- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

One of Our Submarines

About this book

"[Young] immortalized his distinguished war service as a submariner in the bestselling autobiography,

One of Our Submarines . . . [a] gripping memoir."—

The Guardian

"In the very highest rank of books about the last war. Submarines are thrilling beasts, and Edward Young tells of four years' adventures in them in a good stout book with excitement on every page. He writes beautifully, economically and with humor, and in the actions he commands he manages to put the reader at the voice-pipe and the periscope so that sometimes the tension is so great that one has to put the book down."— The Sunday Times

"No disrespect to the big screen, but you can't beat a book for digging out the details. And the details feel even better if the author is someone who's been there. So, at least take the time to read Das Boot, the autobiographical novel by Lothar-Günther Buchheim. And, for the British perspective, read One of Our Submarines by Edward Young."—The Mouldy Books

"He tells his story in a modest, clear, and amusing way that is a delight to read."—not too much

"In the very highest rank of books about the last war. Submarines are thrilling beasts, and Edward Young tells of four years' adventures in them in a good stout book with excitement on every page. He writes beautifully, economically and with humor, and in the actions he commands he manages to put the reader at the voice-pipe and the periscope so that sometimes the tension is so great that one has to put the book down."— The Sunday Times

"No disrespect to the big screen, but you can't beat a book for digging out the details. And the details feel even better if the author is someone who's been there. So, at least take the time to read Das Boot, the autobiographical novel by Lothar-Günther Buchheim. And, for the British perspective, read One of Our Submarines by Edward Young."—The Mouldy Books

"He tells his story in a modest, clear, and amusing way that is a delight to read."—not too much

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access One of Our Submarines by Edward Young in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION | |

Part One APPRENTICESHIP | |

CHAPTER | |

| I | MY FIRST DIVE |

| II | MY FIRST PATROL |

| III | DISASTER |

| IV | “THE BAY” AND NORTH RUSSIA |

| V | FIRST LIEUTENANT |

| VI | MEDITERRANEAN |

| VII | RECALLED HOME |

| VIII | “PERISHER” |

| IX | MY FIRST COMMAND |

Part Two H.M. SUBMARINE “STORM” | |

| X | BUILDING |

| XI | TRIALS AND WORKING-UP |

| XII | INSIDE THE ARCTIC CIRCLE |

| XIII | PASSAGE TO CEYLON |

| XIV | IN THE NARROWS: MALACCA STRAITS |

| XV | BETWEEN PATROLS: CEYLON |

| XVI | ANDAMAN ISLANDS |

| XVII | CLOAK AND DAGGER |

| XVIII | DESTINATION PENANG |

| XIX | MERGUI ARCHIPELAGO |

| XX | GUN ATTACK ON CONVOY |

| XXI | THROUGH THE LOMBOK STRAIT |

EPILOGUE | |

THE SHIP’S COMPANY | |

INTRODUCTION

THE average man’s almost superstitious horror of submarines is surely due to ignorance of how they work and of what the life is like. One of my reasons for writing this book was to try to remove that ignorance and to show what a fascinating life it is. Some people genuinely suffer from claustrophobia; others imagine they would do so inside a submarine, yet cheerfully travel in aeroplanes and underground trains. It is, I suppose, a matter of temperament. In spite of its uncomfortable moments I found wartime life in a submarine preferable to being shelled in a trench knee-deep in mud, or being shut up in the belly of a tank in the heat of a desert battle, or bombing Germany night after night, or working down in the engine-room of any large surface ship.

I once heard a junior submarine officer, in the presence of his commanding officer, refer to submarine pay as “danger money.” “DANGER?” roared the C.O. “Danger! What you get extra pay for, my boy, is skill and responsibility. What the hell do you mean, danger?”

