eBook - ePub

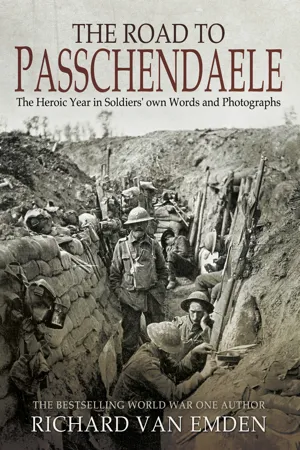

The Road to Passchendaele

The Heroic Year in Soldiers' Own Words and Photographs

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A history of World War I's Battle of Passchendaele featuring words and photographs from the British soldiers who were there.

Passchendaele is the next volume in the highly-regarded series of books from the best-selling First World War historian Richard van Emden. Once again, using the winning formula of diaries and memoirs, and above all original photographs taken on illegally-held cameras by the soldiers themselves, Richard tells the story of 1917, of life both in and out of the line culminating in perhaps the most dreaded battle of them all, the Battle of Passchendaele.

The author has an outstanding collection of over 5,000 privately-taken and overwhelmingly unpublished photographs, revealing the war as it was seen by the men involved, an existence that was sometimes exhilarating, too often terrifying, and occasionally even fun. Richard van Emden interviewed 270 veterans of the Great War, has written extensively about the soldiers' lives, and has worked on many television documentaries, always concentrating on the human aspects of war, its challenge and its cost to the millions of men involved.

Passchendaele is the next volume in the highly-regarded series of books from the best-selling First World War historian Richard van Emden. Once again, using the winning formula of diaries and memoirs, and above all original photographs taken on illegally-held cameras by the soldiers themselves, Richard tells the story of 1917, of life both in and out of the line culminating in perhaps the most dreaded battle of them all, the Battle of Passchendaele.

The author has an outstanding collection of over 5,000 privately-taken and overwhelmingly unpublished photographs, revealing the war as it was seen by the men involved, an existence that was sometimes exhilarating, too often terrifying, and occasionally even fun. Richard van Emden interviewed 270 veterans of the Great War, has written extensively about the soldiers' lives, and has worked on many television documentaries, always concentrating on the human aspects of war, its challenge and its cost to the millions of men involved.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Road to Passchendaele by Richard van Emden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Winter Wonderland

January 1917, near Combles village. The frozen wasteland of the Somme Battlefield.

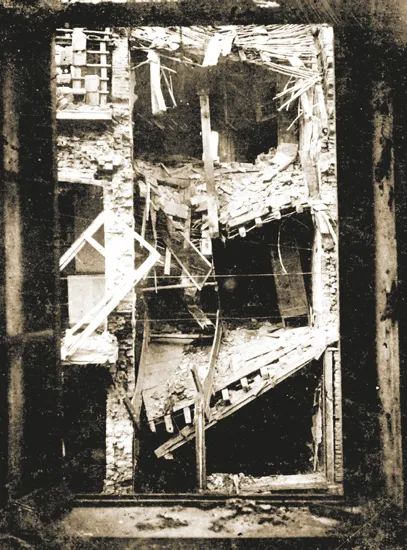

A direct hit: a house made uninhabitable by shellfire.

‘We are not ashamed of being afraid, as we often are not afraid of any definite thing, but just afraid of being afraid; when the time for action comes there is little time for fear. In warfare only cowards are the really brave men, for they have to force themselves to do things that brave men do instinctively.’

Lieutenant George Brown, 9th The Suffolk Regiment

As each year of conflict ended and a new one began, there was an opportunity for a pause, a traditional festive moment of reflection when men could look back upon the year that was and forward to what might be. The war had not been brought to a successful conclusion, clearly, but surely the New Year would bring victory? These were thoughts common to troops of every nationality, resolutely optimistic that they would prevail. British and Empire troops, feet stamping in draughty camps and freezing trenches, held a conviction as strong as anyone of victory, not necessarily straightaway, but at some point during the forthcoming calendar year. Back in January 1915 it mattered little that there was physical evidence to the contrary – the enemy’s predominance in men and munitions – rather, the manifest virtue of Britain’s cause and her conspicuous power built on Empire would provide the impetus for success. Princess Mary had included that presumption in her festive gift, her present of 1914, given to all soldiers on the Western Front. Tucked under the packets of tobacco and cigarettes – a slab of acid drop in paper for non-smokers – was a small envelope: inside, her picture and her message wishing all a happy Christmas ‘and a Victorious New Year’.

Twelve months later, many soldiers again expected success, as was made apparent in letters and diaries. There were more tangible reasons for hope by 1916. The British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, had recruited his New Army of civilians-turned-soldiers on the outbreak of war, and they were now pouring into France. These men were taking much of the strain so courageously borne by Regular and Territorial troops that had held the German Army in check. Now anyone who had been abroad twelve months or more could hardly fail to notice the exponential growth in troop numbers or the near parity between British and German arms – no more scandalous rationing of artillery shells to the Royal Field Artillery, as had happened in early 1915.‘Old sweats’, as these soldiers liked to see themselves, could compare and contrast not only the ebb and flow of the fighting but its changing nature too. The Battle of the Somme in 1916 had ushered in a profound change. The ‘Big Push’, as it was known, was fully fledged industrial warfare and of an entirely different order from anything the British Army had been involved in … ever. Artillery bombardments were frequently of stupefying length and intensity, and tanks, that ingenious product of focused war minds, had made their debut, a very visceral and visual addition to the panoply of new battlefield weapons. On the defensive, the German Army fought with tenacity, and British troops could not but grudgingly acknowledge the enemy’s stubbornness and resolve. In four and a half months, the Germans relinquished slivers of tortured ground and showed no signs of military collapse. It was now a foolhardy man who blithely predicted Allied victory in 1917, and those who spoke of the future were circumspect in what they said. Lieutenant Paul Jones took a moment for reflection on 1 January 1917 when he wrote home to his family. He had been in France eighteen months:

Hearty wishes for a happy New Year, wishes which always seem to me more serious than the greetings that pass at Christmas time. With most people Christmas is a purely festive season, but with the end of the old year comes the necessity of looking forward to a new period – perhaps to be joyful, perhaps otherwise; anyway, a period on which it is necessary to enter as far as possible with confidence. From the general point of view that is not an easy matter as things stand. I am bound to say I am getting pessimistic about the war. The chief trouble is the total lack of action that characterizes it. This grovelling in ditches is a rotten, foolish business in many ways.

Ditch grovelling had been the war’s chief characteristic since autumn 1914, when entrenching was the only sensible reaction to machine guns and artillery fire that made unprotected exposure to their combined power lethal. Since then, the ground into which men had hunkered gradually altered from fields that looked agricultural to something otherworldly, more moonscape than landscape. Only concerted action brought large numbers of men out into the open, but time and again the ‘defensive’ trumped the ‘offensive’ and no-man’s-land would resume its wasteland characteristics, observed through the infantryman’s trench periscope or, looking down, viewed from the pilot’s cockpit.

The Battle of Verdun, launched by the Germans against the French in February 1916, and the Allied Somme offensive, launched in July, were supreme tests of man’s endurance. Numerically, the Germans lost more troops on the Western Front than any other single country and resolved, out of tactical necessity, to alter the situation. The Battle of the Somme had been fought within a large and, with the benefit of hindsight, rather unwieldy bulge in the German lines. This ‘bulge’ meant more German troops were deployed to occupy the front line than would otherwise be the case had it been straighter. For the first time in the war, circumstances forced the Germans to value lives more highly than holding land, so a decision was taken to withdraw to a newly constructed, intensely defended trench system. The Germans named it the Siegfried Stellung; to the Allies it was the Hindenburg Line.

When the Germans began to pull back to this new position in March 1917, British troops wondered whether the withdrawal might adversely affect the enemy’s morale: but after all the disappointments of the last two years, many nebulously ‘hoped’ the war might end soon but fewer extrapolated further. Nevertheless, the Germans’ withdrawal from land they had fought so hard to hold was suggestive of weakness rather than strength. The current was turning against the Germans and should have given the Allies cause for quiet optimism. On the Western Front, the balance of physical power was slowly, irresistibly and perceptibly moving in favour of the Allies, while elsewhere, diplomatically, the Germans had been the first to put out tentative feelers for a negotiated peace. These first moves came to nothing, but it suggested that the enemy was no longer confident of ultimate victory.

1917 would be a hateful year. The German launch of unrestricted submarine warfare was their attempt to starve Britain into submission, just as the Allies were attempting the same to the Germans by their use of a maritime blockade. On the Western Front, the year would be characterized by perhaps the bitterest fighting of the war, an unprecedented slugfest. The niceties of war were consigned to the past: any idea of a Christmas Truce, as had so famously occurred in 1914 and to a lesser extent in 1915, belonged to another world. War was a serious business and best business practice required results without sympathy, unnecessary inefficiency or delay. The Germans, the Allies decided, would be harried at every possible turn.

Whereas the battles of 1916 had been fought in the main by Kitchener’s Army, war in 1917 would be prosecuted by increasing numbers of conscripted men, men who did not want to be in France a moment longer than necessary. Those who fought did so with grim determination to see the war to its conclusion, reluctantly resigned to whatever fate had in store. This attitude percolated down to French and Belgian civilians too, who had grown used to enemy shelling and displayed an astonishing level of sangfroid while clinging to their towns and villages within the war zone. But while the Germans were the greatest enemy, in the first months of 1917 soldiers and civilians alike would be challenged by another formidable adversary: the winter weather, the bitterest in living memory.

January 1917: Tank C16 abandoned between Leuze Wood and Combles on the Somme. It was knocked out by a British shell falling short, 15 September 1916.

Lieutenant Colonel Rowland Feilding, 6th The Connaught Rangers, Cooker Farm, facing Messines-Wytschaete Ridge, near Ypres

25 December 1916: Though this is Christmas Day, things have not been as quiet as they might have been, though we have not suffered. I fancy the battalion on our right has done so to some extent. In fact, as I passed along their fire trench, I saw them at work, digging some poor fellows out who had been buried by a trench mortar bomb.

This evening since dark, for a couple of hours, the Germans have been bombarding some place behind us with heavy shells. The battery from which the fire is coming is so far away that I cannot even faintly hear the report of the guns while I am in the open trench, though, from the dugout from which I now write, I can just distinguish it, transmitted through the medium of the ground. I can hear the shells at a great altitude overhead rushing through the air. …

I went round and wished the men – scarcely a Merry Christmas, but good luck in the New Year, and may they never have to spend another Christmas in the front line! This meant much repetition on my part.

I have a good many recruits just now. Some of them went into the line for the first time last night. I visited them at their posts soon after they had reached the fire trench, and asked them how they liked it. They are just boys feeling their way. They wore a rather bewildered look.

30 December: Today, the battalion being out of the trenches, we celebrated Christmas in a sort of way; that is to say, the men had turkey and plumpudding, and French beer for dinner, and a holiday from ‘fatigues’.

I hope they enjoyed it. The extras – over and above those contributed by friends at home (whose presents had been very liberal) – cost the battalion funds around £90. But when I went round and saw the dinners I must confess I was disappointed. Our surroundings do not lend themselves to this kind of entertainment; and, as to appliances – tables, plates, cutlery, etc. – well, we have none. The turkeys had to be cut into shreds and dished up in the mess tins. Beer had to be ladled out of buckets (or rather dixies) later, into the same mess tins; out of which also the plum pudding was taken, the men sitting herded about on the floors of dark huts. …

Although well within range of the daily shellfire, there is a woman with a baby living in the farm where I and my headquarter officers’ mess. There have, during the past few days, been some heavy bombardments, directed at our batteries in the immediate neighbourhood, in fact in the adjacent fields, some of which are sprinkled like pepper pots with shell holes. There is a hole through the roof of the hut in which I live, made by shrapnel, and I admit that the thought of the battalion with nothing but galvanized roofing and thick wooden walls between it and the enemy, is at times depressing. The place is indeed most unsuited for a ‘Rest’ Camp, which it is supposed to be, and still less for a nursery.

Still, the woman with the baby clings to her home. I wonder at these women with their babies. They must be possessed of boundless faith. There seems to be a sort of fatalism, and, as a matter of fact, they seldom get injured.

31 December (midnight): It is midnight. As I write, all the heavies we possess are loosing off their New Year’s ‘Joy’ to the Germans, making my hut vibrate. The men in their huts are cheering and singing Old Lang Syne.

The rumpus started at five minutes to twelve. Now, as it strikes the hour, all has stopped, including the singing as suddenly as it began. The guns awakened the men, who clearly approved. The enemy has not replied with a single shot in this direction.

1 January 1917: We heard Mass again this – New Year’s – morning; our third Sunday in three days! The first our Christmas Day; the second yesterday, the real Sunday when Monseigneur Ryan, from Tipperary, preached; the third, today.

In spite of the heavy calls for working parties for the front line each day and night, the men off duty toll up always, and march behind the drums to wherever the service may be – in small parties, of course, owing to the proximity of the firing line.

Pray for them as hard as you possibly can.

9 January [facing Messines-Wytschaete Ridge]: After a peaceful day yesterday the enemy is at it again very vicious (I suppose auxiliary to his peace negotiations), and is plastering the place with thousands of trench mortar bombs and shells; doing precious little harm; – like a naughty child breaking its toys out of spite, but necessitating a good deal of repair work on our part. We give him back a good deal more than we get, and it must all be very expensive. The whole place is a sea of mud and misery, but I must not grumble at the mud. It saves many thousands of lives by localizing the shell bursts, and by muffling those very nasty German trench mortar bombs.

14 January: We came out of the trenches last night. I could not describe them if I tried, but they are more wretched looking than any I have seen since I came to the war.

The most imaginative mind could not conceive an adequate picture of the frail and battered wall of shredded sandbags without actually seeing it, nor the heroic manner in which the men who hold it face its dangers and discomforts; – the mud and the slush and the snow; often knee-deep, and deeper still, in water. The foulest of weather; four days and nights (sometimes five) without moving from one spot; pounded incessantly with what the soldiers call ‘rum-jars’ – great canisters of high explosive, fired from wooden mortars, making monstrous explosions; and often in addition going through an hour or two during the day or night – sometimes two or three times during the twenty-four hours – of intense bombardment by these things as well as by every other sort of atrocity the enemy knows how to use. …

From the front line, after eight days, the battalion goes into Brigade Reserve. Even from there the men go up to the front line most nights on working parties, and are pounded again. Then eight days in the front line once more.

CQMS William Andrews, 1/4th The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)

I suppose men now going about in short frocks will thrill thirty years hence as they read of our adventures – of charging over the dead-littered no-man’s-land against the battered German lines, or running hell for leather through a barrage of shells, or bringing in wounded under fire. These readers will envy us our romances of danger. They will hardly realize how dull and dirty war really is, what a fight we have against lousiness and trench inertia. How thoroughly ‘fed-up with the whole issue’ every soldier is, save, perhaps, a few young gentlemen who, previously aimless, now find responsibility, the exercise of command and caste exclusiveness, much to their liking. … For myself I dislike this life, not so much because it is dull and unprofitable. The censor has pretty well stifled the journalistic me – it is the people at home who are writing most of the war stuff. But we must go on and not lose heart. We had to fight this war, and we must win it. We must not be disloyal to our dead.

Second Lieutenant Harold Parry, 17th The King’s Royal Rifle Corps

14 February: After a break of two days it has started freezing here again, and we are once more back in the somewhat sub-arctic state of affairs to which we had become accustomed. It just thawed enough to make everything muddy on the top, and whatever progress one made was rendered precarious by the fact that one never quite knew what either foot was doing at a specified moment. One foot might be planted with Horatian firmness on an obvious and non-treacherous spot, the other would glide down into a welter of mud and water and snow ice, such as one becomes especially and reluctantly conversant with out...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Winter Wonderland

- Chapter 2 Opportunity Knocking

- Chapter 3 Opportunity Lost

- Chapter 4 Summer Success

- Chapter 5 Fresh Air and Exercise

- Chapter 6 Armageddon Calling

- Chapter 7 Blood and Mud

- Chapter 8 Bite and Hold

- Endpiece

- Acknowledgements

- Sources and Permissions

- A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR