eBook - ePub

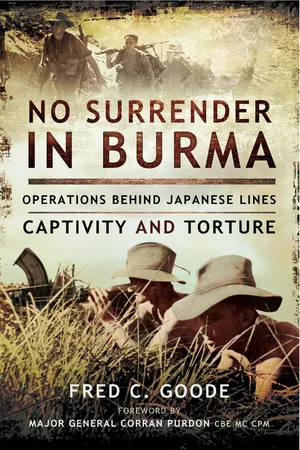

No Surrender in Burma

Operations Behind Japanese Lines, Captivity and Torture

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This British Commando's WWII memoir recounts his attempt to escape Japanese-occupied Burma and his harrowing experiences as a POW.

This is the extraordinary story of Lance Corporal Fred Goode, a British Commando stationed in Burma in 1941. Cut off behind enemy lines the following year, Goode walked 2,000 miles towards India and freedom, but was betrayed to Japanese forces only 20 miles short of his destination. Tortured by the infamous Kempeitai—Imperial Japan's military police—Goode was then sent to Rangoon's notorious Central Jail, where he remained a prisoner of war until Japan's surrender.Goode was one of fifty men sent to Burma to support and train Chinese forces fighting in Japanese-occupied China. With Japan's entry into World War II in December of that year, their mission expanded to include destroying airfields and taking bullion to India. When they were overtaken by enemy forces before crossing the Irrawaddy River, their commanding officer instructed them to split into four groups and head for India or Yunnan. Of the original fifty, only eight survived.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No Surrender in Burma by Fred C. Goode in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Bush Warfare School

I was a lance corporal in a party of one hundred Commandos sent to Burma from North Africa in September 1941. We had all volunteered for a special job; what, we did not know.

We had travelled first by sea to Ceylon, then on to Calcutta, and from there by French tramp ship to Rangoon. We stayed in Rangoon for two nights before boarding a train northward to the old Capital of Mandalay, from where we travelled by trucks up the Burma Road that links China with Rangoon. The journey took us nearly five hours around the twisting and winding bends, sometimes climbing over hills, sometimes going down into valleys. The engines of the trucks groaned against the hard climbing that was asked of them. Then suddenly we were upon a plateau with rising hills on either side. We continued on through the small town of Maymyo, and some way past the town we turned off the main road and followed a well-worn track until we came upon a clearing. On the fringe of the clearing bamboo bungalows were set out. That was our destination, the Bush Warfare School.

Other troops were here already and had prepared a meal for us. After getting our kit from the trucks and making ourselves comfortable in our new home we settled down for the night. All of us asked the same question. What were we doing out here? Not one scrap of information had been given to us from the beginning of the journey from North Africa. Four commissioned officers had travelled with us – two captains, Wingate and Brocklehurst, and two ‘one-pip’ lieutenants, Gardener and Lancaster – but any instructions from them came through the two sergeants with our group, Cobham and McAteer, Cobham being the senior. Breakfast would be at eight the next morning, and we were told to parade at nine, where we would be sorted out into two detachments.

Sleep came very easily that night as the long and tiresome journey had taken its toll upon us. Most of us made for our beds early as there was not much to do in the strange camp which, by the time we had got our kit sorted out, was in darkness.

At nine the next morning we formed up into two ranks with the two sergeants taking up positions in front. Shortly after, the four officers came. After the usual ‘present and correct’ from the sergeants, the two NCOs were told to take up posts away from us. Then the two captains called names out from sheets of paper they were holding. Captain Brocklehurst called for men to form up on Sergeant McAteer, and Captain Wingate called out men to form up on Sergeant Cobham. I was called by Captain Brocklehurst and so fell in on Sergeant McAteer along with the rest.

After the separation of the two detachments, Captain Brocklehurst told us that, as from now, we would be known as ME Detachment II, while Captain Wingate commanded ME Detachment I. The next thing was to get our kit sorted out so that we were all together in one bungalow. It was Friday and payday, after which we had the weekend to ourselves to explore Maymyo.

Monday morning began with PT at 06.30 hours, followed by breakfast, then parade at nine to be marched to one of the larger bamboo bungalows which served as a classroom. Here we were introduced to a man named Calvert. He was a captain in the Royal Engineers and was going to teach us about explosives and demolition in general.

Captain Calvert – ‘Mike’ to his friends – was a dark-haired, black-steely-eyed and flat-nosed man about five-foot eight-inches tall, with very broad shoulders. His appearance was as if he was almost square, as broad as he was tall. He talked to us about what we would be learning and what we would be doing, but he would not tell us why. He talked for nearly an hour, and in that time he had got the admiration and the confidence of everyone in the room, so much so that had he at any time said ‘Follow me to hell’ I am sure that every man there would have got up and gone without question, such was his impact upon all of us.

Our lessons from him would be twice a day, five days a week, with an examination on what we had learned, both written and practical on Saturday mornings. Our first lesson was to begin at nine o’clock the next day.

The next introduction was to two ‘one-pip’ lieutenants whom we had never seen before. Their uniforms looked very new, as if they had just been drawn from stores. The pips on their shoulders showed also that they had never had a button brush put across them, so we gathered that these two were really green to the service. Captain Brocklehurst introduced them as Mr Robinson and Mr Moore. Then came the first big surprise. These two officers were going to teach us all to speak and understand Mandarin, the standardised Chinese language. A wry smile spread over the captain’s face as he glanced along the rows of faces staring at him in sheer amazement.

Mr Robinson was something of a lah-di-dah sort of fellow, not very old, about twenty-two. He told us that he spent quite a good deal of time in China working with the Shell-Mex company. Mr Moore was an entirely different person. He was a little older, in his thirties, short and a little untidy, but his speech and manner were much more to our liking. He too had worked for Shell-Mex, but it seemed that he left the majority of things for Mr Robinson to say. It appeared to us that Mr Robinson had already assumed seniority.

Chinese lessons were to be undertaken twice a day, five days a week, beginning at eleven o’clock the next morning, with written and speech examinations on Saturdays.

After the final introductions and talks by our instructors, Captain Brocklehurst told us that we should now be formed into three sections, with an officer and sergeant in charge of each section. So, there and then, two senior corporals, Friend and Baker, were made up to sergeants. Two more junior officers were to join us at a later date to make up the full complement, we were told. (In fact, Captain Brown, the adjutant at the school, later joined us as the head of the third section.) Brocklehurst and Wingate were also promoted to majors, and the two ‘one-pippers’ to full lieutenants.

The first week went by with most of our work taking place in the classroom. We were getting on quite well with the Chinese language, and Captain ‘Mike’ Calvert was keeping us hard at work on different types of explosives and how best to use them.

We still could not find out for what purpose we were there, though many rumours floated about, as is usual in any of the services.

Sporting events such as football and hockey were arranged between units. Sometimes at weekends we went out on exercises. During these exercises we were instructed by Burmese, who taught us how to use the jungle and build rafts and small lean-to huts that would give us shelter in an emergency, how to make string and rope from bamboo, how to use the male bamboo for cooking-pots and so on, what grass is suitable for human consumption, what berries and plants and snakes and rodents we could eat, and if the worst came to the worst what type of tree bark would sustain us.

In October there were more promotions among the officers. Wingate and Brocklehurst were made colonels while Gardener and Lancaster were made up to captains. These sudden rises in rank had no effect on any of us, and we carried on with the jobs that we were given.

Towards the end of October there was, however, a rift between the two colonels about who was the senior. Brocklehurst had been an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, so even to us that made him the senior. This, we understood, upset Wingate, and he suddenly left. We heard rumours that Wavell had recalled him to New Delhi and put another officer in his place.

Things went on as normal without Wingate. ‘Mike’ Calvert was putting us through some very rigid exercises, and so were the two Chinese-language teachers.

Then, about the middle of November, we got measured for civilian clothes and also had our photographs taken – but we still could not find out why.

Chapter Two

To the Thai Frontier

It was a misty damp Monday morning, December 8th about eight thirty, as we emerged from our bamboo huts to make our way to breakfast. Someone somewhere shouted, ‘The Japs have bombed Pearl Harbor!’

‘Pearl Harbor?’ I asked, ‘Where the hell is that?’

‘I don’t know, but it means that the Yanks will be in the war with us now,’ someone answered.

After a hurried breakfast and plenty of chatter we all gathered around one of the wireless sets that we had for communications. There we heard the President of the United States make his speech to the people of the USA, saying that they were at war with Japan.

Overnight the whole situation had changed. Instead of the utmost secrecy surrounding us, everything was now out in the open. We learned that the original intention was for us to go into China as civil advisers or technicians to assist the Chinese in the war against the Japanese in an effort to try to keep them a little more occupied in that area. With the altered situation we were told that we could proceed across the frontier in our own uniforms and trucks marked with the Union Jack flags. The Australian contingent who were also in training with us were the first to move out. They were destined for the Canton region as they had been learning Cantonese. It was well after Christmas when we moved to the southern Shan state of Burma to set up a base at a town called Taunggyi.

Things were really looking black for us. Hong Kong had fallen on Christmas Day, and the Japanese had swept down the Malay Peninsula. The battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse had been sunk by Japanese planes, and the ‘impregnable’ fortress of Singapore had fallen. The Japanese had also taken Indochina and were well into Thailand. Meanwhile, back in North Africa Rommel had taken Tobruk and was pushing up the desert towards Alexandria.

We left our heavy kit back at the school, and only carried necessities. Our lorries had been packed to capacity with all types of ammunition and explosives, and we moved into bamboo bungalows just outside the town of Taunggyi, where we made a supply base. After a couple of days’ rest we set off in the lorries, leaving two men to look after the base, and headed in a southeasterly direction towards a small town called Kentaung. Here we rested for one night, then we travelled further southeast to a very small town called Mong Hsat. Here we had to leave the lorries, as the motor road ended. We picked up mules to carry our gear, and also bid farewell to Captain Gardener and his section, as they were moving on to the southern tip of Indochina.

Fred’s march through Burma.

From then on we were on foot, leaving behind another two men to make another supply base. We moved out of Mong Hsat with just enough supplies loaded on the mules. We marched until well into the afternoon before making camp for the night.

Around the camp fire and after our meal, the Colonel gave us our instructions for the following day. Beginning at dawn we were to split up into parties of five or six, with two Chinese muleteers and six mules. The parties were to set out at intervals of four hours. Our party consisted of Corporal Robert ‘Jock’ Johnson, Private Harry ‘Ginger’ Hancock, Private Thomas Morgan, Lance Corporal William Bland, and me. We were given a reference point on the map, marking an old Buddhist temple about sixty miles from the Thai border, which, without any mishap, should take three days of marching to reach. There we would all collect and wait for everyone to arrive. Our party was the third away, setting off at about two thirty in the afternoon.

We marched at a comfortable pace with the mules bringing up the rear. We took turns at going forward, having two men in front, one link man and two at the rear in close contact with the mules. It was left entirely up to Jock to call the halts, except when we made camp for the night. Then the two front men picked the best place where we could not only get water for cooking and cleaning, but at the same time be under cover.

Each one in the party knew where the rendezvous was, so that should anything happen, the others could carry on. We saw signs left by those ahead of us that told us that we were on the right track, but we did not always stop where they had made camp. In some instances we were a few hours ahead.

It was midday when we came to the Salween River. The only way across was by a large bamboo raft that would take three men with their gear plus one mule.

The raft was handled by two natives. One of them paddled until it was well into the current, while the other, on the opposite bank, pulled on a thick bamboo rope tied to the raft.

This was repeated about six times before all our kit and the mules were across. We did not hang around as we knew we could be spotted by any passing aircraft.

After leaving the river and being very pleased with ourselves at crossing without trouble, we camped deep into the thickest jungle, with the knowledge that we would, bar anything going wrong, reach the temple by noon the next day.

It was a little after that time that we were met by a couple of the men who had taken a quiet stroll out of the camp to meet us, ‘just in case,’ they said, ‘we had suffered any casualties.’

We found on arrival at the temple that we had been most fortunate with our mules who had behaved very well in comparison to the other parties. We heard that some of the mules had just bolted at the river’s edge off into the jungle, while others, once their loads were taken off, would not have them back on again. One mule flatly refused to go on the raft, so he and his handler were forced to swim the river.

Of the original fifty other ranks, we had now got three officers and twenty five men. We had left two at Taunggyi, two at Kentaung and two at Mong Hsat and, of course, Captain Gardener’s section.

We rested for two whole days at the temple. Dawn was just breaking when we set off on the third day with two scouts in front and two men bringing up the rear.

At about four in the afternoon the two forward men reported some movement of what looked like uniformed troops. The column was halted. The colonel, Sergeant McAteer and two men went forward. It seemed that the colonel had expected this, as we had been told that some Chinese troops were being sent to this area.

After a short while the colonel and others returned. Under his orders we moved on for about another five miles before making camp. The colonel wanted no friction with the Chinese troops, as they had a reputation for stealing kit and equipment.

We broke camp the next day, and except for short stops marched for another two days until finally reaching our objective, which was no more than a spot on the map, just six miles from the Thai border.

Before making camp, the colonel had us unload all the mules, kept only six and sent the rest away with the muleteers.

We made the camp well and truly camouflaged from the air. We were within strolling distance of a beautiful clear running stream with wild peaches, bananas and other tropical fruits, and exotic tropical flowers growing all around it. It gave one the feeling of paradise. Had it not been for the job in hand it could well have been paradise, with the beautifully plumaged birds and the antics of the gibbon apes as they swung about in the trees to our amusement.

We then had two days of rest, lounging in the sun and swimming in the stream. On the third day, at about ten in the morning, the colonel called us all together. A sand table had been made with two large mounds, which represented hills. The colonel pointed out that these two hills were our objectives for an attack. ‘We shall have to march six miles to the border,’ he said, ‘then about two more miles to get near enough to observe our targets, making our assault on them in the early hours of the morning. They are two gun emplacements that cover the whole of an escarpment and are manned by both Thai and Japanese troops. To get there well before dusk ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Bush Warfare School

- Chapter 2: To the Thai Frontier

- Chapter 3: The Bombing of Taunggyi

- Chapter 4: A Rich Grave

- Chapter 5: A Trap Well Laid

- Chapter 6: Race to the Irrawaddy

- Chapter 7: The Separation

- Chapter 8: The Return of Lacey

- Chapter 9: Father McGovern

- Chapter 10: Attack by Bandits

- Chapter 11: The Confrontation

- Chapter 12: A Tempting Offer

- Chapter 13: On to Tengchong

- Chapter 14: Fortress Sima

- Chapter 15: Betrayal in Sadon

- Chapter 16: Ruthless Barbaric Animals

- Chapter 17: Torture in Myitkyina

- Chapter 18: Rangoon Central Jail

- Chapter 19: Cholera and Bombs

- Chapter 20: Forced March to Freedom

- Postscript

- Notes