In times of peace submarines rarely hit the newspaper headlines unless something goes wrong and one of them is sunk; and then every man who has never been to sea is ready with suggestions for raising her off the bottom and getting the men out. Unfortunately this aspect of the submarine service has acquired a grossly exaggerated importance in the public eye, and every time there is a disaster we hear on all sides well-meaning people demanding more safety devices and better methods of escape. These demands never come from submariners themselves. A submarine is a war machine, and though reasonable safety devices are essential, and indeed are continually being improved, they must take second place to fighting efficiency. Fatal railway accidents could be abolished if all trains were limited to a speed of five miles an hour, and the safest submarine in peacetime (but not in wartime!) would be one that could not dive at all. The submarine service prefers to concentrate rather on making its ships and its men so efficient that the chances of an accident are reduced to the minimum. And though submarines travel thousands of miles every year, surfaced and submerged, fatal accidents are in fact remarkably rare. My own story does happen to include one of the rare disasters, but I hope the perspective of the whole book will reveal the incident in its proper light and even help to underline the point I am trying to make.

I wish to thank my old shipmate Mike Willoughby, not only for putting me right on several technical and historical points, but also for making the black-and-white drawings which are scattered through the book. The diagrams on the end-papers and on page 16 are his too. I find I have nowhere mentioned that in addition to his other attainments he is also an inventor. During the war Mike invented an entirely new method of firing torpedoes from a submarine, illustrating his proposals with some first-class engineering drawings which received serious consideration at the Admiralty. He also designed an improved submarine camouflage, which was first tried out on Sealion and later adapted by some of us for use in the Far East.

I wish also to thank my friend Barnett Freedman (together with the Trustees of the Tate Gallery) for allowing me to reproduce a photograph of his painting of a submarine control-room. I was first introduced to Barnett when he was working on this picture as a War Artist at Fort Blockhouse, Gosport. “Not the Barnett Freedman?” I exclaimed amidst the Philistines, and made a friend for life. He was not content, as many artists would have been, to fudge the complexity of his subject by a cowardly impressionism; instead he spent several weeks, months even, going to sea and diving in the submarine until he knew the exact function of every lever, pipe and valve. The result is not only a fine picture but the most detailed and technically accurate drawing of a control-room that has ever been made.

For their valuable help in checking the typescript and the proofs, and for many suggestions gratefully adopted, I am indebted to David Garnett, Rupert Hart-Davis, Ruari McLean, and Commander M. R. G. Wingfield, D.S.O., D.S.C., R.N.

I wish to thank Commodore B. Bryant, D.S.O., D.S.C., R.N., for lending me several photographs, particularly those taken through his periscope and here reproduced opposite page 64; my First Lieutenant in Storm, Brian Mills, D.S.C, R.N., for the photographs numbered 27, 30, 34, 35 and 37; Mr N. F. Carrington, formerly Lieutenant R.N.V.R., for sending me many years ago the photograph of Saracen in Malta which faces page 97; also Captain B. W. Taylor, D.S.C., R.N. (Chief of Staff to Flag Officer Submarines) and Mr E. G. A. Thompson in the Department of the Chief of Naval Information, Admiralty, for their helpful co-operation.

Finally I thank my wife, not only for typing the final draft of the book, but for her forbearance during my spare-time labours over two-and-a-half years.

E. Y.

July 1952

PART ONE

APPRENTICESHIP

So ignorant are most landsmen of some

of the plainest and most palpable wonders

of the world, that without some hints

touching the plain facts, historical and

otherwise, of the fishery, they might scout

at Moby Dick as a monstrous fable, or

still worse and more detestable, a hideous

and intolerable allegory.

of the plainest and most palpable wonders

of the world, that without some hints

touching the plain facts, historical and

otherwise, of the fishery, they might scout

at Moby Dick as a monstrous fable, or

still worse and more detestable, a hideous

and intolerable allegory.

Moby Dick

HOW A SUBMARINE DIVES

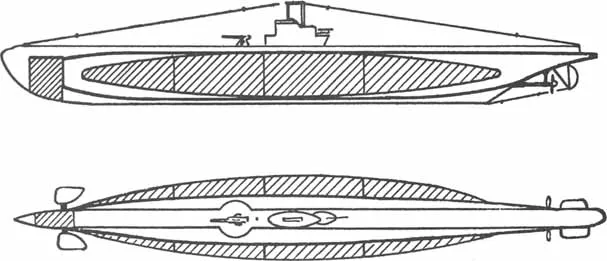

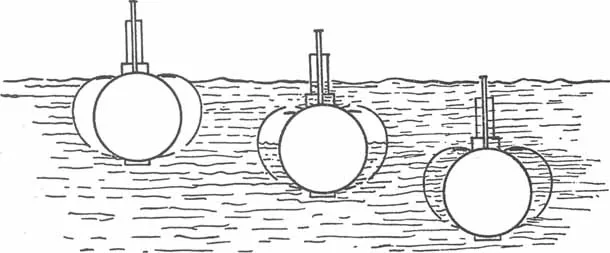

A submarine dives by allowing her main ballast tanks to fill with water. In the above diagrams (side view and bird’s-eye view) the main ballast tanks are indicated by shading. These tanks are outside the pressure-hull. On the surface they are full of air; when the air is allowed to escape, through vents at the top of the tanks, the sea comes in through holes at the bottom, and the submarine loses its buoyancy and dives. Under water the ship is controlled by internal trimming tanks and hydroplanes. The hydroplanes, which can be seen in the lower of the two diagrams above, are external fins which can be tilted from the control-room, one pair for’ard and one pair aft; they are really horizontal rudders.

The diagram below shows the centre cross-section of a submarine diving: (1) on the surface, ballast tanks full of air; (2) starting to dive, main vents open, air escaping and sea entering the tanks; (3) fully submerged, tanks full of water, main vents now shut ready for surfacing when necessary. To surface, compressed air is released into the tanks, forcing the water out through the bottom holes.

I

MY FIRST DIVE

EARLY in 1940 the Admiralty decided to risk the experiment of introducing officers from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve into the submarine service. A request for two volunteers was sent in April to H.M.S. King Alfred, the new R.N.V.R. training establishment on the sea-front at Hove, where a search through the files discovered an officer under training who had had experience as an amateur diver. This officer immediately accepted the astonishing opportunity and, warned to secrecy, was asked to find the other volunteer. He approached a close friend of mine who had joined up at the same time as myself, and the same night, in the digs we shared, Harold confided to me his decision to volunteer. I told him he was crazy; submarines were generally considered dangerous and unpleasant, and neither of us had ever seen even the outside of one. At the same time, I was very envious, for the two volunteers were to be promoted into the special higher navigation class due to start in a few days’ time, and I would miss it. One thing I had hoped to get out of the war was a knowledge of celestial navigation.

During the break between lectures the next morning, I way-laid the Commander in charge of instruction and told him of my earnest desire to join the navigation class. He said that the class was already made up; moreover, I had not completed the regulation three weeks of elementary training. I pressed my case more urgently. At last he regarded me thoughtfully and asked my age. I told him, twenty-six. Was I married? No. Sea experience? Only week-end yachting. He then said, “Come to my office,” and I followed him down the corridor with a beating heart and the conviction that my temerity had done the trick.

Up to this point it had not entered my head to volunteer for service in submarines. It was therefore with something of a shock that, after being told to shut the door and sit down, I heard the Instructor Commander asking me whether I would consider doing that very thing. The Admiralty had only asked for two volunteers, he said, but he was prepared to put me forward as a third if I was really keen.

“You needn’t make up your mind immediately. Think it over and let me know tomorrow.”

“If I agree, does that mean I can do the navigation course?”

“It does.”

“In that case, sir, I will give you my answer now. It is Yes.”

I emerged from the interview with an uneasy stirring in my bowels. I tried to convince myself that I was doing the right, the heroic thing. But in my imagination I saw submarines as dark, cold, damp, oily and cramped, full of intricate machinery. Chances of survival at that time seemed small; death when it came would come coldly, unpleasantly; and the recent loss of the Thetis on trials in Liverpool Bay was still fresh in everyone’s memory. But it was too late now: I should never have the courage to retract.

At the end of our course at King Alfred the three of us were posted to different Hunt-class destroyers based on Scapa Flow, so that we should get a couple of months’ above-water naval experience as a background to our submarine training. But before we left for the north, at the end of May, an outing in a submarine on a day exercise was arranged for us. Through losing our way we arrived five minutes late at H.M.S. Dolphin, the submarine base in Fort Blockhouse, Gosport, and when we hurried across the narrow plank on to the saddle-tanks of the submarine Otway the Captain was leaning over the bridge, far from pleased at being kept waiting by three sub-lieutenants—and R.N.V.R. at that.

I was rather disappointed at the fragile and rattly appearance of this submarine. It was so different from the sleek, streamlined craft of my imagination. I was unaware that most of what I could see was a sort of outer shell which filled with water when the submarine dived. The whole of the long, narrow deck, and most of the bridge structure, were in fact pierced by innumerable holes, so as to allow this outer casing to flood when diving and drain away when surfacing. The pressure hull itself was barely visible above the surface of the water. As we were led for’ard and told to climb down through a round hatch into the innards of this monster, I don’t think any of us felt very happy about it.

We had gathered a few details about submarines when we were at King Alfred. We knew, for instance, that the pressure hull was roughly the shape of a long cigar, circular in section and tapering slightly towards each end. We knew that the lower half of it was occupied by trimming tanks, fuel tanks, huge electric batteries and so on. We knew that a submarine had diesel engines for driving her along on the surface and for charging her batteries, and that she changed over to her electric motors when submerged. But we were not prepared for the myriad impressions that bewildered us as we were led aft along the passage-way, past the various compartments to the wardroom. First of all, I was astonished at the size of the boat. In most places you could stand up to your full height. You had to duck your head to avoid various overhead obstructions, or when you passed through the water-tight doors, but in general you could walk about quite easily. The hull was wider than a London tube train. Another thing that surprised me, strangely enough, was the brightness of the lighting everywhere. And in the messes there were wooden bunks, and wooden cup-boards, and curtains, and pin-up girls, and tables with green baize cloths. I had not expected to find so much comfort and cosiness. But alas! what a confusion and complexity of pipes, valves, electric wiring, switches, pressure-gauges, junction-boxes, above our heads and on every side of us! How could anyone so unmechanical as myself ever hope to master it all?

In the wardroom, a snug compartment about the size of the saloon of a twelve-ton yacht and with every inch of space as cunningly used, we were handed over to a tall, good-looking sub-lieutenant who introduced himself as Jewell. He suggested we might like to go up on the bridge while we were leaving harbour. We followed him into the control-room, where our eyes boggled at the appalling concentration of levers, valves, wheels, depth-gauges and other mysterious gadgets, and then found ourselves climbing a vertical brass ladder which led up from the centre of the control-room through a hatch into the conning-tower. Here another vertical ladder took us through the upper hatch and on to the bridge. We clustered at the after end behind the periscope standards and tried to take in what was happening.

We were already going astern on the motors, emerging from Haslar Creek into the main fairway of Portsmouth’s harbour-mouth. Below us, on the casing fore and aft, the seamen, in white jerseys and bell bottoms, were stowing away the wires and ropes which had secured us to the jetty. Soon we were pointing, out to seaward and beginning to move ahead. The Captain, who seemed to be in a bad temper, perhaps because we had kept him waiting, was issuing a bewildering succession of orders. A throbbing and spluttering towards the stern told us that the diesels had started up. To starboard the walls of Fort Blockhouse slipped past us like a sliding door, opening up the familiar vista of the Solent, where I had sailed so often before the war. It was now an impressive scene of activity, full of ships of every kind. Soon we were kicking up a creamy wake that shone like snow in the morning sun.

Looking down over the bridge, we watched the sea rolling along the bulging curve of our saddle-tanks. Jewell explained that it was the air in these saddle-tanks, or main ballast tanks, that kept us on the surface; indeed, we were actually riding on air, for ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Dedication

- Contents