- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An in-depth history of naval battleship firepower from before World War I to the end of World War II, by America's leading naval analyst.

For more than half a century, the big gun was the arbiter of naval power, but it was useless if it could not hit the target fast and hard enough to prevent the enemy doing the same. Because the naval gun platform was itself in motion, finding a "firing solution" was a significant problem exacerbated when gun sizes increased, fighting ranges lengthened, and seemingly minor issues like wind velocity had to be considered. To speed up the process and eliminate human error, navies sought a reliable mechanical calculation.

This heavily illustrated book outlines for the first time in layman's terms the complex subject of fire-control, as it dominated battleship and cruiser design from before World War I to the end of the dreadnought era. Covering the directors, range-finders, and electro-mechanical computers invented to solve the problems, author Norman Friedman explains not only how the technology shaped (and was shaped by) the tactics involved, but also analyzes their effectiveness in battle. His examination of the controversy surrounding Jutland and the relative merits of competing fire-control systems draws surprising conclusions. He also reassesses many other major gun actions, such as the battles between the Royal Navy and the Bismarck, and the U.S. Navy actions in the Solomons and at Surigao Strait. All major navies are covered, and the story concludes at the end of World War II with the impact of radar.

For more than half a century, the big gun was the arbiter of naval power, but it was useless if it could not hit the target fast and hard enough to prevent the enemy doing the same. Because the naval gun platform was itself in motion, finding a "firing solution" was a significant problem exacerbated when gun sizes increased, fighting ranges lengthened, and seemingly minor issues like wind velocity had to be considered. To speed up the process and eliminate human error, navies sought a reliable mechanical calculation.

This heavily illustrated book outlines for the first time in layman's terms the complex subject of fire-control, as it dominated battleship and cruiser design from before World War I to the end of the dreadnought era. Covering the directors, range-finders, and electro-mechanical computers invented to solve the problems, author Norman Friedman explains not only how the technology shaped (and was shaped by) the tactics involved, but also analyzes their effectiveness in battle. His examination of the controversy surrounding Jutland and the relative merits of competing fire-control systems draws surprising conclusions. He also reassesses many other major gun actions, such as the battles between the Royal Navy and the Bismarck, and the U.S. Navy actions in the Solomons and at Surigao Strait. All major navies are covered, and the story concludes at the end of World War II with the impact of radar.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Naval Firepower by Norman Friedman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Gunnery Problem

The pre-dreadnought HMS Caesar (Majestic class) typified ships of the pre-fire-control era. Her fighting tops (the large round platforms on her masts) carried light automatic weapons. At the short battle ranges envisaged at this time, these weapons threatened personnel working guns in their barbettes, so earlier classes covered the barbettes with splinter-plated gunhouses. In this class the gunhouses were replaced by turrets (10.5in face, 5.5in side) because it was recognised that the rate of fire of heavy guns was now such as to threaten turret hits. The light weapons were also considered useful against torpedo craft, which had to approach to within a few hundred yards to fire. This class introduced 12in/40 wire-wound guns. In 1905–6 ships of this class had their light guns removed from the upper top forward and from the lower top aft, both being used for fire control (the foretop had a forward extension for a rangefinder, the lower maintop having a similar extension on its after end). A few ships were modified later: Majestic and Victorious in 1907–8 and Magnificent in 1908. About 1909 HMS Illustrious and others of this class showed a rangefinder in her lower forward top. Caesar spent most of World War I as Guardship and Gunnery Training Ship, first at Gibraltar, then at Bermuda (July 1915–September 1918).

HOW GOOD MUST FIRE CONTROL BE? Because its trajectory curves, a shell aimed at slightly too great a range will still hit a target extending out of the water. The allowable error is the danger space. The flatter the trajectory of the shell, the longer the danger space and thus the less precise fire control has to be. The Royal Navy 1904 trials were based on 6in gunnery at about 4,500 yards (a danger space of 100 yards): required accuracy was fifty yards and the correction after spotting was one full danger space. The longer the range of the gun, the steeper the trajectory, hence the shorter danger space. Danger space depends on the height of the target: thirty feet for the Royal Navy in 1910 (ten feet in 1904), but different for other navies and other times. Heavier guns had flatter trajectories reflected in longer danger spaces, hence greater tolerance for error. This difference became more pronounced at the longer ranges desired to avoid the torpedo threat. At 4,500 yards, the 12in/45 had a danger space of 130 feet (175 feet by 1910 rules), compared to 100 feet for the 6in. Effective hitting at longer ranges thus became associated with the heaviest guns. Hence the all-big-gun ship.

The table below, taken from 1910 gunnery figures and thirty-feet targets, gives some idea of how heavy-gun danger space changed with range1:

13.5in/45 | 12in/50 | |

Muzzle velocity | 2060 feet/sec | 2567feet/sec |

danger space at | ||

2000 yards | 348 yards | 572 yards |

4000 yards | 157 yards | 227 yards |

8000 yards | 58 yards | 75 yards |

12,000 yards | 28 yards | 33 yards |

At long ranges, the beam of the target ship (about thirty yards) exceeded the danger space defined by its height (by 1917 the US Navy, but not the Royal Navy, defined danger space in terms of both height and beam). For the British 12in/45, the crossover where shells were more likely to make deck hits was reached at 12,800 yards.2 The Imperial Japanese Navy seems to have been unique in seeking underwater hits. In effect, this increased the vertical size of the target, and thus considerably its danger space, making hits far more likely at long ranges.

Dealing with ship motion

A ship rolls from side to side, and pitches back and forth. She yaws from side to side because as she rolls her rudder seems, to the sea, to be at an angle, thus causing a partial turn. Roll, pitch, and yaw all occur at different rates: the ship corkscrews. Her guns are tilted both along and across the line of fire. The tilt across (trunnion tilt or tilt due to cross roll) changes the direction in which shells are fired (in effect, it converts elevation into sideways movement). Trunnion tilt is greatest when a ship is rolling heavily and firing more or less along her centreline, for example, when chasing another ship. Because tactics, particularly before World War I, emphasised broadside fire, initially it seemed more important to compensate for roll; yaw was more important as a complicating factor in tracking the target and measuring its course and speed. Ship motion explains why – even though guns on shore could reach thousands or even 10,000 yards – seamen at the turn of the twentieth century expected to make very few hits beyond 1000 yards.

Typically stabilising a gun moving up and down is called levelling. If the gun is pointed broadside, and the ship is rolling (not pitching), levelling is enough to cancel out ship motion. Until the 1920s it was the only kind of motion that gunners tried to cancel out. However, in most cases the gun is also rolling across the line of sight. The closer it is to being trained fore and aft, the more that the ship’s roll translates into cross-roll. Cancelling out cross-roll (or trunnion tilt or cross-tilt) is called cross-levelling.

The gunnery revolution began in 1898 when Captain (later Admiral) Percy Scott RN, then captain of the cruiser HMS Scylla, found a solution to the rolling problem. On 26 May 1899 Scylla made fifty-six hits out of seventy shots at the annual prize firing, six times her performance the previous year. This result was so remarkable that few believed it before they had seen it in action. Just as important, Scott’s guns could hit at longer ranges because they were so much steadier. Scott had carefully observed gunners, some of whom achieved great success by continuously elevating and depressing their guns so that they were always on target. Scott called this technique continuous aim. It was no longer necessary to choose a point in the ship’s roll at which to fire. Waiting for the gun-sights to come ‘onto’ the target had always been a source of error, because no gunner’s reflexes were instantaneous. Moreover, firing only at a set point in the roll limited the firing rate.

Scott was stabilising guns in the line of sight but not across it (ie against cross-roll). This pre-World War I gunnery revolution extended line-of-sight compensation to heavy guns so that, by 1914, gunners firing at 10,000 yards could make many more hits than they might have at 1000 yards before Scott. Cross-roll, however, was a different proposition.

