- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

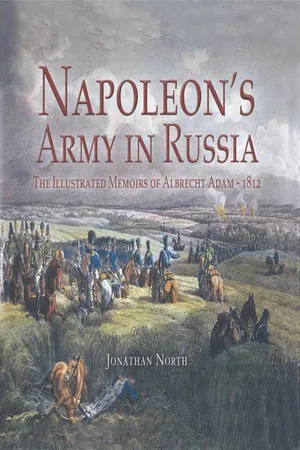

In 1812 Napoleon's magnificent army invaded Russia. Among the half a million men who crossed the border was Albrecht Adam, a former baker, a soldier and, most importantly for us, a military artist of considerable talent. As the army plunged ever deeper into a devastated Russia Adam sketched and painted. In all he produced 77 colour plates of the campaign and they are as fresh and dramatic as the day they were produced. They show troops passing along dusty roads, bewildered civilians, battles and their bloody aftermath, burning towns and unchecked destruction. The memoirs which accompany the plates form a candid text describing the war Adam witnessed. Attached to IV Corps, composed largely of Italians, he was present at all the major actions and saw the conquerors march triumphantly into Moscow. But, from then on, the invading army's fate was sealed and the disastrous outcome of the war meant that the year 1812 would become legendary as one of the darkest chapters in history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Napoleon's Army in Russia by Jonathan North in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

Preface

Introduction

The Plates

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Preface

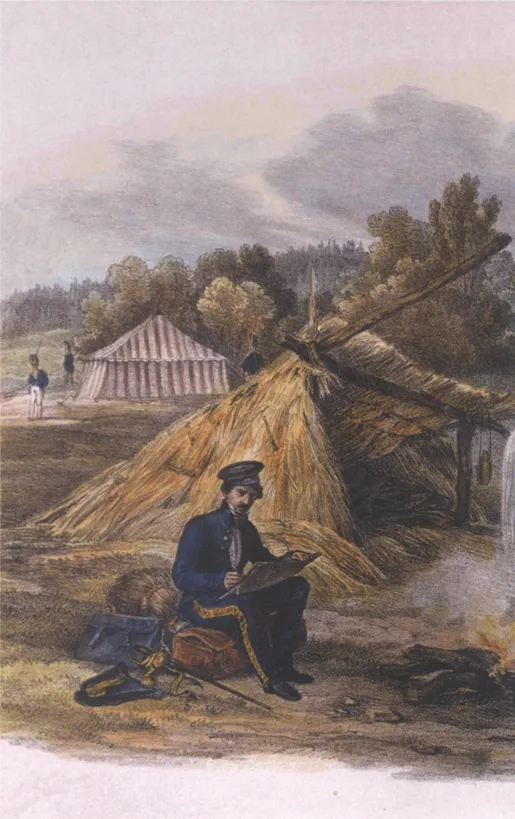

Albrecht Adam was born in Nördlingen, a small free state in southern Germany, on 16 April 1786 to Jeremias Adam and Margaretha Adam. His talent for painting quickly became apparent and as early as 1800 he was painting French troops as they marched and shuffled victoriously through southern Germany. Tutored by Christoph Zwinger in Nuremberg, the young artist made steady progress. In July 1807 he moved to Munich and, two years later, took part in the successful war against Austria. During the course of the campaign he met Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s stepson and Viceroy of Italy. Eugene, who had a Bavarian connection as he had married Princess Auguste of Bavaria in 1806, asked Adam to join his household in October 1809. Later that month, the young artist set out for Italy with a modest salary of 2,400 francs.

In 1812 Adam accompanied Eugene’s staff on the expedition to Russia. He attached himself to the Viceroy’s Topographical Bureau, a small unit of engineers, cartographers and draughtsmen which had been established in 1801. Adam travelled with the IV Corps and accompanied the army on its long, arduous march on Moscow. Labaume, author of a chilling account of the expedition, was one of his associates.

Not long after reaching Moscow Adam decided to return to Germany, depressed, apparently, with what he had witnessed. As he was not obliged to stay, not being part of the military establishment, he obtained permission to quit the French army on 29 September 1812 and, after a harrowing journey, reached Munich on 23 December, just as the remains of Napoleon’s massive army was trickling back over the border into Poland.

In 1815, after peace was restored across an exhausted Europe, Adam returned to Munich and found ample work in the city. With King Maximilian as patron Adam was in a privileged position and was able to execute a number of works for the king as well as for the Wrede, Leuchtenberg, Thurn und Taxis, Metternich and Furstenburg families. He was known in particular for his battle scenes but his great passion was for equestrian studies.

In 1827 he began work on the suite of images gathered together under the title of Voyage pittoresque et militaire. These plates, reproduced here, were based on sketches he had taken throughout the campaign and are of tremendous historical significance. The work was issued by Hermann and Bath in Munich in 1828 and included in the list of subscribers to the volume were Captain von Faber du Faur and Peter Hess, both celebrated recorders of Napoleon’s ill-fated expedition of 1812. Adam says that, originally, the images presented here began life as studies, drawn from his sketches, for large-scale battle scenes. Following the death of Prince Eugene, however, he obtained permission from Eugene’s widow to have them published as coloured lithographs. The lithographs are not the only works to stem from Adam’s participation in the campaign as he made a number of oil on paper studies before issuing the suite presented here. A number of these images now reside in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

Because of Adam’s Bavarian origins (Nördlingen was absorbed by Bavaria in 1802), and Eugene’s Bavarian connection, a number of the lithographs include Bavarian subjects. There are Bavarian troops illustrated in plates 1, 22, 48 and 59, for example. But the majority of the plates illustrate Eugene’s Italian troops as they march along Russia’s endless highways. Inevitably, the images presented here stop in September 1812, before the legendary retreat. Studying the text and pictures, however, might easily lead to the conclusion that the advance into Russia was just as costly and arduous.

