![]()

Chapter 1

The Founding of Singapore

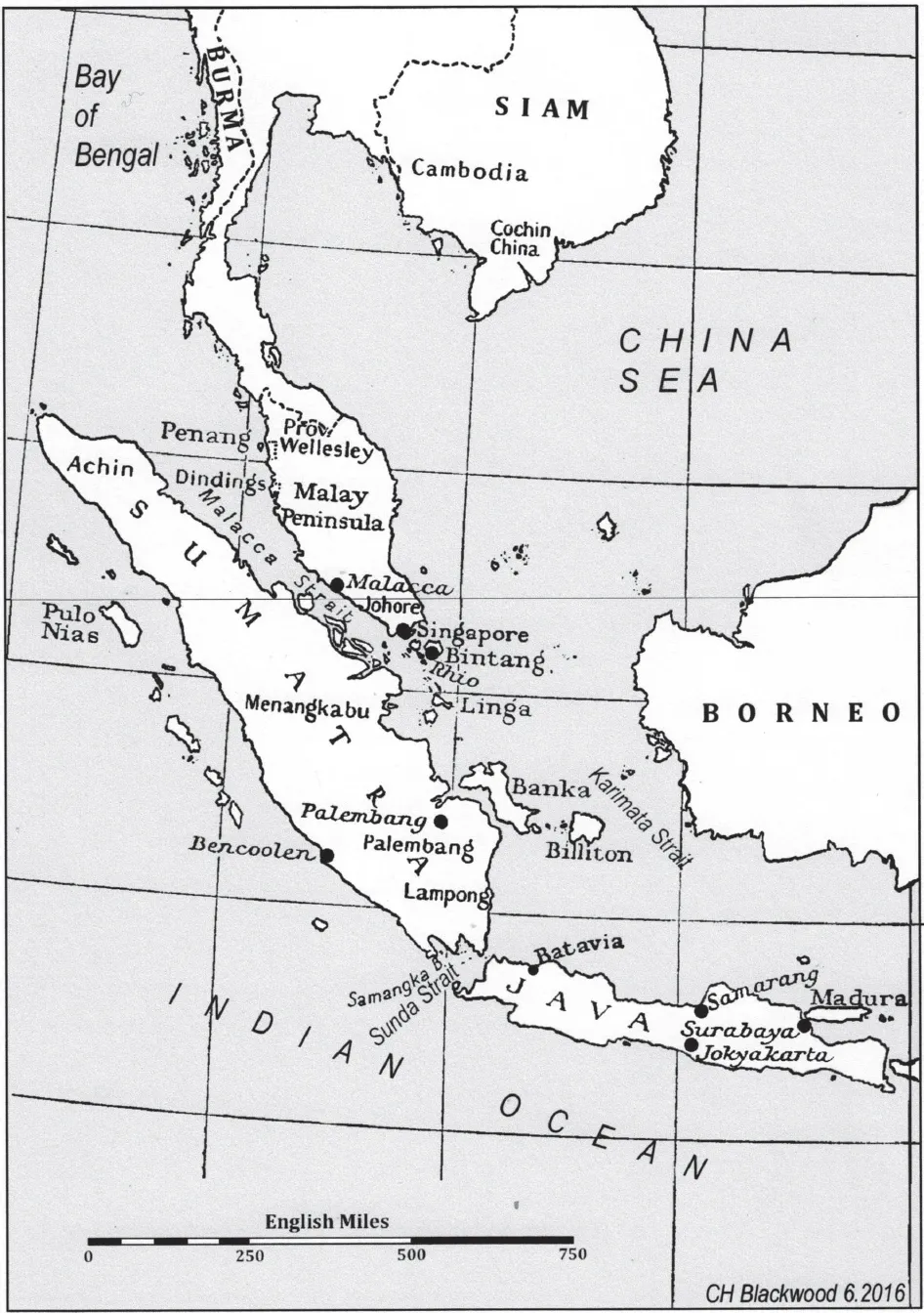

Singapore, a lozenge-shaped island, lies some 85 miles (130km) north of the Equator at the tip of the Malay Peninsula. Today the island, together with some sixty or more smaller islands and islets, forms the modern city state of the Republic of Singapore. The island is 272 square miles (716 square km) in area, and its highest natural point is Bukit Timah which stands at 545ft (166m). The main island is some 25 miles (40km) in length and 14 miles (22km) at its greatest breadth. To the north it is separated from Malaysia by the Strait of Johore and to the south from the closest Indonesian territory, the Riau Islands, by the Singapore Strait. There is a natural harbour on the south side of the island and deep water in the Strait of Johore. In addition, a line of low hills overlook what was the early nineteenth century settlement of Singapura, and these were subsequently named by the British ‘Government Hill’, ‘Mount Palmer’ and ‘Mount Faber’, this last having been named in 1846 after a Captain Charles Edward Faber of the Madras Engineers, who built a road to a signal station at the top of the hill.

Off the southern extremity of Singapore lies the island of Blakang Mati, now known as Sentosa Island, a triangular-shaped island 2½ miles (4 km) in length and 800yds (740m) in average breadth. The highest point on the island is Mount Serapong near its eastern end at about 300ft (92m). Between Blakang Mati and Singapore Island runs a channel with a minimum depth of six fathoms, forming a fine natural harbour previously known as the New Harbour. Near the eastern entrance to the New Harbour there is a smaller, irregularly shaped island, Pulau Brani, the highest point of which is approximately 170ft (52m).

In 1819, when Sir Stamford Raffles set foot on the island of Singapore, it was of little importance either commercially or strategically, and sparsely populated. Only a small population of fishermen, who were nominally under the jurisdiction of the Sultan of Riau and the local Temenggong (nobleman), inhabited the island. However, it had not always been such a quiet backwater. Known as Tumasik as early as AD 1025, it was already an independent city and port in the thirteenth century and, according to Chinese documents, repulsed a Siamese naval expedition in the early fourteenth. The island was also frequently referred to as ‘Singapura’, a Sanskrit name meaning ‘Lion City’. The fact that Tumasik had, in its day, been an important city and trading port could be seen from the remains of defences that were described by John Crawfurd, later to become Resident of Singapore.