Scott’s technique changed the roles of those controlling the guns. In the past, laying the gun (elevating it) had meant setting it at a fixed elevation for the ordered range. Now the gunlayer, who kept the gun on target, had the key role. Because he could tell whether the gun was on target, he was the one who fired. Scott introduced a separate sight-setter to enter the required elevation. As before, pointers or trainers pointed the gun on the appropriate bearing (the US Navy called the pre-Scott technique pointer firing because pointers had been more important than layers).

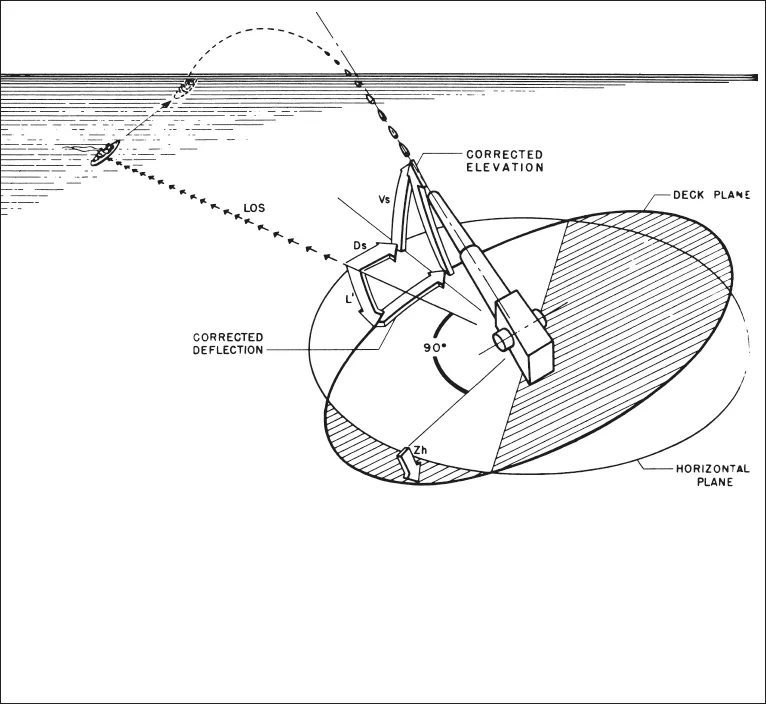

Before World War I the rolling ship motion that gunners tried to cancel out moved the gun barrel almost directly up and down, as it pointed along the broadside. Guns pointing closer to fore and aft were affected by trunnion tilt, the effect of which is shown in this diagram from the 1950 edition of the US Navy’s gunnery manual. The US Navy called the effect cross-roll, and the fixed stable vertical (Mk 32) introduced in the 1930s made it possible for a ship to fire at a selected point in the cross-roll. By World War II remote power control made it possible for guns to move to cancel out cross-roll altogether. This diagram shows the effect of trunnion tilt and the sort of corrections needed to deal with it. LOS is the line of sight to the target, the line in which a director not corrected for cross-level would point a gun. The gun is mounted in the deck plane, and it is aimed with respect to that plane, but fire control is calculated for a horizontal (non-rolling and -pitching) plane. Until after World War I, navies assumed, in effect, that guns would be fired on the broadside, and that correction had to deal only with the rolling motion of the ship that in effect elevated and depressed them. World War I showed that ships would often fire close to the fore and aft line, so that trunnion tilt might be just as important as the up and down movement of the line of sight. Dealing with trunnion tilt required correction in both train and elevation, but train was the more important error.

