- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Naval War in the Baltic, 1939–1945

About this book

A military historian and naval warfare expert delivers a revealing history of the Baltic Sea Campaigns and their significance throughout WWII.

From the Battle of Westerplatte on the Polish coast in 1939 to the thousands of German refugees lost at sea in 1945, the Baltic witnessed continuous fighting throughout the Second World War. This chronicle of naval warfare in the region merges such major events as the Siege of Leningrad, the Soviet campaign against Sweden, the three wars in Finland, the Soviet liberation of the Baltic states, the German evacuation of two million people from the East, and the Soviet race westwards in 1945.

Naval historian Poul Grooss explains the political and military backgrounds of the war in this theatre while also detailing the ships, radar, artillery, mines and aircraft employed there. He also offers fascinating insights into Swedish cooperation with Nazi Germany, the Germans' use of the Baltic as a training ground for the Battle of the Atlantic, the secret weapons trials in the remote area of Peenemunde, and the Royal Air Force mining campaign that reduced the threat of German submarine technology.

A major contribution to the naval history of this era, Naval War in the Baltic demonstrates the extent to which the Baltic Sea Campaigns shaped the Second World War

From the Battle of Westerplatte on the Polish coast in 1939 to the thousands of German refugees lost at sea in 1945, the Baltic witnessed continuous fighting throughout the Second World War. This chronicle of naval warfare in the region merges such major events as the Siege of Leningrad, the Soviet campaign against Sweden, the three wars in Finland, the Soviet liberation of the Baltic states, the German evacuation of two million people from the East, and the Soviet race westwards in 1945.

Naval historian Poul Grooss explains the political and military backgrounds of the war in this theatre while also detailing the ships, radar, artillery, mines and aircraft employed there. He also offers fascinating insights into Swedish cooperation with Nazi Germany, the Germans' use of the Baltic as a training ground for the Battle of the Atlantic, the secret weapons trials in the remote area of Peenemunde, and the Royal Air Force mining campaign that reduced the threat of German submarine technology.

A major contribution to the naval history of this era, Naval War in the Baltic demonstrates the extent to which the Baltic Sea Campaigns shaped the Second World War

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Naval War in the Baltic, 1939–1945 by Poul Grooss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Baltic

Geography and History

Sea areas

The Skagerrak and the Kattegat have at times been regarded as transitional areas for the Baltic Sea – the Baltic Sea proper begins with the three Danish straits. In the Middle Ages, it was known as the Baltic Sea or the Baltic Salt; the latter name is still used in the Faroese language. In Latin, the sea was called Codan, or Mare Balticum. The North Sea in the Danish King Frederik II’s time (1559–1588) was referred to in Danish as the Western Sea, while the Baltic waters west of the Baltic states and Finland were also known in the local languages as the Western Sea.

In the eastern Baltic, there are three waterways that are partially closed or which are easy to close off against a military opponent. The first is the Gulf of Bothnia, which includes the Sea of Åland, the Bothnian Sea and the Bay of Bothnia. Next is the Gulf of Finland, which is a long, narrow area of sea between Estonia and Finland. At the eastern end of the gulf lies St Petersburg, which for many years has been Russia’s and the Soviet Union’s capital and second largest city respectively. The third area is the Gulf of Riga. The main seaward approach is via the Irben/Irbe Strait south of the southern tip of the island of Saaremaa, but you can also sail in and out through a narrow channel inside an Estonian archipelago through Muhu (Moon) Sound, which connects the Gulf of Finland to the Gulf of Riga. This brings you out to the east of Saaremaa, Hiiumaa and some smaller islands. All three areas are affected by the formation of ice, which may make it impossible to sail through from December to May. Since the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga are usually closed by ice for long periods, Russia and the Soviet Union have had a need for ice-free ports for their fleets along the Baltic coast.

After passing through the Danish straits and past the German island of Fehmarn, there are seven major islands in the Baltic Sea: Rügen, Bornholm, Öland, Gotland, Åland, Saaremaa and Hiiumaa. Near some of these islands are small islands or archipelagos. In the Sea of Åland, there are numerous islands and skerries.