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles by James Thomson, 1824 engraving. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Crawfurd visited Singapore in February 1822 as a member of an embassy to the Courts of Siam and Indo-China. He recorded in his journal:

I walked this morning round the walls and limits of the ancient town of Singapore, for such in reality had been the site of our modern settlement. It was bounded to the east by the sea, to the north by a wall, and to the west by a salt creek or inlet of the sea. The inclosed [sic] space is a plain, ending in a hill of considerable extent, and a hundred and fifty feet in height. The whole is a kind of triangle, of which the base is the sea-side, about a mile in length. The wall, which is about sixteen feet in breadth at its base, and at present about eight or nine feet in height, runs very near a mile from the sea-coast to the base of the hill until it meets a salt marsh. As long as it continues in the plain, it is skirted by a little rivulet running at the foot of it, and forming a kind of moat; and where it attains the elevated side of the hill, there are apparent the remains of a dry ditch. On the western side, which extends from the termination of the wall to the sea, the distance, like that of the northern side, is very near a mile. This last has the natural and strong defence of a salt marsh, overflown at high-water, and of a deep and broad creek and marsh. In the wall there were no traces of embrasures or loopholes; and neither on the sea-side, nor on that side skirted by the creek and marsh, is there any appearance whatever of artificial defences. We may conclude from these circumstances, that the works of Singapore were not intended against fire-arms, or any attack by sea; or that if the latter, the inhabitants considered themselves strong in their naval force, and, therefore, thought any other defences in that quarter superfluous.1

By 1819, however, despite its strategic location, Tumasik (Singapura) was no longer even a shadow of its former self; only a length of ruined wall and a number of carved blocks of stone, including one on which were the remains of an inscription, remained to give any indication of its former glory.

British interest in Singapore resulted directly from trade between the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) and China. Since the sixteenth century there had been rivalry between the English and Dutch over possession of the Spice Islands of modern-day Indonesia. The Dutch had been the winners in the competition for possession of these islands and, apart from temporary occupation of Batavia from 1811 to 1816, the only foothold the British retained there was the small fever-ridden outpost of Bencoolen on the south-eastern coast of the island of Sumatra.

However, the rivalry between the two nations continued, and in 1786 the British established themselves on the island of Penang, half way up the western coast of the Malay Peninsula, which they renamed Prince of Wales Island, its main port being the newly established post of Georgetown. The reason for the acquisition of Penang was to provide a staging post for HEIC ships on their way to and from China. The China tea trade was the most important business carried out by the HEIC, and the Company’s ships had, of necessity, to pass through either the Malacca Strait or the Strait of Sunda on their way to and from China. In the days of sail, voyages to China were dependent on the two annual monsoon winds, the north-east and the southwest. Captains of East Indiamen planned their outward voyage to coincide with the south-west monsoon as they rounded the tip of the Malay Peninsula which would carry them through the Strait of Malacca, then sailed back from Canton with the north-east monsoon.

As trade with China increased towards the end of the eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century, the HEIC realized that a base was needed close to the Strait of Malacca to enable their ships to replenish their stores and to counter Dutch control of the strait. The existing stations, Georgetown on Prince of Wales Island and Fort Marlborough (Bencoolen) on Sumatra, were poorly situated, and Malacca, which had been seized in 1798, although better placed geographically, was returned to the Dutch in 1816. Indeed, it was the possession by the Dutch of Malacca on the Malay Peninsula and Batavia on the island of Java that placed them in the powerful position of being able to control the strategically important Strait of Malacca and, potentially, to close the strait to HEIC vessels should they so wish.

With this as the background, Sir Stamford Raffles, the acknowledged founder of modern Singapore, appears on the scene. Raffles had started his career as a junior clerk in the HEIC in 1795 and, in 1805, through influence, was posted to Prince of Wales Island as the Assistant Secretary. He quickly proved to be an able administrator and soon became known to the Governor General in Calcutta, Lord Minto. Raffles had come to the Governor-General’s attention through his close friend John Leyden, who had arrived in Penang in 1805 and been befriended by Raffles and his wife Olivia. Leyden subsequently left Penang for Calcutta where, because of his fluency in languages, he became intimate with Lord Minto and acted as interpreter for the Governor General.

By 1811 the French had been strengthening their position in Java, which they had obtained as a result of the accession of Louis I, Napoleon’s brother, to the throne of the Netherlands in 1806. From that date the Royal Navy had been maintaining a blockade of the major ports of Java, paralyzing the French and Dutch trade between the islands and, incidentally, seriously affecting Penang’s trade. At this time Raffles, acting Secretary for Prince of Wales Island, hearing of plans for the capture of Mauritius in the Indian ocean from the French, put forward his own ideas for the capture of Java, together with a memorandum that contained all the intelligence he had obtained regarding the island and its garrison. Lord Minto approved the proposal and in 1810 passed the planning of the expedition to Raffles, who moved to Malacca, which, as we have seen, had been taken from the Dutch in 1798, and took up his appointment as Agent to the Governor General with the Malay States. There he set up his headquarters, planning to use Malacca as the springboard for an attack on Java.

The expedition to Java set sail in June 1811, and by September the island was in British hands and Raffles was proclaimed Lieutenant Governor, subordinate to the Governor General in Calcutta. Raffles was to remain in this post until 1816 when, on instructions from the Court of Directors of the HEIC in London, he was removed from the lieutenant governorship because of the increasing cost to the Company of the administration of the island which the Court blamed on Raffles. As Victoria Glendinning states in her biography of Raffles, the whole tragedy was ‘that Raffles was trying to make a first-class country out of a bankrupt one, with neither support nor investment from the Company’.2

As a sop, Raffles was confirmed in the post of Resident at Fort Marlborough (Bencoolen) in Sumatra and was permitted to take leave in England first, before arriving at Bencoolen in March 1818. Fort Marlborough, now the only British possession remaining in the East Indies, was quite a come-down for Raffles after the lieutenant governorship of Java. Originally established as a trading post, the huge fort was constructed in 1719 to protect English pepper traders. The Residency controlled some 300 miles (480km) of coastline around the fort, but this was, in fact, only a narrow strip of land that by 1818 was impoverished and declining in importance as a result of the fall in the price of pepper in London.

With the repossession of Malacca by the Dutch in 1818 under the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1814 (also known as the Convention of London), the HEIC now had need of a staging post and harbour for its ships at the eastern end of the Malacca Strait. Such a staging post would prevent interference by the Dutch with the Company’s China trade and ensure safe passage through the strait for HEIC ships. There can be little doubt that Raffles’ ambitions were considerably greater than could be encompassed by the position of Resident at Fort Marlborough, and aware of the need to establish a base that would enable HEIC ships to pass unhindered by the Dutch into the South China Sea, and also of the fact that Penang’s location could not guarantee this safe passage, he looked southwards. Believing that, strategically, the most desirable location for such a base was at or close to the narrowest part of the Malacca Strait, that is Singapore, Banka or the Riau-Lingga Islands, Raffles proposed to Calcutta that he should explore the area around the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.

Raffles assembled a small fleet of ships at Penang in January 1819 and, together with Major William Farquhar, the resident at Malacca until its recent return to the Dutch in the previous year, sailed for the Malacca Strait to discover and establish a suitable location for the new port and trading post. Raffles had to select a spot that was not currently occupied by or under the influence of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and he had previously considered a number of possible options. These included the island of Banka in the middle of the Malacca Strait which did not have any Dutch presence at that time, and also Bintang at the southernmost tip of Sumatra. However, it is possible, indeed most likely, that with Raffles’ sense of history he had already identified the ancient port of Singapura as being the most suitable location.

The eight ships of the fleet rendezvoused at the Carimon (Karimen) Islands, which are situated some 20 miles (32km) south-west of Singapore. There a survey of the main island, Great Carimon, was carried out under the direction of Major Farquhar. Although Farquhar strongly advocated the siting of the new settlement on Great Carimon, the surveyors dismissed the two possible anchorages as being unsuitable and hardly defensible. The fleet then sailed for Singapore Island and arrived there on 28 January 1819.

The sovereignty of Singapore at this time was a complicated matter. The island was a dependency of the Sultanate of Riau, the capital of which was Bintang on the island of Sumatra and which laid claim to the Riau-Lingga islands, Singapore, and Johore and Pahang on the Malay Peninsula. When Raffles and Farquhar landed at Singapore the succession to the sultanate was currently a matter of dispute, and the government of Singapore was vested in the Temenggong Abdul Rahman, one of the Sultan of Riau’s semi-royal Malay officials.

For over a century the Malay sultan had been only the titular head of state, as effective power in the sultanate had been wielded by the Bugis, immigrants whose leader was the Yamtuan Muda (Viceroy). In 1784 the Dutch drove out the Yamtuan Muda and installed a resident, only to be driven out themselves by the British in 1795. The British then reinstalled the Yamtuan Muda in Bintang. Meanwhile, the Malay sultan had established his residence on the island of Lingga, but he died in 1812 and two brothers, Tengku (Prince) Hussein and Tengku Abdul Rahman, each laid claim to the throne.

