- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

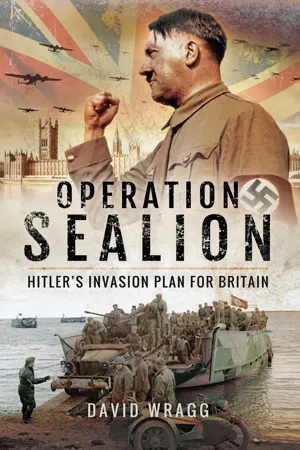

About this book

During the Summer of 1940, Hitlers Germany appeared unstoppable. The Nazis were masters of mainland Europe, in alliance with Stalins Russia and only the English Channel prevented an immediate invasion.Britain stood alone. The BEF had been routed but, due to the Dunkirk miracle, most of her manpower had returned albeit without their transport and heavy equipment and guns. There was no doubt that the Nazis planned to invade all intelligence pointed that way. In the event it never materialised, thanks to the outcome of the Battle of Britain and Hitlers decision to invade Russia.Operation SEALION examines just how realistic the German threat of invasion was. The author studies the plans, the available capability and resources, the Germans record in Norway and later Crete. The author weighs these against the state of Britains defences and the relative strengths of the land, air and particularly naval forces.The result is a fascinating study of what might or might not have been.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Operation Sealion by David Wragg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Unstoppable Hun

On the night of 15/16 September 1940, Guy Gibson, later to be the most famous of the Royal Air Force’s bomber pilots, was flying a Handley-Page Hampden bomber over the port of Antwerp in German-occupied Belgium. It was the biggest raid on the port at that early stage of the war.

‘It was the night of the full moon; many barges were sunk, many blew up, destroying others around them,’ recalled Gibson. ‘They were full of stuff and we could see, there and then, there was no doubt about it, the Germans were ready.

‘Flying low over the docks that night we could easily see the tanks on board, the guns on mountings at the stern of each invasion craft, the tarpaulins over sinister objects on the docks. “Der Tag”1 was drawing near for the Hun, and September 15th was, perhaps, the day when they realised that it would be no use.’2

What had brought the RAF to bomb barges in a Belgian port? Indeed, why were barges being gathered in northern France and Belgium?

France had fallen on 21 June, less than six weeks after the German invasion had begun after nightfall on 12 May. The evacuation of the British army, as well as many French soldiers, from Dunkirk had been completed on 3 June, leaving most of their equipment behind them.

France and the United Kingdom had declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, after Germany had ignored an Anglo-French ultimatum for Germany to withdraw from Poland, which been invaded two days earlier. It seems that the Germans did not expect the United Kingdom and France to act upon their ultimatum, indeed both the head of the German Navy, or Kriegsmarine, Erich Raeder, and his U-boat commander and eventual successor, Karl Dönitz, were taken by surprise and had to temporarily excuse themselves from meetings when the news was passed to them. After all, there had been no Anglo-French intervention during the Sudetenland crisis almost a year earlier, and a look at a map showed that neither of the two allies was well-placed to intervene in Poland, with Germany, the most populous and largest country in Western Europe, sitting firmly between France and Poland, and able to control the natural approaches to the Baltic, the Skagerrak and Kattegat.

It was not just this, for during the intervening period, Germany had completed the occupation of Czechoslovakia with little fuss. Germany had earlier, in March 1938, absorbed Austria into the Third Reich, but not without the support of many of that country’s population. Germany and what had been at the time the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been allies in the First World War. Post-war, plans to call Austria Deutschösterreichische were banned by the Allied Control Commission, determined not to see the creation of what might be called a ‘greater Germany’ from the ruins of what had been the costliest and bloodiest war in history. Nevertheless, the dream of a united German people lived on, with many yearning for an Anschluss, or ‘joining together’ of the two countries.

Germany’s ally, Italy, had also been expanding across the Adriatic into the Balkans, and, more controversially, had nearly started a European war with its invasion of Abyssinia, present day Ethiopia, in October 1935.