Scott replaced the earlier method of trying to fire when the gun reached a set point in the ship’s roll. The ship was momentarily at rest at the top and bottom of a roll. It moved fastest at mid-roll, but that speed (up or down) was more or less constant for a time. Although many gunners advocated firing at the top or bottom of a roll, it was not always easy to sense that this end of the roll was approaching, and it was very easy to miss such moments. Some ships made that easier, because they had a steady, predictable roll. Training helped ensure that gunners who sensed that the ship was approaching one end of the roll could move quickly enough for their guns to fire at the right moment (or at least close enough to it). However, if the ship was rolling irregularly, it was quite difficult even to sense the approach to the top or bottom of a roll.3 There was, moreover, a noticeable lag between the decision to fire and the moment when a shell left the muzzle. This was partly due to the time it took a gunner to fire once he had decided to do so, but it was also due to the time taken for a powder charge to ignite, and for the projectile to run down the barrel of the gun. During that time, the vertical motion of the gun would be imparted to the shell. Experienced gunners in Nelson’s time, for example, used the rolling motion to pitch their balls into an enemy’s rigging or against his waterline when the point of aim was on their side.

In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars there were attempts to use a pendulum to detect the appropriate firing point in the ship’s roll. The pendulum defined a direction in the earth, and did not require observation of the target or the horizon.4 In effect this was the beginning of an alternative to Scott’s technique, better suited to more massive weapons. The twentieth-century equivalent to the pendulum was a gyro, which tries to maintain its direction in space (not even with reference to the earth). That it should behave so completely against intuition is due to some deep facts of physics.5 A gyro defined a direction, and thus could fire a gun at a set point in a ship’s roll, even if the horizon was invisible. The first patent for a continuously running gyro suited to gunnery was taken out in 1906. The first applications to gunnery were gyro-compasses, which could cancel out a ship’s yawing motion while tracking target bearing. The first was patented in 1908. It proved more difficult to use a gyro to define a vertical, which could be used even when the horizon was invisible. Such gyros were precessional, and at least until World War II they had to be corrected periodically by reference to the horizon. Gyros were later the basis for the inertial guidance systems that made long-range ballistic missiles so fearsome: they could sense where they were, without referring to anything external such as the surface of the earth.

The upper limit for continuous aim seemed to be 9.2in calibre (under Scott’s command the cruiser HMS Terrible doubled the hitting rate for 9.2in guns and more than tripled it for 6in guns). Thus it seemed that fast-firing, medium-calibre guns could outrange heavy guns. They might not be able to penetrate the thickest belt armour, but their high-explosive shells could tear up a ship’s side and upperworks, which might be enough to neutralise her. The capital ship of the future might be a fast cruiser. To some extent this was the germ of the battlecruiser idea.

If Scott could make medium guns so effective, what could be done with heavier ones? The potential prize was enormous. Each 12in shell was four or five times as destructive as a 6in shell, and it was more likely to hit at longer ranges due to its flatter trajectory. Because these guns could not be aimed continuously, the Royal Navy sought new methods of firing and gun direction. It also experimented with more and more responsive hydraulic machinery to manoeuvre the guns, the hope being that eventually they could be continuously aimed.6

In July 1907 Captain John Jellicoe, the outgoing DNO, reported that new hydraulic engines made it possible to ‘hunt the roll’, ie, to achieve continuous aim in elevation.7 In his 1908–9 Estimates Admiral Fisher announced that such gear was being fitted to all Briti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Note on units of measurement

- Note on abbreviations

- Author’s acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Gunnery Problem

- Chapter 2: Range-keeping

- Chapter 3: Shooting and Hitting

- Chapter 4: Tactics 1904–14

- Chapter 5: The Surprises of War 1914–18

- Chapter 6: Between the Wars

- Chapter 7: The Second World War

- Chapter 8: The German Navy

- Chapter 9: The US Navy

- Chapter 10: The US Navy at War

- Chapter 11: The Imperial Japanese Navy

- Chapter 12: The French Navy

- Chapter 13: The Italian Navy

- Chapter 14: The Russian and Soviet Navies

- Appendix: Propellants, Guns, Shells and Armour

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography