- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

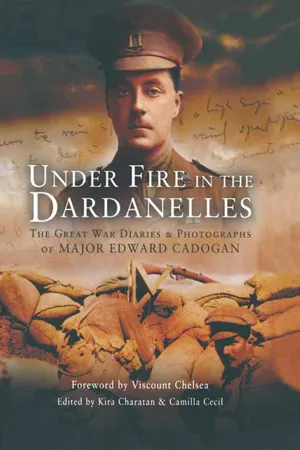

Under Fire in the Dardanelles

About this book

Edward Cadogan kept a record of his war in words and photographs. His baptism by fire in Gallipoli made a profound effect on him but, as the situation deteriorated and casualties mounted, he became highly critical of the plan and the leadership. His front line experiences are balanced by his contact with senior commanders. Wounded and clearly in poor health he was fortunate to survive. After the ignominious withdrawal, Cadogan soldiered on in Egypt and Palestine increasingly disenchanted with the conduct of the War. His descriptions of conditions at the Front are complemented by his interest in family affairs at home.This compilation is not only superb military history but a unique piece of social commentary.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Under Fire in the Dardanelles by Kira Charatan,Camilla Cecil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

| Foreword | |

| Section One | The Pre-War Months July 1914 to August 1915 |

| Section Two | Dardanelles – Gallipoli September to December 1915 |

| Section Three | Egypt & North Africa December 1915 to March 1917 |

| Section Four | Palestine April 1917 to November 1918 |

| Section Five | Postscript January to March 1919 |

| Glossary |

Foreword by

Viscount Chelsea

The diaries in this book came to light in the year 2000. My grandfather (the 7th Earl Cadogan) had recently died and so my family and I were busy moving into Snaigow, the family home in Perthshire. We were about to begin renovation work on the estate, so we were packing up anything and everything. One day, our handyman who was helping with this – Ted Downham – asked the question that now leads me to write this foreword. There are all these crates in one of the barns’, he said. ‘What do you want doing with them during the renovations?’

I was surprised; no-one had ever mentioned them to me before. I went up into the loft of the barn to see just what sort of rubbish this might be. Opening one particular, very dusty crate, I had my answer. There emerged piles of letters and bundles of paper, all neatly tied up with string.

On top was a note that said: ‘These two tin boxes contain my correspondence and documents which might be considered of interest and importance. I hope that these papers will not be destroyed without a duly qualified person examining them.’ It was signed by one E. Cadogan; so bidden by my namesake, I naturally had to look more closely.

As I started to delve into the contents of the boxes I straight away found a group of letters dated 1708–1712. They formed a correspondence between the Duke of Marlborough and the 1st Earl, who had been the Duke’s Quartermaster General. I quickly realised the significance of what I was looking at. These crates had probably not been opened for a long time.

Digging further, I soon found Uncle Eddie’s papers. (We call him ‘Uncle Eddie’ but to be precise he was my great-great-uncle Edward, my great-grandfather’s brother). They had probably been in the loft since being packed into trunks when forming part of another move, when the family came to Snaigow from Culford Hall in 1934. I doubt if they had been touched since then.

I found this connection to my namesake – another Edward Cadogan – quite poignant. It felt just as though Uncle Eddie was talking to me from the past. I sat down in that dusty, old loft in Scotland and started to read his Great War diary, painstakingly written in his meticulous hand. Four or five hours later, I emerged thoughtful into the night.

Both of us being soldiers the most powerful insight here, as I looked back at his exploits, lay in the striking similarities I found between his experience of war in the past and mine, in the present. I had been in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq during the first Gulf War and now, as I read his diaries, I discovered that Uncle Eddie had experienced many of the same thoughts, fears and aspirations in 1913 as I had before going to war 80 years later.

In my own experience, confirmed here, conflict itself feels similar too – often being 90% boredom and 10% intense fear and activity. That was certainly true in the Great War and is still the case.

After five years of transcription, cataloguing and editing, we have put together the story of Major Edward Cadogan’s war, both in pictures and in print, as a tribute to the man he was. I hope that you enjoy this diary as much as I have.

Major Edward Cadogan

1880–1962

1880–1962

July 1914 – August 1915

The Pre-War Months

Tuesday, 21st July

Today I received an invitation from Princess Beatrice to ask me to stay with her at Carrisbroke Castle. I replied, rather tongue in cheek, to her equerry that I would come if not garrisoning some east coast town.

Princess Beatrice (centre) and self (far right) during a flower show at Carrisbroke

Wednesday, 2nd July

I went to a ball at Lord Farquhar’s house in Grosvenor Square to see the King, Queen and the whole of the royal family. The next night, my father gave a large dinner party at Chelsea House in honour of Prince Lichnowsky, the German Ambassador at the Court of St James. I noticed he was questioning my father very closely and I wonder whether he was trying to find out about the Irish crisis as he must have known my father was very familiar with the Irish problem.

Chelsea House which stood on the corner of Cadogan Place and Lowndes Street

Friday, 24th July

I went down to stay with Lionel Rothschild at his place, Inchmery, on the Solent. The Buckingham Palace Conference has definitely broken down. There seems to be nothing for it but civil war in Ireland.

Saturday, 25th July

This afternoon we went out on Lionel Rothschild’s small sailing yacht. It was a dull, calm, hazy day – one of those days when you feel there is something ominous in the air – calm before the storm. I had a conversation with one of his ship’s crew who had previously served on the Meteor, the Kaiser’s great yacht. He told me the Kaiser knew nothing whatever about sailing. We returned to Lionel Rothschild’s house to find he had received a telegram from his office in the City saying that the European situation seemed easier

Monday, 27th July

I returned to London. The government seems to be endeavouring to devise some expedient to extricate itself from the consequences of the disgraceful turn of affairs in Ireland. At about 12 o’clock I was writing quietly in my room at the Speaker’s Secretary’s office when, without warning, the door burst open. Morrell, the train bearer, almost fell into my room with a report to the effect that the amending bill regarding affairs in Ireland was to be postponed.

Every moment was of importance if disaster in Ireland was to be avoided. I asked Morrell if any reason had been given. He had not heard of any so I conveyed the news to the Speaker who was seated at his writing table. He snorted and without looking up continued at his occupation. Obviously he attached little importance to the rumour. A short while afterwards he came into my room and informed me that the report was quite true, but he could not adduce any reason.

I accompanied the Speaker in procession into the House as usual. I then walked through the division lobby to the back of the chair where I found Sir William Scott Robertson, MP loitering. I asked him if he knew why the amending bill had been postponed. He replied ‘Haven’t you heard? There is a regular bombshell from Europe.’ In a few minutes we were listening to Sir Edmund Grey’s measured words, slowly realising that war might be upon us at any moment. The crisis came upon us so suddenly. Even those in authority had, until this moment, been ruefully unaware of the gravity of the situation.

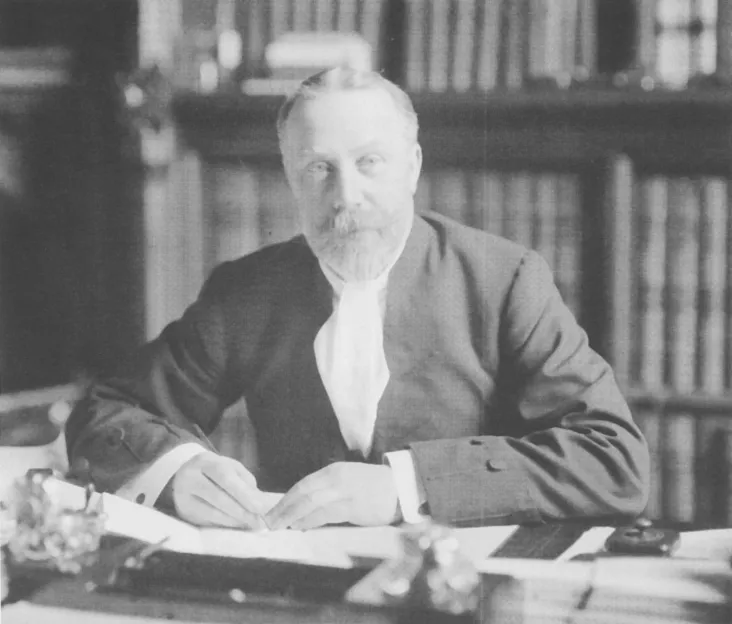

James William Lowther, 1st Viscount Ullswater (1855–1949), Speaker of the House of Commons

Saturday, 1st August

I went for a walk in the Row. War looks almost a certainty. I sat down on a seat to collect my thoughts. I had not been there long when the Prince of Wales came riding by attended by young Althorpe. They pulled up opposite to where I was and the Prince signed to me to come and speak with him. He told me that the news was serious and that a very bad telegram had been received the night before. He asked me what my brother Willie was going to do. I could only say that I was sure he would rejoin his regiment when it returned from South Africa. I then walked over to the Bachelors’ Club convinced we were in for it. I sat down at once and wrote to the Adjutant of my Yeomanry to ask him that if he was making out a list of Suffolk Yeomanry officers volunteering for active service at the front, to include my name.

In the afternoon I went down to White Lodge – a grace and favour dwelling – to stay with Lord Farquhar, who was Lord Steward to the King’s Household. I found the Farquhars and my sister all very agitated. On Sunday, Prince Arthur of Connaught had telephoned for Lord Farquhar about tea-time to say that there was bad news. The Cabinet had met and decided to remain neutral. I don’t know whether Prince Arthur was merely repeating a rumour or whether his information was from an authoritative source. If it was, then it was obvious that Asquith was convinced that he had the people with him. My brother-in-law, Sir Samuel Scott, arrived from London with grave news concerning mobilization. It was obvious now that nothing could save the situation.

Later on I went for a walk with my sister along that lovely oak avenue which is visible from the windows of White Lodge. Our conversation was solemn, consisting of predictions of what was to happen to us all in this overwhelming crisis.

Sunday, 2nd August

I returned to London with young Cecil Green, Lady Farquhar’s grandson, who was starting his examination for the Diplomatic Service that morning although he had no idea whether or not the examination would be held.

London is intense with suppressed excitement. We are always a phlegmatic people and never more so when there is good reason for being otherwise affected....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents