![]()

THE BIG PUSH

1 JULY-17 NOVEMBER 1916

‘You must know that I feel that every step in my plan has been

taken with the Divine help.’

Sir Douglas Haig to Lady Haig before the battle.

‘The news about 8 a.m. was not altogether good.’

Sir Douglas Haig on 1 July.

‘Our battalion attacked about 800 strong. It lost, I was told in hospital,

about 450 the first day, and 290 or so the second. I suppose it was worth it.’

NCO of the 22nd Manchesters.

SUMMARY OF THE BATTLE

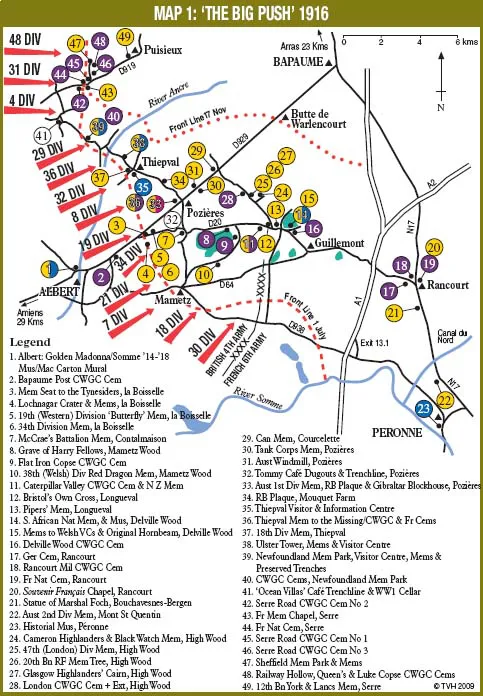

On 1 July 1916 a mainly volunteer British Army of 16 divisions in concert with five French divisions attacked entrenched German positions in the Department of the Somme in France. Over-reliance by the British on the destruction of enemy defences by preparatory artillery bombardment led to almost 60,000 British casualties on the first day and more than 400,000 before the fighting ended on 17 November 1916. The maximum total advance made in all that time was six and a half miles. Total German casualties are estimated to have been about the same as the British and the French were almost 200,000.

OPENING MOVES

Few campaigns of recent history provoke such emotive British opinions as ‘The Battle of the Somme’. Those who study the First World War tend to fall into two main camps: those who are anti-Haig and those who are pro-Haig. But there are those who move from one opinion to the other, according to the quality of debate. Was the C.-in-C. a dependable rock, whose calm confidence inspired all, whose far-seeing eye led us to final victory and who deserved the honours later heaped upon him? Or was he an unimaginative, insensitive product of the social and military caste system that knew no better: a weak man pretending to be strong, who should have been sacked? Doubtless the arguments will continue and more space than is available here is needed for a fair consideration, but there are some immovable elements: for instance the misjudgement concerning the artillery’s effect upon the German wire and the appalling casualties on 1 July 1916. Those casualties, while not sought for by the French, may well have been hoped for by them. At the end of 1915 the French and British planned for a joint offensive on the Somme, with the French playing the major role. Masterminded by Joffre, the plan was (as far as Joffre was concerned) to kill more Germans than their pool of manpower could afford. But when the German assault at Verdun drew French forces away from the Somme, the British found themselves with the major role, providing sixteen divisions on the first day to the French five.

It was to be the first joint battle in which the British played the major role and, in the opinion of some French politicians, not before time. There was a growing feeling that the British were not pulling their weight and a bloody conflict would stick Britain firmly to the ‘Cause’. It was to be the first major battle for Kitchener’s Army following their rush to the recruiting stations in the early days of the war.

It was also to be the first battle fought by Gen Haig as C.-in-C. There was a great deal riding on the outcome of the Battle of the Somme. The British plan was based upon a steady fourteen-mile-wide infantry assault, from Serre in the north to Maricourt in the south, with a diversionary attack at Gommecourt above Serre. One hundred thousand soldiers were to go over the top at the end of a savage artillery bombardment. Behind the infantry – men of the Fourth Army, commanded by Gen Rawlinson, waited two cavalry divisions under Gen Gough. Their role was to exploit success.

WHAT HAPPENED

The battle may be divided into five parts:

| Part 1. | The First Day | 1 July |

| Part 2. | The Next Few Days | 2 July + |

| Part 3. | The Night Attack/The Woods | 14 July + |

| Part 4. | The Tank Attack | 15 Sept |

| Part 5. | The Last Attack | 13 Nov |

Part 1. The First Day: 1 July

At 0728 hours seventeen mines were blown under the German line. Two minutes later 60,000 British soldiers, laden down with packs, gas mask, rifle and bayonet, 200 rounds of ammunition, grenades, empty sandbags, spade and water bottles, clambered out of their trenches from Serre to Maricourt and formed into lines fourteen miles long. As the lines moved forward in waves, so the artillery barrage lifted off the enemy front line.

From that moment onwards it was a life or death race, but the Tommies didn’t know it. They hadn’t been ‘entered’. Their instructions were to move forward, side by side, at a steady walk across No Man’s Land. It would be safe, they were told, because the artillery barrage would have destroyed all enemy opposition. But the Germans were not destroyed. They and their machine guns had sheltered in deep dugouts, and, when the barrage lifted, they climbed out, dragging their weapons with them.

The Germans won ‘the race’ easily. They set up their machine guns before the Tommies could get to their trenches to stop them, and cut down the ripe corn of British youth in their thousands. As the day grew into hot summer, another 40,000 men were sent in, adding more names to the casualty lists. Battalions disappeared in the bloody chaos of battle, bodies in their hundreds lay around the muddy shell holes that pocked the battlefield.

And to what end this leeching of some of the nation’s best blood? North of the Albert-Bapaume road, on a front of almost nine miles, there were no realistic gains at nightfall. VIII, X, and III Corps had failed. Between la Boisselle and Fricourt there was a small penetration of about half a mile on one flank and the capture of Mametz village on the other by XV Corps. Further south, though, there was some success. XIII Corps attacking beside the French took all of its main objectives, from Pommiers Redoubt east of Mametz to just short of Dublin Redoubt north of Maricourt.

The French, south of the Somme, did extremely well. Attacking at 0930 hours they took all of their objectives. ‘They had more heavy guns than we did’, cried the British generals, or ‘The opposition wasn’t as tough’, or ‘The Germans didn’t expect to be attacked by the French’. But whatever the reasons for the poor British performance in the north they had had some success in the south – on the right flank, beside the French.

Part 2. The Next Few Days: 2 July +

Other than the negative one of not calling off the attack, no General Command decisions were made concerning the overall conduct of the second day’s battle. It was as if all the planning had been concerned with 1 July and that the staffs were surprised by the appearance of 2 July. Twenty-eight years later, on 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, a similar culture enveloped the actions of the British 3rd Division in Normandy. Aggressive actions were mostly initiated at Corps level while Haig and Rawlinson figured out what policy they ought to follow. Eventually, after bloody preparation by the 38th (Welsh) Division at Mametz Wood, they decided to attack on the right flank, but by then the Germans had had two weeks to recover.

Part 3. The Night Attack/The Woods: 14 July +

On the XIII Corps front, like fat goalposts, lay the woods of Bazentin le Petit on the left and Delville on the right. Behind and between them, hunched on the skyline, was the dark goalkeeper of High Wood. Rawlinson planned to go straight for the goal. Perhaps the infantry general’s memory had been jogged by finding one of his old junior officer’s notebooks in which the word ‘surprise’ had been written as a principle of attack, because, uncharacteristically, he set out to surprise the Germans and not in one, but in two, ways.

First, despite Haig’s opposition, he moved his assault forces up to their start line in Caterpillar Valley at night. Second, after just a five-minute dawn barrage instead of the conventional prolonged bombardment, he launched his attack. At 0325 hours, 20,000 men moved forward. On the left were 7th and 21st Divisions of XV Corps and on the right 3rd and 9th Divisions of XIII Corps. The effect was dramatic. Five miles of the German second line were overrun. On the left Bazentin-le-Petit Wood was taken. On the right began the horrendous six-day struggle for Delville Wood. Today the South African Memorial and Museum in the wood commemorate the bitter fighting.

But in the centre 7th Division punched through to High Wood and with them were two squadrons of cavalry. Perhaps here was an opportunity for a major breakthrough at last. Not since 1914 had mounted cavalry charged on the Western Front but, when they did, the Dragoons and the Deccan Horse were alone. The main force of the cavalry divisions, gathered south of Albert, knew nothing about the attack. The moment passed, the Germans recovered, counter-attacked and regained the wood.

There followed two months of local fighting under the prompting of Joffre, but, without significant success to offer, the C.-in-C. began to attract increasing criticism. Something had to be done to preserve his image, to win a victory – or both.

It was: with a secret weapon – the tank.

Part 4. The Tank Attack: 15 September

Still very new and liable to break down, thirty-two tanks out of the forty-nine shipped to France in August assembled near Trônes Wood on the night of 14 September for dispersal along the front, and the following morning at 0620 hours, following a three-day bombardment, eighteen took part in the battle with XV Corps. Their effect was sensational. The Germans, on seeing the monsters, were stunned and then terrified. Nine tanks moved forward with the leading infantry, nine ‘mopped up’ behind. Barely over three hours later, the left hand division of XV Corps followed a solitary tank up the main street of Flers and through the German third line. Then Courcelette, too, fell to an infantry/tank advance.

The day’s gains were the greatest since the battle began. But there were too few tanks and, after the initial shock success, the fighting once again degenerated into a bull-headed contest. The opportunity that had existed to use the tank to obtain a major strategic result had gone. Many felt that it had been squandered. Yet the tank had allowed 4th Army to advance and the dominating fortress of...