![]()

Contents

Foreword

Reveille

1. The Bengal Lancers

2. Early Days and Sandhurst

3. Trooping to India

4. Frontier Mail

5. Peshawar to Landi Kotal

6. Frontier Policy in Mobilization

7. Red Shirts and Afridis

8. Charge!

9. Beer, Puttees and Patronymics

10. Furlough, Fun and Polo

11. Kashmir

12. The Hog-Hunter’s Song

13. Journey’s End

14. Chasing Chickens

15. ‘Quit India!’

16. Partition

17. The Pakistan Military Academy

18. Setting Up Shop

19. Complications at Kakul

20. Two Dozen Red Roses

21. Pakistani Postscript

Last Post

Index

![]()

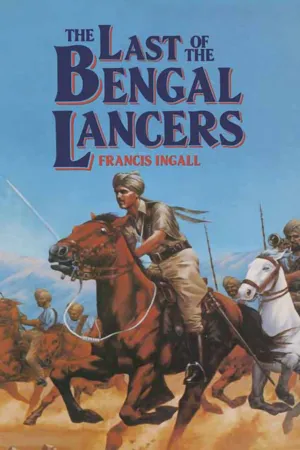

Foreword

The images of the Raj evoked in Brigadier Ingall’s memoirs will delight not only many of an earlier generation who served in British India, but also a younger audience enamoured by the grandeur and idiosyncracies of a bygone era. The author’s formidable knowledge and deep understanding of the people and their traditions enable him to write with the grace and ease borne of familiarity. In a web of tales encompassing interesting events and charming encounters, Ingall brings to life this fascinating period in the history of the sub-continent.

Ingall’s rich and varied experiences span the pre-independence era to the formative phase of Pakistan’s development when he was called upon by Jinnah to establish the Pakistan Military Academy in 1947 – an achievement for which he was awarded an OBE by King George VI. The latter part of the book focuses on the establishment of the Pakistan Military Academy which is today recognized as one of the finest institutions of its kind in the developing world.

It was while Brigadier Ingall was Commandant at the PMA (1947–1951) that I had the good fortune to have been a cadet. He inspired us with his love of independence and spirit of adventure which is so candidly reflected in his book. The Pakistan Army will always remain greatly indebted to him. The Last of the Bengal Lancers is a fine specimen of its genre and will no doubt be appreciated by all those interested in the Raj and its immediate aftermath.

(Ejaz Azim)

Ambassador of Pakistan

to the United States

9 September, 1986

![]()

Reveille

Cavalry trumpets with their flat blare have always appealed to me more than the bugle’s shrill demand.

I was sleeping peacefully in my camp cot when I was awakened by reveille sounded by the massed trumpeters of the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Bengal Lancers. As I turned over, my orderly presented me with a mug of steaming tea and some shaving water. Outside I could hear the stamping and snorting of six hundred horses, heaving themselves to their feet as their riders prepared them for the day’s action.

The regiment was encamped at Bara Fort, ten miles from Peshawar, at the edge of the Kajauri Plain. The month was October, 1930, and already the promise of the cold weather was apparent. Mist was rising from the river and there was a nip in the air. The rising sun, already tinting the swaying tops of the sugar cane, illuminated the stark tribal-occupied mountains to the west.

I shaved and washed, donned my breeches and boots and repaired outside my tent to have my khaki pagri (turban) tied around my head by my orderly.

As soon as the horses were groomed, watered and fed, the men and officers gathered for a quick meal before moving out of camp. Everyone was aware of the overall plan as the CO had briefed us all the previous evening. The officers in turn had explained our job to the sowars (troopers) and we had settled down for the night.

Such was the routine beginning of the day when first I went into battle, riding forth on my charger, sword in hand, much as my predecessors had done at the battle of Tel-el-Kebir in 1882.

![]()

1

The Bengal Lancers

What is a Bengal Lancer? To explain fully, it is necessary to go back to the beginning of the Indian Army, to the days when it was a private army, owned and paid for by the East India Company. After the Mutiny this private army became an Imperial force comprising three administrative armies in India: the Bengal Army, the Madras Army and the Bombay Army. There were also a few lesser contingents such as the Hyderabad Contingent, the Central India Horse and the Frontier Force in the Punjab.

