- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

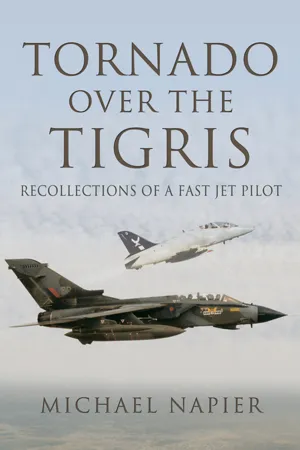

A Royal Air Force pilot recounts his service flying Tornados over Cold War-era Germany and post-Gulf War Iraq in this thrilling military memoir.

After achieving a boyhood ambition to qualify as an RAF pilot, Michael Napier was posted to RAF Bruggen in Germany where he spent five years flying Tornado GR1s at the height of the Cold War. Always exhilarating and often dangerous, Michael Napier's Tornado flying ranged from 'routine' low-flying in continental Europe and the UK to air combat maneuvering in Sardinia and the ultra-realistic Red Flag exercises in the United States.

From a struggling first-tourist to a respected four-ship leader, Napier became an instructor at the Tactical Weapons Unit at RAF Chivenor. He later returned to flying the Tornado at Bruggen as a Flight Commander shortly after the Gulf War, flying a number of operational sorties over Iraq, which included leading air-strikes against Iraqi air defense installations as part of major Coalition operations. With candor and vivid detail, Napier offers an insider's look at one of the RAF's legendary, now retired, Torando aircraft.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tornado Over the Tigris by Michael Napier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

one

FLEDGELING DAYS

You don’t forget your first trip in a fast jet. The moment when we punched through the cloud is indelibly etched on my mind, the feeling of sheer speed as the brilliant white sheet of stratus fell away behind and we hurtled upwards into the blue. Then, just minutes after we had left the runway, we were levelling off at 15,000ft. Up there, time suddenly seemed to stand still: there was hardly any sense of movement and we might have been hovering serenely in the quiet sky. The instructor gave me control and I gently moved the stick. The BAe Hawk quivered, obediently, answering to the slightest pressure from my hand. This aircraft, I realized, was a true thoroughbred, a far cry from the mule-like BAC Jet Provost T5 I’d spent the last year flying. And from here, on an August day at 15,000ft over Snowdonia, I could, for the first time, truly visualize the path which might eventually lead me to a front-line cockpit. And for the first time I could let myself believe that I might actually make it to the end. For the first time, too, I could look back along the route that had taken me up to my present vantage point. It had been a narrow, tortuous track, which wound its way across chasms and under deadfalls, sometimes looping back on itself and frequently passing more inviting false turnings. But I’d made it thus far.

The track had started gently enough: small, easy steps – just like any addiction. First a few drawings, then a whole book full and by the time I was 9 years-old I was clinically obsessed with aircraft. At school, while others had filled their ‘Interest Books’ with pictures of cars, trains, cats, dogs and furry rabbits, I had filled mine entirely with aircraft.

‘Why don’t you try cats and dogs in this book,’ suggested the teacher as she handed me a new exercise book.

‘But I’m interested in aircraft, Miss,’ I protested.

‘Yes, but you’ve just filled a whole book with aircraft, so why don’t you do something different this time,’ she persisted.

‘But I’m interested in aircraft, Miss,’ I replied yielding no ground.

‘Alright then, I suppose you could start with aircraft…’ conceded an exasperated teacher, probably in the full knowledge that the second book, too, would contain nothing else. And while my classmates read voraciously through the Famous Five books, I worked my way through Guy Gibson’s Enemy Coast Ahead and Paul Richey’s Fighter Pilot.

Books, films, Airfix models and daydreams of aircrafts kept me happy for the next few years. At my next school, in the wilds of rural Shropshire I joined the Combined Cadet Force (CCF), which seemed a first step towards fulfilling my ambition and gave me the chance to fly. Dressed in uncomfortable ‘hairy Mary’ trousers, with a parachute nearly as big as me dangling under my buttocks, I was loaded into the back of an ancient De Havilland Chipmunk. In the front seat, an equally ancient pilot was poised ready to fly me around the sky for twenty minutes of ‘Air Experience.’ I could barely see out of the back of that rattling old kite, which bore itself with none of the grace and elegance that I’d imagined of flight. In fact, the twenty minutes seemed more like a test of endurance: the combined effects of the sun’s heat magnified through the canopy, the discomfort of the battledress trousers, and the nauseating odour of oil and rubber, all competed to try to persuade me to empty the contents of my stomach into the blue bag clutched tightly in my left hand!

Not long after that, I fell at the first hurdle. At the age of 16, I reported to the grandly named Officers’ and Aircrew Selection Centre at RAF Biggin Hill, naively confident that I was about to be awarded an RAF sixth form scholarship. The next day, after taking the flying aptitude tests, my name was called out and I was instructed to report to the second door on the left. This was not good news – the doors on the left meant failure.

‘I’m afraid that I have to tell you that you have failed the aptitude tests for pilot,’ a grave-faced Wing Commander informed me, adding that I was now free to leave.

‘But I’d like to carry on with the rest of the tests, sir,’ I pleaded, explaining that I needed to know what else I had to sort out before I re-applied. He was dubious at first but I argued my point. Intrigued perhaps by my single-mindedness, he arranged for me to complete the rest of the tests. Two days later I sat opposite the wing commander once more.

‘The board has been favourably impressed,’ he told me and went on to explain what I must do before I ever came back. I must apply for a gliding course, I must spend time looking at technical drawings to learn how machines work; I must apply for a flying scholarship.

A few months later I learnt that I had been selected for a two-week gliding course over the school summer holidays. The excitement was almost unbearable as I imagined myself soaring and wheeling amongst the thermals in some sleek sailplane. The reality was rather more hard-edged, of course: the wood and canvas Kirby Cadet gliders used on the course would have looked at home on a First World War airfield and our flying was to be limited to the confines of the circuit. However, the antiquated gliders flew well enough, and their rugged construction saved me more than once from serious damage with my attempts at landing! We were kept busy and I spent the most of the time running around the airfield to retrieve gliders as they landed – the payback for the all-too-brief lessons with my long-suffering instructor. I soon realized that while I was by no means a natural pilot, I could actually do it and I was reassured to discover that I did have some aptitude for my chosen career after all. After two sun-drenched weeks, in that magnificent summer of 1976, I was sent off solo.

‘Fighter Pilot’: me at the controls of a Robin, Sywell, 1977.

A year later, I discovered that the Wing Commander at Biggin Hill had been as good as his word. I had applied for a Flying Scholarship, but had heard nothing further and assumed that I’d been rejected. Then, just before the end of the summer term, a brown OHMS envelope arrived containing an instruction to report to Sywell aerodrome near Northampton. There I would learn to fly a real aircraft. When I got to Sywell, I was delighted to find that these beasts were from an altogether different generation than the venerable gliders of the previous summer. The modern French-built Robin looked to me like a spaceship and its cockpit contained such a bewildering array of instruments that I thought I would never be able to master it. I soon discovered that the whole business of flying a real aircraft was altogether far more complex than a glider. Once again my progress was that of a plodding average student rather than a high-flying natural, but soon enough I was set loose on my own in the skies over Northamptonshire. There is a sense of complete freedom and absolute power that comes from being at the controls of an aircraft in flight: even from just 3,000ft the view is quite unlike anything that a mere earthbound mortal can see. For a 17-year-old boy whose single-minded ambition was to become a pilot, the joyous feeling of achievement was unbelievably thrilling. One glorious day I took a break from practising the manoeuvres I’d been sent up to learn. Instead I spent an hour wandering this way and that, simply enjoying the wonderful experience of flight. It was a typical July day: a flock of small cumulus clouds floated lazily at 4,000ft and the summer haze blurred the distance below the horizon. I pottered about over the Pitsford reservoir and the long-disused airfield at Harrington, bumped by the occasional thermal. Northampton sprawled in the sunshine before me, joined in their turn by Wellingborough and Kettering. Round to the north and west, the gently undulating countryside, mottled with the shadows of the clouds, completed the circle. Four weeks after I started at Sywell, I was the proud owner of a Private Pilot’s Licence (PPL).

My second visit to RAF Biggin Hill was rather more successful than the first and I joined the RAF as a university cadet in September 1978. I had fondly thought that I would pass most of my university days in the cockpit, perhaps popping into college for the occasional lecture, but such delusions were soon dashed. As a university cadet, I was told, my priority was to pass my exams – and therefore I couldn’t fly each year until I had done so. This shattering news coincided with my discovery that my chosen subject, aeronautical engineering, was about the driest imaginable, so all in all it was a disappointing start to my RAF career! Happily, at the end of the year my enthusiasm was recharged with the annual flying camp, where I learnt to fly all over again. The RAF dressed us in flying suits and helmets, and issued us with thick checklists that were to be committed to memory. It seemed as if we were flying jet fighters rather than little training aircraft and of course we were more than happy to dress up like real pilots! In any case, the Scottish Aviation Bulldog trainer, twice as powerful as the Robin I’d flown at Sywell, seemed to me such a ‘hot ship’ that it might as well have been a jet fighter.

If the three years with the University Air Squadron (UAS) were a gentle and light-hearted introduction to RAF life and a rather pleasant taster of military flying, my next stop at Initial Officer Training at the RAF College, Cranwell was neither pleasant nor lighthearted. The six months that I spent on that course still seem to me to have been an utterly pointless waste of my time, which served only to turn me from a naively enthusiastic cadet into a deeply cynical, albeit extremely fit, young officer. Even the benefit of thirty years of hindsight does not enlighten me any further as to what the course was trying to achieve. The only disappointment for me on graduation from the course was the discovery that I would remain in the restrictive and suffocating atmosphere of RAF Cranwell for my basic flying training.

Our course convened a week or so later at the School of Aviation Medicine, North Luffenham. We were a mixed bunch, mainly graduates but with a smattering of slightly younger members including Digger and Bill from New Zealand and Tim the Navy who joined us from the Senior Service. From the start we got on well together and in little time, as the course progressed, adversity bonded us tightly together. Perhaps the indication that we pulled together well was that of the fifteen who started the course, only one failed to finish. The going rate for most courses at that time was a 30 or 40 percent failure rate. I still count many on that course amongst my closest friends. Where sympathy was in short supply from the RAF system, we provided it to one-another. Those who were doing well, helped and cajoled those that weren’t, and the favours were repaid when the tables turned.

In the week at North Luffenham, we were taught about the physiological effects of flight – the effects that g-forces, lack of oxygen and spatial disorientation would have on our bodies. There were some very convincing practical demonstrations, including an ejection seat which fired up a test rig. It was a rather uncanny experience to strap into the seat, pull the firing handle and then find oneself, just a few milliseconds later, looking down on the tops of everyone else’s heads 20ft below with no recollection of how one got there! The course culminated in an exercise in the decompression chamber to demonstrate the effects of a catastrophic loss of pressurisation at high-level and to show us the symptoms of hypoxia. Pointing out that after a decompression there would be a much greater air pressure inside the body than outside it, our friendly doctor advised us lay off the beer and avoid spicy food the night before. Of course we were far too wise to heed the advice of a mere doctor. It was a decision that we came to regret when, one by one, we had to take off our oxygen masks and breath in the heady aroma after fifteen sweaty bottoms had discharged the gaseous remnants of chicken vindaloo and Ruddles beer into the confined space of the chamber. The next week, a somewhat wiser and more cohesive group, we headed back to RAF Cranwell and the start of ground school.

Ground school at Cranwell was chiefly memorable for the allocation of nicknames. One morning we arrived at our classroom to find that one of the senior courses had defaced all our name cards. Many of the graffiti names stuck. I thought it would be best if I did not object too strongly to being called ‘Mike the Knife,’ as I reckoned if I said nothing it would eventually go away. In this I was correct, although the ‘eventually’ was about five years longer than I had hoped! Poor old Jules, earnest and scrupulously honest as ever, was foolish enough to let everyone know that he did not like his new name at all, with the result that he became known as ‘Fatty’ to a generation of RAF aircrew.

The good news when we got onto the flying course was that Cranwell was exclusively equipped with the Jet Provost T5 (JP5), the ultimate mark of this training aircraft. Those lucky enough to complete their training in the comparatively civilized environment of the Vale of York flying training schools had to suffer a gutless earlier version, whose throttle lever varied the noise, but not the thrust, coming from the engine. In comparison our JP5s were powerful and fast, but even so I found the machine to be a complete pig, and I cannot claim to have enjoyed the year that I spent flying it.

Despite the fact that we were now ‘proper officers’ our status as student pilots meant that everyone else on the station regarded us as the lowest of the low. One particularly irksome manifestation of this snobbery was when the President of the Mess Committee (PMC) decided that the car parking spaces nearest to the Officers’ Mess should be reserved for instructional staff. Small numbered metal signs were put in front of each space and each instructor was allocated his own numbered slot. This was an injustice too far for JC and me, so we decided to do something about it. That night, in the very early hours, we crept out and removed every single sign. We put them into the boot of JC’s car and headed out into darkest rural Lincolnshire. Here we found a suitably deep drainage ditch and flung the signs into it. Our little victory lasted only a few weeks, though: the PMC ordered the numbers to be painted on the tarmac!

96 Hawk Course, RAF Valley, 1983: Standing l-r: Jules, Tim, Digger, Neil, Me, and Spot; kneeling l-r: ET, Trevor, and AJ.

JC’s car, a magnificent Ford Capri, was our vehicle of choice to get to and from the local pubs of an evening. It took us to some wonderful places but got us into trouble, too. When we came back from the pub one winter evening, JC thought that it would be great fun to perform hand-brake turns in the snow. We drove onto the parade ground at the front of the college and spent a happy ten minutes skidding sideways round it, confident that no one could see us in the darkness. The only obstacles were some small flag posts that someone had carelessly left out on the parade ground. The following morning, standing stiffly to attention in the chief instructor’s office, we discovered that the flags were the markers for that morning’s initial officer training graduation parade and that the commandant was none too pleased at the random tyre tracks that had appeared across his parade ground overnight! Unfortunately the same tyre tracks had led the RAF police straight to the culprit.

The flying syllabus at Cranwell was virtually identical to that at the UAS, except that the Jet Provost went higher and faster than the Bulldog, so all the speeds, heights and distances were much greater. Even so, it didn’t seem any easier and I found the course hard work. RAF flying training is a hard school, with lots of pressure and many opportunities to fail to make the grade. The course required a steep learning curve with frequent ‘check rides’ to make sure that the student was making sufficiently good progress. It was like a hurdle race with every hurdle to be cleared if you are to pass, and little scope for extra time for those who didn’t come up to scratch. For all of us the fear of failing was very real and coloured our entire time at Cranwell: it seemed that a last ‘chop ride’ was lurking round every corner. My favourite days were the foggy ones where there was no chance to fly and therefore no chance of getting chopped. It was a bit like being on ‘Death Row’, savouring each day as possibly one’s last as a pilot. Somehow though, I managed to plough a steadily average furrow through the course and was selected for fast jets, another step towards the goal of becoming a fighter pilot. The only close call I had was failing my final handling test for, amongst other things, not having clean boots! Mindless trivia was never far from the surface at Cranwell. I was absolutely delighted to see the place in the rear view mirror of my car as, with a sense of liberation, I headed towards the island of Anglesey in North Wales and RAF Valley.

RAF Valley, the home of advanced flying training, was a breath of fresh air both literally and metaphorically. Here the bracing winds blowing off the Irish Sea were mixed with burning kerosene and infused with testosterone to give a thrilling atmosphere of exciting anticipation. We flew the Hawk, a fantastic sports car of an aircraft, which was everything the Jet Provost was not – and more. The feelings of exhilaration, wonderment and power that I’d experienced as a 17 year-old in a light aircraft were as nothing compared to the sensations of flying a real, fast jet. All the enthusiasm that Cranwell had done its best to knock out of me came back with a vengeance. Our Cranwell course had been divided for the smaller Valley course and e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Dedication

- Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

- Epiphany

- Chapter 1: Fledgling Days

- Chapter 2: The First Crusade

- Chapter 3: Stars of Gold

- Chapter 4: Heaven in Devon

- Chapter 5: Destination Dhahran

- Chapter 6: Doing It for Real

- Chapter 7: Snapshots from the Last Crusade

- Glossary