- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

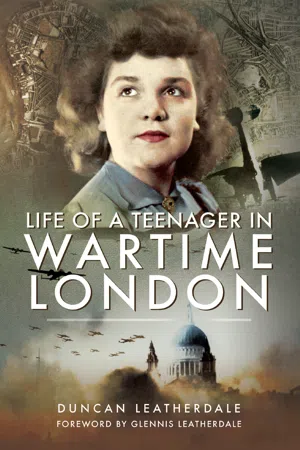

Life of a Teenager in Wartime London

About this book

Life in wartime London evokes images of the Blitz, of air-raid shelters and rationing, of billeted soldiers and evacuated children. These are familiar, collective memories of what life was like in wartime London, yet there remains an often neglected area of our social history: what was life like for teenagers and young people living in London during the Second World War?While children were evacuated and many of their friends and family went to fight, there were many who stayed at home despite the daily threat of air raids and invasion. How did those left behind live, work and play in the nation's capital between 1939 and 1945? Using the diary entries of nineteen-year-old trainee physiotherapist Glennis 'Bunty' Leatherdale, along with other contemporary accounts, Life of a Teenager in Wartime London is a window into the life of a young person finding their way in the world. It shows how young people can cope no matter the dangers they face, be it from bombs or boys, dances or death.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

London Life

In the summer of 1939, London was the largest city in the world. With more than 8.6 million residents, the capital city was home to almost twenty per cent of the nation’s citizens. It was not until January 2015 that London could once again be called home by so many.

With world-famous parks, museums, hotels, shops, theatres and palaces, it was an exciting place to live. It was, however, also to become one of the main targets for the Luftwaffe’s bombing raids, along with industrial hubs such as Liverpool, Coventry and Plymouth. The first German air-raiders came in July 1940, aiming for industrial and military targets. Two months later the most intense period of bombing began. The Blitz, as it became known, was the term also used to describe air raids across Britain and Europe. London was not the only place to be blitzed.

Initially, the bombing of London was a mistake. Hitler had ordered that bombing be kept to industrial and military targets, but on 24 August 1940, so the story goes, Luftwaffe pilots got lost and mistakenly dropped their deadly loads on central London, igniting huge fires in the East End. The RAF retaliated by attacking Berlin directly, an offensive which Hitler had assured the German people would not be allowed to happen. In response, the Germans changed tack. The citizens and streets of London and her sister cities became the targets, as much as factories, military posts and airfields had already been.

On Saturday, 7 September 1940, the Blitz began in earnest. It had, according to Angus Calder in The People’s War: Britain 1939–1945, been a ‘splendid, beautiful summer day’ spent by many sipping tea in their gardens. At about five o’clock in the afternoon, several hundred German bombers arrived to set fire to London’s docks. Wave upon wave of bombers kept coming over the next eleven-and-a-half hours, setting the East End alight. This was the first Battle of London, a fight between civilians and incendiary devices.

‘Where the bombs fell heroes would spring up by accident’, wrote Angus Calder of the men and women who leaped into action to extinguish incendiary bombs before they erupted into far more ferocious and fatal fires. Some 431 people were killed, a further 1,600 injured, and countless more left homeless on that first night.

During the night, the code word ‘Cromwell’ was issued to the Home Guard around the country, who knew then that they had to be prepared for an imminent invasion. Some even mistakenly rang the bells at their village churches, believing that the invasion was actually happening. Ringing of the bells was only supposed to occur once German paratroopers were actually seen in the air, descending on their targets.

The Germans lost forty-one aircraft that night, which was a significant number for a Luftwaffe that had been depleted by losses in the Battle of Britain air combat three months earlier. The British saw forty-four of their fighters planes destroyed and seventeen pilots killed during the first night of the Blitz. But their valiant efforts to repel the raiders over the following nights and days, during which many were forced to drop their bombs well before they reached the target areas, caused Hitler to postpone his imminent invasion plans.

Between 7 September 1940 and 21 May 1941, some 20,000 tons of highexplosive bombs were dropped on London, as well as on sixteen other British towns and cities. London was attacked seventy-one times, including on fifty-seven consecutive nights. About one million buildings were destroyed and 20,000 people, the vast majority civilians, killed.

Life on the ground, however, continued as Bunty’s diaries attest, although there were some big changes the hardy Londoners had to get used to. For a start, there was the blackout that applied to everyone everywhere in the country. Knowing that war was coming, the government announced nationwide, compulsory blackout measures starting on 1 September 1939, two days before Neville Chamberlain’s declaration-of-war speech.

During the hours of darkness, it was illegal to show a light lest you reveal a target for the aerial raiders. Blackout was stringently enforced, with fines for those who failed to adhere to it. Even just showing a chink of light could lead to a visit from the ARP wardens or police. Cries of ‘put out that light!’ echoed around the darkened streets. The start and finishing times for each night’s blackout were published in the newspapers, so the courts offered little leniency to those who claimed ignorance, with jail terms of up to three months and fines of £100 at their disposal. Even lighting a cigarette outside was forbidden. In 1940, there were some 300,000 people charged with blackout offences across the country.

The government issued plenty of advice to householders on adhering to the blackout. One Board of Trade pamphlet, released under the ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign, offered the following notes on how to best look after blackout curtains:

Never wash blackout material – washing makes it more apt to let the light through. Instead, go over your curtains regularly with a vacuum cleaner if you have one; if not take them down at least twice a year, shake gently and brush well. Then iron them thoroughly – this makes them more light proof and also kills any moth eggs or grubs which may be in them.

The blackout was something of a health and safety nightmare. Incidents included tripping over steps, walking into sandbags, falling into canals, stepping off a train platform, and, as Angus Calder describes it, ‘cannonading off a fat pedestrian’. American journalist Quentin Reynolds, in The Wounded Don’t Cry, wrote:

London is a ghost town at night. You never meet anyone on the street. Now and then the fire engines or ambulances would roar by – you never see them as they carry only the smallest sidelights. The street crossings bother you at night. You never know when you’ve reached the kerb. Then you constantly bump into lamp-posts or pillar-boxes. Walking round London at night hardly comes under the head of good clean fun.

The first incident of a person dying on the home front as a direct consequence of the war, occurred on the first night of the blackout. A police officer, who had climbed up a drainpipe to reach an illegally illuminated window to chasten the guilty party, fell three storeys to his death. By December 1939, there were an average of forty fatal accidents a day, involving pedestrians and vehicles, an eight-fold increase on pre-war numbers. It is impossible to say these were all due to the blackout, but there was little doubt that having people and vehicles mixing in the dark could only lead to bad results for the people. Eight soldiers were severely injured on 31 October when a lorry drove into the back of them as they were marching during the blackout.

Some started to question the worth of the blackout when it was leading to so many casualties. One letter writer to The Times in November 1939 said:

The chief reason for the present drastic restrictions on vehicular and street lighting is, I presume, to prevent loss of human life in air-raids; but it may be gravely doubted if the deaths by such means would, in two months, have resulted in this holocaust caused by the blackout.

Many though, appreciated the need for total darkness, and although the Air Raid Precaution (ARP) wardens, who enforced the blackout, were perhaps unpopular, they were seen as a necessary annoyance. Another correspondent to The Times even offered the wardens the use of his rooftop garden so offenders showing lights at high-up windows, which were difficult to see from the street, could be detected and disciplined.

Kerbs and other street furniture were painted white to offer some orientation at night, while pedestrians were encouraged to wear white bands or buttons, or carry newspapers to mark them out to drivers. Posters were put up advising motorists how to best prepare their vehicles. Headlights on cars and vehicles had to be masked so that only a small crescent of light was beamed on to the road, while side lamps and rear lights were to be dimmed. Only one eighth of an inch of indicator was allowed to be seen, and all dashboard lights had to be covered. This made it quite tricky for nighttime drivers to know if they were keeping to the newly imposed 20 mph speed limit.

Drivers tended to stick closely to the white line down the middle of the road, which caused more than a few head-on collisions. The Autocar magazine, which was launched in 1895 and is still being published weekly, even mooted going French and driving on the right so motorists could follow the white-painted kerb, but their suggestion never gained momentum.

Drivers also had to paint parts of their cars white, such as the bumpers, running boards and mudguards. They could be prosecuted if the painted areas became dirty. It was also illegal to park facing oncoming traffic. Some also hung large pieces of cards at each end to try and make their vehicle more conspicuous to other street users.

Car accidents soared as a result of the lack of light. Within a few months, it was estimated that about one in five people had suffered some sort of injury as a result of the blackout, be it being struck by a car or tripping over an unseen obstacle. While it was a dangerous time to be out, some relished the blackout for the cover it provided for nefarious doings. The number of assaults carried out under the protection of darkness rose. The streets were not always a safe place to be, especially for young women who may find themselves the victims of unwanted and sometimes forceful attention.

After a few months, the government did relax the rules slightly in a bid to curb the number of injuries. For example, people were allowed to carry torches as long as the beam was damped with tissue paper. When the airraid siren sounded, however, this action was again banned. The frustrating truth was, however, that even with the city’s lights blacked out, German bombers could still find their way around London on bright nights thanks to the River Thames that wound its way through it. Quentin Reynolds in The Wounded Don’t Cry wrote:

We curse bright nights when the moon is full. On a night like this, the Thames would be a white ribbon of milk pointing towards London. You can’t blackout the Thames, and the Thames tells the German bombers everything they want to know about London.

The blackout finally ended on 17 September 1944, when the threat of aerial raids had seemingly diminished. London was still attacked, however, but no longer by the manned bombers of the Blitz. A new threat arrived – the pilotless V-1 launched from mainland Europe towards Great Britain. When the engine stopped, the flying bomb dropped, causing huge destruction wherever it fell. The general rule was that as long as you could hear it, you were safe, but once it fell silent, you knew it was coming down. This was the danger of the ‘Doodlebug’, the nickname given these rockets.

The first V-1 fell in east London early in the morning of 13 June. It was reported that the explosive power of a V-1 was the equivalent of a one-ton bomb, and that whole streets could be obliterated by just one missile. London was the target of a German regime in the last throes of war. It is estimated that ninety-two per cent of V-1 casualties were in the capital. The threat was decreasing by September, as Allied forces seized the European launch sites, but a new menace was looming – the V-2. The V-2 was bigger and more powerful than its older brother, but its attacks were more sporadic. When it found its target, the V-2 was monstrous. Londoner Myrtle Solomon, in Forgotten Voices of the Second World War wrote:

The Doodlebugs were pretty frightening but the V-2s were terrifying. Perhaps we were tired by that point in the war but we were much more scared than when the bombs were raining down on us during the Blitz. I was longing for the end by then.

About 160 people were killed and many more buried in rubble when one hit a shop in South East London in November. Initially, to avoid causing public panic or letting the enemy know their unmanned bombs were finding their targets, the government refused to admit that the missiles existed. The damage they caused was instead attributed to domestic failures such as explosions of gas mains. Again, as the Germans were being vanquished, the number of rockets being fired at London declined, and eventually disappeared. Throughout the bombings by both the Luftwaffe and the V rockets, the people of London still went out to restaurants, cinemas, bars and theatres.

One threat that thankfully failed to materialise was the dreaded gas attacks. The First World War had shown the horrors that toxic gas could cause. In the months leading up to the Second World War, it was feared that such chemical weaponry would be used against Britain’s civilians. In the months leading up to the anticipated, and feared unavoidable war, the government issued gas masks to every man, woman and child in the country, some thirty-eight million in total. People were urged, as best possible, to make their homes airtight against gas. Cracks and keyholes needed filling, and were often pasted over with newspaper, while doorframes were smothered in blankets. Yellow gas-detection paint was applied to the top of post boxes, which would change colour in the event of a gas attack. People could be fined if they were found out of the house without a gas mask on them.

Naturally, the more fashion conscious found a way to carry their masks in large bags, thereby maintaining their stylish looks. Some fashion firms even released special ranges of gas-mask carriers that came with matching handbags and purses. Just as with their enforcement of the blackout, however, the ARP wardens who made sure people were carrying their gas masks irked readers of The Times.

The Home Office issued guidelines saying people should have their gas masks with them if they were going at least seven minutes away from their home or workplace. One Ronald Woodham wrote to the paper and said:

I live less than two minutes’ distance from my place of work, I am expected by the local wardens to carry my mask at all times. Here is yet another instance of that excess of zeal on the part of the local ARP workers which is rapidly making the nation a laughing-stock.

The wardens were responsible, however, for alerting civilians to a gas attack through the use of a large wooden rattle. As it turned out, gas was not one of Hitler’s chosen weapons, but the government wanted the people to be prepared.

Preparations also included offering people places of shelter from the anticipated avalanche of bombs expected to fall on their heads. Many, like Bunty’s father, chose to fortify their basements and cellars as a haven for when the bombs fell. Others built Anderson shelters in their back gardens – small, self-assembly, metal shelters partly dug into the earth. These were issued free to households that earned £250 or less a year, but it cost £7 to those who earned more. The shelter comprised of plates of galvanised steel erected over a pit dug into the earth. They offered protection from flying debris but could do little in the event of a direct hit.

In 1941, the Morrison shelter came into circulation. It was essentially a large steel cage that could be built inside the home. This meant that people could at least stay in the relative warm during air raids. Its solid top meant the shelter was often used as a table. The Morrison shelter was designed to withstand the weight of an upper floor of a house falling on it and, like the Anderson, was a self-assembly job. It was free to households who earned less than £350 a year.

Some chose not have a shelter at all. Jonathan Sweetland, a youngster living with his parents in Camden, said neither his mother nor his father wanted one. He wrote in his memoirs, held by the Imperial War Museum, that they would instead spend nights trying in vain to sleep beneath the dining room table, the noise of bombs falling, buildings being struck, guns and planes making sleep all but impossible. He wrote:

We just lay there with the cacophony of the planes, bombs and guns about us, feeling the building sway when a bomb fell close and watching the chandelier become more of a pendulum as it swung back and forth with the building.

They were fully clothed and ready to flee at a moment’s notice. In a small tin box held by his mother, were kept the most valuable family papers as well as some cash.

Many other Londoners went to public shelters while large numbers used the underground, which first opened in 1863 to allow people to travel around the city without getting their heads wet. The government was initially reluctant to let people seek shelter in the underground network for health and safety reasons. There were fears about hygiene. The inadequacy of the toilets were given as just one example of why having so many people staying in the underground stations would pose a problem. The authorities had also earmarked the underground tunnels as storage space for the hundreds of thousands of bodies they feared would result from the German air raids. The public persisted, however, and in September 1940, the government took active steps to make the underground an official shelter. ‘They were dry, warm, well-lit and the raids were inaudible’, wrote Angus Calder in The People’s War.

Some fifteen miles of platforms and tracks at seventy-nine stations were used as shelters. The record occupancy for one night was 177,000 in September 1940, soon after the commencement of the Blitz. One stretch of uncompleted track, starting at Liverpool Street and running beneath the East End, became a refuge for 10,000 Londoners. As there was no need to get out of the way of trains, there are reports of some people spending several weeks at a time down there.

Most of the stations used as shelters were also still running train services, creating a situation where some were trying to sleep or simply hold onto their spot, while others were stepping around or over them trying to board the trains. In her diary, Bunty vividly recalls making her way between sleeping people on the platforms the morning after a raid as she travelled to work. Diplomat and author Harold Nicholson, who was married to poet Vita Sackville-West, recorded in his diary on 1 March 1944, his dislike of seeing people in such uncomfortable conditions:

It is sad to see so many people sleeping on the tube platforms. It is more disgraceful tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One London Life

- Chapter Two Education and Evacuation

- Chapter Three Working Through the War

- Chapter Four The Reality of Air Raids

- Chapter Five How to Have Fun in Wartime London

- Chapter Six Wartime Holidays In and Around the Capital City

- Chapter Seven Fashion on the Ration

- Chapter Eight Making a Meal of Things

- Chapter Nine Getting From A to B

- Chapter Ten Censorship and Sensitivity

- Chapter Eleven Troubles of a Wartime Teenager

- Chapter Twelve Who was Bunty?

- Chapter Thirteen Bunty’s Wartime Diary

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Plate section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Life of a Teenager in Wartime London by Duncan Leatherdale,Glennis Leatherdale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.