The British and French governments’ policy of appeasement had been highly acceptable for most of the British population. In 1939, Mass Observation, the official public opinion polling organisation, had found most people were keen to avoid war at almost any price with memories of the First World War still vivid. In Germany, the invasion of Poland was supported by many as simply being a case of Germany regaining territory lost in the First World War, when Poland’s boundaries had been extended westwards by the Treaty of Versailles. Germany did not complete the occupation of Poland until the launch of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, in summer, 1941, and in the meantime was content to allow the Soviet Union to occupy the eastern area of the country. Trade between the Soviet Union and Germany continued right up to the start of the invasion as Germany was heavily reliant on Soviet supplies of food, raw materials and, most important of all, oil. The traffic was not one way as the Soviet Union also needed German machinery and vehicles.

While much attention has rightly been given to Hitler’s demands for Lebensraum, ‘living space’, for Germany’s population, the other important factor was that Germany was heavily dependent on imports, with few natural resources other than coal. Even agriculture was only viable with massive imports of fertilizer.

Poland was invaded on the pretext of what might be described as a frontier provocation – but Poland was in no state to invade Germany. In 1939, the country was one of the most backward in Europe, with poor roads and communications, less than 100,000 lorries, and the armed forces were using obsolete equipment. The Poles fought valiantly but were overwhelmed by strong Germany forces.

It should not be assumed that the Germans were completely superior to the other countries in Europe, or their armed forces. There were serious weaknesses in the German armed forces. The air force, the Luftwaffe, was the best equipped and had been the favoured service since the Nazi take-over. Yet even the Luftwaffe lacked heavy bombers with long range and had developed as a force to operate in close coordination with fast moving ground forces, with assaults spearheaded by armoured formations, and this combination of close air support and tanks, the famous Panzers, was the basis of the concept of Blitzkrieg, ‘Lightning War’. The Luftwaffe also lacked transport aircraft to compare with the American Douglas C-47 Dakota, or Skytrain, the military development of the DC-3 airliner. The German Junkers Ju52 was an older, slower and less capable design, originally designated as a ‘bomber-transport’, but obsolete as a bomber during the Spanish Civil War, and as a transport by 1939. No less important, the absence of full-time transport squadrons and aircrew meant that the bomber training schools were raided for pilots when an airborne assault was required, interrupting training of bomber pilots while their instructors were away.

The German army, or Heer, had fast-moving Panzer units, but the supply units had not been mechanised between the wars, unlike those of the British army, and so there was an almost complete dependence on horses to pull supply wagons and field artillery. This meant that German advances were held up by the slower pace of the horses, with the tank units risking becoming isolated from infantry and artillery, while the supply of fodder for the horses was an added burden, being bulky and much more difficult to transport than fuel, and of course, much more of it was needed.

The German navy, or Kriegsmarine, ‘War Navy’, after a change ordered by Adolf Hitler from the post-Great War Reichsmarine, ‘State Navy’, lacked aircraft carriers and was short of destroyers and battleships. The so-called ‘pocket battleships’, a term coined by the British and American media for the Panzerschiffe, ‘armoured ships’, were no match for a battleship, and while their diesel engines gave them considerable range, they were much better suited to commerce raiding rather than naval battles, and slower than a contemporary battleship or cruiser. In 1939, there were plans to develop a strong U-boat arm, but at the outbreak of war there were few ocean-going submarines actually in service.

Overall, despite ambitious rearmament plans, in 1939 Germany was short of manpower for its armed forces and heavy industry, and too short of fuel and raw materials to build the armed forces that had been planned. It was just that the early opponents were much weaker in manpower terms and equipment. The delay of almost a year after the Munich Agreement and the outbreak of war had been put to good use by the British, while the French response had been hampered by nationalisation of the aircraft industry. The problem for the British was that they were already running out of money. It has been said that in 1939 ‘Britain could only afford a short war, but could only expect to win a long one’. Nevertheless, Germany was also in all practical terms bankrupt by this time, with armament plans that could not be afforded.

Germany Strikes North

Denmark was one of the countries that placed their faith in neutrality in the years after Hitler came to power. Neutral since 1815, the country had lost Schleswig and Holstein in 1864, and from this time increasingly fell under the influence of Germany, a process that accelerated after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. That Denmark was within what might be described as Germany’s sphere of influence was widely recognised not only by her neighbours, Norway and Sweden, but also by her main trading partner, the United Kingdom. Alone amongst the three Scandinavian countries, in spring 1939 Denmark accepted Germany’s offer of a non-aggression pact. Despite this, on the outbreak of war there was no attempt to interfere with Danish trading links, and up to the invasion in 1940, the country continued to trade with the United Kingdom.

A good indication of Denmark’s agricultural importance was that after the invasion, the country provided Germany with ten per cent of German consumption of butter, eggs and meat.

Denmark was neutral in the fullest sense. Pacifist policies were widely advocated, and the armed forces did not have the same public and political support as in other European countries. It was not until 1937 that new legislation led to modernisation of the armed forces. Despite this, in April 1940 the army had just 14,000 men, out of a population of 3.85 million, of whom no less than 8,000 had been conscripted during the previous two months. The small navy depended mainly on coastal defences to protect Danish waters. It had only two coastal defence vessels, one of which dated from 1906, fifteen torpedo boats, of which five dated from before 1920, and eight small submarines, with 4,000 men. Between them, these two services had just fifty aircraft, mainly obsolete.

While details of the planned German invasion were leaked to the Danish military attaché in Berlin as early as 4 April 1940, the reports were not believed initially (the head of the Abwehr, the German military intelligence and counter-intelligence organisation, Admiral Canaris had released some details intending to embarrass Hitler, against whom he had considered a coup d’état in 1938). It was not until 8 April that any attempt was made to strengthen Danish forces near the border with Germany. The next day, at 0415, German forces crossed the border against brief resistance from the army, while the navy, which had not been placed on alert, did not fire a single shot and a German troopship entered the harbour at Copenhagen unchallenged. At 0500, German paratroops attacked the unarmed fortress of Madneso, south of Zealand, and an hour later Copenhagen was occupied. At this point, the Danish government declared a ceasefire and, under protest, accepted that Germany had occupied the country. Even so, the Danish government continued to maintain that the country was neutral until as late as 29 August 1943.

Apart from its agricultural output, Denmark was important to the Germans as a stepping stone on their way to Norway, Operation Weserübung, and once that was achieved as a secure means of communication with Norway. With both countries occupied, Germany also controlled the sea approaches to the Baltic, the Skagerrak and Kattegat.

Norway was also intent on neutrality, as in the First World War, but was to prove a more difficult proposition altogether. Experience had shown that combining neutrality with being one of the world’s major merchant shipping nations was difficult, but it had worked. In union with neighbouring Sweden until 1905, Norway had become almost completely demilitarised after the First World War. Rearmament did not really begin until 1937, so that by 1939 Norway had a poorly-trained conscript army, an air force with few modern aircraft and a small navy with few modern ships. Conscription had been introduced, but at first this was just forty-four days and even as war approached was only increased to eighty-four days.

The Royal Norwegian Navy had two battleships, although very small with a ship’s company of 270 men each and an armament no larger than 8.2-inch guns, effectively the nominal armament of a heavy cruiser, and both dated from 1901, while another two ships granted the same outdated classification dated from 1898. Not surprisingly all four had been reclassified as coast defence ships. Six destroyers, of which three dated from 1936-7, and the other three from 1910-13, were of First World War size, displacing just 550 tons each. There were also twenty-two small torpedo boats and nine small submarines.

