- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An autobiography by a British army soldier in which he provides intimate details of his capture, survival and escape from prison camps during WWII.

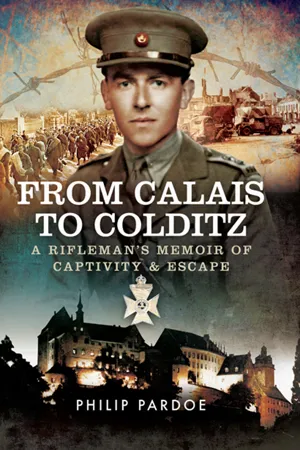

From Calais to Colditz has never been published before but readers will surely agree that the wait has been worthwhile. Author Philip Pardoe was a young platoon commander when his battalion were ordered by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to defend Calais to the last man and so distract German attention from the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Forces at Dunkirk. After an intense four-day battle, the survivors were subjected to a grueling twelve day march towards Germany. There followed incarceration in a succession of POW camps during which the author succeeded in escaping twice, both over the wire and by tunneling, remaining at large on one occasion for twelve days. These exploits qualified him for a place in the notorious Colditz Castle, the supposed escape-proof camp. The descriptions of his colourful fellow prisoners, their captors and their extraordinary experiences are as good as any of the previous accounts and in many respects more revealing. How fortunate it is that From Calais to Colditz can now be read by a wide audience.

From Calais to Colditz has never been published before but readers will surely agree that the wait has been worthwhile. Author Philip Pardoe was a young platoon commander when his battalion were ordered by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to defend Calais to the last man and so distract German attention from the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Forces at Dunkirk. After an intense four-day battle, the survivors were subjected to a grueling twelve day march towards Germany. There followed incarceration in a succession of POW camps during which the author succeeded in escaping twice, both over the wire and by tunneling, remaining at large on one occasion for twelve days. These exploits qualified him for a place in the notorious Colditz Castle, the supposed escape-proof camp. The descriptions of his colourful fellow prisoners, their captors and their extraordinary experiences are as good as any of the previous accounts and in many respects more revealing. How fortunate it is that From Calais to Colditz can now be read by a wide audience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Calais to Colditz by Philip Pardoe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Before Calais

No-one who paid a casual visit to the 2nd Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, billeted in Dorset in the spring of 1940, would have noticed any undue activity or preparations for going into motion. The Blitzkrieg had burst upon France in April and German divisions, having broken through, were pouring toward the Channel coast; the Battalion, however, seemed as far away from the war as in Tidworth days and not an enemy bomber disturbed the routine of our weekly training programmes.

I had joined the Battalion from Chisledon early in March and was posted to Number 9 Platoon, the Scout Platoon of ‘C’ Company. Maurice Johnson was commanding the Company into which he had infused a remarkably cheerful spirit. Although gruff outwardly to men and officers alike, he was much respected and liked by the men if a little too insensible to the comfort and feelings of some of his officers for their full approval.

Everard Radcliffe, his second-in-command, was an excellent counter-balancing influence. He was exceptionally gifted and artistic, loathed discomfort and had the happy knack of getting his own way. He was the only married one of us and lived in Shillingstone. The other platoon commanders – Peter Parker, Pat Sherrard and I – lived with Maurice in a comfortable cottage in Child Okeford, where the Company was billeted.

We spent those lovely spring days training either by platoons or as a company and on two or three occasions we had battalion exercises. Few men knew their weapons really well, owing to lack of firing practice, and battle drill was a word as yet unknown but none of us doubted that we were one of the best trained battalions in the army and quite a match for anything the Germans might have.

One evening, after dining well, we had just gone up to bed when a rifleman arrived on his motor bike with a message for Maurice. We gathered in the dining room – Sergeant Major Childs had also appeared from somewhere – and heard the news. The Battalion was to be ready to move with war loads by midnight. It seemed probable that this was the preparatory move before embarkation. It was what we had been anticipating since 3 September.

We all felt slightly dramatic. Most of us felt that this period of make-believe was over and that this was the real thing. We pretended to be even more pleased than we were in our fear of appearing unenthusiastic for action. We passed the port hurriedly round and then I got into my car to visit Everard.

Nobody appeared to be at home in his cottage and, as I was groping round in the darkness of the hall, he and Betty came in the front door after an evening stroll. I broke the news to them breathlessly and with little tact. Everard made no attempt to disguise his feelings of dread. For him the sword of Damocles had at last fallen and he and Betty were to be parted.

I hurried back, told my servant to pack my things and went down to the Company Office. Loading carriers in pitch darkness was far from easy. Bren guns, Boys rifles, rifles, tripods, ammunition, Verey light pistols, aiming lamps, hand grenades, camouflage nets, ration tins, water cans, tools, maps, concertina wire, tarpaulin, anti-gas equipment – all had their allotted place. We had practised loading and everyone knew his job and, by 2330 hours, all my carriers were ready to move. Only my Sergeant Dryborough-Smith and one or two men who had been to a dance in Sturminster Newton were late. Dryborough-Smith was a big tall fair-haired regular with much service in a chequered career. He had been to a public school and went to Sandhurst as an ‘A’ cadet but got sent down and was usually ‘on the provost’. He had a bit of the bully in him and was not liked, if much feared, by the men. Our relations were strained but superficially good. I respected his efficiency while disliking his methods and we avoided quarrelling. That night I suspected him of being deliberately late but said nothing.

The news of the move had spread through the village like wildfire. The riflemen had endeared themselves to the local inhabitants in an extraordinary way and, now that we were leaving, the girls came to say goodbye to their boyfriends and there was much sobbing and kissing. Once the order arrived we were soon ready to leave next morning at 0630 hours. We went to bed and snatched a hurried sleep. I woke early, bundled all my belongings which I did not want to take into my car, drove to the Glazebrooks’ house and scribbled two notes – one to her and one to my family.

We left Child Okeford punctually. The Battalion moved in two columns, one for wheeled and one for tracked vehicles. Mike Sinclair commanded the latter. We received our route to Ware [near Hertford] via Salisbury, Newbury and Reading.

Despite the early hour the whole village was up to wave goodbye – with many in tears. As we were passing through Shillingstone, I saw Betty standing alone looking miserably unhappy. She had just said goodbye to Norman [Philips] for the last time. I waved to her but she never saw me. I felt sad as I realised what our parting meant to others and yet elated at the thought of the adventure that lay ahead. The wind blew fresh in our faces and the dew was still on the grass. It was good to be doing something at last.

The drive was uneventful. About mid-day we halted near Newbury, opposite an aerodrome, to fill up with petrol. Something had gone wrong with the ration truck which had not yet appeared so we bought some meat pies and sausages from a canteen nearby. A string of traffic passed us – race-goers on their way to the Spring Cup. Wonderful memories flashed through my mind and made me sad for a while.

We moved on again and in every town crowds thronging the streets waved to us as we crashed through. They were giving us a great send-off. To them we were the reassuring answer to the bad news from France. We waved back proudly at first but soon grew weary of this.

By the time we approached Hertford it was getting dark. We were tired and hungry. Apart from two punctures to my motor bikes all had hitherto gone well but here I found one carrier was missing. It caught me up after a few minutes and I learnt that the exhaust pipe had set the camouflage net on fire but little damage was done.

A guide led us in pitch darkness to our billet in Ware which was very bad – an old disused house with no lights or water, many floor boards broken and strewn with shattered glass from the windows. We were all tired and bad tempered and consequently a bit snappish. I was very glad to get into my flea-bag for the night. We were up early next morning and, after gathering my platoon and telling them to see to the maintenance of their vehicles and weapons, Maurice and I left for a tactical reconnaissance near Rayleigh. The Company were to join us there later in the day.

We were told that the Germans were expected to attempt a landing on the coast at any time and perhaps to drop parachutists. We were to reconnoitre all roads in the district which led to likely vulnerable points and liaise with the Pioneer Corps who had prepared a number of road blocks.

The Company arrived about tea time and was billeted in a girls’ school with both officers and men sleeping on the floor in different rooms. The officers of all other companies were billeted centrally and feeding and living very much more comfortably; I felt this was a great injustice.

The next few days were spent with our NCOs reconnoitring the road blocks and vulnerable points in our area. I celebrated my 21st birthday by being called at midnight and told to stand by from 0200 hours onwards, as the Germans were expected that morning. Visions of scoring ‘first blood’ that day were disappointed. It was one of many false alarms. During the day I got several letters and birthday presents, including a gold compass from Mum, a photo from Flick, and a dry fly line from Dad which I sent straight home! The fishing prospects did not look good. Best of all a large box of chocolates arrived from Fortnums which we quickly dealt with.

The next day we were once more on the move – a short drive this time through Bury St Edmunds to Fornham Park. Apart from one of my carriers knocking over a telegraph pole there were no mishaps on the way. Fornham Park was a distinct improvement with a large house, in which some sapper officers were billeted, and lovely grounds which must have provided a good pheasant shoot. With the Battalion I slept under canvas in ideal weather to the sound of the nightingales singing in my ears.

The officers messed together in a marquee and for me this was the first time we had all been together during the war. By day we reconnoitred the roads in the Harwich areas – a raid was expected on the port. We were at very short notice to move and had little chance to get away. One evening, after a hot and tiring day, we were asked to go over to a private school next door to bathe in their swimming bath. It was wonderfully refreshing. The washing question was difficult. I used an old woman’s house in Rayleigh, but the men were very short of water until a diviner arrived and sank an artesian well which threatened to flood the area.

One day Martin, Peter Parker and I decided we needed a really good dinner. We would go into Bury and order roast duck, Bollinger ’28, etc. And we persuaded the Colonel, Euan Miller, to try to get us permission to go to Newmarket races next day. We drove into the town and went first to the hairdresser. As we emerged licking our chops at the thought of our dinner, the Provost Corporal drew up on his motor cycle: ‘All ranks return to camp at once.’

We managed to secure a taxi and on the way back picked up a number of riflemen including Sergeant Dryborough-Smith. The camp was seething with activity – tents being struck, vehicles loaded in record time and even Tucker was busy packing my valise. I changed from Service Dress into Battle Dress putting on plenty of warm clothing. My platoon was present and ready to move by 2000 hours.

At dinner I heard that we were to move at 2330 hours. Everyone was in a state of suppressed excitement. Humour had it that this was no invasion scare – it was the real thing. After dinner Tony Turner came round to see me. He was in tears and very agitated. He managed to stammer out that Tony Stallard, the MO, had forbidden him to come with us as he suspected a mastoid in his ear. Tony has been to see Godfrey Cromwell and the Colonel and caused a dreadful scene but both were adamant. He swore it was the worst blow fate had ever dealt him. I was very sad and tried to comfort him by saying he would probably join us in a week. He left me in tears.

All was now ready but there were still two hours to go. The Company sat round in a circle and sang all the old favourites. It was a lovely night. Just before 2300 hours we started up the carriers and moved to the forming up position at the Park gates. Maps were issued and the route given – Newmarket, London, Winchester, Southampton. Our doubts were finally dispelled. It was France at last.

First the wheeled vehicles, then the carriers moved off – 20 yards between vehicles and 200 yards between sections. The DR [Despatch Rider] of each section kept in touch with the section in front and did ‘traffic control’. With dimmed lights progress was slow and it seemed a long time before we reached Newmarket, 20 miles off. I recalled the last time I was there, when Norman, Bill Fyfe and I flew up from Tidworth for the ‘Guineas’.

Every two hours the column halted. On the first such occasion an order came back that all lights were to be extinguished. It was intended to refer only to the actual period of the halt but this was not made clear. So instead of being guided by a long string of tail lights, like a luminous string of beads, we could only see ten yards ahead. This was very dangerous for the DRs. By 0330 hours I was feeling tired. The road appeared straight forward so I dozed off to sleep. I woke up some time later to find we had stopped in a country lane. My 10 carriers were drawn up behind but there was no sign of the column.

My DR, Perry, thinking he saw the next carrier turn off, had led my whole platoon up a side road and had just realised his mistake. I heard the noise of some carriers approaching and next minute a whole section swept round the corner straight towards us. Perry was standing in the middle of the road with no lights on and only just got out of the way in time. I flashed my torch and they pulled up having made the same mistake as us.

We all hustled back to the main road, where we joined the Brigade HQ Group, whom we passed and at the next halt regained our position in the column. As I was trying to sort out the muddle I was hailed in broad Lancashire and there was Smith, Grismond Davies-Scourfield’s servant, who had looked after us at Blandford Camp. I had not seen him since and we were both very pleased to meet. He was a great character and I was very fond of him.

We continued the journey. I changed my drivers and alternately drove a carrier, a motor bike and slept. We were short of reserve DRs and Filkins had to drive the whole way unrelieved – a great feat. Passing through London it started to rain. I was on a motor bike at the time luckily wearing my mackintosh but everything and everyone got soaked. We filled up with petrol in London and stopped for breakfast on Hertford Bridge flats about 1030 hours. We were just by Roberts’ gallops where I used to train Grecian Isle for the Sandhurst point-to-point. The rain stopped and we soon dried out as we rattled along that Tidworth-London road I knew so well.

By the time we were approaching Southampton the DRs were very exhausted. Perry went to sleep and drove into the ditch – luckily without doing any damage. Moffat, the Battalion Motor Transport [MT] Sergeant, did the same and had to be taken to hospital with a cut knee. That was the only bad accident on the whole journey. In Southampton some immaculate Staff Officers relieved us of our maps and some kind people gave us hot tea and buns which were very welcome. The drivers took the vehicles off to be loaded while the remainder of the Battalion was directed to a rest camp for a wash and a hot meal.

John Christian and Mac McClure were waiting there. They had come over from the depot to see us off. It was good to see John again after so long. Together with Martin Gilliat [later Lieutenant Colonel Sir Martin Gilliat, GCVO, MBE] and Norman we went off to have tea in a café. There we bought plenty of chocolate and ate a proper hunting tea of scrambled eggs and bacon. Norman rang up Aunt Margaret to say goodbye. I wondered whether to do the same but decided it would be too painful. So I sent off a wire saying ‘Cook the ducks to-night’. It was a prearranged code which Dad had used in the last war, for exactly the same purpose, before embarking for France.

We returned to the camp and the Battalion formed up wearing full equipment to march through the town to the boat. It was a moving experience. Crowds on the pavement cheered as we went by and here and there a handkerchief was raised to damp eyes. These people, mostly women, saw war stripped of its glamour and knew from experience the tragedy it entailed. Some had sons or husbands in the Battalion and were wondering how many would return.

But to these people I scarcely gave a thought. I was filled with pride and gratitude that I was going into action with the Battalion I loved, just as my father had done in the last war. Here at last was an opportunity to pay back something that I owed to my regiment and country. We passed a field where a cricket match was in progress. Few of the players bothered to give us a glance. But, far from resenting this, I felt sorry for them that they had not a similar opportunity and so could not share my feelings. A number of riflemen from the depot, mostly old and unfit, kept pace with us, chatting and joking. ‘Good luck, mate, wish I were in your boots.’ They really meant it.

At the docks the roll was called and the Battalion reported present. In single files we trooped on board. There were three ships waiting – one for us, one for the Rifle Brigade who had come down from Essex and one for our transport. The other two regiments forming our brigade – the Queen Victoria Rifles [QVRs] and the 1st Tank Regiment – had left the day before and were already across the Channel. Our weapons were stacked on deck and Maurice told me to post a sentry on them. It was only just in time, for in a few minutes I met Norman who had lost a Bren-gun somehow. I felt very smug. All Ranks were then assembled with lifebelts strapped on and we were told where to go on the ‘Alarm’ or ‘Abandon Ship’. I visited my platoon in their quarters below. They were very cramped but no-one seemed to mind the discomfort.

Most of the officers bedded down in the smoking room but a few had cabins. I thought I had discovered an unoccupied one until Puffin [Major O.S. Owen] arrived and turned me out. Tucker as usual had disappeared. He was a young militiaman whom I had only known a few weeks. He was obviously unsuitable as a servant, but in the recent busy days, I had found no time to select another from the DRs. At last I got my things together and went into the dining room. We had a first class meal with two double whiskies costing only half a crown. I turned in early with the rest under way for Dover.

Called at 0400 hours I dressed hurriedly, not knowing where we should find ourselves, and once on deck recognised the famous white cliffs. We were lying just off the harbour. I was Orderly Officer and, having seen tea issued to each company, inspected the Anti-Aircraft Posts. One had no tracer ammunition and another only two magazines which would have lasted half a minute.

Down below breakfast was being served – the last proper meal for several weeks and the last eggs and bacon for years. But we never gave this possibility a thought. Presently the boat put into Dover harbour and a number of people sent off letters to their homes. Unfortunately I never thought of this until too late. In higher circles great decisions were being taken and the Brigadier, Claude Nicholson, was receiving his final orders from the War Office.

About mid-day we got under way aboard SS Royal Daffodil for Calais. The three transports were escorted by four destroyers, zig zagging in front and on both flanks. Overhead the odd fighter roared pas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Before Calais

- Chapter 2: The First Day – 23 May

- Chapter 3: The Second Day – 24 May

- Chapter 4: The Third Day – 25 May

- Chapter 5: The Last Day – 26 May

- Chapter 6: The March

- Photo Gallery

- Chapter 7: Early Days of Captivity

- Chapter 8: Olympia

- Chapter 9: A Summer Holiday

- Chapter 10: A Long Weekend

- Chapter 11: Colditz

- Chapter 12: Liberation