eBook - ePub

Peninsular Eyewitnesses

The Experience of War in Spain and Portugal 1808–1813

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many books have been written about the British struggle against Napoleon in the Peninsula. A few recent studies have given a broader view of the ebb and flow of a long war that had a shattering impact on Spain and Portugal and marked the history of all the nations involved. But none of these books has concentrated on how these momentous events were perceived and understood by the people who experienced them. Charles Esdaile has brought together a vivid selection of contemporary accounts of every aspect of the war to create a panoramic yet minutely detailed picture of those years of turmoil. The story is told through memoirs, letters and eyewitness testimony from all sides. Instead of generals and statesmen, we mostly hear from less-well-known figures - junior officers and ordinary soldiers and civilians who recorded their immediate experience of the conflict.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peninsular Eyewitnesses by Charles Esdaile in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

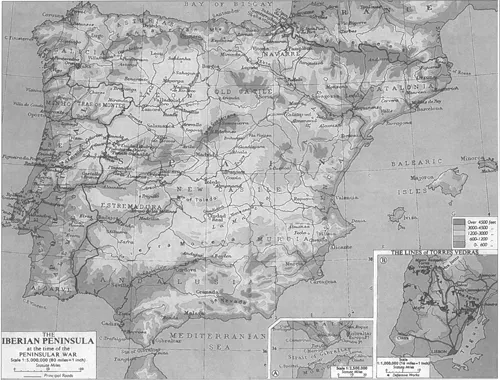

Map of the Iberian Peninsula

Preface

Dramatis Personae

Chapter 1. Iberia in Revolt

Chapter 2. The Revenge of the French

Chapter 3. Recovery and Counter-Attack

Chapter 4. Cádiz Saved; Portugal Defended

Chapter 5. Race Against Time

Chapter 6. The Turn of the Tide

Chapter 7. The Overthrow of Joseph Bonaparte

Epilogue: Some Endings

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Preface

Sitting in Madrid’s Parque del Retiro on a warm summer morning one feels a long way from the horrors of war: the sun is shining, the flowers are in bloom, the trees are a mass of green, and there is little to be heard but the song of the birds. Some 200 years ago, however, the scene would have been a very different one. A few yards to the north of where I am sitting now would have stood the bastions and palisades of the great earthen citadel which Napoleon threw up to ensure his control of the Spanish capital, while all around me would have stretched a scene of devastation. At the beginning of the Peninsular War, the Retiro had been the gardens of the royal palace and as such had been characterised by beautiful avenues, extravagant fountains and a complex system of lakes and canals. Within a few years, however, all that had gone. As an English officer brought to Madrid in 1812 remembered, ‘The gardens … were entirely neglected: the jets d’eau no longer acted, and the basins…. were entirely empty. The gardens were strewed with fragments of sculpture and mutilated statues, that of Narcissus alone remaining perfect, because it was out of the immediate reach of the destroyers. In short, the whole edifice presented the appearance of the devastations of the Goths and Vandals rather than the visit of the encouragers and protectors of the arts as the French style themselves.’1 Two hundred years on, with Spain on the brink of her celebrations of the bicentenary of the uprising against Napoleon, it is important that such memories are not forgotten. What occurred in the Iberian Peninsula between 1808 and 1814 was the most devastating struggle to have been witnessed in Europe since the Thirty Years’ War. Out of a total population of no more than 16,000,000, at least 500,000 people died and possibly many more. Add to that the military losses – those of the French alone may have amounted to as many as 500,000 men – and one is confronted by a tragedy of epic proportions. What is more it is an experience whose scars continue to mark Spain, in particular, to this day: the bitter political divisions that make the country such a troubled place are in some ways as surely the legacy of the Peninsular War as the marks of Napoleon’s cannon balls that pepper the landmark triumphal arch known as the Puerto de Alcalá.

Spain and Portugal’s struggle against Napoleon, then, is still very much a live issue. But what does this particular book have to offer the reader.? Over the past twenty-five years or more, I have written about the Peninsular War in many guises. I have studied its historiography, its campaigns and its diplomacy; I have looked at the impact it had on Spanish society and politics; I have sought to place it in the wider context of both the Napoleonic Wars and the history of Spain; I have analysed the armies which took part on either side and the irregular combatants who gave the English language the word ‘guerrilla’; and now I am even beginning to think about its archaeology But there is one aspect of the struggle that I have never looked at, and that is its humanity. Who were the men and women who peopled this extraordinary episode in Iberian history.? What were their experiences, their hopes, their fears.? And, above all, perhaps, what did they suffer? Aided by the great wealth of memoirs and other material bequeathed us by the conflict, in this book I try to answer these questions. To a certain extent this task has already been undertaken in respect of the British army, but Wellington’s soldiers were by no means the only participants in the Peninsular War, and, for all the privations and hardship which they endured, they were certainly by no means its chief victims. Though material is sometimes lacking, I have endeavoured to do my best to give a voice to those who previously have had none: the defenceless civilians who cowered under bombardment in towns such as Zaragoza and Tarragona, starved to death in the great famine of 1812 and were the universal prey of men in uniform, whether they were British, French, Spanish or Portuguese. It has been a humbling experience, and one that I have found deeply moving. To read, for example, the anguished words of a woman pleading for help the day before she, her husband and her young son were killed in a prison massacre is not a comfortable experience, while it is hard not to feel pain on coming across such stories as that of a little child of no more than two years old who was found by a police inspector in Madrid’s Calle del Carmen late one evening in 1811: abandoned by his parents or simply lost, he had been crying in the street all day and knew only that his name was Juan. To quote Wilfred Owen, in short, ‘My subject is war and the pity of war’; in addressing this theme, I have also constantly had in my mind the words of General Sherman, ‘War is hell and I intend to make it so.’