The text is taken from the accompanying text used in the Voyage pittoresque. It, in turn, comes from the artist’s journal with some borrowings from Labaume and Ségur. The Epilogue, however, is taken from Adam’s published memoirs.

Adam died in Munich on 28 August 1862 leaving two sons one of whom, Benno, had been born on 15 July 1812.

Particular thanks must go to Digby Smith, Yves Martin, Dr Thomas Hemmann and Massimo Fiorentino for their considerable assistance. I am also grateful to Rupert Harding, for his enthusiasm, and Peter Harrington in Rhode Island.

But I owe especial thanks to my wife, Evgenia, and to my son, Alexander, for their patience.

Jonathan North

2005

2005

Introduction

In the early summer of 1812 masses of troops were gathering. In Poland and eastern Prussia Napoleon’s army, one of the largest ever assembled, began to take up positions along the borders of the Russian empire. Across that border, in Russian-dominated Lithuania, the Czar’s troops were also mobilising. The scene was set for an epic confrontation as two empires were set on a collision course and two emperors, once allies, now rivals, gambled on war to maintain or augment their power.

As recently as 1807 the French emperor and the Czar of all the Russias had met and formed an alliance, effectively carving up Europe between them. France rejoiced in power over Germany and Poland whilst Russia set about relieving Sweden of Finland and a series of wars with the Ottoman Porte. Gradually, but perceptively, the two emperors began to bicker. Napoleon’s plans for Russia did not conform with Russia’s plans, whilst Napoleon’s power in Europe seemed interfering, menacing and on the increase.

By 1811, an ugly year of rumour, both sides were preparing for a confrontation. Efforts were made to resolve differences but Napoleon, a man of war, trusted to his armies to bring Russia to heel once sweet words were no longer working. As 1811 ended troops were marching east to deliver a fatal blow to Russian military might, thereby forcing Alexander to recognise his role in Napoleonic Europe.

Napoleon invested a massive amount of preparation into this imperial adventure. Supplies, waggons and armaments were despatched eastwards in 1811 and early 1812. Plans were made for the use of rivers to ferry supplies forwards and towns in eastern Prussia and Poland were designated as stockpiles and magazines. Napoleon had also lavished attention on attempting to gauge what lay in store for his men once they crossed the border. Agents were sent into Lithuania and the Ukraine. On 16 November 1811 the Foreign Ministry had written to Bignon, Resident in Warsaw, stating that the emperor wanted ‘statistical details of Podolie, Volhynia and the Ukraine; descriptions of the roads; nature of the terrain; the inhabitants; the roads from Lemberg to Kiev and Doubno to Kiev; and the Dnepr river’. Less attention was paid to the question of food and little effort was placed into checking that orders were actually carried out.

Such concerns did not trouble French military planners unduly. They were informed that the campaign should be over quickly. The Russians would be knocked out by one of the greatest armies ever assembled.

The French emperor had troops from nearly every nation in Europe at his disposal as he began to concentrate forces in Germany and Poland in early 1812. By June some 450,000 were available and could call upon reserves and supports on either flank, elements which boosted this total to 600,000 men and 250,000 horses. The majority of the troops were French, or at least serving in French uniform, but a good number were furnished by vassals and allies. There were Italians, Neapolitans, Poles, Bavarians, Badeners, Westphalians, Saxons, Württembergers, troops from smaller German states, troops from the Balkans, Spaniards, Portuguese and Swiss. Even the reluctant Prussians cooperated and the Austrians, so many times an enemy of France, also deployed a force to operate in the Ukraine.

Much of the Grande Armée was young and reluctant – particularly those in the recently expanded armies of the German states and, of course, the Prussians and Austrians. This posed problems in the early stages of the campaign and, for example, on 10 July the 10th Chasseurs were pulled back because ‘due to its lack of ability it is not suited to duty in the frontline’. Even so. Napoleon’s army was one of the most imposing military hosts ever to take the field and considerable effort had gone into uniforming, equipping and training the troops. War was looked upon eagerly by many. On 12 July Berthier wrote to Napoleon that ‘35 pupils of the military school had just finished their artillery examination and they fervently request that they might be allowed to serve in the army under you’. Such attitudes were commonplace in an imperial army accustomed to victory.

In terms of turnout and morale the Imperial Guard and I Corps were particularly magnificent, although other formations could also boast fine troops. Count Bourgoing of the Young Guard describes some of Marshal Ney’s corps:

I studied with awe and respect the French line regiments in III Corps. These regiments were formed by men who had come from the Boulogne camps, where they had trained under the eyes of their marshal. There were no youthful faces here, unlike in our Tirailleurs, for these men bore the martial aspect of veterans.

Such a massive force, however, meant that many elements fell far short of the standards set by Napoleon’s best. Many of the soldiers in Napoleon’s army were reluctant conscripts, and many became even more reluctant as time wore on. Even before the campaign opened desertion was a problem. In March 1812 the 127th Line lost 97 deserters whilst marching from Magdeburg to Stettin. Some contingents were to suffer heavily from desertion and the Bavarians were described as having ‘a mania for desertion’. The French army contained an entire division of reformed deserters (32nd Division, XI Corps) and many line regiments had had to absorb such transgressors in the build-up to war, as Marshal Berthier noted to Napoleon in February 1812:

Sire, the Minister of War has acquainted me with your order, dated 6 February, that 721 deserters, condemned to hard labour, be pardoned and sent on to Wesel. Here they shall be armed and equipped and sent to join the corps currently in Germany. I have the honour of suggesting that these 721 men be assigned to the 4th, 18th and 72nd Line and the 11th Light, which form part of the II Corps of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents