- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Napoleon's Infantry Handbook

About this book

What did Napoleon's soldiers carry in their backpacks? A unique reference that paints a detailed picture of one of history's great military machines.

Napoleon's Infantry Handbook is an essential reference guide, filled with fascinating detail on the training, tactics, equipment, service, and administration of Napoleon's infantry regiments.

Based on training manuals, regulations, and orders of the time, it details the everyday routines and practices that governed the imperial army up to the Battle of Waterloo and made it one of history's most formidable military machines. Through years of research, Terry Crowdy has amassed a huge wealth of information on every aspect of the infantryman's existence:

This remarkable book fills in the gaps left by campaign histories and even eyewitness memoirs, which often omit such details. This book doesn't merely recount what Napoleon's armies did, it explains how they did it in a world so different from our own. The result is a unique guide to the everyday life of Napoleon's infantry soldiers—as well as an outstanding reference for anyone writing about this historical period.

Napoleon's Infantry Handbook is an essential reference guide, filled with fascinating detail on the training, tactics, equipment, service, and administration of Napoleon's infantry regiments.

Based on training manuals, regulations, and orders of the time, it details the everyday routines and practices that governed the imperial army up to the Battle of Waterloo and made it one of history's most formidable military machines. Through years of research, Terry Crowdy has amassed a huge wealth of information on every aspect of the infantryman's existence:

- weapons drill and maintenance

- uniform regulations

- pay

- diet and cooking regulations

- hygiene and latrine digging

- medical care

- burial of the dead

- how to apply for leave, and more

This remarkable book fills in the gaps left by campaign histories and even eyewitness memoirs, which often omit such details. This book doesn't merely recount what Napoleon's armies did, it explains how they did it in a world so different from our own. The result is a unique guide to the everyday life of Napoleon's infantry soldiers—as well as an outstanding reference for anyone writing about this historical period.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Organisation & Personnel

Chapter 1

The Infantry Regiments

1. Introduction

The word ‘infantry’ (infanterie) had its roots in Latin and came into the French language from the Spanish infante (an infant or little servant), a reference to the foot soldiers or recruits who accompanied a mounted hombre des armas (man-at-arms). The Italians had a similar expression – fante (boy) which came to designate a fantaccino (foot soldier), a word the French corrupted into fantassin, their generic term for infantryman. The word regiment (régiment) is also believed to have found its way into French from the Spanish language at the time of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (1500–1558). The word had its origins in the Latin regimentum (administration or government) and from regere (control, or rule), and was synonymous with the word régime – in other words, it implied a body of men who were under someone’s authority. Long considered the queen of battle, like the chess piece, infantry was a flexible force which could go anywhere. Indeed, French infantry served on land, in the colonies, and even performed the role of warship garrisons, in lieu of any specialist marine force. This first chapter summarises the basic organisation of the infantry regiments between 1789 and 1815, and also outlines the roles performed by each grade within the regiment.

2. Line infantry regiments

In 1789 the French Army was composed of seventy-nine infantry regiments and twenty-three foreign infantry regiments (eleven of which were Swiss, eight ‘German’, three Irish and one from Liege). These regiments were numbered from 1 to 104, the discrepancy in number being made up by the Royal Corps of Artillery (ranked 64th), and the Provincial Troops (ranked 97th). On 1 January 1791 all the provincial regimental titles were abolished and the regiments were henceforth identified only by number. On 21 July 1791 the National Assembly decreed the 96th Infantry Regiment (formerly titled Nassau), and all those designated as German, Irish or from Liege were henceforth to be classified, recruited, paid, and uniformed just like any other French regiment. The Swiss regiments in French pay remained in service until 20 August 1792, when they were disbanded after the massacre of the Swiss Guards at the Tuileries Palace ten days previously.

On 13 July 1789 the Constituent Assembly called for the formation of a national militia called the Garde Bourgeoises. This became known as the National Guard (Garde Nationale) and played a very important part in the early years of the war. A law of 15 June 1791 called for a ‘free conscription’ of one in twenty National Guardsmen who might assemble if the state required their assistance. This was followed by a decree of 20 June 1791 which activated the National Guards in the departments bordering France’s eastern frontier. Other departments were required to provide contingents of between two and three thousand men. These volunteers were organised into battalions of ten companies, each comprising of fifty men. Before long, over seventy thousand volunteers had joined the armies protecting France’s eastern border. A decree of 12 August 1791 rationalised the composition of each battalion at 568 men in eight companies. On 14 October 1791 a law formally gave Louis XVI the power to incorporate the volunteers into the line. This did not occur and the volunteers retained their independence. From this point on the volunteers began to use the title National Volunteers (Volontaires Nationaux) to distinguish themselves from the volunteers serving in the regular army (still then recruited on a voluntary basis). They were extremely enthusiastic supporters of the new nation; their patriotism, intelligence, and generosity was often in sharp contrast to the regular army.

The law of 3 February 1792 titled the volunteers as National Guard Volunteers (Gardes Volontaires Nationaux). This law regulated their composition at two lieutenant colonels, one of whom commanded the battalion. All officer appointments were made by election. By 18 May 1792 somewhere in the region of 240,000 volunteers had been called up. After the country was declared to be ‘in danger’ on 11 July 1792 there were 257 National Guard Volunteer battalions on active service. By February 1793 there were 392 battalions of National Volunteers, plus an additional 328 volunteer corps of varying composition.

France effectively had a two-tier army: on the one hand, enthusiastic, patriotic, freedom-loving National Guard Volunteers; on the other, regular, professional soldiers whose morale was dented by the political instability around them, and irked by the better conditions enjoyed by those preferring to join the Volunteer battalions. Although the former were a symbol of everything good about the Revolution, they perhaps lacked the professionalism and sense of discipline of regular soldiers. The Volunteer battalions also lacked the supporting depots to replenish losses and to maintain the men in the field. Therefore, on 21 February 1793 the government ordered the creation of infantry half-brigades (demi-brigades) which united a single battalion of regulars with two battalions of volunteers. This was partly a political measure designed to obliterate the identity of the royal army, and partly a practical measure to create a single, coherent, manageable structure.

A half-brigade of the line of battle (demi-brigade de bataille) would be formed of a staff commanded by a brigade commander or chef de brigade (the rank of colonel was suppressed), three field battalions (each containing eight companies of fusiliers and one of grenadiers), an artillery company with six 4-pounder guns, and, in wartime, an auxiliary company which formed a depot. As it happened, the formation of the half-brigades was adjourned on 31 March 1793 due to the approaching campaign season. Their composition was further clarified in a decree of 12 August 1793, particularly in terms of the composition of the staff, and how the amalgamation would actually be accomplished. The law of 2 Frimaire II (22 November 1793) further clarified the composition of the companies (see Table 1). On 19 Nivôse II (8 January 1796) a decree was issued finally enacting the reform proposed eleven months before.

Two years later, on 18 Nivôse IV (8 January 1796) a further rationalisation took place, reducing the number of infantry corps to one hundred line half-brigades, and renumbering them by lottery. A second order ten days later raised the number to one hundred and ten. The basic structure of the half-brigade was barely changed by this second formation, consisting of three battalions and an artillery company (albeit reduced in size to three 4-pounders). Two notable changes were the addition of a second quartermaster treasurer who would remain with the depot and also the addition of a fourth battalion commander who was charged with overseeing the accounting, instruction and discipline of the corps. The auxiliary company comprised of three supernumerary officers, the craftsmen of the corps and the surplus of the men left over from the amalgamation process.

There was in fact a third amalgamation of sorts which occurred in 1799. On 10 Messidor VII (28 July 1799), the government ordered the formation of an auxiliary battalion (bataillon auxiliaire) in each department of France. Each auxiliary battalion contained ten companies (eight of fusiliers, one of chasseurs and one of grenadiers). These battalions were formed from the newly raised conscripts and were equipped locally and trained by veterans. Towards the end of the year, these auxiliary battalions were incorporated into the line, with the chasseur companies being sent to reinforce the light infantry half-brigades.

When he was First Consul, on 1 Vendémiaire XII (24 September 1803), Napoleon restored the title ‘regiment’ to the French infantry and also the title of colonel. Napoleon also reintroduced the rank of major, a senior grade which had been omitted since 1 January 1791. On 19 September 1805 each battalion of line infantry was instructed to convert its second company to one of voltigeurs, a form of light infantry skirmisher recruited from men of short stature who could never qualify for service in the grenadier companies. In many cases the implementation of this decree was interrupted somewhat by the Ulm and Austerlitz campaigns. The main change of the imperial period came on 18 February 1808 when each regiment was brought to a strength of five battalions. The first four battalions contained only six companies – four of fusiliers and one each of voltigeurs and grenadiers. The size of each company was increased, being more than twice the size of the peacetime companies formed in 1791. The fifth company formed the regimental depot and consisted of four fusilier battalions only. By adopting this measure Napoleon significantly increased the number of field battalions available to him, without having to employ significantly more sub-officers and officers. On 12 April 1811 twenty-five regiments were assigned a sixth battalion.

One of the features of Napoleon’s army was the creation of a number of ad hoc regiments. The depot companies were often collected to form provisional regiments. These might be classed as a half-brigade (demi-brigade), a provisional regiment (régiment provisoire), or a battalion of march (bataillon de marche). Often they would be returned to their parent regiment at the end of a campaign or particular mission, or incorporated into the battalions already in the field. Napoleon’s army also saw the creation of so-called grenadier divisions made from collections of elite companies removed from their parent battalions. Elite soldiers serving in the same brigade or division might also be collected to form ‘special battalions’.

After Napoleon’s first abdication in 1814 the line regiments were reorganised on 12 May 1814. The Royal Army was reduced to ninety line infantry regiments, each organised into 3 battalions of six companies, with a cadre of officers and sub-officers for a fourth battalion. This meant some regiments were renumbered or even merged. Even with prisoners of war returning to France, only six regiments actually had enough soldiers to form the third battalion. When Napoleon returned from exile in Elba in 1815, he undid the reforms of the Bourbons, restoring the renumbered regiments back to their original identities in the decree of 25 April 1815. Previous to this on 13 April 1815, he announced a provisional organisation of the infantry regiments, ordering them to form five battalions each (one depot, four field battalions). However, by the time of the Hundred Days campaign, few regiments could field more than two battalions, and these were much weaker than the 1808 equivalents (see Table 3). After Waterloo the imperial army was utterly broken up by the Bourbon government, creating new formations with no links to the army of the republic or empire.

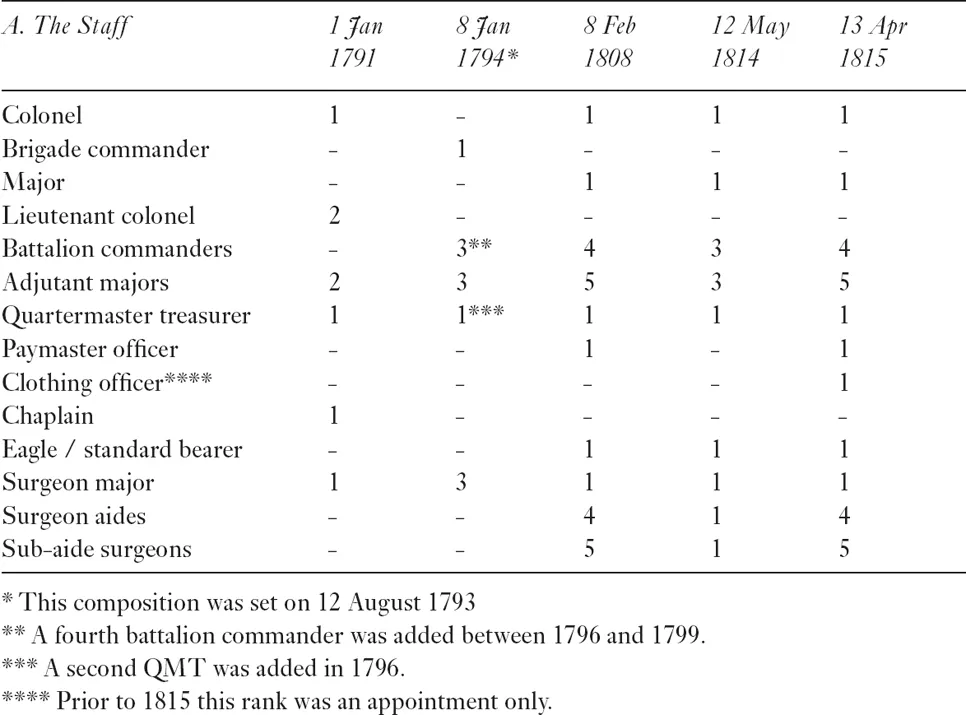

Table 3: Line infantry organisation 1791–1815.

Table 3 sets out the key changes in the effective strength of the line infantry corps over the period from 1791 to 1815. Throughout the period each regiment contained a number of staff officers who were classed as the état-major. There were also a number of soldiers and specialists who held the rank of sub-officer and were classed as the petty staff (petit état-major). Finally there were the officers and men who formed the individual companies. In addition to the positions shown in the table, each regiment would have a number of supernumerary officers (officiers à la suite), sutlers, laundresses and children. These groups and other specialist roles will be discussed later in the appropriate chapters.

A line infantry grenadier typical of the 1790s and early part of the First Empire.

3. Light infantry regiments

The wars of the 18th century saw the development of infantrymen who fought outside of the line of battle and formed part of an army’s advanced guard. France initially relied on irregulars to fulfil this function, often recruiting foreigners for the role. They also experimented with mixed ‘legions’ of light horse and infantry, or adding light infantry companies to the regiments of the line. It took until 1788 for independent battalions of foot chasseurs (huntsmen) to be formed in the manner of Frederick the Great’s jaeger corps. The purpose of these light battalions was to provide an advanced guard service to the army, scouting, protecting camps and covering retreats. Light infantry also came to play an increasingly important role on the battlefield. When originally conceived, light troops tended to be posted on the periphery during battles, guarding the flanks of the army and the camp. However, the field service regulations of 1792 assigned light infantry with four specific roles on the battlefield, namely:

1. Screen the deployment of the line infantry and artillery batteries.

2. Discover enemy dispositions.

3. Target enemy batteries and kill the gunners.

4. Pursue retreating enemy troops.

Unlike troops of the line, light infantry were to fight outside of regular troop formations and to exploit cover as it could be found.

At the outbreak of war there were fourteen battalions of light infantry; by the time of Napoleon’s first abdication in 18...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Tables

- Diagrams

- Foreword

- A Guide to Terms and Measures from Napoleonic France

- Part I: Organisation & Personnel

- Part II: Uniform, Arms & Equipment

- Part III: Recruitment & Administration

- Part IV: Discipline & Honours

- Part V: Tactical Organisation & Drill

- Part VI: Garrison Service

- Part VII: Service in the Field

- Part VIII: Health & Medical Provision

- Alphabetical Table of Articles

- Select Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Napoleon's Infantry Handbook by T. E. Crowdy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.