In part, then, this work is a reaction against those who have portrayed the Peninsular War simply as a catalogue of battles and campaigns in which Wellington and Castaños, Soult and Marmont, move this division here and that division there. But from all this it follows that Peninsular Eyewitnesses is also a contribution to the Napoleon debate. One may discuss the reasons why Napoleon decided to intervene in the Iberian Peninsula ad infinitum, but in the end it is impossible to absolve the emperor of responsibility for the conflict, the result being that those who continue to admire Napoleon must necessarily reflect on the scenes portrayed in this book and ask themselves whether their hero still emerges unsullied. To my mind, there is but one answer, and it is my most earnest hope that this book will in some way serve to challenge those who still see Napoleon as some great benefactor of humanity, not least because it reflects the wishes of at least some of those who were there. To quote the British brigadier Robert Long, ‘It would be curious to see a correct return of the casualties that have occurred on either side since the commencement of this sanguinary contest, and, having ascertained it, I should like to inscribe the totals in letters of blood on the walls of every room occupied by the demon who has occasioned it, though he would only grin, perhaps, with ferocious delight.’2 The correct return of the casualties called for by Long will probably never be obtained, but a variety of records allow us to recover the names of at least a selection of those lost in the conflict, and one such group – the people of the little Aragonese pueblo of Utebo (in 1808 its inhabitants numbered just 493) who died from illness and wounds in the second siege of Zaragoza – has been chosen to represent all those who would otherwise have no memorial.3

That this is not a history of the Peninsular War goes without saying. There is simply not the space to describe every encounter between the Allies and the French, and I trust that if readers want more detail they will forgive me if I refer them to my Peninsular War: a New History. At the same time, too, I am to some extent bound by the limits of what is available: there is more British material than French, more French material than Spanish, and more Spanish material than Portuguese (indeed, there is no Portuguese material at all: consultation with a variety of Lusitanian scholars has confirmed that Portugal did not produce even a single personal memoir). In a variety of ways, such factors cannot but dictate the shape of the book, while readers are also reminded of many of the problems that any author has to face when working with memoir material. What one gets is often something written many years after the event by men whose memories were distorted by the passage of time, and who had frequently been heavily influenced by reading histories of the conflict such as the one published by William Napier, who had a variety of axes to grind and who knew the value of a good story. No one, then, should be under the illusion that everything in these pages is necessarily ‘true’, and it is in fact the case that the whole issue of the ‘memorialisation’ of the Peninsular War – the process by which it was constructed as a historical memory – would be an excellent subject for some up-and-coming doctoral student. But, to return to Peninsular Eyewitnesses, the issue matters rather less than might be expected in that what is described is not so much event as experience, and in terms of memory this is something that is much more likely to stand the passage of time. This is not the end of the problems, of course – old soldiers are renowned for their tall stories – but the reader can be assured that there is nothing in these pages that is not at the very least plausible.

Another practical matter that has arisen in writing this book is the issue of language. Even in English, spelling and, especially, punctuation did not always correspond to modern forms, and for ease of reading I have had no hesitation in modernising both. As for the many passages that I have translated from French or Spanish, I have again endeavoured to render these in such a way as to make them accessible to the reader. At times this has meant reflecting the spirit of a passage rather than sticking to a literal translation, but every effort has been made to do so in a way that I felt reflected the mood and intentions of the author, and I trust that none of those involved will come back to haunt me for any errors I have committed in this respect. Very occasionally, too, a particularly rambling approach has forced the introduction of changes in the sentence order. Once again, however, this has been handled with great care, and the result has in no case altered the emphasis or meaning. Finally, there is the issue of the rendering of place names. In the original this is often erratic in the extreme, and I have for obvious reasons sought to ensure that the modern form is always used, while at the same time eliminating some of the more glaring and outdated anglicisations that litter the memoirs of Wellington’s army, in defence of which I have no hesitation in recurring to the Duke’s own insistence to his ‘exploring officers’ that place names should always be rendered accurately and in the form in use in the country concerned.

My thanks are many At Pen & Sword, Rupert Harding has been the soul of patience, while at the same time deserving credit for the idea on which this book was based. At A.M. Heath & Co. my agent. Bill Hamilton, has never ceased to give me support and encouragem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents