- 179 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle of Jutland

About this book

The Battle of Jutland: At the end of May 1916, a chance encounter with Admiral Hipper's battlecruisers has enabled Beatty to lead the German Battle Fleet into the jaws of Jellicoe's greatly superior force, but darkness had allowed Admiral Scheer to extricate his ships from a potentially disastrous situation. Though inconclusive, at the Battle of Jutland the German Fleet suffered so much damage that it made no further attempt to challenge the Grand Fleet, and the British blockade remained unbroken. Captain Bennett has used sources previously unavailable to historians in his reconstruction of this controversial battle, including the papers of Vice-Admiral Harper explaining why his official record of the battle was not published until 1927, and the secret "Naval Staff Appreciation" of 1922 whose criticism were so scathing that it was never issued to the Fleet. Also included are numerous battle plans, photographs and an introduction by Bennett's son. 2006 is the 90th anniversary of the battle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of Jutland by Geoffrey Bennett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

| THE ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| DIAGRAMS | ||

| 1 | Genesis | |

| 2 | The Long Vigil | |

| 3 | ‘Der Tag!’ | |

| 4 | ‘Equal Speed Charlie London’ | |

| 5 | Night | |

| 6 | Who Won? | |

| APPENDIX I: THE BRITISH GRAND FLEET AT JUTLAND | ||

| APPENDIX II. THE GERMAN HIGH SEAS FLEET AT THE SKAGERRAK | ||

| APPENDIX III. THE HARPER RECORD | ||

| SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY | ||

| INDEX |

THE ILLUSTRATIONS

| Figure | |

| 1 | Commander-in-Chief of the British Grand Fleet: Admiral Sir John Jellicoe |

| 2 | ‘Fear God and Dread Nought’: Vice-Admiral Sir John Fisher, in 1897 |

| 3 | Creator of the German High Seas Fleet: Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz |

| 4 | Rear-Admiral Franz von Hipper, Leader of the German Scouting Force |

| 5 | Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, Commander-in-Chief of the German High Seas Fleet |

| 6 | The eyes of the Grand Fleet: Commodore W. E, Good-enough |

| 7 | Commander of the British Battlecruiser Fleet: Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty |

| 8 | British battlecruisers in the North Sea: Queen Maty, Princess Royal and Lion |

| 9 | The first aircraft carrier to take part in a major naval action: H.M.S. Engadine |

| 10 | A typical British destroyer of the First World War |

| 11 | Flagship of the Second Light Cruiser Squadron: H.M.S. Southampton |

| 12 | The Lion is hit on ‘Q’ turret (amidships) |

| 13 | The British battlecruiser Queen Mary is destroyed by a salvo of heavy shell |

| 14 | Flagship of the Fifth Battle Squadron: H.M.S. Barham in Scapa Flow |

| 15 | Sunk at Jutland: the British armoured cruiser Black Prince |

| 16 | The deed for which Boy John Comwell (aged 16), of H.M.S. Chester, was awarded the Victoria Cross (From the painting by Sir Frank Salisbury) |

| 17 | The midship magazines of the British battlecruiser Invincible explode |

| 18 | The wreck of the Invincible, with the destroyer Badger picking up the few survivors |

| 19 | German battlecruisers in the North Sea |

| 20 | British dreadnoughts: in foreground H.M.S. Agincourt, armed with fourteen 12-inch guns; behind her H.M.S. Erin, armed with ten 13.5-inch guns |

| 21 | The finest fleet the world has seen: British battle squadrons in the North Sea |

| 22 | A salvo from the main armament of a German dreadnought |

| 23 | Scheer’s battle fleet at sea |

| 24 | Jellicoe’s flagship, H.M.S. Iron Duke, armed with ten 13.5-inch guns |

| 25 | The German dreadnought Kronprinz Wilhelm, armed with ten 12-inch guns |

| 26 | Nearly lost at Jutland: the German battlecruiser Seydlitz on fire |

| 27 | The badly damaged Seydlitz in dock at Wilhelmshaven after the action |

| 28 | Beatty’s flagship, the battlecruiser Lion, on the day after Jutland, showing her damaged ‘Q’ turret (amidships) |

| 29 | After Jutland: the damaged British light cruiser Chester |

The Author and Publishers wish to thank the following for permission to reproduce the illustrations:

Captain Garnons-Williams for fig. 28

Fine Arts Publishing Company for fig. 16

Imperial War Museum for figs. 1, 2, 6–15, 17, 18, 20–23, 26, 27 and 29 Suddeutscher Verlag, Munich for figs. 4 and 24

Verlag Ullstein, Berlin for figs. 3, 5, 19 and 25

DIAGRAMS

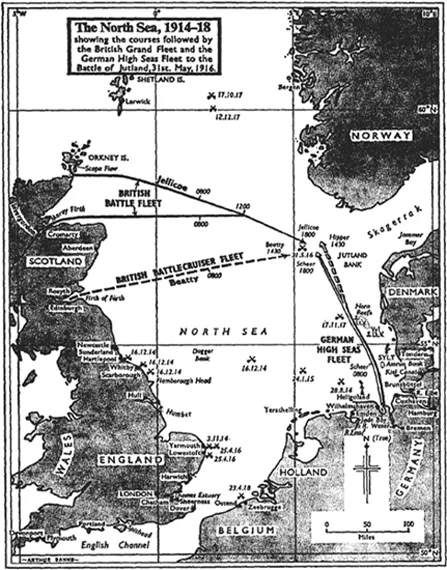

The North Sea, 1914–18

The battlecruiser action, from 1415 to 1800

The first dash between the battle fleets, from 1815 to 1845

The second clash between the battle fleets

The tracks of the two fleets during the night, 31st May–1st June

I

Genesis

‘Our future lies on the water; the trident must be in our hands’Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1892‘The only thing in the world that England has to fear is Germany.’Admiral Sir John Fisher in 1907

OF ALL the reasons advanced for the First World War one is not disputed, Germany’s decision to challenge the sea power upon which Britain counted for security from invasion and to protect her Empire and her trade. In the 50 years following Trafalgar, which climaxed the Royal Navy’s three-century struggle for maritime supremacy, the wooden-hulled ship-of-the-line remained the principal type of war vessel. In the fleets which Dundas took to the Crimea and Napier to the Baltic in 1854 there was only one significant difference from that with which Nelson and Collingwood triumphed over Villeneuve: some of their line-of-battle ships were fitted with steam as an auxiliary to sail; otherwise they were little more than larger and more heavily armed versions of the Henry Grace à Dieu of 1514. But those few steam-driven vessels heralded a revolution in warship design; in the next 45 years sail joined oars in the limbo of obsolete methods of propulsion; by the end of the nineteenth century the whole of the Royal Navy was driven by steam. This transformation was accompanied by two other innovations. ‘Wooden walls’ had sufficed to withstand the cast-iron balls of Nelson’s smooth-bored cannon; explosive-filled shell from rifled guns compelled the fitting of armour to steel hulls. And the progress of gun manufacture allowed such an increase in size that the few which could be carried had to be mounted in revolving turrets, which meant the end of the three-decker with its multi-gunned broad-sides. In 1805 the largest of the ‘far-distant, storm-beaten ships upon which the Grand Army never looked’ (Mahan) carried 120 guns, none bigger than a 32-pounder (carronades excepted), on a displacement of about 4,200 tons. By 1900, battleships displaced 13,000 tons, mounted four 12-inch plus twelve 6-inch guns and could steam at 18 knots.

Notwithstanding these developments Britain maintained her supremacy. Gladstone might try to reduce the Naval Estimates but public apprehension at the large fleet maintained by France whose ports were only a few hours steaming away, and by Russia who had designs on India and the Far East, was too strong. Successive scares, particularly that of 1885, compelled increases in the strength and readiness of the British Fleet. A navy capable of dealing with the fleets of any likely combination of Powers—Casdereagh’s Two Power standard—was the only yardstick acceptable to a public which looked to its moat: in 1900 the Royal Navy counted more than 40 battleships against France’s 26 and Russia’s 12. Only Italy and the United States had as many as ten; Japan’s six were more important because they required a comparable British force in the Far East. The remaining navies of the world were of no consequence, but percipient naval critics were already foretelling the meteoric growth of Germany’s six battleships into a fleet second only to Britain’s within so short a time as the next decade.

Behind this spectacular development was the unification of Germany (1867) and her rapid growth into a world Power. Napoleon III found a pretext for a tragic attempt to strangle Bismarck’s brainchild four years after it was born. Six weeks of war ended the Second Empire; in as many months Paris capitulated, and France was compelled to cede Alsace and Lorraine and to allow King Wilhelm of Prussia to be crowned German Emperor at Versailles in 1871. The Iron Chancellor’s ambitions were satisfied; in alliance with Austria and Italy, he aimed to preserve peace by isolating France, so that she was ‘without friends and without allies’, and by conciliating Russia. Germany’s strength rested on her victorious army; with only five ironclads to Britain’s 50 she could never aspire to command the sea. Nor was this necessary when the growth of German industry and commerce impelled Bismarck to found a modest colonial empire; by tactful diplomacy he avoided conflict with British interests.

Unfortunately Wilhelm I was succeeded in 1888 by a brash 29-year-old grandson whose actions were both reckless and impulsive, and whose considerable abilities were bedevilled by too arrogant a belief in his autocratic role. He could not stand aside whilst other European Powers grabbed Africa for themselves; he must have ‘a place in the sun’. His first obstacle to an aggressive foreign policy, the ageing Bismarck’s unchallenged authority, was soon removed: with scant courtesy, the wise old pilot was dropped in 1890. And Wilhelm was in no way perturbed when this drove France to negotiate with Russia, whereby in 1894 the Triple Alliance was opposed by a Dual Alliance which gave Germany a formidable enemy on each flank. The British Empire was an obstacle of a different order. The German Army could exert little influence on a people whose island heart was so well protected by a powerful fleet; nor was it of much value as an instrument of policy overseas so long as that fleet remained supreme. But the Reichstag was as reactionary as the federal Diet had been; it obstinately refused to vote funds for more than a small coast-defence force.

The Kaiser had, however, already found the man to realize his dream, Alfred von Tirpitz. Exceptionally able and energetic, he was a specialist in the two new weapons which the second half of the nine-teenth century added to naval armouries, the torpedo and the mine, before he became a rear-admiral and held the post of Chief of Staff to the German Navy’s High Command. Under his guidance realistic tactical exercises replaced formal manoeuvres, every encouragement being given to subordinate commanders to act on their own initiative whenever they judged that they could further their commander-in-chief’s intentions better in this way than by rigid compliance with his orders. Remembering how his own ship had been confined to Schillig Roads by the close blockade maintained by a much superior enemy fleet during the Franco-Prussian War, Tirpitz so fervently believed that Germany must build a High Seas Fleet if she was to maintain her growing power, that in 1897 the Kaiser appointed him Secretary of the Navy at the age of 48. And within a year he persuaded the Reichstag to authorize the construction of a fleet of 17 battleships to be completed in five years.

Despite Germany’s nascent hostility, revealed by the Kruger telegram of 1896 and her curt rejection of conciliatory overtures in 1898 and 1899, Britain did not believe this Navy Law to be a serious threat. Such complacency was short-lived; whilst the Kaiser openly encouraged the Boers, Tirpitz used the seizure of German merchant vessels off the African coast to inflame the Reichstag into authorizing a fleet, headed by 34 battleships (later increased to 41 plus 20 heavy cruisers) which were to be completed by 1917. The preamble to his new Navy Law made their purpose plain: ‘Germany must have a battle fleet so strong that, even for the strongest sea power, war against it would invite such dangers as to imperil its position in the world.’ This challenge could not be ignored: Lord Salisbury’s Cabinet responded by abandoning the policy of ‘splendid isolation’ conceived by Canning nearly a hundred years before, and firmly established by Palmerston with the impetus of Cobden and Bright after the Crimean War. To curtail Russia’s ambitions in the East an alliance was forged with Japan in 1902–4. Salisbury’s successor took a more momentous step: to avert the recurring danger of serious differences with France, Balfour made overtures to Paris. The resulting Entente Cordiale, where-by the Dual Alliance became a Triple Entente, was cemented at Algeciras in 1906, when an International Conference met to resolve the crisis provoked by the Kaiser’s lack of tact: in visiting Tangier when France was involved in a dispute with Morocco.

Whilst the Northcliffe Press, from The Times down to The Boy’s Friend, and men like Erskine Childers in The Riddle of the Sands, alerted the British public to the German menace, the Government began to prepare for a future clash. Balfour’s inspired creation of a Committee of Imperial Defence and the provision of a General Staff at the War Office were two much needed measures. Another was a decision to construct a naval base at Rosyth because Portsmouth and Devonport were too far away to support a fleet whose battleground would be the North Sea. But the naval consequences of the Entente were more imp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents