- 736 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This, the fourth volume in Andrew Field's highly praised study of the Waterloo campaign from the French perspective, depicts in vivid detail the often neglected final phase the rout and retreat of Napoleon's army. The text is based exclusively on French eyewitness accounts which give an inside view of the immediate aftermath of the battle and carry the story through to the army's disbandment in late 1815. Many French officers and soldiers wrote more about the retreat than they did about the catastrophe of Waterloo itself. Their recollections give a fascinating insight to the psyche of the French soldier. They also provide a firsthand record of their experiences and the range of their reactions, from those who deserted the colors and made their way home, to those who continued to serve faithfully when all was lost. Napoleons own flight from Waterloo is an essential part of the narrative, but the main emphasis is on the fate of the beaten French army as it was experienced by eyewitnesses who lived through the last days of the campaign.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Waterloo: The Campaign of 1815, Volume 1 by John Hussey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Europe’s Experience of Napoleon

1797–1814

I

THE HUNDRED DAYS AND THE CAMPAIGN OF 1815 comprise a great drama in themselves, but are also the final episode in the extraordinary Napoleonic adventure. Thus they do not stand totally apart from the preceding events; and nor did the participants of the time think they did. If we are to understand the minds and actions of the sovereigns and politicians – and the generals who fought their battles – we need to remember that although ‘the return from Elba’ was indeed the act that brought on fresh troubles, the key to what followed lies in their long experience of Napoleon. There were, of course, other factors as well. The ‘return’ would have been impossible without the discontents in France that arose from the Bourbon Restoration in 1814. But in addition, international disputes in the winter of 1814/15 almost wrecked the victorious alliance of spring and summer 1814, and brought its members to the point of war - this, too, encouraged Napoleon in his dreams. Just as he, the inveterate calculator of odds, gambled upon negotiating some form of settlement with individual European powers once he was again in possession of France, so the powers – wise from their experience of seventeen years’ dealings with Bonaparte as general, consul and emperor, and the experience of Napoleonic domination – refused all compromise and sought his total overthrow.

The statesmen of Europe’s response to the ‘return’, thus stemmed from Europe’s own knowledge of Napoleon’s aims and Napoleon’s methods. To wage war, to extend his rule ever further afield, to dream of universal empire, to use diplomacy to divide his enemies and chicanery to confuse his allies (and the terms enemy and ally could become interchangeable in any situation), to mislead by propaganda, to impose an authoritarian system of government promoting across Europe policies mainly to benefit France, these were the hallmarks of his rule. But it went further, for it was not so much a pro-French rule but a personal rule, whereby everything had to depend upon Napoleon’s own predilections and contribute to his own position. And since he relished his genius for war1 it meant the imposition on France and tributary Europe of the hated conscription, the levying of heavy taxes, and the burden of a mercantilist Continental System. How had this come about? How was it to end? The answers lie in the personality of that child of the Revolution, Napoleon himself, and that necessitates a retrospective digression that yet is not wholly a digression.

II

The French Revolution in its domestic aspect had in the space of three or four years destroyed much of the old administration of the country, secularised the Church and then abolished Christianity (to the horror of many French people and certainly of the Pope), changed the system of land tenure, altered and upset the finances of the country, and had proposed (with popular endorsement) three new constitutions of 1791, 1793 and 1795 (and implemented the first and third – though not the embarrassingly liberal constitution of 1793). It had seen government more than ever centralised in Paris, and this Paris at the mercy of extremists vying with each other in a revolutionary fervour that culminated in the Great Terror. It had seen most of the old ties of society dissolved, the monarchy and aristocracy abolished, the King and Queen and countless others executed, down to ordinary citizens against whom private grudges could be turned into death sentences in people’s courts. It had resulted in civil war in the west and south, and troubles elsewhere. Such were the singular and bloody outcomes of the great ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of Citizen’ of October 1789 and the call for ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity’. After a decade of upheaval and destruction, France was a country in need of calm and order, of stable and firm administration, and good government. That is what Bonaparte boldly promised in 1799.

Europe’s attitude to the French Revolution was at first benign, in that most statesmen expected France to be so engaged in internal reform that it would play no active part in the affairs of the world. This meant that it would no longer concern itself with the balance of power, leaving its operation to other states. For the balance, the ‘just equilibrium’, had been fundamental to Europe for centuries, and it operated as a constant adjustment between states to restrain the ambitious from interfering with the independence of the rest. ‘Political relations,’ wrote Clausewitz, ‘with their affinities and antipathies, had become so sensitive a nexus that no cannon could be fired in Europe without every government feeling its interest affected.’ And he noted that this sensitivity created counter-balancing interests against a war-bent monarch, so that ‘his conquests rarely amounted to very much’.2 Thus great coalitions had formed against the over-mighty – as in Louis XIV’s time – but then evolved into different combinations once their work was done. But there was a second principle, partition, that could be invoked in defence of the balance (as over the future of the Spanish dominions in the 1690s) or when a state was so weak, isolated and friendless, that it could be taken apart without risk of a general war (as in the case of Poland, 1772–95).

What was not expected in 1789 and 1790 was the revolutionary, militant, and universal doctrine that emerged from Paris, declaring France the friend and champion of all oppressed peoples regardless of frontiers and old treaties. The Revolution demanded ‘the natural frontiers’ of the Rhine, the Alps, the Pyrenees, and soon demanded annexations even further afield. (It is one of the quirks in that revolutionary extremist Robespierre’s character that he was against war with Europe.) Despite occasional successes, the allies against France, working on the old principles and watching against the ambitions of their partners in areas far from western Europe, failed to check the revolutionary impetus. France, though initially almost broken by defeats and poor organisation, made desperate efforts to rebuild its army and instituted the levée en masse that produced some 800,000 soldiers (although this had fallen to some 365,000 by late 1797). After France’s leaders promoted a new generation of ruthless commissioners and threatened its commanders with victory or death, able generals emerged, like Hoche, Bernadotte, Moreau, Joubert – and Bonaparte. That the Revolutionary Wars gave France so many victories and produced so many annexations thus was due to factors positive and negative: to propaganda; to deployment of its abundant manpower (only Austria and Russia had similar numbers, and these were heterogeneous and poorly organised); to the divisions and backslidings among German states that hampered any Allied plans; to the diversion caused by the partitions of Poland between Austria, Prussia and Russia; and to the distracting hopes of Austria and Russia for a dismemberment of Turkey. The cautious exponents of the traditional balance of power and of the Realpolitik of partition between friends were challenged by a messianic universalist creed and a mass army.

Under this impulsion, France’s ‘natural frontiers’, including parts of Rhenish Germany and all Belgium were soon attained.3 Holland was overrun. France’s new government of five Directors had little part in all this; it was the initiative of their generals that brought success. The legal incorporation of Austria’s Belgian provinces into France was confirmed internationally by Bonaparte’s Treaty of Campo-Formio in 1797 with Austria, which gave international recognition to the natural frontiers, left Piedmont under military occupation, created satellite republics in north-central Italy, and partitioned the venerable Venetian Republic with Austria. It was also a treaty that Bonaparte negotiated without consideration for the French government’s views or for their authority, being the outcome of his astonishing Italian campaigns of 1796 and 1797 that took him to within a hundred miles of Vienna. In 1798 Switzerland was overrun and the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples became satellite republics. Then came the unsuccessful campaign beyond the Mediterranean in Egypt and Palestine.

III

Seventeen-ninety-seven thus marks a fundamental change in French policy, with France now seeking frontiers beyond even the natural ones; drawing upon its allies and the cluster of satellites round its frontiers for its war finance and manpower: as Napoleon instructed Marshal Soult in 1810, ‘war should feed war’. Whatever may be said for the first phase of the war, from 1797 the ‘idea’ of the Revolution was subordinated in the mind of France’s leading general to mere power politics.4

The five-man Directorate was divided within itself. Having failed to isolate and subdue this semi-independent Bonaparte, who acted like a co-equal, some Directors (with the aid of Police Minister Fouché) decided to use him for a coup against the others. The outcome, famously, was 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 November 1799). Given what was to follow in the next fifteen years, there is an irony in Bonaparte’s public declaration on that morning that he had come to ‘save … and uphold … a republic founded on liberty, on equality, on the sacred principles of national representation’.5 The next day troops suppressed the legislature at bayonet point. Throwing over his duped sponsors, Bonaparte became First Consul with vast powers.

What followed during the Consular years (1799–1804) was a great and astonishingly complete set of organisational reforms that are a tribute to Napoleon Bonaparte’s amazing genius and constitute his most enduring claim to fame, reforms that in any biography would fill many chapters; indeed, studies of Consular and Imperial social and administrative developments are now as frequent as military ones.6 But Napoleon’s purpose was always clear: to enforce uniformity, and do so for the purpose of raising men and money for ever more extended war. The great French historian Albert Vandal summed up 18 Brumaire and Bonaparte’s organisational reforms of Year VIII (essentially the prefectorial system) as ‘the single will from above penetrating and directing every level and all parts of society to impose uniformity’; its defect (Vandal said) was to hand all power, governmental and administrative, to the agents of the central authority: the ‘citizens’ of the great Declaration of Rights found themselves without any share in the management of their own interests through directly elected representatives, so that in public and collective life they were left impotent:7 those who hoped Bonaparte had come to save the republic found themselves under a new autocracy. The Napoleonic police state watched everyone, controlled everything. Censorship suppressed independent thought: Mozart’s Don Giovanni was only allowed to play when Napoleon was satisfied that the audience would learn nothing dangerous from it. The press suffered repeatedly: in 1800 seventy-three newspapers were suppressed, and in 1803 - ‘in order to secure the liberty [sic] of the Press’ - a reviewing committee was established to check whether proposed news items merited censorship. Only four newspapers were allowed in Paris, and all had to follow the Moniteur’s line, which was written in the Ministère des affaires étrangères. And there was too casual an attitude to justice and fair process, and a savagery in punishing all opposition – such as the deportation of inconvenient Jacobins to Cayenne and the Indian Ocean, the death of Frotté, the murder of the Duc d’Enghien – that stains the regime.8

This defect, already grave during the Consulate, worsened under the Empire, and it posed a terrible risk. The Constitution of Year VIII (1799) had aimed at a separation of powers between institutions (named from Roman precedent): an executive elected Consulate to whom ministers reported, a Tribunate of the people to propose and debate laws, a Legislature limited to voting silently and in private on the proposed laws but not to debate them, and a Senate to guard the laws. Bonaparte swiftly brought these bodies to heel by a continual series of changes that they seemed powerless to withstand. By 1807 the Tribunate had been gagged and virtually disappeared through his decision to place it within the silent Legislature that itself had become a mere confirmatory registrar for executive proposals. Although the Senate was empowered to amend the constitution by issuing a ‘sénatus-consulte’ (such as that emasculating the right of trial by jury), all such proposed changes had to emanate from a demand by the Consulate (later the Emperor). Richly rewarded for its docility, the Senate became notorious for its servility towards the executive. Judicial independence was weakened by requiring each judge first to serve a five-year probationary period, with final confirmation depending on a Senate committee nominated by the Emperor. Imprisonment for political matters thus became easier.9 The individual suffered; but so did the health of the state, for the risk to the state was that, should the central authority fail, the country might lack the power to manage for itself. And with Napoleon’s mania for centralisation and personal rule, exactly that was to happen in 1814.

Externally, the expansion continued. By the short-lived peace treaties of Lunéville in 1801 and Amiens in 1802, additional lands were gained for France, but the principal advantage for Napoleon was his right by treaty to involve himself in the constitutional affairs of Germany.

War against Britain was renewed in 1803 and, once Pitt had constructed a Third European Coalition in 1805, the struggle spread to the Continent, and at a terrible cost. The first step had been the French occupation of Hanover (despite its declared neutrality) prior to Napoleon handing it to Prussia in 1805. The fears of Russia and Austria in 1805 and their coalition with Britain led only to Allied disaster at Austerlitz, and the cession by Austria of three million subjects and of Venetia and the Dalmatian coast to Napoleon in his new role as King of Italy. The year 1806 saw the establishment of the French protectorate in Germany with the Confederation of the Rhine stretching from south Tyrol to well north of Cologne. Prussia’s belated declaration of war led to the disasters of Jena and Auerstädt and to the loss of all its lands west of the Elbe (including Hanover) and much of its Polish territory. Indeed, but for Tsar Alexander’s intervention, Prussia might have been totally dismembered; as it was, it survived as a submissive vassal to Napoleon’s cause until 1813.10 France meanwhile approached the Ottoman Empire with an opportunistic suggestion to carve away parts of Russia. Napoleon’s onslaughts against Russian armies at Eylau and Friedland forced Alexander to the conference at Tilsit (end of June 1807), where France and Russia settled the balance of Europe between them, and Napoleon blithely discussed a joint attack on the Ottomans and India.

That year saw a Franco-Spanish treaty for the partition of Portugal, and in consequence the movement into Spain of French armies. Following this the revered if degenerate Spanish royal dynasty were collectively inveigled to Bayonne, imprisoned and deposed in favour of vain, well-meaning Joseph Bonaparte. It was a direct challenge to legitimacy and national institutions: monarchies like Austria that were dynastic and not national had growing cause for apprehension. In 1809 Rome was annexed. Pope Pius VII retaliated by excommunicating Napoleon; the Emperor ordered Murat to seize him; and the Pope found himself imprisoned in France. Everywhere thrones and titles were given to inadequate or frivolous Bonaparte brothers and sisters. No hereditary crown was safe.

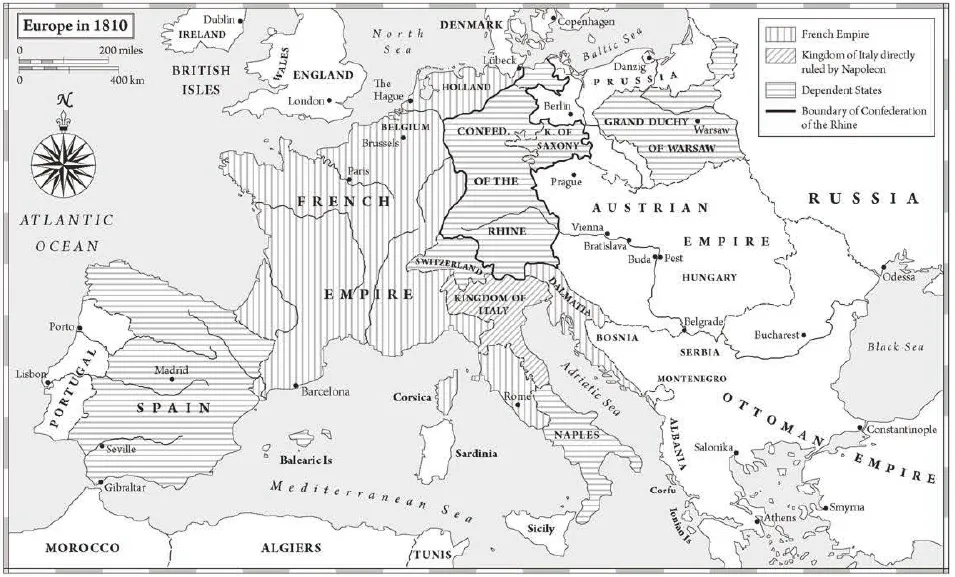

French troops were now holding Poland, which by 1809 had become the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, created from former Austrian and Prussian possessions. The Confederation of the Rhine had expanded north and eastwards. Austria’s decision to challenge Napoleon in a fresh war in 1809 merely led to the loss of its Salzburg province and more of its Balkan lands of Carniola and Croatia. By 1810 all Holland, plus north-west Germany11 as far east as the Hanseatic cities of Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck, plus the Swiss Valais, plus Catalonia, and almost half Italy, were i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Plates and Illustrations

- List of Maps and Tables

- Foreword by Hew Strachan

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Europe’s Experience of Napoleon: 1797–1814

- Chapter 2 Losing the Peace: 1824–1815

- Chapter 3 Elba: Sovereignty and Surveillance

- Chapter 4 From Usurper to Emperor: Golfe Juan to the Tuileries

- Chapter 5 Europe’s Response

- Chapter 6 Two Styles of Command: Wellington and the Prussians

- Chapter 7 Europe and the Belgian Question

- Chapter 8 Establishing a Strategy for Belgium: April 1815

- Chapter 9 A Measure of Give and Take: Provisioning the Allied Armies in 1815

- Chapter 10 Strengthening the Armies: From April 1815 Onwards

- Chapter 11 Two Crises in Early May: A Threat of Attack and the Saxon Mutiny

- Chapter 12 Ehe Aftermath of Tirlemont: Early and Mid-May

- Chapter 13 Prussian Thinking on the War Plan and Blücher’s Visit to Brussels: May–June 1815

- Chapter 14 Napoleon and his Options: Spring 1815

- Chapter 15 Allied Intelligence and Assessments of Napoleon’s Options: Twelve Days in June

- Chapter 16 All Too Quiet on the Eastern Front: Debates, Reconsiderations, Delays, March–June 1815

- Chapter 17 Preparing to Enter France: Towards Mid-June 1815

- Chapter 18 The Anniversary of Marengo and Friedland: Wednesday 14 June 1815

- Chapter 19 Napoleon in Paris and the Preparations for the Campaign: 1–14 June 1815

- Chapter 20 Thursday 15 June 1815: The Day for the French

- Chapter 21 The Prussians on 15 June

- Chapter 22 How the News Came to Brussels: 15 June

- Chapter 23 The Evening of 15 June in Wellington’s Sector

- Chapter 24 Wellington Reacts: From Midnight to Late Morning, 16 June

- Chapter 25 ‘The De Lancey Disposition’ in Context

- Chapter 26 The Approach to Battle: Sombreffe, Morning, 16 June

- Chapter 27 The French High Command: Assumptions and Orders, Morning, 16 June

- Chapter 28 Ligny: Afternoon and Evening, 16 June

- Chapter 29 Quatre Bras: 16 June

- Chapter 30 The Fiasco Involving d’Erlon’s Corps: 16 June

- Notes

- Plate section