- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Great War helped China emerge from humiliation and obscurity and take its first tentative steps as a full member of the global community.In 1912 the Qing Dynasty had ended. President Yuan Shikai, who seized power in 1914, offered the British 50,000 troops to recover the German colony in Shandong but this was refused. In 1916 China sent a vast army of labourers to Europe. In 1917 she declared war on Germany despite this effectively making the real enemy Japan an ally.The betrayal came when Japan was awarded the former German colony. This inspired the rise of Chinese nationalism and communism, enflamed by Russia. The scene was set for Japans incursions into China and thirty years of bloodshed.One hundred years on, the time is right for this accessible and authoritative account of Chinas role in The Great War and assessment of its national and international significance

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Japan sees an opportunity

In the summer of 1914, Japan saw an opportunity. On 15 August, a week before officially declaring war on Germany, the German ambassador in Tokyo, Arthur Graf von Rex (who had been trying to persuade Japan to align itself with soon to be victorious Germany) was presented with a Japanese ultimatum demanding that Germany withdraw all its warships from East Asian waters and hand over the German concession in Jiaozhou Bay [Kiaochow] (Shandong province) to Japan, for ‘eventual’ return to China. Receiving no answer to the demands, on 23 August, Japan declared war on Germany and on 2 September 1914, 23,000 Japanese troops landed on officially neutral Chinese soil about 100 miles north of Qingdao [Tsingtao, or, in German, Tsingtau], and marched inland. Coming late to the European occupation of Chinese territory, Germany had occupied the bay in 1897 on the pretext of reprisal for the murder of two German Roman Catholic missionaries in the south of Shandong province and ‘leased’ 552 square kilometres of territory around the bay, which provided a fine natural harbour for the German Far East naval squadron.

The German Empire came into being in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War; the following year, King Wilhelm I was proclaimed Emperor at Versailles. His ambitious grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, was determined to catch up with the other European powers such as Britain, France and Russia, which had been exploiting China for half a century. He believed in the superiority of European over Asiatic peoples whom he saw as a threat to civilisation. He coined the phrase ‘Yellow Peril’ (gelbe Gefahr) and saw himself leading Europe in a campaign to defeat it. He had a dream in which he, as St Michael, led the other European nations, all dressed as women, in this campaign. When a newly industrialized and aggressive Japan inflicted a humiliating defeat on China in 1894–5, a further rival was added to the powers in the Far East.

Foreign missionaries in China, often stationed in remote villages far from consular protection, were frequent victims of anti-foreign violence. When the two German missionaries were murdered on the evening of All Saints Day 1897, probably by members of a local peasant secret society, the event was sufficient to provoke a response from Germany which seized the fine natural bay on the north of Shandong province. The seizure and occupation of Jiaozhou Bay was achieved through yet another of the humiliating ‘unequal treaties’ forced upon China which provoked considerable resentment and whose abolition was to be a major topic at the Versailles Peace Conference.

SHANDONG – CHINA’S KEY WAR AIM

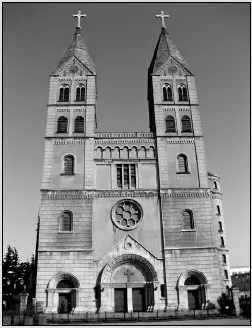

Tsingtao was the heart of Germany’s enclave in Shandong, the birthplace of Confucius. Its recovery was of great symbolic importance and was to become one of China’s key war aims. Its civilian population in 1914 was about 55,000 (of which 3% were German); it has grown to the 2.7 million of Qingdao now. The construction of St Michael’s Cathedral was held back by Japan’s capture of Tsingtao and it was not completed until 1934. It was defaced and its clergy arrested during Mao Zedong’s era, but it is now an active church again.

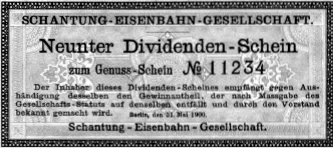

Railways, mostly foreign, were deeply resented, as they eliminated porterage jobs, disturbed ancestral graves, sequestered farmland and put China in hock. The Shandong Railway (SEG), founded in 1899, financed by German banks and investors, began paying dividends in 1905 (3.25%) rising to 7.5% in 1913.

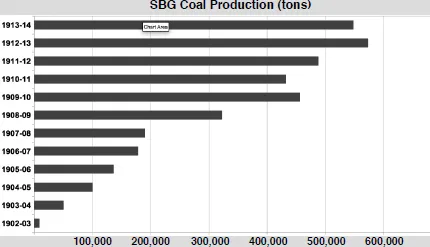

The Governor of Shandong tried, unsuccessfully, to buy shares and get board representation. One of SEG’s main purposes was to carry coal from the mines of another German company, SBG, needed for the East Asia Squadron, based at Tsingtao.

SBG’s output rose steadily, but much of its production was unsuitable for bunkering and was uneconomic because of the lower costs of small Chinese competitors, which relied more on human labour than expensive machinery. Its poor financial record led to its being taken over by SEG.

Tsingtao beer (no longer branded with a swastika) is marketed in supermarkets in Europe and America – a peaceful reconquest of the former colonizing powers.

NOTES: population, SEG and SBG; Imperialism and Chinese Nationalism by John Schreker, Harvard UP, 1971 and The Dragon and The Iron Horse RW Huenemann, Harvard UP, 1984. Coal production; Diplomatic Relations between China and Germany since 1898, by Feng Deng Diang, published in 1913.

At the mouth of Jiaozhou Bay, stood the town of Qingdao, later described as ‘one of the most fashionable watering-places of the Orient’. Originally a small fishing village, it was expanded by German occupation, into a model colonial city, redolent of towns and cities in the home country. There were familiar sounding streets, such as Friedrichstrasse, Wilhelmstrasse and Hohenloe Weg, lined with solid German-style buildings. There was a handsome Protestant church, there were schools, hospitals and a yacht club. An imposing railway station served the new Shandong Railway needed to exploit the province’s mineral wealth, particularly coal to fuel the expanding German navy in its Far Eastern activities. High above the town was a magnificent residence for the governor who was a senior naval officer, underlining the naval significance of the concession.

Electrification, sewage systems and clean drinking water were installed throughout the town, a rarity in China at the time. Banks and other commercial establishments were set up and many Chinese built businesses and houses there attracted by the secure and well-managed environment. Sun Yat-sen, main architect of the Chinese Republic remarked in 1912, ‘I am impressed. The city is a true model for China’s future.’ The Tsingtao Brewery, founded in 1903 under joint Anglo-German ownership but German management, produced a beer which is still enjoyed all over the world. Its early advertisements carried the swastika, an auspicious Buddhist symbol widely used in China before both its direction and significance were turned upside down by the Nazis.

Ships of the British Navy’s Pacific squadron made ‘courtesy visits’ to the German East Asia naval squadron in Qingdao: in 1913, HMS Monmouth and her crew were welcomed there, and in 1914, HMS Minotaur, Admiral Jerram’s flagship, called in. When the German aviator Günther Plüschow arrived in the spring of 1914, on the day of his arrival he watched a ‘big football match between German sailors and their comrades from the English flag-ship Good Hope’.1

The background to Japan’s engagement was complex, involving a series of crossed messages. The German Minister in Peking, Baron Ago von Maltzan later to serve as Ambassador to the United States, seems to have been trying unsuccessfully to discuss the future of Germany’s concession in Shandong and its coal mines (of tremendous interest to coal-poor Japan) with the Chinese authorities and perhaps hand them back, whilst frantic messages were sent backwards and forwards between Peking, Tokyo, London and Washington.

On 3 August 1914 the American chargé d’affaires in Peking, John Van Antwerp MacMurray, reported that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs had asked the Americans to try and make the belligerent European nations undertake not to engage in hostilities on Chinese territory.2 On the very same day, the British Ambassador in Tokyo, Sir William Conyngham Greene, reported that, with reference to the Anglo–Japanese Alliance (1902, 1905, 1911) which guaranteed mutual support in the face of threat, he had been assured that the British could ‘count on Japan at once coming to the assistance of her ally with all her strength, if called upon to do so, leaving it entirely up to His Majesty’s Government to formulate the reason for and the nature of assistance required’. However, the eventual Japanese landing on 2 September was entirely decided by Japan, with no reference to or consultation with His Majesty’s Government.

Two days earlier, 1 August, the British Foreign Minister, Sir Edward Grey, had informed the Japanese Ambassador in London, Katsunosuke Inoue, that he ‘did not see that we were likely to have to apply to Japan under our Alliance’ for the British Foreign Office was narrowly preoccupied with British possessions in Asia and had no thought for German possessions in China.

The only way in which Japan could be brought in would be if hostilities spread to the Far East, e.g. an attack on Hong Kong by the Germans, or if a rising in India were to take place . . . but it might be as well to warn the Japanese government that in the event of war with Germany there might be a possibility of an attack on Hong Kong or Weihaiwei when we should look to them for support.3

Messages were certainly crossing, for the American Ambassador in London, Walter Hines Page, reported on 11 August that, far from accepting that help was not needed, Sir Edward Grey had been informed that ‘Japan finds herself unable to refrain from war with Germany. . .’4 On 7 August, Britain, having declared war on Germany on 4 August, requested that ‘the Japanese fleet . . . hunt out and destroy the armed German merchant cruisers who are now attacking our commerce.’ Japan, however, saw the chance to take things further and on August 9, the Japanese Foreign Minister, Baron Katō Takaake, informed Sir William Conyngham Greene in Tokyo that: ‘Once a belligerent power, Japan cannot restrict her action only to the destruction of hostile enemy cruisers’ and suggested that the best way to destroy German maritime activity was to attack Qingdao as ‘destroying the German naval base at Jiaozhou [Kiaochow] would provide the casus belli to bring the Alliance into effective operation.’

The British started to backtrack rapidly, asking that Japan ‘postpone her war activities’ with a further message from the British Ambassador in Japan, ‘Great Britain asks Japan to limit its activities to the protection of commerce on the sea . . .’

German defences

The territory in question around Jiaozhou Bay was not well defended for the Germans had never anticipated a serious military challenge. However, on 4 August, after an announcement of ‘the danger of war’ six days earlier, the inhabitants of Qingdao learned that ‘the die was cast in Europe!’ but, as Günther Plüschow wrote, ‘Of course, no one for a moment thought about Japan . . .’

On 15 August, the Governor of Qingdao, a naval officer, Captain Alfred Meyer-Waldeck, responded to Japan’s demands to ‘withdraw the German warships at once from Japanese and Chinese waters’ and to ‘surrender the whole protectorate of Qiaozhou forthwith’ by referring to ‘the frivolity of the Japanese demands’ which ‘admit but one reply’.5 By this time, the small number of German troops stationed elsewhere in China, including those in Tianjin and the German Legation Guard in Peking had ‘quietly slipped away’ and ‘headed for Qingdao’, to join volunteers from Shanghai in the defence of the German concession.6 The Shanghai contingent included five musicians from Rudolf Buck’s Town Band, seriously compromising Shanghai concerts. The Times correspondent G.E. Morrison, belittling the Japanese military achievements, scornfully referred to Qingdao as ‘a weakly defended fort garrisoned by an untrained mob of German bank clerks and pot-bellied pastry-cooks.’7

At the outbreak of war, the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau of the Far East naval squadron, commanded by Vice Admiral Count Maximilian von Spee, had, in fact, left the threatened territory in order to avoid being trapped there. Their intention was to try and reach Germany, but both were sunk by the British Navy in the Battle of the Falklands on 8 December 1914. Von Spee and his two sons were killed in the action.

A remaining light cruiser, the Emden, had also left Jiaozhou Bay to avoid being trapped in the harbour and was later to cause terrible devastation to Allied shipping in the Indian Ocean. She captured some two dozen merchant ships, sinking many of them before moving towards Penang where she sank a Russian ship and a French destroyer.

The remaining ships in Jiaozhou consisted of a torpedo boat, four gunboats and an elderly Austro-Hungarian cruiser, the Kaiserin Elisabeth, and, as far as troops were concerned, the Germans had infantry, a cavalry company of 140, military engineers in charge of machine guns and field artillery and volunteers from elsewhere in China, perhaps amounting to 183 officers and nearly 5,000 other ranks.8

Because it had always been assumed that any serious attack on the Shandong peninsula would come from the sea, there were a number of batteries along the coast protecting the bay and a major fort with four 280mm guns on Mount Bismarck, facing out to sea. To the landward side where the Germans assumed there lay no serious threat from the Chinese, they nevertheless set up two defensive lines of fortifications on the hills behind Qingdao, one with forts and batteries on Moltke Hill and Iltis Hill, backed by a redoubt line with trenches, ditches and barbed wire, the other, further inland, along the Hai River to the northern side of the peninsula. These inland defences were mainly built after 1908 when a British Military Survey had declared, ‘It would appear that the Germans do not intend to make Qingdao an impregnable fortress. In its present state it is probable that it would speedily fall to the attack by a land force of suitable strength, supported by a squadron of first-class armoured cruisers.’9

In the defence of Qingdao, the Germans had proposed to rely upon its own cruiser squadron as the first line of defence, a defence which was lost when Vice Admiral von Spee sailed away to avoid being trappe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits

- Introduction

- 1. Japan sees an opportunity

- 2. New China, the ‘infant republic’

- 3. Japan: not playing straight

- 4. China in wartime, 1914–1916

- 5. The Chinese Labour Corps: Yellow ’eathens are ’elping out in France

- Photo Gallery

- 6. Spies and Suspicions

- 7. A crucial year of chaos and decisions: 1917

- 8. After the war, the disappointment

- 9. Anatomy of a Betrayal: the interpreter’s account

- 10. China’s reaction

- Appendix 1: Chronology of Recent Chinese History

- Appendix 2: Key Personalities in the War

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Betrayed Ally by Frances Wood, Christopher Arnander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.