- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

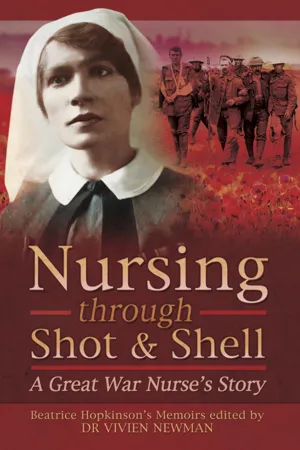

Nursing Through Shot and Shell is the previously unpublished memoir of Beatrice Hopkinson, who served in France as a Territorial Nursing Sister from 1917-19. Beatrice worked close to the front line at casualty clearing stations, and her poignant account reveals the intense strain: 'I never realized what the word duty meant until this War. To stand at one's post, never flinching and trying to keep the boys cheerful; all the time wondering when our time would come.' The memoir reveals the lighter side of wartime life, with entertainments, travel and enduring friendships. Beatrice also describes the practical realities of war in vivid detail sleeping in dug outs, dodging bombs and avoiding rats 'as big as a good sized kitten'. A fascinating, close-up view of one women's life during wartime.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nursing Through Shot & Shell by Vivien Newman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

The Historial Background to Beatrice Hopkinson’s Diary

Army Nursing: ‘Jobs for the Ladies’

During the First World War, the women of the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) captured – and indeed still capture – the public imagination. Dubbed the ‘Roses of No-Man’s Land’, lauded by the contemporary press and immortalised in memoirs, fiction and on the small screen, these generally well-born young women have incorrectly become synonymous with the Nursing Services of the First World War.

Their commitment and dedication is beyond question and many paid with their lives for their service to the British Army. However, they were nursing auxiliaries and the professional nurses of the permanent Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service (QAIMNS), the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service (QARNNS), their Reserves, and the Territorial Forces Nursing Service (TFNS), were the backbone of the military and naval nursing services.

Since the days of ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ and long before, albeit unofficially, Britain has called upon her women during times of war. But it was in 1860, six years after the Crimean War ended, that women first entered military hospitals. Florence Nightingale’s endeavours to create a body of military nurses had borne fruit and the Army Training School for Military Nurses was established at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Netley, Southampton. It would be another 20 years before the Army Nursing Service (ANS) was formed. This embryonic service’s stringent code of regulations was rigidly attentive to aspiring recruits’ social background. Aged between 25 and 35, they should be of high social status, and ideally daughters or widows of army officers. According to the then Surgeon-General, Sir William Hooper, this ‘entail[ed] a good social qualification’.

In 1882, with Florence Nightingale’s order, ‘your every word and act [should] be worthy of your profession and your womanhood,’ ringing in their ears, a small, carefully chosen group of nurses from the fledgling ANS accompanied the British Army overseas, bound for the now long-forgotten Egyptian Campaign. They beat a path that thousands of army nurses, including Beatrice Hopkinson, have since trodden with dedication, distinction and scant regard for personal safety.

If this 1882 campaign and those of the following 17 years made little impression upon most civilians, then arrangements for the nursing of soldiers made even less. Few civilians would have read the May 1890 Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine article about ‘Her Majesty’s Nursing Sisters’, which disclosed that there were a total of 60 army nurses working in 16 military hospitals in the United Kingdom and overseas.

It was the Second Boer War (1899–1902) which revolutionised both army nursing and public interest therein. In 1899, the one Lady Superintendent, 19 superintendents (senior nursing sisters), 68 sisters and the 100 members of the Army Nursing Service and Army Nursing Reserve (all of impeccable social status), found themselves tasked with caring for the largest army Britain had ever sent into combat overseas. As would happen 15 years later, these initial numbers were soon found to be woefully inadequate.

Eventually, 22 general hospitals were opened in South Africa, each staffed by about 20 nurses. Attired in a suitably adapted uniform, including ‘canvas gaiters as protection against snakes’, these so-called ‘gentlewomen’ soon discovered, in the words of Georgina Pope of the Canadian Nursing Reserve, that, ‘We too were soldiers.’ Georgina nursed both in the ‘huts at Wynburg and under canvas at Rondebosch’ where, at times, she made what she considered ‘a too intimate acquaintance with scorpions and snakes.’ In South Africa, nurses experienced conditions that would become familiar to women who served in Britain’s next conflict. Writing in the British Journal of Nursing, Georgina Pope explained that, ‘Hanging in our mess was a copy of orders to be observed when attacked, &c. Several mornings we wakened to hear the boom of guns.’

Some of the nurses in this opening war of the twentieth century were trapped in the infamous Siege of Kimberley, where they treated Boer prisoners as well as their own wounded and sick. Others were at Ladysmith, where General White singled out for praise the nurses who ‘maintained throughout the siege a brave and protracted struggle against sickness under almost every possible disadvantage, their numbers being most inadequate for the work to be done.’

There were nurses too at Mafeking, whose relief was greeted with national jubilation. In his Mafeking Dispatch, Lord Roberts specifically mentioned the army nurses who ‘worked with the greatest zeal and self devotion throughout the siege.’ He drew attention to the ‘heavy work, frequently carried out under fire … It was largely due to their unremitting devotion and skill that the wounded, in so many cases, made marvellous recoveries, and the health of the garrison remained so good.’

Army nurses also shared many of the hardships of the troops they had gone overseas to nurse. In one of the most remote outposts, Captain William Dobbin saw Australian nurses:

on their knees scrubbing and cleaning … to receive the patients, and in the middle of their work 10 or 12 sick and dying men dumped down from an ox wagon – no orderlies detailed, no native servants. The nurses would be obliged to take off some of their own clothing to make pillows for the sick men, and then go outside to cook food under a raging sun.

What is as noticeable in the writings of these South African War nurses, as in First World War nurses’ accounts, is their admiration for their patients. ‘The arrival of this convoy was the most pitiful sight,’ wrote Georgina Pope, ‘many of the men being stretcher cases shot through thigh, foot or spine. What struck one most was the wonderful pluck of these poor fellows who had jolted over the rough veldt in ambulances and then endured the long train journey.’

As they would do in the 1914-18 war, nurses also shared the highs and lows of their daily activities in their letters home. Writing to her sister Rosie from ‘this Godforsaken country’ at 11.00pm on Good Friday, 28 March 1902, Kate Luard (who returned to service in 1914, once again writing prolific letters) explained how she had ‘been on the trot’ since 8.00am. She recounted that, ‘The wards are awful busy again – at least mine are – & on Easter Day we get the Klerksdorp wounded & shall have a high old time.’ Three hours off-duty where, astride her horse Ginger, Kate ‘jump[ed] the trench, and then [went] bucketing over the veldt to the tops of Angel Kopjes with heaven born views and Transvaal colours,’ left her ready to cope with her patients and her ‘deaf and worried orderly’, even though both patients and orderly were ‘rather trying tonight’. Although some off-duty time was located where possible on a daily basis, it appears that after a year’s service nurses got ten days’ leave, which they frequently spent in Natal.

Although nursing duties form the bulk of the writings of both the South African and First World War nurses, women from both conflicts also found time to comment on the food they resorted to eating. One nurse was unimpressed by ‘Trek Ox’ which ‘was so tough that it is difficult to tackle’. At Ladysmith, although Kate Driver was happy to eat horse, she ‘cannot say the same for the ‘cow-heel jelly made from the horse hoof which was occasionally available to us nurses. It was most sickly, and often by the time it reached our hospital, it was fermenting. It was dyed mauve – as an encouragement I suppose.’ Georgina Pope found that although fresh milk was non-existent, ‘condensed milk, beef-tea, and champagne’ were plentiful.

Georgina Pope’s summing up of her experiences in South Africa could have been penned by a Great War nurse: ‘I deemed it a great privilege to aid in caring for the sick and wounded, and while the hardships necessarily endured in such a campaign have faded from my mind, I still often seem to hear the “Thank you, sister,” of the grateful soldier.’

Unlike Britain’s other late nineteenth century wars, this conflict did impact upon the national consciousness, as stories, both of the wounded and of the nursing service, gained wide press coverage. Just under 40 nurses (including one Australian) died of disease; Rudyard Kipling praised the women’s sacrifice, imagining their ‘little wasted bodies, ah, so light to lower down’ into their graves. The dubious honour of being the first woman whose name is engraved on a war memorial (in St Helen’s, Lancashire), fell to Army Nursing Reserve Sister Clara Evans. She is named alongside local men who also ‘Died On Active Service’ in South Africa. Sister Dorlinda Bessie Hyland, another of the 47 nurses who died during the campaign, is also mentioned on a plaque in the Trinity Reformed Church, Lancaster.

A number of the veteran nurses of this conflict returned to the fray a decade later. Perhaps, like old soldiers, they helped to steady the nerves of the younger nurses working close to the guns for the first time. As we shall see in Beatrice’s diary, nurses could find themselves calmly performing their duties as battle raged close by. Yet, even old South Africa hands would be horrified by the new types of injuries and wounds they were called upon to deal with. South Africa veteran Kate Luard was not alone in feeling that the ‘wounds of the Boer War were pin-pricks’ compared to what nursing personnel now faced. The most famous of the South Africa nursing veterans was Dame Maud McCarthy who, by 1910, was principal matron at the War Office. McCarthy arrived in France to take up her post as Matron-in-Chief to the BEF in August 1914.

By the time the very first army nurses embarked from Folkestone on 15 August 1914, the Service to which they belonged had been significantly re-organised. A Royal Warrant of 27 March 1902 had brought the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) into being. Over a decade later, the social status and educational background of aspiring recruits to this new service remained paramount. ‘Profession or Occupation of Father’ was the question asked immediately after name, date and place of birth on the initial application form. ‘Unsatisfactory social status’ could still lead, even during the Great War, to a nurse’s application being rejected, irrespective of her professional skills.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the QAIMNS had struggled to find enough recruits of suitable background and in August 1914 it was under strength. A total of 297 QAIMNS members – matrons, sisters and staff nurses – were employed in military hospitals at home and overseas. During the Great War these numbers remained unchanged. It was considered unwise to permanently employ more women than would be needed when hostilities ceased. Women who resigned were replaced, but the many thousands of nurses who were recruited to the Army Nursing Services during the war were on short-term contracts (‘as long as my services are required’), with clauses enabling the War Office to terminate their employment at its convenience.

In 1908, the Territorial Forces and the Territorial Forces Nursing Service (TFNS) had been formed specifically for Home, as opposed to Overseas, Service. The social requirements for this new nursing service were less stringent and no mention was made of background, although professional requirements were high. Candidates had to be over the age of 23 and have already completed three years’ training in a recognised hospital – these did not include fever, or women and children’s hospitals, although this rule was relaxed in August 1915. These nurses remained civilians; they received no additional pay; and had to confirm their commitment to the TFNS on an annual basis.

Apart from the Territorial matrons, who spent a week training in military hospitals every two years, no additional military nursing training was considered necessary. Like the QAIMNS, TFNS members mobilised immediately when war was declared, probably only anticipating serving in military hospitals at home. Few would have guessed that between 1914 and 1918, of the 8,140 nurses who enrolled in the Service during hostilities, 2,280 would serve overseas. Forty-eight gave their lives, including six who were killed by enemy action, not to mention those who later suffered debilitating mental after-effects, as one of Beatrice Hopkinson’s overseas matrons would do. Reading Beatrice’s memoir, it seems surprising that the numbers of fatalities were not higher.

During the decade when the Army Nursing Service was being transformed, civilian nursing was also undergoing its own travails. In 1905 a Select Committee had reported in favour of State Registration of nurses – hitherto the profession had been largely unregulated. Doyenne of British nursing Florence Nightingale was amongst the anti-regulation voices. She believed nursing was a vocation that could not and should not be ‘taught, examined or regulated’. The dispute rumbled on, the final Bill leading to State Registration only being passed by Parliament in 1919.

In 1908, the foundation of a Fever Nurses’ Association had led to a scheme of fever training. The British Journal of Nursing (BJN) hoped and believed that this would lead to an improvement both in the training and the status of fever nurses, with the end result being ‘an increase in the popularity’ of fever nursing, as well as crucially, ‘enhancing the status’ of nurses working in fever hospitals. The subtext here appears to be that those trained in such hospitals were deemed of lower status than those who had trained in the main teaching hospitals from where the QAIMNS were predominantly drawn. Nursing was far from immune to the contemporary angst about social status.

Beatrice Hopkinson: From Chambermaid to Nurse

It is unlikely that the early travails and formation of the various military nursing services between 1880 and 1908 would have been known, or indeed of interest, to the Hopkinson family. That Beatrice herself would become a military nurse who not only served with the British Army overseas but also nursed under enemy fire, would have seemed unimaginable during her childhood.

Like their coal miner, shoe-maker and carter neighbours, George and his wife Damaris were undoubtedly more concerned with the everyday demands and needs of their rapidly increasing family than with the welfare of soldiers fighting in distant campaigns. By 1901 George had risen from the position of grocer’s assistant to a grocer’s manager, but in 1900 tragedy had struck the family, bringing Beatrice’s childhood to an abrupt end at the tender age of 11.

Thirty-five-year-old Damaris had died whilst carrying her seventh child and with four younger siblings, Beatrice and her elder sister Gertrude would have found themselves shouldering many of the responsibilities that, in happier circumstances, would have been their mother’s. An ability to both care for others and cope calmly with whatever hardships and dangers came her way appears to have been a hallmark of Beatrice’s war service.

In 1908, George re-married. The 1911 census reveals that he and his youngest daughter were residing with his in-laws near Sheffield. Damaris’ other children were dispersed; the census reveals that 15-year-old Edith was a kitchen maid in Sheffield, while joiner Charles and plumber’s apprentice Wil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword: A Heroine in the Family

- Introduction: The Publication of the Diary

- Chapter I: The Historical Background to Beatrice Hopkinson’s Diary

- Chapter II: Beatrice Hopkinson’s War Diary, 1914–1918: ‘My Experiences at the Front’

- Notes on the Diary Text

- Appendix I: Letter from Dr Charles H. Aylen, 1918

- Appendix II: An Account Written by Dr Charles H. Aylen on Armistice Day, 1922

- Appendix III: ‘A Mother’s Prayer’: Poem by Beatrice Hopkinson