- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

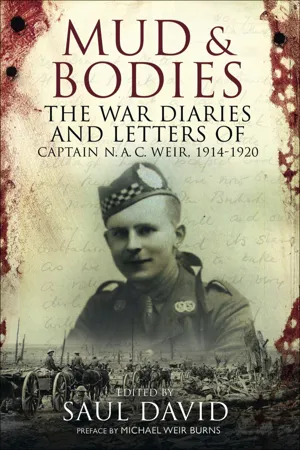

Neil Weir died in 1967, but it was not until 2009 that his grandson, Mike Burns, discovered his diary among some boxes he had been left, and learnt that his grandfather had served as an officer in the 10th Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlander throughout the First World War, seeing action at Loos, the Somme and Vimy Ridge, as well as in staff and training posts. It ends with his work at the War Office during the Russian Civil War of 191920. In the diary, and the accompanying letters which have been collected from various members of the Weir family, we hear the authentic voice of a First World War soldier and get an insight into his experiences on the Western Front and elsewhere. Edited and with introductory text by Saul David, this book is one of the most fascinating accounts ever published of the First World War as experienced by the men who fought it.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.

Service at Home

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, ostensibly to protect Belgian neutrality (which Germany had breached as part of its ‘Schlieffen Plan’ to invade France via Belgium, in the hope that it could avoid a prolonged war on two fronts). Most of the regular British Army at home was at once sent across to France as part of Field Marshal Sir John French’s 150,000-strong British Expeditionary Force (BEF), made up of four infantry divisions and one cavalry division; a further three regular infantry divisions and one cavalry division would soon follow. That left just the Territorial Force of 14 infantry divisions and 14 Yeomanry cavalry brigades in reserve, and to expand the reservoir of manpower that he assumed would be needed to fight a long war, the new Secretary for War, Lord Kitchener, appealed on 8 August for the first 100,000 volunteers.

Kitchener’s aim was to raise a series of New Armies, complete in all their branches, with each one replicating the six infantry divisions of the BEF. This was to be done through the normal regular recruiting channels, rather than through the Territorial Force, and the scheme for the first New Army, or new Expeditionary Force as it was originally called, was announced on 12 August. Six of the eight regional commands – the exceptions were Aldershot and the London District – would each provide an infantry division by recruiting at least one ‘Service’ battalion for every line regiment in their area.

At first the response to Kitchener’s iconic ‘Your Country Needs You’ recruiting poster was slow. But it soon picked up with the daily total rising from 7,000 on 11 August to almost 10,000 a week later, and peaking at 33,000 on 3 September, the highest number of recruits attested on a single day during the whole war. In the first eight weeks, more than 750,000 men between the ages of nineteen and forty had volunteered (Weir among them) to serve for three years or the duration of the war.2

On 25 August, Kitchener predicted the army might expand to 30 divisions. By mid-September this estimate had risen to 50 divisions, and to 70 by July 1915, though it would later be adjusted, in April 1916, to 57 divisions overseas and 10 at home.3 In all there were 30 New Army divisions, divided into 5 armies.

The very first was known as the 9th (Scottish) Division, and it was to a battalion in that formation4 – the 10th (Service) Battalion, The Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders – that Weir was posted as a newly commissioned temporary second-lieutenant on 26 August. He never mentions why he chose that particular unit, or it chose him; his Scottish heritage must have played its part, though he could just as easily have joined the Highland Light Infantry as it, and not the Argylls, was the local regiment for Glasgow where his grandfather was born.

Like all New Army (or ‘Service’) battalions, the 10th Argylls was administered and trained by a cadre of regular officers and NCOs who – as Weir confirms in his diary – were resentful at being left behind when their comrades were shipped to France, and who would have looked down on the untrained volunteers and temporary officers as decidedly second-rate. Most of the ordinary soldiers were Scots from in or near the Argylls’ regimental depot of Stirling.

The 10th Argylls was raised in August in Stirling, and quickly moved down to Aldershot to begin its training. It was there that 2nd Lieutenant Neil Weir joined the battalion on 20 September, having spent the previous three weeks at an Officers’ Training Camp at Churn in Oxfordshire. Like all New Army formations, the 10th was understaffed and underequipped. ‘Variously lacking officers, NCOs, uniforms, kit, modern weapons or even the most basic accommodation for the men,’ wrote one historian, ‘the situation was soon desperate. There was a shortage of specialist personnel of all kinds . . . Any kind of military experience was soon at an absolute premium and many old officers and NCOs were “dug out” and called back to the colours to drill the ranks into some semblance of discipline.’5

To Mrs Edith Weir6

Churn Camp, Didcot

[Monday] 7 September 1914

[Monday] 7 September 1914

Dear Mother,

I hope you are quite well. I think for safety it would be wise to address my letter as:

N. A. C. Weir Esq

10th (Service) Battalion

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Churn Camp

Nr Didcot

10th (Service) Battalion

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Churn Camp

Nr Didcot

There are such tons of letters, and all anyhow, and there are two other camps here besides this one. I hope to get off one week-end.

Yours,

Neil

Neil

To Mrs Edith Weir

Churn Camp, Didcot

Saturday [12? September 1914]

Saturday [12? September 1914]

My Dear Mother,

Thank you so much for your last letter. Over thirty left to-day to join their regiments, and a great majority have gone away until tomorrow night. To-day we were all inoculated against typhoid, and my left arm is smarting very much from it – as everyone’s is.

I have had a letter from M[illegible] and Auntie Bee and a P.C. [postcard] from Uncle. I am glad you are having some good tennis. If possible I shall try and get down for Saturday evening next just to see you, and I should have to start back on Sunday evening to be in here by 10 o’clock. It is now raining hard and is very dreary. I am opening an account at Cox’s the Army Bankers, and they will get my pay in for me and also £20 towards kit. I know the kit will be over £20, as everything is so expensive, and in the end I may have to draw on my Savings Bank. We are charged 7/ – [7 shillings or 35p] a day and extras here, which I shall pay out of my earnings which amount to about 9/ – a day. Tomorrow we have a slack day so I hope it will be fine. Don’t forget Berrow’s [Berrow’s Worcester Journal]7 will you? I hope you and Dorothy are well and you were successful in your exam.

No time for more.

Yours,

Neil

Neil

To Mrs Edith Weir

Churn Camp, Didcot

Thursday [24 September 1914]

Thursday [24 September 1914]

My Dear Mother,

I hope you are quite well. Please excuse me writing on this awful paper, but my note-paper has run out. I hope to come back from here tomorrow (Friday) and I shall travel by train reaching Shrub Hill at 4.41. I shall have my box and a small parcel so could Albert meet me in the trap [and pony] there, or else I will come on to [the next station] by train arriving at 5:33 and stay for tea in Worcester. You need not send an answer about this as I shall do what I have mentioned if Albert is not there. I shall have to join my regiment on Sunday evening or Monday morning. I cannot be quite sure yet if we can go tomorrow (Friday), but if not we shall certainly leave on Saturday and then I should travel by the same train as if I was travelling on Friday.

I will let you know by wire on Friday morning if I am coming.

Goodbye.

Yours,

Neil

Neil

P.S. I have not heard from you for ages – but I expect you are very busy. We are never told when we are leaving here until a few hours before.

War Diary

Summer/Autumn 1914

It was on [Sunday] the 20th of [September], 1914, that I sailed into Aldershot Railway Station feeling very much like a boy going to his new school. What a feeling! One had a very vague idea as to what the army was really like. Personally I thought that it was an institution where it was necessary to get everything done by brute force, that the senior officers went for the subalterns in the same way that the NCOs went for the men.

But here I was at Aldershot feeling very self-conscious as I stood on the platform in my new uniform while a porter was getting my new valise bag out of the van. Timidly I enquired the way to Talavera Barracks where I had been ordered to report; the porter didn’t know. But another man dressed in civilian clothes had heard my question and informed me that he was also on his way to those barracks. Here was luck. I should have a companion to join me when the time came to report. He told me that his name was Knowling. I told him mine was Weir and away we went off together in a cab to Talavera Barracks.

It so happened that Talavera is quite near to the station so we soon alighted at the Officers’ Mess, a grim looking building, and it was at the door I met the first Argylls officer I had seen. He told us the way to the Orderly Room where we had to report and he also informed us that he was Mess President. That officer turned out to be Captain A. G. Wauchope. He also kindly told us where the Quartermaster could be found. It was he that allotted us rooms. Here my first introduction to Weller! ‘No room for you, young men’ ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Glossary

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. - Service at Home

- 2. - Service in France

- 3. - Into Battle

- 4. - The Ypres Salient

- 5. - ‘Plug Street’

- 6. - Rest and Training for the ‘Big Push’

- 7. - The Battle of the Somme

- 8. - Vimy Ridge

- 9. - Back to the Somme

- 10. - Service with an Officer Cadet Battalion

- 11. - Reserve Battalion

- 12. - Staff Learner

- 13. - Back to the 3rd Argylls

- 14. - War Office

- 15. - The Russian Civil War

- Postscript

- Appendix - Final Farewells

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mud & Bodies by Saul David in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.