The Malay Archipelago. (Author’s collection)

The Bugis and the Dutch supported Abdul Rahman, but Hussein had the support of two senior Malay officials, both of semi-royal descent, the Temenggong and the Bendahara. The Temenggong was traditionally the third highest official in the hierarchy of the sultanate, with responsibility for ports, police and markets throughout Johore, Singapore and the nearby islands, while the Bendahara’s fiefdom was Pahang.

With the death of the Sultan Mahmud it was incumbent upon the Bendahara to appoint a new sultan but, while the appointment remained disputed, Tenku Abdul Rahman fled to Trengganu while Hussein, the Tengku Long (eldest prince), remained at Riau. So when Raffles landed on Singapore Island it was with the Temenggong that he first had to deal. The Tengku Long was summoned to Singapore and on his arrival Raffles, entirely on his own authority, installed him as the Sultan of Singapore. Raffles then signed an agreement which permitted the HEIC to establish a settlement on the island, and in return a monthly allowance was to be paid to the new sultan and the Temenggong. So it was that Singapore was established on what can only be described as a somewhat shaky legal foundation.

Raffles left Singapore after only a few days, leaving Major Farquhar as the new Resident, and Singapore officially became a dependency of Fort Marlborough rather than Penang. However, the VOC authorities were much angered by Britain’s ‘annexation’ of Singapore, which they considered to be within their sphere of influence. There were rumours of a Dutch attack on the new settlement, but this did not occur. Nevertheless, Raffles left detailed instructions regarding the construction of defences against such a possible attack, and these will be considered in the next chapter.

Raffles returned to Singapore for his second visit only four months after its founding, in May 1819, and found it already beginning to thrive, with a tenfold increase in the size of its population from 500 to almost 5,000 people. There was a proportionate increase, also, in trade and the shipping using the new port.

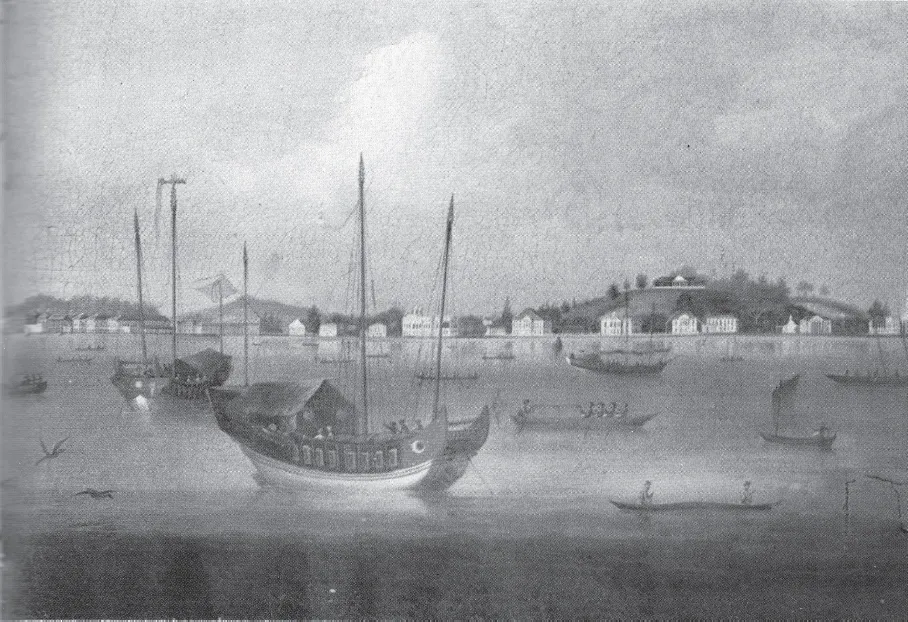

Singapore waterfront c. 1850. (Author’s collection)

For the next three and a half years Farquhar remained as Resident, only nominally under the control of Fort Marlborough, and Raffles made his final visit to the settlement when he left Bencoolen for England in September 1822. By then Si...