Of the cavalry, the majority of regiments in the Bengal Army were lancers; hence they became known as ‘Bengal Lancers’. These units did not necessarily serve only in the Presidency of Bengal; they were stationed all over India. In the course of time they served all over the world.

My regiment was formed in 1857; or more correctly, the two regiments that were the ancestral units of my regiments were formed in 1857–8. These were the 13th and 16th Bengal Lancers. They changed their names and their titles several times throughout their existence. At one time the 16th was known as the 16th Bengal Cavalry; at another it was known simply as the 16th Cavalry. The 13th Bengal Lancers, on the other hand, retained that basic title throughout its history.

There is a humorous story concerning the title of the 13th. In 1882 the Regiment joined the British forces in Egypt. At the battle of Tel-el-Kebir the Egyptian Army was soundly trounced by the British. The 13th Bengal Lancers took part in a highly successful charge on that day and this action was observed by His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaught, the youngest son of Queen Victoria, who was then commanding the 1st Guards Brigade with the Expeditionary Forces. When the battle was over, he said to the Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the Regiment, ‘Colonel, I congratulate you. I am going to ask Her Majesty that I be appointed Colonel-in-Chief of your Regiment. In future, you will be known as the 13th Duke of Connaught’s Own Bengal Lancers.’ Well, the Colonel didn’t go for fancy titles at all and he thought that ‘13th Bengal Lancers’ was sufficiently distinguished for him or anybody else. He had the temerity, so history relates, to say that he didn’t wish to have his Regiment known as the Duke of Connaught’s anything!

But Her Majesty at Windsor decided otherwise; the Duke was duly appointed. On his return to India the Colonel complained to Army HQ and argued that, while he would of course accept HRH as the Colonel-in-Chief, there was no need to encumber the Regiment with a fancy title. He must have had some influence. In subsequent army lists the 13th appeared as ‘The Duke of Connaught’s’, the possessive ‘Own’ being omitted.

If the student of the history of the Indian Army is confused by royal titles it is understandable. Another regiment, the 31st Bombay Lancers, was also awarded the title of ‘Duke of Connaught’s Own’ for their part in another action at a later date, 1890. They were known as the Duke of Connaught’s Own while the 13th continued to be known as the 13th Duke of Connaught’s Bengal Lancers.

This is even more confusing to people looking through the Army List because in 1921, when the size of the British and Indian Armies was reduced, many regiments were amalgamated – including the 13th and 16th Bengal Lancers, which were thereafter known as the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers. At the same time, the 31st and 32nd Bombay Lancers were merged to form the new 13th Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers.

It was to the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers that I was gazetted in 1930. Strictly speaking, from 1921 onwards there were no longer any regiments with the name ‘Bengal’ in their title, but those lancer regiments who traced their origin to the old Bengal Army were often referred to as ‘Bengal Lancers’.

When my Regiment went to the Middle East and Europe during the Second World War, the press always referred to us as ‘a famous regiment of Bengal Lancers’. I suppose they thought they were doing the right thing as far as security was concerned, but I’m quite sure the Germans knew our full title anyway.

To return to the question: what is a Bengal Lancer? In my view, although there were many fellows who joined my own Regiment from civilian life during the Second World War, and served with distinction, they were not Bengal Lancers in the true sense of the term. In other words, when I joined my Regiment in 1930, the Regiment was horses, the sowars (troopers, enlisted men) carried lances, and the officers carried sabres and pistols. The Regiment had the same sort of organization and was doing the same sort of job as the 13th Bengal Lancers were doing when first raised in 1857. Later, of course, that changed. In 1940 the 6th Lancers was mechanized and became a light armoured regiment, reorganized and re-equipped to play a distinguished part in the Second World War.

With the passing of the horse, an era ended. The Bengal Lancer officer, mounted on his charger with sword in hand, had become an anachronism. As an officer who served in the ‘horse days’ and took part in mounted action, I can claim to be one of the last of the Bengal Lancers in the traditional sense.

How does a lancer regiment differ from other cavalry regiments? Strictly speaking, there are few differences. In a general way, all mounted units can be called cavalry and the horsed regiments of the Indian Army were referred to overall as the Indian Cavalry. This was true despite some variation in the regiments; some carried sabres while others were equipped with lances.

When I joined in 1930, there were twenty-one Indian cavalry regiments, all with different titles. There was the 1st Duke of York’s Own Lancers (Skinner’s Horse – so named for James Skinner who raised the Regiment). For a similar reason, the 2nd Royal Lancers was called Gardner’s Horse; and my own Regiment, the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers, also had a secondary title, Watson’s Horse, the 13th Bengal Lancers having been raised in 1858 by General John Watson VC.

Technically all Indian cavalry regiments were light cavalry. In the nineteenth century there were two types, light and heavy. The light cavalry were all lancers and hussars. They had lighter horses, lighter equipment, smaller men and carried a lesser load. They were the eyes of the army, performing duties that were later performed by reconnaissance units or armoured car regiments. Their primary job was not shock action, although the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava is a famous exception. Other regiments were heavy cavalry: dragoons, dragoon guards and life guards. They had bigger horses and bigger men who were armed with a heavy sabre. They were the shock troops of horsed cavalry days. All were armed with a cutting sabre in the days of Balaclava and Waterloo, but in 1910 our cavalry regiments were issued with what is known as the pointing sabre – a sword with a very sharp point at the end of a blunt blade. The idea was that you skewered your opponent as opposed to cutting his head off!

Despite – or perhaps because of – our Regiment’s lengthy title, for general purposes we were referred to as ‘6th Lancers’. On our shoulders we wore simply ‘6L’. All the enlisted men were Indian and all the officers were British. This was not necessarily the case in other cavalry regiments, some of which had a proportion of Indian officers while others were wholly Indian (I refer to Indian officers holding the King’s commission, as opposed to the Viceroy’s commission; the latter were known as warrant officers). In my day the entire complement of officers in the 6th Lancers was British. Our complement was twelve officers, but all regiments had more than that figure, because a number of officers officially borne on the strength of the regiment were absent on extra-regimental duty.

When I joined, the 6th Lancers had twenty officers on the Regimental List. One of those in extra-regimental employ was Mo Mayne who became a famous general in the Second World War – he took the surrender of the Duke of Aosta in Abyssinia, was later promoted full general and knighted. Mo, when I joined the Regiment, was a brevet lieutenant-colonel, but was shown in the Army List as squadron commander; he wasn’t even second-in-command of the Regiment, being too junior in length of service. He was away on a staff job. The authorized twelve comprised the Officer Commanding (referred to as ‘the Colonel’), the Second-in-Command, the Adjutant, the Quartermaster, and the various squadron commanders and squadron officers. Most young officers had to take a turn as Quartermaster, while the Adjutant, nominated by the CO, was considered a key appointment.

There were three Lancer Squadrons and one Headquarters Squadron. We were a ‘class composition’ Regiment – and that needs explaining.

Prior to 1857, the year of the Indian Mutiny, the soldiers of most regiments were all of one class: all Muslims or all Hindus. To incite the sepoys (Indian Soldiers) to revolt, troublemakers began to plant rumours that government-issued rifle bullets were smeared with either pig’s fat or cow’s fat. To prepare the cartridge for firing, a sepoy had to break one end of it with his teeth. Thus, a Muslim regiment was fed the story that it was pig’s fat – and the pig, of course, is anathema to any Muslim since he considered it unclean; if he eats of the pig, when he dies he goes straight to Gehenna (hell) and suffers the torment of the damned. Hindu regiments, on the other hand, were told that the cartridge was smeared with cow’s fat – and Hindus venerate the cow. The story spread rapidly through the ranks because everybody was of the same religious persuasion.

After the Mutiny, following the principle of ‘divide and rule’, the British started what they called ‘class composition’ regiments, mixing two or more different races or religions in each unit. The theory was that any unrest within one particular faction would become known to another (presumably unsympathetic) group, which would then spill the beans.

The 6th Lancers was one such composite Regiment. When I joined, one Lancer Squadron consisted of Muslims, one of Hindus and one of Sikhs; Headquarters Squadron was a conglomeration of all three. The Lancer Squadrons each had four troops of approximately thirty-five men each. Each troop was commanded by what in those days we called an ‘Indian officer’ (IO as opposed to BO), who later became known as a ‘Viceroy’s Commissioned Officer’ – a warrant officer, in fact. He did not have the powers of a British officer, and never ...