that of Edith Goldberg, who died in 2013 after a long life in the city following her arrival by means of the Kindertransport. The Yorkshire Post reported in her obituary that she had come to Leeds at the age of 11 with her sister Irmgard and they had lived with Jewish families. She was born in Kaiserslautern in May 1928, living in a tiny village where 20 out of the population of 200 were Jewish. Edith married Jack Goldberg in 1951 and she then worked in Schofield’s department store until they opened a business in Street Lane.

The Yorkshire Post feature sums up Edith’s situation: she decided to tell her life story ‘in print and video’ and as the reporter commented: ‘Edith’s inspirational story will be used for future educational purposes... to show the true spirit of those who overcame great adversity with courage and fortitude.’

Mention should also be made of the ORT Technical Engineering School in Chapeltown, which took 106 Jewish boys between 1940 and 1942. In April 2013, a blue plaque was pu...