Despite the official policy of neutrality, much reliance was placed on automatic protection by British sea power. Despite this, there were Norwegian protests when a British destroyer, HMS Cossack, intercepted and boarded the German supply ship Altmark to release British merchant seamen taken prisoner after the German Panzerschiff 3 Graf Spee had sunk their ships.

Earlier, the United Kingdom and France had considered invading Norway during the Russo-Finnish War, also known as the ‘Winter War’, of 1939-40, largely to make it easier to support Finland.

Germany invaded Norway on 9 April 1940. There were two reasons for the invasion. Clearly, control of both Denmark and Norway ensured that the approaches to the Baltic remained under German control, but there was also the need to protect the vital supplies of iron ore from Sweden. As the Gulf of Bothnia froze in winter, the only all-year route for the ore from Sweden to Germany was via a Norwegian port, after a railway journey from Sweden. The fact that Norwegian airfields and ports provided the ideal bases with which to harass the Arctic convoys from Scotland and Iceland to Murmansk and Archangel was only to become a factor after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. The Anglo-French plan to invade Norway would have centred on the port of Narvik, which might have aided Finland, but more probably would have denied Germany easy access to Swedish iron ore, and no doubt this strategic material would have been of value to the two allied nations.

The day before the German invasion, the Anglo-French Supreme War Council had ordered British warships to start laying mines in Norwegian waters to force German iron ore convoys into the open sea where they would be attacked by British and French naval forces. Minor British warships were also deployed in case of any German action against Norway. It was around this time that the British Admiralty realised that the Germans had plans to invade Norway.

The Norwegian Campaign

Norway was a more difficult proposition for the Germans than Denmark, or even Poland. There was no land border, while the terrain was very difficult, with high mountains and the coastline heavily indented by numerous fjords. In April, much of the country was still covered by snow. Another factor was that the Norwegians had time to mobilise, with the king and the government escaping from Oslo, and there was time to ask the United Kingdom and France for assistance.

The problems of geography had been taken into account by the German military planners. With typical German thoroughness, troops were landed from the sea more or less simultaneously at Oslo, Kristiansand, Bergen, Trondheim and Narvik, and air-landed at Oslo and Stavanger.

As with most military operations, all did not go according to the plan. The main initial setback was the sinking by shore-based artillery of the troop transport Blücher, which was carrying the main headquarters staff.

The two allies were supportive of Norway’s request for help, and despite their armies sitting in France expecting a German attack at any time, the decision was made to send an expeditionary force to Norway. It was estimated that at least 50,000 troops would be needed to liberate the country, but little over half that number, an initial 13,000 British and Free Polish troops and 12,500 French troops, were despatched quickly, with air and naval forces.

For the allies, further problems arose. Good airfields were scarce in Norway because of the terrain, while the country was out of range of aircraft operating from bases in most of the United Kingdom, and nowhere within France was within range. Aircraft carriers initially had to be used as aircraft transports rather than as the mobile airfields which they were supposed to be, with RAF aircra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Maps

- Chapter One: The Unstoppable Hun

- Chapter Two: After Dunkirk

- Chapter Three: Lessons of Invasions Past

- Chapter Four: The Germans Prepare Their Plans

- Chapter Five: The Battle of Britain

- Chapter Six: The State of the Navies in 1940

- Chapter Seven: Woe to the Conquered – German Occupation in The East

- Chapter Eight: Woe to the Conquered – German Occupation in The West

- Chapter Nine: The Lessons of Crete

- Chapter Ten: Barbarossa and Deliverance

- Chapter Eleven: What Would German Occupation Have Meant?

- Chapter Twelve: The Lessons of Normandy

- Chapter Thirteen: Was a Negotiated Peace an Option?

- Chapter Fourteen: Could The Germans Have Invaded?

- Appendix A: The Invasion Barges

- Appendix B: Specialised Equipment

- Appendix C: New Equipment

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Endnotes

- Plate section