Straits and canals

From ancient times, there have been three routes for sailing in and out of the Baltic Sea: the Sound (Øresund) between Denmark and Sweden; the Great Belt between the two largest Danish islands of Zealand and Funen; and the Little Belt between Funen and Jutland. In the Viking Age, ships could sail up the Schlei to Hedeby near Schleswig, where the army road went in a north– south direction. From here a cargo could be transported the short distance over land and shipped onward into the North Sea on another ship. From the Middle Ages until the Napoleonic Wars, shipping went almost exclusively through the Sound. Accurate hydrographic surveys were not taken in the Great Belt until around 1806 by the Royal Navy, as Great Britain at that time had extensive commercial and military interests in the Baltic Sea. Because of its narrow and winding course, the Little Belt has never had any special significance as an international sea route.

In the Sound, there are three passage options. On the Swedish side, there is Flinterenden (in Swedish, Flintrännan), east of Saltholm. Flinterenden was not sounded during the Great Northern War of 1700–1720, but on one occasion the Swedish navy made use of it, even though it resulted in some ships running aground. On the Danish side, west of Saltholm, there is a channel at Drogden. From the south, it splits into two northbound channels. One of them runs east of Middelgrunden (Middle Ground) and is called Hollænderdybet (Dutchman’s Deep), while the other goes west of Middelgrunden and is called Kongedybet (King’s Deep). In the eighteenth century, one of the Danish navy’s quandaries was whether they should focus on ships of the line with two battery decks which could pass through Drogden, or on those with three battery decks which could not pass through Drogden, but had to go north of Zealand and into the Baltic Sea via the more precarious route through the Great Belt.

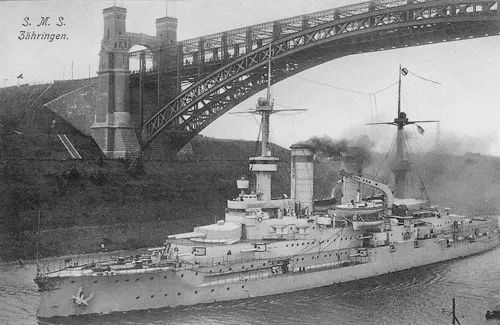

The German battleship SMS Zähringen of the Wittelsbach class in the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal.

In 1895, Germany opened the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal, today referred to as the Kiel Canal. It was built for military purposes, so that the Imperial German Navy could be sent into either the North Sea or the Baltic Sea according to military needs without being exposed during a passage, particularly in relation to the Royal Navy. The canal is 61 miles/98km long and has locks at both ends. Immediately after the canal opened, the number of shipwrecks on the west coast of Jutland fell considerably. Besides the element of risk when operating in the North Sea, the canal reduces the sailing time between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. From Kiel to Brunsbüttel, where the two locks are, there are 55 nautical miles through the canal, compared with 575 nautical miles (1 nautical mile = 1.15 land miles = 1,852m) around the Scaw (Skagen). The channel has continuously been deepened and allows the passage of ships with a draught of 33ft/10m. It was widened in the summer of 1914 so that the largest German warships could use it.

Territorial waters

Discussions about territorial waters and the high seas in the eighteenth century concluded in a general acceptance of the rights of coastal states to a distance of approximately one cannon shot from shore and this developed further into an understanding of about three nautical miles. Some countries claimed three nautical miles, others four.

Maritime territory consists of the inner and the outer territorial waters. A state can demand that outer territorial waters be respected which extend out to at most twelve nautical miles from the baseline, which is the line between the outermost points of the coastline. In a large bay, the baseline will thus follow the coast at a distance of the width of the territorial limit, while in a small bay it will follow the line between the outermost points of the bay.

In its maritime territory – underwater and in the air space above it – a coastal state has, in principle, full jurisdiction inter alia to enforce its legislation, just as it does on land, including the laying of sea mines. The coastal state must, though, observe the right of foreign ships to innocent passage in external territorial waters. Innocent passage in internal territorial waters, where the coastal state has sovereignty, may not be demanded. Special regulations apply for international straits, ie straits that connect one part of the high seas with another part of the high seas.

Danish and Norwegian territorial waters were important for the war at the beginning, while they played a decisive role in Sweden during the entire period. Sweden has claimed four nautical miles since the eighteenth century. During the First World War, the Germans violated the Swedish limit, and in 1916, a German court in Berlin ruled that Germany would respect a fishing limit of four nautical miles, but a neutrality limit of only three nautical miles. After the verdict, the Germans laid mines right up to three nautical miles of the coast near Falsterbo, but Sweden still insisted on its four nautical miles of territorial waters.

In 1933, the Soviet Union opened the White Sea Canal or Stalin Canal, a 141-mile/227km excavated canal with nineteen locks, which allows navigation between Leningrad and the White Sea via the large lakes of Ladoga and Onega. The canal is ice-bound from October to May. It was the Soviet Union’s first project to be completed by slave labour from the later infamous Gulag system. The prisoners were known as ZEK1 in prison slang. The canal is also restricted by a maximum draught, originally 16ft/5m (now 11ft/3.5m), and a lock width of 58ft/17.6m. The Russians had earlier solved this problem by, for example, mounting a larger vessel or a large submarine on a large, broad, flat-bottomed floating dock with less than 16ft/5m draught. Then the floating dock is towed through the canal system. From Lake Onega, further passage is possible along the Volga–Baltic Waterway which goes down to the Sea of Azov via the River Don and from there into the Black Sea.

Finally, it is possible to sail from Gothenburg along the Göta Canal through Sweden to the south of Stockholm, via Lakes Vänern and Vättern. However, the canal with its fifty-eight locks is only passable for small vessels with a draught of less than 9ft/2.8m and a length of up to 105ft/32m. The canal is ice-bound for four months of the year. Because of acts of war close to Swedish territory at the beginning of the Second World War, the Swedish government implemented the construction of the Falsterbo Canal so that Swedish shipping could sail along the coast within Swedish territorial waters. The Kogrund Canal served a similar purpose. If one sails east of the Kogrund Canal along Scania’s southwest coast, one can remain within Swedish territorial waters. If an enemy respected the territorial waters, one could thus sail without the risk of mines along this route.

Power struggles around the Baltic Sea – a historical perspective

The Viking Age and the Middle Ages

Excavations in the major Nordic Viking towns of Hedeby, also known as Haithabu (in Schleswig), and Birka (near Stockholm), and at other sites have revealed an extensive trade in the Viking Age from the Baltic region and further down towards the Black Sea along the many river systems. Novgorod in Russia occupied a central place in the Vikings’ trading network. From 1157, Finland was under the Swedish crown.

Cape Arkona was conquered in 1168 from the local Wendic tribes and the whole island of Rügen became a Danish fiefdom which was included in the diocese of Roskilde until 1325. During the reign of Valdemar the Conqueror in the thirteenth century, parts of current Estonia were subjected to the Danish crown. The capital was called Tallinn, which is derived from the Estonian words Taani Linn, meaning ‘Danish town’. The conquest was encouraged by the Catholic Church, which at the time was seeking to increase its power and influence eastwards. From the opposite side, the Slavic population was spreading the Greek/Russian Orthodox faith and for centuries the River Narva was the border between these two faiths. The River Narva runs from Lake Peipus northwards and flows into the Gulf of Finland. It was on the west bank of Lake Peipus in 1242 that the canonised Russian national hero Alexander Nevsky defeated the German knights.

From 1241, the Hanseatic League, and above all Lübeck, started to be an economic power in the region. It lasted for the next three hundred years. Visby on Gotland played a special role as a natural centre for the Baltic trade – Gotland was Danish from 1361 to 1645. Danzig (now the Polish town of Gdańsk) later evolved into the centre for all trade in cereals in northern Europe, and the German knightly orders and the Hanseatic League were firmly in the driving seat in this part of the economy. The power of the orders of knights began to wane in the 1550s as a result of the Reformation.

The Danish King Frederik II restored the Danish presence in Estonia in 1559 when he bought the diocese, which included Saaremaa and Hiiumaa.

Near the mouth of the River Narva lie two towns: Estonian Narva on the west side and Russian Ivangorod on the east. There is a fort belonging to each settlement. Danes, Swedes, Poles and Russians have fought in this area throughout the centuries for land, trade and ports. Narva was founded in 1222 by Valdemar the Conqueror and remained in Danish hands until Valdemar IV Atterdag’s sale of Estonia to the Teutonic Order in 1346. Among the Estonian regions, the island of Saaremaa remained in Danish hands the longest – right up to the Peace of Brömsebro in 1645.

Sound dues and power relationships in the Baltic Sea

From 1429, the Danish king extracted ‘Sound dues’ from ships that passed Kronborg at Elsinore (Helsingør). Almost all transportation of large amounts of goods over longer distances took place by ship. As maritime and trading nations, the Netherlands and England were very interested in the significant trade in the area. This gave rise to the classic problems of power and rights. Those coastal states which were strong enough wanted to enforce a principle of mare clausum, ie a closed sea, where only the coastal states were involved in the trading. The weaker powers and the intruders wanted a mare liberum, a free sea where trading was open to all. This battle for dominance of the Baltic Sea affected Danish and Swedish foreign policy and the Latin name was often used: Dominum Maris Baltici. It led to wars for hundreds of years and the Netherlands and England, in particular, used their naval power to support a policy in favour of the weak powers in the Baltic Sea. The aim was to ensure that no single nation got total dominion over the coastal reaches in the straits. The wars between Sweden and Denmark were mainly about trading rights in the Baltic Sea and all rights were based on the power that each state could put behind its demands.

Poland and Lithuania

From 1386 right up to Poland’s dissolution in 1795, Poland and Lithuania were united and at times the two countries formed a strong polity. Formally, it was the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a union in which Poland was the dominant partner. The Teutonic knightly orders were kept in check by the Polish king, who defeated them at Tannenberg in 1410; Moscow was captured and was under the domination of the union from 1610 to 1612 – the nation stretched all the way to the shores of the Black Sea at certain periods.

The Swedish wars

From about 1560 until 1660, Sweden carried out a dramatic expansion of its territories and consolidated its power in what are now Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Denmark and Norway. A large part of the Baltic coast thus fell into Swedish hands. The Swedish army was partly financed by export earnings from iron and arms. Generally speaking, the Swedish armies were very strong, but the Swedish navy was sometimes poorly led and in a worse shape than the Danish. In 1644, the Danish navy was almost wiped out by a Swedish-Dutch fleet and the subsequent Peace of Brömsebro was the beginning of the collapse of Denmark’s foreign policy. When the next war broke out, the King of Sweden came from Torun, in what is now Poland. He gathered together some scattered Swedish forces and immediately marched west. A strong Danish-Norwegian fleet could usually maintain the security of the Danish islands, but not Jutland and Scania, and when in 1658 Danish territorial waters became ice-bound, the Swedish army crossed the ice and thereby won the war. In this way, Denmark lost the provinces of Scania, Halland and Blekinge in southern Sweden, all of which had constituted an integral part of Denmark since the Viking age. The Swedish wars were very much about the right to maritime trade. Shipping paid Sound dues to the Danish king. During the Scanian War of 1675–1679, the Danish-Norwegian navy transported a large army over to Scania, but it was defeated.

Russia becomes a Baltic power

In 1558, Russia fought her way out to Narva and started trading from there. The Swedes captured Narva in 1581 and forced the Russians back from the Baltic Sea again. One of the reasons for the Great Northern War from 1700 to 1720 was a Russian desire to regain access to the Baltic Sea and thereby to the extensive trade in the area. During this war, Sweden was crushed as a great power. Because of the intervention of the great powers, Denmark did not get its lost lands back, despite a renewed attempt at reconquering Scania. Russia captured the River Neva estuary in 1703. The Baltic states were incorporated into the Tsarist Empire in 1721 and from this year, Russia became a significant power in the Baltic Sea.

The Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic wars also reached the Baltic region. In 1801, Britain had prepared a punitive action against the second League of Armed Neutrality. This consisted of the three naval powers of Russia, Sweden and Denmark, which, thanks to a joint convoy system, were earning enormous sums trading with everyone, including the warring parties. The action against Sweden and Russia was called off after the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, when it became known that the Russian Tsar Paul I h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 The Baltic: Geography and History

- 2 Political Manoeuvring Between the Wars

- 3 Naval Developments Between the Wars

- 4 The Attack on Poland

- 5 The Baltic Region After the Polish Campaign: October 1939 – June 1941

- 6 Attack on the Soviet Union: 22 June 1941 – Spring 1942

- 7 The War between Spring 1942 and Spring 1944

- 8 Towards the End: Spring 1944 – New Year 1944/1945

- 9 New Year 1944/1945 to the End of the War – Month by Month

- 10 The End of the War: Aftermath and Retrospect

- 11 Postscript

- Appendices

- Sources and Bibliography